4. DISCUSSION

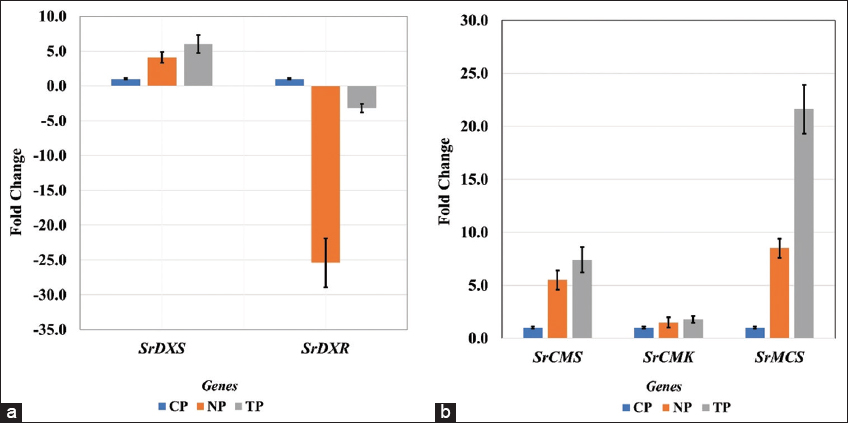

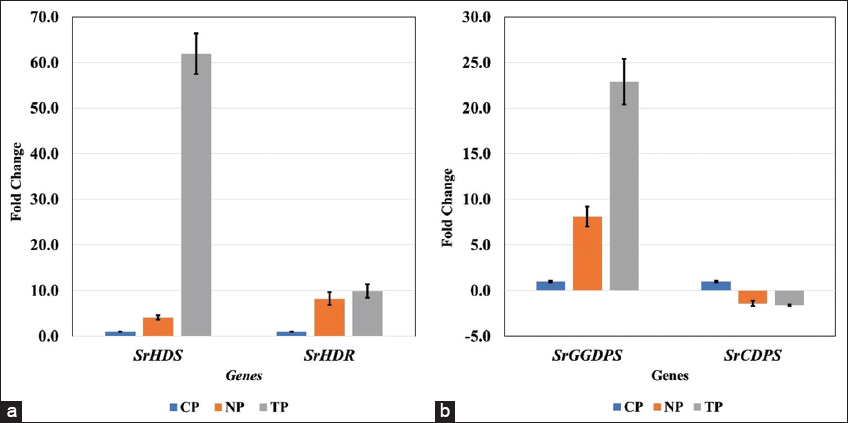

In the current study, two types of transcript accumulation patterns, up-regulation and subsequently varying rates of down-regulation, were seen in the genes of the SG biosynthesis pathway in S. rebaudiana Bertoni, both in transformed and non-transformed lines. The highest transcript levels among the up-regulated genes were found in the leaves of the TPs, indicating that, out of the 15 pathway genes investigated in this study, R. rhizogenes-infected plants had superior transcript level, in general. The present findings are quite similar to the findings of Sarmiento-López, in 2020; Libik-Konieczny et al., in 2020, and Sanchéz-Cordova et al., in 2019 [23-25]. However, specifically, 13 genes were upregulated, and two of them were downregulated in the current study.

