4. DISCUSSION

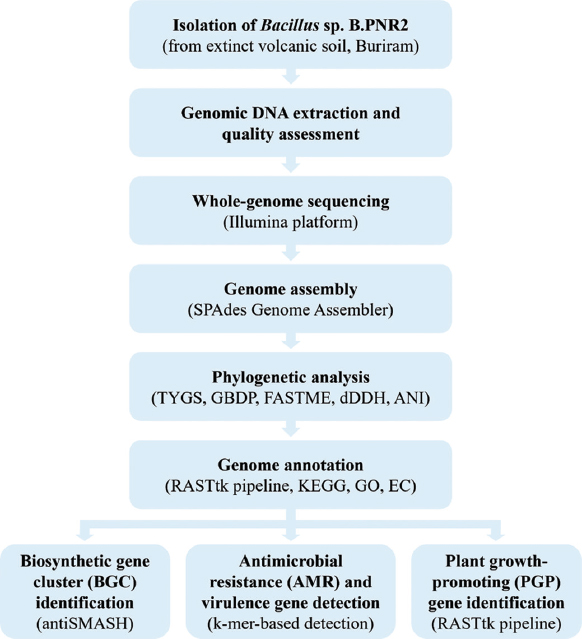

The comprehensive genomic and functional characterization of Bacillus sp. B.PNR2 underscores its exceptional potential as a biocontrol agent and a valuable bioresource for natural product discovery. Isolated from nutrient-poor, geothermally influenced volcanic soil in Northeastern Thailand, B.PNR2 appears well adapted to natural soil environments, as evidenced by its extensive genetic repertoire related to stress tolerance, secondary metabolite biosynthesis, and nutrient acquisition [17]. These adaptive features highlight its ecological competitiveness and suitability for application in challenging agricultural systems [44,45]. In this study, phylogenomic analysis identified B.PNR2 as a strain of B. stercoris, supported by high dDDH and ANI values [27,46,47]. The distinct composition of its BGCs and AMR genes further supports this classification and enhances its value as a genomic resource.

In this study, the genome annotation revealed a complex metabolic framework comprising 4,283 protein-CDSs, the majority of which were functionally characterized. Subsystem classification indicated a high abundance of genes related to metabolism, stress response, energy production, and virulence. This genetic architecture implies not only resilience in harsh soil environments but also a capacity for dynamic interactions both antagonistic and symbiotic with other soil microorganisms. A notable feature of the B.PNR2 genome is the presence of 13 BGCs identified by antiSMASH, including clusters encoding well-characterized antimicrobial compounds such as fengycin, surfactin, bacilysin, bacillaene, subtilosin A, and bacillibactin. These metabolites form a multifunctional arsenal that acts through membrane disruption, iron chelation, enzyme inhibition, and immune modulation. The co-occurrence of fengycin and surfactin clusters is particularly significant, given their synergistic antifungal activities – a hallmark of effective Bacillus-mediated biocontrol. Our findings align with reports that Bacillus species commonly combine antimicrobial metabolite production with PGP traits. Prior studies have highlighted lineage-specific adaptations and metabolite profiles supporting biocontrol activity [17,48], which is consistent with the BGC repertoire and PGP genes observed in B.PNR2.

Intriguingly, genome mining revealed several BGCs with low homology to known reference clusters, including those potentially associated with zwittermicin A-like compounds, plipastatin, and carbapenem-like metabolites. Zwittermicin A (ZmA), a linear aminopolyol antibiotic originally isolated from B. cereus UW85, has demonstrated broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, including antiprotist, antibacterial (against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria), and antifungal properties [49-52]. ZmA also synergistically enhances the insecticidal activity of Bacillus thuringiensis toxins [53]. Likewise, plipastatin, a lipopeptide produced by B. subtilis, is recognized for its potent antifungal activity and holds promise as a biocontrol agent to replace synthetic fungicides in agricultural applications [54]. Carbapenems, a class of β-lactam antibiotics, are considered critically important due to their broad-spectrum efficacy and potency against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [55]. The presence of cryptic BGCs with low similarity to known clusters suggests the potential for structurally novel compounds with unique modes of action, especially a promising avenue in the face of rising AMR. Further functional characterization of these clusters will be essential to unlocking new microbial natural products.

