1. INTRODUCTION

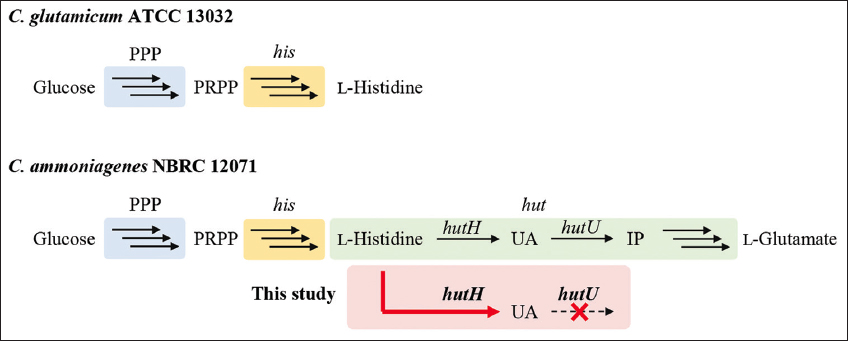

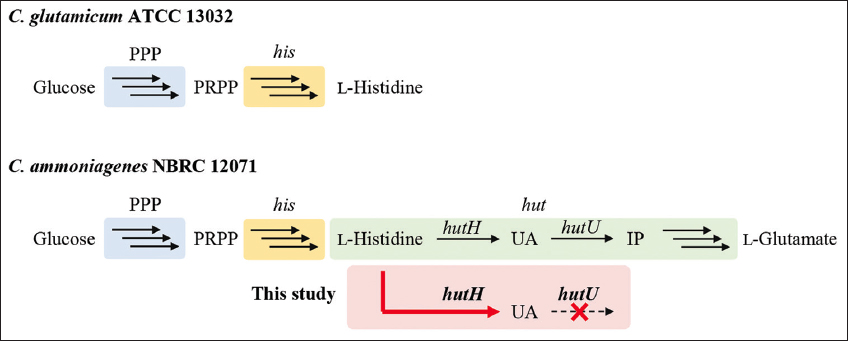

Metabolites exhibit diverse chemical structures and bioactivities. To utilize these metabolites industrially, a production system should be developed [1,2]. Urocanic acid (UA) is a heterocyclic compound found on animal skin. Its trans isomer exhibits UV-protective activity by absorbing ultraviolet (280–310 nm) radiation while isomerizing to the cis isomer [3,4]. In addition, UA has potential as a pharmaceutical compound because it strongly inhibits natural killer cell activity [5]. Furthermore, 4-vinylimidazole, which is obtained by decarboxylating UA, can be polymerized into a vinyl monomer in polymer materials [6]. Thus, UA is a promising metabolite for use in the pharmaceutical and industrial fields. UA is biosynthesized as follows: First, glucose is metabolized through the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) to 5-phospho-α-D-ribose 1-diphosphate (PRPP), which is then metabolized to L-histidine by a series of enzymes encoded by the L-histidine synthesis (his) gene cluster. Finally, L-histidine is converted into L-glutamic acid by a series of enzymes encoded by the L-histidine degradation (hut) gene cluster [Figure 1]. L-Histidine is degraded to UA by L-histidine ammonia lyase (hutH) and further to imidazol-4-one-5-propionic acid (IP) by urocanate hydratase (hutU). To date, few studies have investigated microbial UA production. Kisumi et al. reported that Serratia marcescens SR41 mutants produced 10.5 g/L UA from 70 g/L glucose [7,8]. In contrast, Kobayashi et al. reported that HutU activity-deficient Corynebacterium ammoniagenes ATCC 6872 produced 7.2 g/L UA from 10 g/L L-histidine [9]. Furthermore, a mutant conferring resistance to histidine analogs such as 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT) produced 7.3 g/L UA from 120 g/L glucose. This study suggests that UA can be produced by disrupting hutU and overexpressing hutH in C. ammoniagenes. However, UA production using genetically engineered C. ammoniagenes has not yet been reported, as the genetic engineering of C. ammoniagenes has only recently been established.