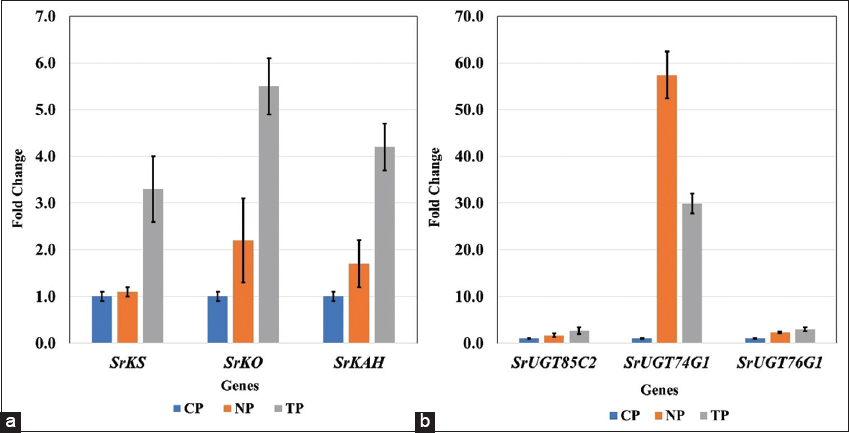

In our findings, higher transcript abundance (i.e., up-regulation) in three genes, SrKS (KS), SrKO (KO), and SrKAH (KAH) were recorded in TP and NP as compared to CP, which showed enhanced SGs content in leaves, corroborated with the earlier finding in Stevia by Zheng et al., 2019, and Nasrullah et al., 2023 [26,27]. The genes SrKO and SrUGT74G1 show high expression, leading to an increase in Stevioside level. This finding correlates with studies by Nasrullah et al., 2023 in S. rebaudiana, demonstrating their significant role in enhancing SG content [28].

In the present research, all NP and TP lines were propagated using the same combination of plant hormones in MS media and maintained under the same growth conditions [15], however, a higher SrUGT74G1 expression level was noted in NP when compared with transformed lines (TP). Expression increase of SrUGT74G1 in NP could be due to metabolic reprogramming during micropropagation stress. The lack of comparable expression in TP, even with the same culture conditions, may indicate that in the secondary metabolism of plants, the feedback regulation mechanisms responsive to the complete metabolites tend to inhibit the expression of biosynthetic pathways. For instance, Gachon et al., in 2005 and Tiwari et al., in 2016, discuss how glycosylation, mediated by glycosyltransferases, plays a crucial role in regulating hormone homeostasis and secondary metabolite biosynthesis [28,29].

In TP lines, higher flux through the steviol biosynthetic pathway might activate such feedback loops, leading to the downregulation of SrUGT74G1. Conversely, NP plants, with comparatively lower precursor flux, may not trigger these feedback mechanisms, resulting in higher expression levels of SrUGT74G. Another reason might be the choice of explants [30]. For the NP plants, nodal explants were used for direct shoot regeneration while, in case of TP plants, micro-shoots with hairy roots were used as explants for TP regeneration [15]. In addition, post-transcriptional regulation, including mechanisms mediated by microRNAs (miRNAs), can influence gene expression levels. Kajla et al, in 2023 highlight the role of miRNAs in fine-tuning the expression of genes involved in secondary metabolite biosynthesis. Such regulatory processes can lead to variations in gene expression independent of genetic transformation [31].