In terms of environmental adaptability, Bacillus sp. B.PNR2 possesses a diverse repertoire of AMR genes and transporter systems. A total of 41 AMR genes were identified, representing a range of resistance mechanisms, including antibiotic-inactivating enzymes, target site modifications, protective proteins, and multidrug efflux systems, features that likely confer a competitive advantage in microbially rich soil environments. In addition, the presence of 322 transporter genes suggests enhanced capabilities for nutrient acquisition and detoxification, contributing to the strain’s fitness under dynamic environmental conditions. Nevertheless, the presence of 41 AMR genes and several virulence-related factors warrants careful biosafety consideration before any field application. These elements may influence microbial community interactions and horizontal gene transfer in soil ecosystems; therefore, risk assessment and appropriate containment strategies will be essential in future agricultural deployment of B.PNR2. This finding aligns with the study by Deng et al. [56], who employed multi-omics analyses to investigate Bacillus mutant strains under environmental stress. Their results revealed coordinated changes at the genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic levels. Despite harboring different genetic mutations, the mutants exhibited similar proteomic responses. Key metabolic pathways including the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas glycolytic pathway, the pentose phosphate pathway, and purine biosynthesis, were significantly modulated to regulate inosine production. In addition, stress-responsive proteins involved in translation, molecular chaperoning, DNA repair, oxidative stress defense, and cell envelope stability were upregulated, enhancing the mutants’ survival under extreme conditions such as those found in near-space environments. Similarly, Valencia-Marín et al. [57] reported that Bacillus species can survive in saline-stressed soils through multiple mechanisms, including the production of osmoprotectant compounds, antioxidant enzymes, exopolysaccharides, and alterations in membrane lipid composition. Additional survival strategies such as sporulation and entry into a reduced metabolic state were also noted, particularly in the context of functional interactions within the rhizosphere.

Beyond antimicrobial potential, Bacillus sp. B.PNR2 also harbors PGP traits, including IAA biosynthesis, phosphate solubilization, siderophore production, and nitrogen metabolism genes, consistent with phenotypes reported previously [5,22]. Taken together with the diversity of its BGCs, these features support a dual potential in crop growth promotion and pathogen suppression.

The genomic insights obtained in this study have direct implications for biotechnological applications. In agriculture, B. stercoris B.PNR2 could be developed into biofertilizer formulations, leveraging its IAA biosynthesis, phosphate solubilization, siderophore production, and nitrogen metabolism genes to enhance crop growth and nutrient use efficiency. As a biocontrol agent, the strain possesses diverse antimicrobial BGCs, including those encoding fengycin, surfactin, bacilysin, and bacillibactin, which provide broad-spectrum suppression of phytopathogens and can reduce dependence on chemical pesticides. In environmental biotechnology, its stress tolerance and AMR gene repertoire suggest resilience in contaminated or degraded soils, supporting potential use in soil remediation or reclamation programs. Furthermore, the presence of cryptic BGCs with low similarity to known clusters represents a valuable genomic resource that may yield structurally novel bioactive compounds. However, functional validation will be necessary before specific pharmaceutical applications can be established.

Taken together, these findings suggest that Bacillus sp. B.PNR2 holds promise as a candidate for integrated pest and nutrient management in sustainable agriculture. The genomic prediction of low-similarity BGCs also highlights its potential as a source for future antimicrobial discovery, pending experimental confirmation. Future research should prioritize functional validation of cryptic BGCs through transcriptomics, heterologous expression, and metabolite isolation. At the same time, greenhouse and field trials will be essential to confirm the biocontrol and PGP efficacy of B.PNR2 under real-world agricultural conditions. These combined efforts will advance microbial-based biotechnologies and contribute meaningfully to global initiatives in sustainable agriculture and antibiotic innovation.

REFERENCES

1. Damalas CA, Koutroubas SD. Current status and recent developments in biopesticide use. Agriculture. 2018;8(1):13.[CrossRef]

2. Thomine E, Mumford J, Rusch A, Desneux N. Using crop diversity to lower pesticide use:Socio-ecological approaches. Sci Total Environ. 2022;804:150156.[CrossRef]

3. Chaudhary R, Nawaz A, Khattak Z, Butt MA, Fouillaud M, DufosséL, et al. Microbial bio-control agents:A comprehensive analysis on sustainable pest management in agriculture. J Agric Food Res. 2024;18:101421.[CrossRef]

4. Tyagi A, Lama Tamang T, Kashtoh H, Mir RA, Mir ZA, Manzoor S,et al.Areview on biocontrol agents as sustainable approach for crop disease management:Applications, production, and future perspectives. Horticulturae. 2024;10(8):805.[CrossRef]

5. Pengproh R, Thanyasiriwat T, Sangdee K, Saengprajak J, Kawicha P, Sangdee A. Evaluation and genome mining of Bacillus stercoris isolate B. PNR1 as potential agent for fusarium wilt control and growth promotion of tomato. Plant Pathol J. 2023;39(5):430.[CrossRef]