| Figure 1: Biosynthesis of L-histidine and urocanic acid from glucose in Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 and Corynebacterium ammoniagenes NBRC 12071. The box indicates the engineering demonstrated in this study. PPP: Pentose phosphate pathway, PRPP: 5-phospho-α-D-ribose 1-diphosphate, IP: 4-imidazolone-5-propanoate, his: L-histidine synthesis genes, hut: L-histidine degradation genes.

[Click here to view] |

C. ammoniagenes is a coryneform bacterium used in the industrial production of various metabolites such as amino acids and nucleotides [10]. C. ammoniagenes has high ammonia production capacity and shows optimal growth at pH 7.0–8.5 [11]. In 2017, the complete genome sequence of C. ammoniagenes 9.6 (ATCC 6871) was deposited in GenBank. This revealed that C. ammoniagenes has his and hut gene clusters and produces UA as an intermediate metabolite in the histidine degradation pathway. In contrast, Corynebacterium glutamicum does not possess the hut gene cluster. Thus, L-histidine degradation is a characteristic metabolic process in C. ammoniagenes [12,13]. Several studies on the genetic engineering of C. ammoniagenes have been reported. Koizumi and Teshiba overexpressed the riboflavin synthesis gene in C. ammoniagenes and consequently succeeded in producing 15.3 g/L riboflavin [14]. They used a DNA fragment from C. ammoniagenes ATCC 6872 genomic DNA, which showed high homology with the valine tRNA promoter from Bacillus subtilis, as the promoter. Stolle et al. overexpressed the small subunit of ribonucleotide reductase in C. ammoniagenes ATCC 6872 using the tac promoter, which is functional in both Escherichia coli and C. ammoniagenes [15]. Hou et al. cloned various promoters from C. ammoniagenes ATCC 6871 and examined the fluorescence intensities after fusion with the red fluorescent protein gene [16]. Consequently, we identified a strong 50S ribosomal protein promoter (Prpl21). As the expression vector for C. ammoniagenes, pXMJ19 has been constructed [17]. This shuttle vector contains both pUC and pBL1 replicons that function in E. coli and C. glutamicum. Electroporation can also be used to transform C. ammoniagenes [18]. To determine the role of the cysteine methionine regulator gene in sulfur metabolism in C. ammoniagenes, Lee et al. demonstrated gene disruption in C. glutamicum through homologous recombination [19].

These findings suggest that genetically engineered C. ammoniagenes can produce UA. This study aimed to demonstrate UA production from glucose by disrupting hutU and overexpressing hutH in C. ammoniagenes [Figure 1]. The goal of this study is to develop an industrial UA production process. Glucose was used in this study because it is a fundamental substrate. In addition, it would be possible to make UA production a sustainable process by using alternative low-cost sources, such as raw materials and organic waste, instead of glucose. UA is expected to be more soluble under alkaline conditions than under neutral conditions because the pKa of UA is 6.1 [20,21]. This suggests that alkaline conditions are suitable for microbial UA production. As noted previously, C. ammoniagenes grows under weakly alkaline conditions, suggesting that it is suitable for UA production [11]. In addition, to demonstrate the usefulness of the hutU disruptant constructed in this study, we attempted to construct spontaneous mutants from the disruptant with 3-AT.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Strains and Plasmids