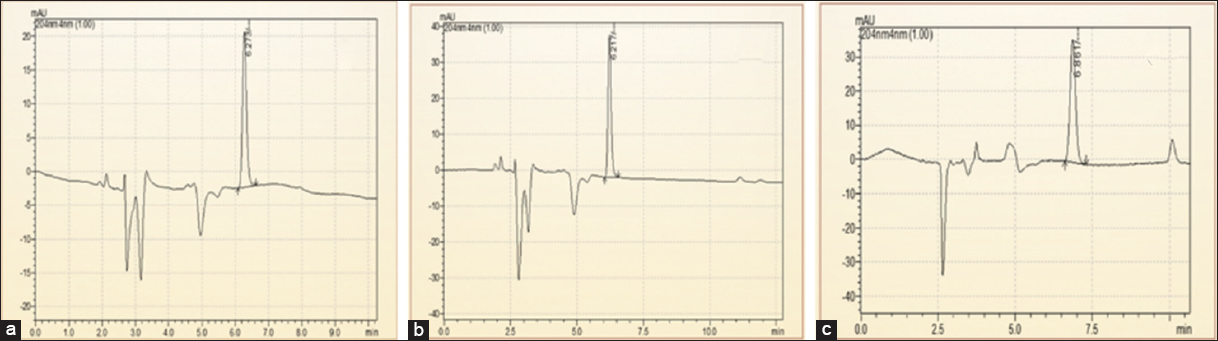

In the present study, two genes, SrDXS and SrCDPS indicated a downregulation, and despite that, in in vitro generated plants, stevioside levels were still high, as confirmed by HPLC analysis. This could be achievable due to such genes being part of a complex regulatory network in the SG pathway, which may involve a feedback mechanism, post-transcriptional regulation, and compensatory upregulation of other genes to sustain or even elevate overall SG production. The increased flux through the SG pathway in in vitro plantlets may trigger feedback regulation mechanisms. These mechanisms, which respond to the total metabolites, prefer to suppress the expression of biosynthetic pathways. On the other hand, in vivo plants, with relatively reduced precursor flux, might not activate these feedback mechanisms, resulting in varying expression levels. Moreover, the upregulation of major downstream UGT genes, specifically SrUGT76G1, could counteract the downregulation of upstream genes such as SrCDPS and SrDXR, resulting in net increase in SG accumulation. Similar trends have been reported in Stevia transformation studies, where enhanced glycosylation contributed to higher SG yields despite variations in early pathway gene expression [32,33]. Lower expression of these genes can also act as positive regulators of the pathway. The correlation between gene expression and SG quantification highlights the complex regulation of the biosynthetic pathway. While some genes exhibit downregulation, the overall metabolic flux toward stevioside biosynthesis appears to be driven by the enhanced expression of key glycosyltransferases. This underscores the potential for targeted genetic modifications to optimize SG production in Stevia [34,35].

HPLC data of the current research showed that transformed Stevia plants had higher stevioside content compared to micropropagated plants (NP), which in turn accumulated more stevioside than the in vivo, grown CP. This trend largely coincides with the gene expression data obtained through real-time PCR analysis in the current study. Similar findings regarding enhanced SG accumulation in R. rhizogenes-mediated transformed S. rebaudiana plantlets were reported by Sánchez-Córdova and co-workers in (2019) [25]. The rise in stevioside content in NP as compared to the CPs might be attributed to tissue culture-induced metabolic reprogramming [36], where the controlled in vitro environment and synchronized developmental stage of regenerated plantlets can enhance secondary metabolite biosynthesis.

The present work mainly focused on HPLC analysis to quantify stevioside, one of the most predominant and important SGs found in S. rebaudiana. Stevioside is a central intermediate in the biosynthetic pathway and is frequently used as a reliable metabolic marker owing to its high accumulation in the leaf tissues. If other glycosides such as rebaudioside A were to be measured, a better picture of the metabolite spectrum would have emerged; however, the targeted analysis of stevioside alone provides a strong and representative estimate of the biosynthetic activity. This holds true for the main objective of correlating gene expression patterns with the core output of the SG biosynthesis pathway. In addition, focusing on stevioside has allowed for an accurate assessment of the impact of transformation and regeneration conditions on its accumulation.

REFERENCES

1. Sharma S, Gupta S, Kumari D, Kothari SL, Jain R, Kachhwaha S. Exploring plant tissue culture and steviol glycosides production in Stevia rebaudiana (Bert.) Bertoni:A review. Agriculture. 2023;13(2):475.[CrossRef]

2. Hajihashemi S, Geuns JM, Ehsanpour AA. Gene transcription of steviol glycoside biosynthesis in Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni under polyethylene glycol, paclobutrazol and gibberellic acid treatments in vitro. Acta Physiol Plantarum. 2013;35:2009-14.[CrossRef]

3. Brandle JE, Telmer PG. Steviol glycoside biosynthesis. Phytochemistry. 2007;68(14):1855-63.[CrossRef]

4. Thakur K, Ashrita, Sood A, Kumar P, Kumar D, Warghat AR. Steviol glycoside accumulation and expression profiling of biosynthetic pathway genes in elicited in vitro cultures of Stevia rebaudiana. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 2021;57:214-24.[CrossRef]