6. Rios-Reyes A, Gonzalez-Lozano K, Cabral-Miramontes J, Hernandez-Gonzalez J, Rios-Sosa A, Alvarez-Gutierrez P, et al. Exploration of plant and microbial life at “El Chichonal“volcano with a sustainable agriculture prospection. Microb Ecol. 2025;88(1):67.[CrossRef]

7. Miljakovic D, Marinkovic J, Baleševic-Tubic S. The significance of Bacillusspp. disease suppression and growth promotion of field and vegetable crops. Microorganisms. 2020;8(7):1037.[CrossRef]

8. Borriss R. Use of plant-associated Bacillusstrains as biofertilizers and biocontrol agents in agriculture. In:Maheshwari DK, editor. Bacteria in Agrobiology:Plant Growth Responses. Berlin, Heidelberg:Springer Berlin Heidelberg;2011. 41-76.[CrossRef]

9. Beneduzi A, Ambrosini A, Passaglia LM. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR):Their potential as antagonists and biocontrol agents. Genet Mol Biol. 2012;35(4 (suppl)):1044-51.[CrossRef]

10. Fatima A, Abbas M, Nawaz S, Rehman Y, ur Rehman S, Sajid I. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) and genome mining of Streptomycessp. AFD10 for antibiotics and bioactive secondary metabolites biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). Gene Rep. 2024;37:102050.[CrossRef]

11. Palazzotto E, Weber T. Omics and multi-omics approaches to study the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites in microorganisms. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2018;45:109-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2018.03.004[CrossRef]

12. Zhang Z, Yin L, Li X, Zhang C, Zou H, Liu C, et al. Analyses of the complete genome sequence of the strain Bacillus pumilusZB201701 isolated from rhizosphere soil of maize under drought and salt stress. Microbes Environ. 2019;34(3):310-5.[CrossRef]

13. Li Z, Song C, Yi Y, Kuipers OP. Characterization of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria from perennial ryegrass and genome mining of novel antimicrobial gene clusters. BMC Genomics. 2020;21(1):157.[CrossRef]

14. Iqbal S, Vollmers J, Janjua HA. Genome mining and comparative genome analysis revealed niche-specific genome expansion in antibacterial Bacillus pumilus strain SF-4. Genes. 2021;12(7):1060.[CrossRef]

15. Ribeiro ID, Bach E, da Silva Moreira F, Müller AR, Rangel CP,Wilhelm CM, et al. Antifungal potential against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) Bary and plant growth promoting abilities of Bacillus isolates from canola (Brassica napus L.) roots. Microbiol Res. 2021;248:126754.[CrossRef]

16. Biessy A, Filion M. Complete genome sequence of Bacillus pumilus LBUM494, a plant-beneficial strain isolated from the rhizosphere of a strawberry plant. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2024;13(10):0082524.[CrossRef]

17. Dushku E, Kotzamanidis C, Kargas A, Maria-Eleni FL, Giantzi V, Krystallidou E, et al. Unveiling the genetic basis of biochemical pathways of plant growth promotion in Bacillus pumilus and the first genomic insights into B. as a biostimulant. Curr Res Microb Sci. 2025:100419.[CrossRef]

18. Chen J, Xu D, Xiao Q, Zheng Y, Liu H, Li X, et al. Responses of soil microbial diversity, network complexity and multifunctionality to environments changes in volcanic ecosystems. J Environ Chem Eng. 2024;12(5):113334.[CrossRef]

19. Fagorzi C, Del Duca S, Venturi S, Chiellini C, Bacci G, Fani R, et al. Bacterial communities from extreme environments:Vulcano Island. Diversity. 2019;11(8):140.[CrossRef]

20. Li SJ, Hua ZS, Huang LN, Li J, Shi SH, Chen LX, et al. Microbial communities evolve faster in extreme environments. Sci Rep. 2014;4(1):6205.[CrossRef]

21. Verma P, Yadav AN, Kumar V, Singh DP, Saxena AK. Beneficial plant-microbes interactions:biodiversity of microbes from diverse extreme environments and its impact for crop improvement. In:Plant-Microbe Interactions in Agro-Ecological Perspectives:Microbial Interactions and Agro-Ecological Impacts. Vol. 2. Springer;2017. 543-80.[CrossRef]