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. The primer sequences and plasmid maps are presented in Table S1 and Figure S1, respectively. A schematic diagram of the construction of engineered C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 is shown in Figure S2. In this study, the type strain C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 (ATCC 6871) was used as the parent strain for UA production. The backbone of plasmid pUC18 [22] and hutU derived from C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 were amplified by PCR with pUC18 and C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 genome, respectively, as templates using the primer sets pUC18_F and pUC18_R and hutU-5′-F and hutU-3′-R, respectively. PCR was performed using Q5 DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA). The amplified fragments were ligated using Gibson Assembly Master Mix (New England Biolabs Inc.) to obtain the plasmid pUC18–hutU. To insert the kanamycin resistance gene into hutU on pUC18–hutU, PCR amplicons were obtained with pUC18–hutU and pK18mobsacB [23], respectively, as the templates using the primer sets hutU-3′-F and hutU-5′-R and KanR_F and KanR_R, respectively, and then ligated using the Gibson Assembly, resulting in a plasmid pUC18–ΔhutU. The backbone of plasmid pXMJ19 [17], Prpl21 derived from C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071, and green fluorescent protein gene (gfp) were amplified by PCR from pXMJ19, C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 genome, and pGreenTIR [24], respectively, as templates using the primer sets pXMJ19-F and pXMJ19-R, Prpl21-F and Prpl21-R, and pXMJ19–Prpl21–gfp-F and pXMJ19–Prpl21–gfp-R, respectively. The amplified fragments were ligated using Gibson Assembly, forming the plasmid pXMJ19–Prpl21–gfp. C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 was transformed with pXMJ19 and pXMJ19–Prpl21–gfp through electroporation [18], resulting in the MM2 and MM3 transformants, respectively. Electroporation was done under the condition of 12.5 kV/cm, 25 μF, and 200 Ω. To replace the hutH derived from C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 with gfp on pXMJ19–Prpl21–gfp, PCR amplicons were obtained with pXMJ19–Prpl21–gfp and C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 genome as templates using the primer sets pXMJ19-F3 and pXMJ19-R3 and hutH-F and hutH-R, respectively, and then ligated using Gibson Assembly, resulting in the plasmid pXMJ19–Prpl21–hutH. The pXMJ19–Prpl21–hutH plasmid was introduced into C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 and MM1 to generate MM4 and MM5 transformants, respectively. While culturing the transformants and gene disruptants, 20 mg/L chloramphenicol and 30 mg/L kanamycin were added to the medium. The hutU and hutH sequences encoded in the genome of C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 were obtained from the GenBank database under accession number CP009244.

Table 1: Plasmids and strains used in this study.

| Plasmids and strains | Description | Source |

|---|

| Plasmids | | |

| pUC18 | Escherichia coli vector, ApR | [21] |

| pK18mobsacB | KmR source | [22] |

| pUC18–ΔhutU | pUC18 harboringhutU::KmR | This work |

| pXMJ19 | Escherichia coli–Corynebacterium glutamicum shuttle vector, CmR | [16] |

| pGreenTIR | gfp source | [23] |

| pXMJ19–Prpl21–gfp | pXMJ19 harboring Prpl21 andgfp | This work |

| pXMJ19–Prpl21–hutH | pXMJ19 harboring Prpl21 andhutH | This work |

| Strains | | |

| Escherichia coli DH5α | Cloning host | Nippon Gene Co. |

| Corynebacterium ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 | Type strain | NBRC |

| MM1 | NBRC 12071 (hutU::KmR) | This work |

| MM2 | NBRC 12071 (pXMJ19) | This work |

| MM3 | NBRC12071 (pXMJ19–Prpl21–gfp) | This work |

| MM4 | NBRC12071 (pXMJ19–Prpl21–hutH) | This work |

| MM5 | MM1 (pXMJ19–Prpl21–hutH) | This work |

After C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 was treated with N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (NTG), the cell viability was determined [Figure S3]. C. ammoniagenes MM1 was similarly treated with 2000 μg/mL NTG and cultivated on minimum medium [0.1 g/L KH2PO4, 0.3 g/L K2HPO4, 2 g/L urea, 3 g/L NH4Cl, 0.3 g/L MgSO4·7H2O, 10 mg/L FeSO4·7H2O, 1 mg/L ZnSO4·7H2O, 4 mg/L MnSO4·H2O, 0.2 mg/L CuSO4·5H2O, 10 mg/L CaCl2·2H2O, 40 mg/L L-cysteine hydrochloride·H2O, 10 mg/L thiamin hydrochloride, 0.06 mg/L biotin, 20 mg/L calcium pantothenate, 9 g/L tricine-NaOH (pH 8.5)] containing 2% glucose [25] and 1 mg/mL 3-AT. After cultivating at 37°C for 3 days, 12 3-AT resistant colonies were obtained.