5. Zhou X, Gong M, Lv X, Liu Y, Li J, Du G, et al. Metabolic engineering for the synthesis of steviol glycosides:Current status and future prospects. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2021;105(13):5367-81.[CrossRef]

6. Ceunen S, Werbrouck S, Geuns JM. Stimulation of steviol glycoside accumulation in Stevia rebaudiana by red LED light. J Plant Physiol. 2012;169(7):749-52.[CrossRef]

7. Eslami-Firouzabadi A, Karimi M, Abbasi-Surki A, Shafeinia A, Derikvand-Moghadam F. Optimising the rate and stages of application of nitrogen fertiliser for stevia under greenhouse conditions. South African Journal of Plant and Soil 2023;40:58-63.[CrossRef]

8. Olas B. Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni and its secondary metabolites:Their effects on cardiovascular risk factors. Nutrition. 2022;99:111655.[CrossRef]

9. Abdel-Aal RA, Abdel-Rahman MS, Al Bayoumi S, Ali LA. Effect of stevia aqueous extract on the antidiabetic activity of saxagliptin in diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021;265:113188.[CrossRef]

10. Bugliani M, Tavarini S, Grano F, Tondi S, Lacerenza S, Giusti L, et al. Protective effects of Stevia rebaudiana extracts on beta cells in lipotoxic conditions. Acta Diabetol. 2022;59:113-126.[CrossRef]

11. Peteliuk V, Rybchuk L, Bayliak M, Storey KB, Lushchak O. Natural sweetener Stevia rebaudiana:Functionalities, health benefits and potential risks. EXCLI J. 2021;20:1412.[CrossRef]

12. Abdullah S, Mohamad Fauzi NY, Khalid AK, Osman M. Effect of gamma rays on seed germination, survival rate and morphology of Stevia rebaudiana hybrid. Malays J Fundam Appl Sci. 2021;17(5):543-9.[CrossRef]

13. Álvarez-Robles MJ, López-Orenes A, Ferrer MA, Calderón AA. Methanol elicits the accumulation of bioactive steviol glycosides and phenolics in Stevia rebaudiana shoot cultures. Ind Crops Prod. 2016;87:273-9.[CrossRef]

14. Kahrizi D, Ghaheri M, Yari Z, Yari K, Bahraminejad S. Investigation of different concentrations of MS media effects on gene expression and steviol glycosides accumulation in Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni. Cell Mol Biol. 2018;64(2):23-7.[CrossRef]

15. Singh P, Labade D, Chote M, Deshmukh P, Panchal B, Deshpande J, et al. Efficient regeneration of Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni transformants through hairy root culture technique. J Appl Bot Food Qual. 2025;98:22-8. [CrossRef]

16. Pan H, Xiao L, Tang K, Xia H, Li Y, Jia H, et al. Screening UDP-glycosyltransferases for effectively transforming stevia glycosides:Enzymatic synthesis of glucosylated derivatives of rubusoside. J Agric Food Chem. 2022;70(48):15178-88.[CrossRef]

17. Yu J, Tao Y, Pan H, Lin L, Sun J, Ma R, et al. Mutation of Stevia glycosyltransferase UGT76G1 for efficient biotransformation of rebaudioside E into rebaudioside M. J Funct Foods. 2022;92:105033.[CrossRef]

18. Ghaheri M, Kahrizi D, Bahrami G, Mohammadi-Motlagh HR. Study of gene expression and steviol glycosides accumulation in Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni under various mannitol concentrations. Mol Biol Rep. 2019;46(1):7-16.[CrossRef]

19. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2- ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402-8.[CrossRef]

20. Herath V, Gayral M, Adhikari N, Miller R, Verchot J. Genome-wide identification and characterization of Solanum tuberosum BiP genes reveal the role of the promoter architecture in BiP gene diversity. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):11327.[CrossRef]