22. Somtrakoon K, Prasertsom P, Sangdee A, Pengproh R, Chouychai W. Potential of Bacillus stercoris B. PNR2 to stimulate growth of rice and waxy corn under atrazine-contaminated soil. J Arid Agric. 2024;10:20-7.[CrossRef]

23. Sangdee A, Plaikan S, Chayapat T, Kawicha P, Somtrakoon K. Plant growth-promoting gene expression in Bacillus stercoris under atrazine contamination and their ability to stimulate growth of mung bean seedlings. N Z J Crop Hortic Sci. 2025;53:2165-87.[CrossRef]

24. Boottanun P, Potisap C, Hurdle JG, Sermswan RW. Secondary metabolites from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens isolated from soil can kill Burkholderia pseudomallei. AMB Express. 2017;7(1):16.[CrossRef]

25. Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, et al. SPAdes:a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19(5):455-77.[CrossRef]

26. Meier-Kolthoff JP, Göker M. TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2182.[CrossRef]

27. Meier-Kolthoff JP, Auch AF, Klenk HP, Göker M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14(1):60.[CrossRef]

28. Meier-Kolthoff JP, Carbasse JS, Peinado-Olarte RL, Göker M. TYGS and LPSN:A database tandem for fast and reliable genome-based classification and nomenclature of prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(D1):D801-7.[CrossRef]

29. Lefort V, Desper R, Gascuel O. FastME 2.0:A comprehensive, accurate, and fast distance-based phylogeny inference program. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32(10):2798-800.[CrossRef]

30. Farris JS. Estimating phylogenetic trees from distance matrices. Am Nat. 1972;106(951):645-68.[CrossRef]

31. Kreft L, Botzki A, Coppens F, Vandepoele K, Van Bel M. PhyD3:A phylogenetic tree viewer with extended phyloXML support for functional genomics data visualization. Bioinformatics. 2017;33(18):2946-7.[CrossRef]

32. Richter M, Rosselló-Móra R, Oliver Glöckner F, Peplies J. JSpeciesWS:A web server for prokaryotic species circumscription based on pairwise genome comparison. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(6):929-31.[CrossRef]

33. Brettin T, Davis JJ, Disz T, Edwards RA, Gerdes S, Olsen GJ, et al. RASTtk:A modular and extensible implementation of the RAST algorithm for building custom annotation pipelines and annotating batches of genomes. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):8365.[CrossRef]

34. Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG:Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):27-30.[CrossRef]

35. Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, et al. Gene ontology:Tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):25-9.[CrossRef]

36. Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry 1978:Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry on the Nomenclature and Classification of Enzymes. United States:Academic Press;1979.

37. Schomburg I, Chang A, Ebeling C, Gremse M, Heldt C, Huhn G, et al. BRENDA, the enzyme database:Updates and major new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(suppl_1):D431-3.[CrossRef]

38. Antonopoulos DA, Assaf R, Aziz RK, Brettin T, Bun C, Conrad N,et al. PATRIC as a unique resource for studying antimicrobial resistance. Brief Bioinform. 2019;20(4):1094-102.[CrossRef]

39. Blin K, Shaw S, Vader L, Szenei J, Reitz ZL, Augustijn HE, et al. SMASH 8.0:extended gene cluster detection capabilities and analyses of chemistry, enzymology, and regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025;53:gkaf334.[CrossRef]

40. Alcock BP, Huynh W, Chalil R, Smith KW, Raphenya AR, Wlodarski MA, et al. CARD 2023:Expanded curation, support for machine learning, and resistome prediction at the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(D1):D690-9.[CrossRef]

41. Florensa AF, Kaas RS, Clausen P, Aytan-Aktug D, Aarestrup FM. ResFinder - an open online resource for identification of antimicrobial resistance genes in next-generation sequencing data and prediction of phenotypes from genotypes. Microb Genom. 2022;8(1):000748.[CrossRef]

42. Mao C, Abraham D, Wattam AR, Wilson MJ, Shukla M, Yoo HS, et al. Curation, integration and visualization of bacterial virulence factors in PATRIC. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(2):252-8.[CrossRef]

43. The UniProt Consortium. UniProt:The universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;45(D1):D158-69.[CrossRef]

44. Saleem MH, Noreen S, Ishaq I, Saleem A, Khan KA, Ercisli S, et al. Omics technologies:Unraveling abiotic stress tolerance mechanisms for sustainable crop improvement. J Plant Growth Regul. 2025;44:4165-87.[CrossRef]

45. Taheri P, Puopolo G, Santoyo G. Plant growth-promoting microorganisms:New insights and the way forward. Microbiol Res. 2025;297:128168.[CrossRef]