2.2. Effect of Culture pH on C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 Growth

C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 was pre-cultivated in 5 mL IFO 802 medium (10 g/L hipolypepton, 2 g/L yeast extract, 1 g/L MgSO4·7H2O) for 1 d at 30°C with shaking. The culture was inoculated into 30 mL IFO 802 medium supplemented with 0.1 M MOPS (pH 7.0), tricine-NaOH (pH 8.5), or CAPS (pH 10.0) at OD600 of 0.1. The OD600 and pH of the cultures were monitored during cultivation at 30°C with shaking. This cultivation was performed in triplicate, and the average was determined with errors indicating the standard deviations.

2.3. Gene Disruption

C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 was transformed with pUC18–ΔhutU by electroporation method [18]. The resulting transformant MM1 was obtained after cultivation on the brain heart infusion (BHI; BD Difco, NJ, USA) agar plates containing 91.1 g/L sorbitol and 30 mg/L kanamycin for 3 days at 30°C. hutU disruption was confirmed by PCR [Figure S4].

2.4. UA Production

A series of strains were pre-cultured in 5 mL BHI medium for 1 day at 30°C with shaking. The culture was inoculated into 30 mL BHI medium at OD600 of 0.1, cultivated for 1 day at 30°C with shaking, and then washed with saline solution. For UA production using resting cells, the cells were resuspended in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 10 mM L-histidine at OD600 of 5.0 and then incubated for 3 days at 30°C with shaking. This cultivation was performed in duplicate, and the average was determined with error bars indicating the standard deviations. For UA production using growing cells, the cells were inoculated into 50 mL minimum medium supplemented with 2% glucose at OD600 of 0.1 and then cultivated for 7 days at 30°C with shaking. The supernatants of the cell suspensions and cultures were analyzed for UA and L-histidine production. This cultivation was performed in duplicate, and the average was determined with error bars indicating the standard deviations. The UA titer, specific production rate, and yield from glucose obtained in this study are summarized in Table S2.

2.5. Evaluation of GFP Expression with Prpl21

After MM2 and MM3 were cultivated in 5 mL BHI medium containing 20 mg/L chloramphenicol for 1 day at 30°C with shaking, the cells were washed and resuspended in saline solution. The fluorescence of the cell suspensions was monitored using a spectrofluorometer FP-6500 (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan). A 490-nm light was used for excitation, and the emission wavelength was set at 510 nm.

2.6. Analysis Methods

A glucose CII Test Kit (Fujifilm Wako Co., Osaka, Japan) was used to determine the glucose concentration in the cultures. L-Histidine and UA in the culture supernatant were derivatized with dabsyl chloride [26] and analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography. The analytes were eluted with solvent A (50 mM sodium acetate buffer [pH 6.5]) and solvent B (the same buffer containing 70% acetonitrile) under gradient conditions. The gradient was 100–30% solvent A from 0 to 1 min, 30–0% solvent A from 1 to 25 min, 0% solvent A from 25 to 30 min, 100% solvent A from 30 to 40 min, and 0% solvent B from 30 to 40 min. Calibration curves of L-histidine and UA after derivatization are shown in Figure S5.