21. Phule AS, Barbadikar KM, Maganti SM, Seguttuvel P, Subrahmanyam D, Babu MP, et al. RNA-seq reveals the involvement of key genes for aerobic adaptation in rice. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):5235.[CrossRef]

22. Ye J, Jin CF, Li N, Liu MH, Fei ZX, Dong LZ, et al. Selection of suitable reference genes for qRT-PCR normalisation under different experimental conditions in Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):15043.[CrossRef]

23. Sarmiento-López LG, López-Meyer M, Sepúlveda-Jiménez G, Cárdenas L, Rodríguez-Monroy M. Photosynthetic performance and stevioside concentration are improved by the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in Stevia rebaudiana under different phosphate concentrations. PeerJ. 2020;8:10173.[CrossRef]

24. Libik-Konieczny M, Michalec-Warzecha ?, Dziurka M, Zastawny O, Konieczny R, Rozp?dek P, et al. Steviol glycosides profile in Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni hairy roots cultured under oxidative stress-inducing conditions. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;104:5929-41.[CrossRef]

25. Sanchéz-Cordova ÁD, Capataz-Tafur J, Barrera-Figueroa BE, López-Torres A, Sanchez-Ocampo PM, García-López E, et al. Rhizobium rhizogenes-mediated transformation enhances steviol glycosides production and growth in Stevia rebaudiana plantlets. Sugar Tech. 2019;21(3):398-406.[CrossRef]

26. Zheng J, Zhuang Y, Mao HZ, Jang IC. Overexpression of SrDXS1and SrKAH enhances steviol glycosides content in transgenic Stevia plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19:1-6.[CrossRef]

27. Nasrullah N, Ahmad J, Saifi M, Shah IG, Nissar U, Quadri SN, et al. Enhancement of diterpenoid steviol glycosides by co-overexpressing SrKO and SrUGT76G1 genes in Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni. PLoS One. 2023;18(2):0260085.[CrossRef]

28. Gachon CM, Langlois-Meurinne M, Saindrenan P. Plant secondary metabolism glycosyltransferases:The emerging functional analysis. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10(11):542-9.[CrossRef]

29. Tiwari P, Sangwan RS, Sangwan NS. Plant secondary metabolism linked glycosyltransferases:An update on expanding knowledge and scopes. Biotechnol Adv. 2016;34(5):714-39.[CrossRef]

30. Bednarek PT, Or?owska R. Plant tissue culture environment as a switch-key of (EPI) genetic changes. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2020;140(2):245-57.[CrossRef]

31. Kajla M, Roy A, Singh IK, Singh A. Regulation of the regulators:Transcription factors controlling biosynthesis of plant secondary metabolites during biotic stresses and their regulation by miRNAs. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1126567.[CrossRef]

32. Kim MJ, Zheng J, Liao MH, Jang IC. Overexpression of Sr UGT 76G1 in Stevia alters major steviol glycosides composition towards improved quality. Plant Biotechnol J. 2019;17(6):1037-47.[CrossRef]

33. Abdelsalam NR, Botros WA, Khaled AE, Ghonema MA, Hussein SG, Ali HM, et al. Comparison of uridine diphosphate-glycosyltransferase UGT76G1 genes from some varieties of Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):8559.[CrossRef]

34. Singh S, Murmu S, Das AB, Haider ZA, Banerjee M. Establishment of root-to-root culture and evaluation of phytochemicals in Rhizobium rhizogenes transformed roots of Stevia rebaudiana. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2017;6(6S):49-54.

35. Bayraktar M, Naziri E, Karabey F, Akgun IH, Bedir E, Röck-Okuyucu B, et al. Enhancement of stevioside production by using biotechnological approach in in vitro culture of Stevia rebaudiana. Int J Secondary Metab. 2018;5(4):362-74.[CrossRef]

36. Fazili MA, Bashir I, Ahmad M, Yaqoob U, Geelani SN. In vitro strategies for the enhancement of secondary metabolite production in plants:A review. Bull Natl Res Centre. 2022;46(1):35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-022-00717-z[CrossRef]