46. Chun J, Oren A, Ventosa A, Christensen H, Arahal DR, da Costa MS, et al. Proposed minimal standards for the use of genome data for the taxonomy of prokaryotes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2018;68(1):461-6[CrossRef]

47. Richter M, Rosselló-Móra R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106(45):19126-31.[CrossRef]

48. Xiang L, Zhou Z, Wang X, Jiang G, Cheng J, Hu Y,et al. Surfactin, bacillibactin and bacilysin are the main antibacterial substances of Bacillus subtilisJSHY-K3 that inhibited the growth of VpAHPND (the main pathogen of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease in shrimp). Aquac Rep. 2025;42:102745.[CrossRef]

49. Silo-Suh LA, Lethbridge BJ, Raffel SJ, He H, Clardy J, Handelsman J. Biological activities of two fungistatic antibiotics produced by Bacillus cereus UW85. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60(6):2023-30.[CrossRef]

50. Silo-Suh LA, Stabb EV, Raffel SJ, Handelsman J. Target range of zwittermicin A, an aminopolyol antibiotic from Bacillus cereus. Curr Microbiol. 1998;37(1):6-11.[CrossRef]

51. Rogers EW, Dalisay DS, Molinski TF. (+)-Zwittermicin A:assignment of its complete configuration by total synthesis of the enantiomer and implication of D-serine in its biosynthesis. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47(42):8086-9.[CrossRef]

52. Kevany BM, Rasko DA, Thomas MG. Characterization of the complete zwittermicin A biosynthesis gene cluster from Bacillus cereus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75(4):1144-55.[CrossRef]

53. Broderick NA, Goodman RM, Handelsman J, Raffa KF. Effect of host diet and insect source on synergy of gypsy moth (Lepidoptera:Lymantriidae) Mortality to Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstakiby Zwittermicin A. Environ Entomol. 2003;32(2):387-91.[CrossRef]

54. Vahidinasab M, Lilge L, Reinfurt A, Pfannstiel J, Henkel M, Morabbi Heravi K, et al. Construction and description of a constitutive plipastatin mono-producing Bacillus subtilis. Microb Cell Fact. 2020;19(1):205.[CrossRef]

55. Papp-Wallace KM, Endimiani A, Taracila MA, Bonomo RA. Carbapenems: Past, present, and future. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(11):4943-60.[CrossRef]

56. Deng A, Wang T, Wang J, Li L, Wang X, Liu L, et al. Adaptive mechanisms of Bacillusto near space extreme environments. Sci Total Environ. 2023;886:163952.[CrossRef]

57. Valencia-Marin MF, Chávez-Avila S, Guzmán-Guzmán P, del Carmen Orozco-Mosqueda M, de Los Santos-Villalobos S, Glick BR, et al. Survival strategies of Bacillusspp. saline soils:Key factors to promote plant growth and health. Biotechnol Adv. 2024;70:108303.[CrossRef]

58. Sur S, Romo TD, Grossfield A. Selectivity and mechanism of fengycin, an antimicrobial lipopeptide, from molecular dynamics. J Phys Chem B. 2018;122(8):2219-26.[CrossRef]

59. Patel PS, Huang S, Fisher S, Pirnik D, Aklonis C, Dean L, et al. Bacillaene, a novel inhibitor of procaryotic protein synthesis produced by Bacillus subtilis:Production, taxonomy, isolation, physico-chemical characterization and biological activity. J Antibiot. 1995;48(9):997-1003.[CrossRef]

60. Shelburne CE, An FY, Dholpe V, Ramamoorthy A, Lopatin DE, Lantz MS. The spectrum of antimicrobial activity of the bacteriocin subtilosin A. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59(2):297-300.[CrossRef]

61. Chakraborty K, Kizhakkekalam VK, Joy M, Chakraborty RD. Bacillibactin class of siderophore antibiotics from a marine symbiotic Bacillusas promising antibacterial agents. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2022;106(1):329-40.[CrossRef]

62. Tichy E, Luisi B, Salmond G. Crystal structure of the carbapenem intrinsic resistance protein CarG. J Mol Biol. 2014;426(9):1958-70.[CrossRef]

63. Das P, Mukherjee S, Sen R. Antimicrobial potential of a lipopeptide biosurfactant derived from a marine Bacillus circulans. J Appl Microbiol. 2008;104(6):1675-84.[CrossRef]

64. Zhen C, Ge XF, Lu YT, Liu WZ. Chemical structure, properties and potential applications of surfactin, as well as advanced strategies for improving its microbial production. AIMS Microbiol. 2023;9(2):195.[CrossRef]