The dry cell weight of C. ammoniagenes was calculated by correlating it with the OD600 value (1 OD600 = 0.29 g-cells/L). In detail, C. ammoniagenes were dried at 80°C for 18 h and then the dry cell weight was obtained to determine the correlation of OD600 to dry cell weight (g). The specific growth rate (µ) was calculated as the slope of the regression line from a plot of ln(Xt/X0) and time (t) during the exponential growth period, where Xt (g-cells/L) and X0 (g-cells/L) are the cell concentrations at t (h) and at the beginning of the exponential phase, respectively. The specific production rate of UA was calculated as follows: Specific production rate = (UAt – UA0)/(Xt – X0) × µ; UAt, the UA concentration (mg/L) at t (h); UA0, the UA concentration (mg/L) at the beginning of the exponential phase.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Effect of Culture pH on C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 Growth

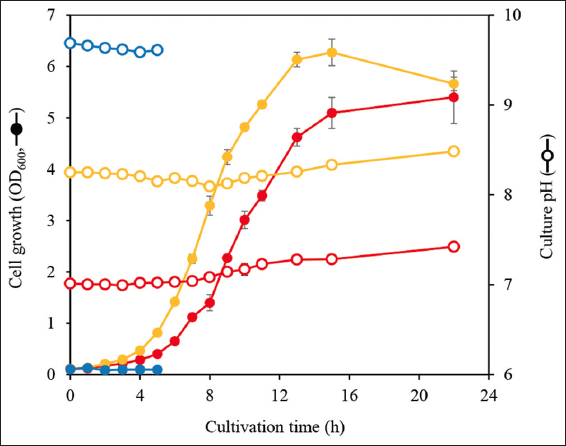

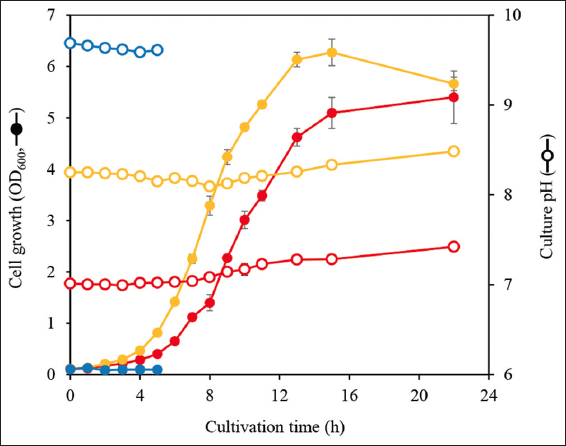

C. ammoniagenes grows under weak alkaline conditions [11]. To confirm C. ammoniagenes growth under alkaline conditions believed to be suitable for microbial UA production, wild-type strain C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 was cultivated at pH 7.0, 8.5, and 10.0. As expected, the strain grew at pH 7.0 (µ = 0.30 ± 0.12 h−1) and pH 8.5 (µ = 0.37 ± 0.07 h−1) but did not grow at pH 10.0 [Figure 2]. While the pH of the designed medium remained relatively stable across all treatments owing to its buffering capacity, C. ammoniagenes growth was well supported at an initial pH of 8.5. Based on this result, pH 8.5 was used as the culture pH in subsequent experiments for UA production.

| Figure 2: Effect of culture pH on growth of Corynebacterium ammoniagenes NBRC 12071. The strain was cultivated in IFO 802 medium supplemented with 0.1 M MOPS (pH 7.0, red), tricine-NaOH (pH 8.5, yellow), or CAPS (pH 10.0, blue). Solid symbols, cell growth (OD600); open symbols, culture pH. The cultivation at pH 10.0 was stopped at 5 h because the strain showed no growth. This cultivation was performed in triplicate, and the average was represented with error bars indicating the standard deviations.

[Click here to view] |

3.2. Effect of hutU Disruption on UA Production

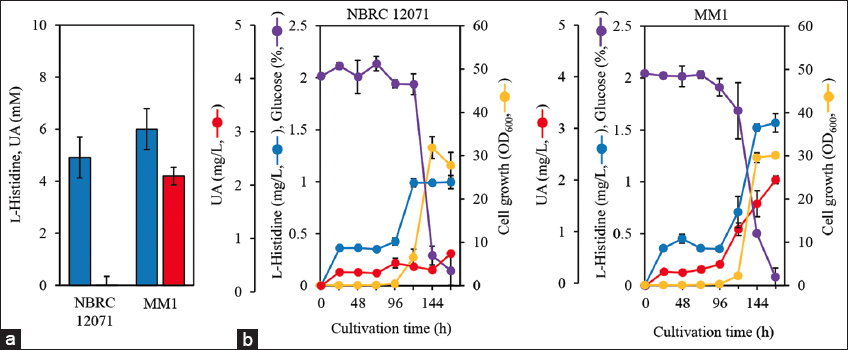

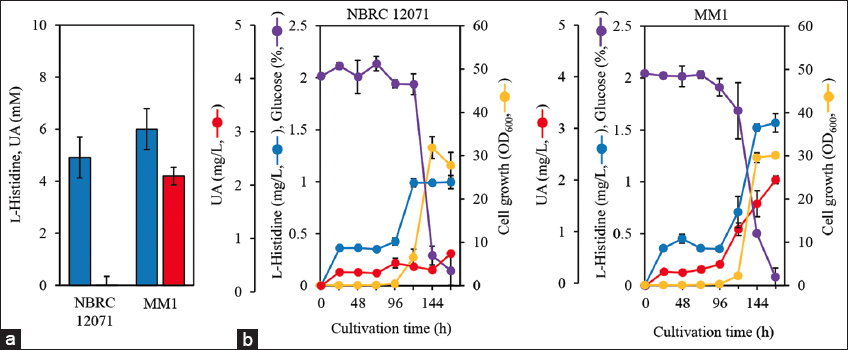

It was confirmed that hutU was disrupted as expected because the hutU disruption locus was amplified by PCR without an unspecific amplicon [Figure S4]. To evaluate the effect of hutU disruption on UA production, resting cells of C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 and the hutU-disruptant MM1 were incubated for 3 days with 10 mM L-histidine. C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 and MM1 consumed 5.1 ± 0.8 and 4.0 ± 0.4 mM L-histidine and produced 0.2 ± 0.0 μM and 4.2 ± 0.3 mM UA, respectively [Figure 3a]. Thus, hutU is suggested to be expressed in C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071, and UA yield from L-histidine by MM1 was nearly 100%. This finding suggests that hutU is not expressed in MM1 and that hutU is a unique gene for UA conversion in C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 and that hutU disruption is effective for UA production. Interestingly, L-histidine consumption in MM1 was reduced than in the wild-type strain. This suggests that HutH activity was reduced by product inhibition, and consequently, L-histidine consumption was reduced. Such inhibitory effects of UA on HutH have been observed in some microbes, such as Pseudomonas putida [12] and Aspergillus nidulans [27].

| Figure 3: (a) Production of urocanic acid (UA; red bars) from 10 mM L-histidine (blue bars) in the resting cells of Corynebacterium ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 and MM1. The cells were resuspended in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 10 mM L-histidine at OD600 of 5.0 and then incubated for 3 days at 30°C with shaking. This assay was performed in triplicate, and the average was presented with error bars representing standard deviations. (b) Cell growth and L-histidine and UA production from 2% glucose in the growing cells of C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 and MM1. The cells were inoculated to 50 mL minimum medium supplemented with 2% glucose at OD600 of 0.1 and then cultivated for 7 days at 30°C with shaking. Red, UA concentration; blue, L-histidine concentration; yellow, cell growth (OD600); purple, glucose concentration. This cultivation was performed in duplicate, and the average was represented with error bars indicating the standard deviations.

[Click here to view] |

C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 growing cells produced a trace amount of UA (0.62 mg/L) from 2% glucose even after 7 days of cultivation, while MM1 produced 2.0±0.1 mg/L UA with 0.29±0.00 mg/g-cells/day specific production rate [Figure 3b]. This indicates that hutU disruption in C. ammoniagenes enables the direct UA production from glucose. Both strains showed similar profiles of glucose consumption and cell growth; however, their UA production and L-histidine consumption profiles were different. Cell growth showed a lag time in the initial phase, which may be due to the use of minimum medium in this study. Particularly, MM1 showed less cell growth (OD600 = 2.23 ± 0.36) than the wild-type strain (OD600 = 6.55 ± 1.90) after 120 h cultivation. This may be due to the lack of L-glutamate in MM1 because UA is the precursor of L-glutamate. C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 genome contains a gene encoding glutamate dehydrogenase (Gdh), which generates L-glutamate from 2-oxoglutarate. Gdh may supply L-glutamate to MM1, and consequently, partially support cell growth. C. glutamicum produces L-glutamate from 2-oxoglutarate through Gdh in the same manner [28]. These findings also suggest that L-glutamate supplementation or gdh overexpression in the MM1 strain improves cell growth and UA production. The kanamycin resistance marker derived from pK18mobsacB, which has often been used for gene disruption in C. glutamicum [29,30], was used for hutU disruption in this study, suggesting that the resistance marker did not affect the metabolism of C. ammoniagenes.

Kobayashi et al. have constructed a spontaneous mutation from HutU activity-deficient C. ammoniagenes ATCC 6872 using a series of histidine analogs, including 3-AT, which consequently enhanced UA production [9]. To prove that the hutU-disruptant MM1 can be also used for constructing UA-producing spontaneous mutants, we constructed a 3-AT resistant MM1 mutant using NTG treatment. Prior to the construction of the mutant, the conditions for NTG treatment of C. ammoniagenes NBRC 12071 were optimized. The results clarified that treating with 2000 μg/mL NTG for 30 min resulted in a 0.97% cell viability [Figure S3]. We concluded that this condition was suitable for the mutation. Using these conditions, 12 3-AT resistant strains were obtained from the hutU disruptant. Interestingly, of which, 3 3-AT resistant strains produced 0.16–0.29 g/L UA from 2% glucose (data not shown). The isolation efficiency of mutants producing UA at non-negligible levels was calculated to be 25%. This indicates that the hutU disruptant was useful for constructing UA-producing spontaneous mutants.

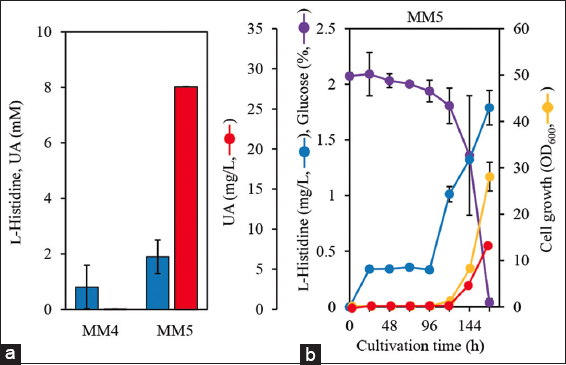

MM5 cells cultured in minimum medium containing 2% glucose for 7 days produced 7.7 ± 0.3 mg/L UA with 1.73 ± 0.12 mg/g-cells/day specific production rate. The specific production rate was 6.0 times higher than that of MM1 [Figure 4b]. This indicates that hutH overexpression partially improved UA production when glucose was used as the carbon source. One possible reason for the lack of a significant enhancement in UA production is that L-histidine production may be one of the rate-limiting steps in UA production. In addition, MM5 showed significant less growth (OD600 = 8.1 ± 0.4) than MM1 (OD600 = 29.6 ± 1.1) after 144 h. During cultivation, the L-histidine level in MM5 was similar to that in MM1. These findings suggest that hutH overexpression has negative effects on cell growth and energy consumption. Kobayashi et al. demonstrated to produce UA using a C. ammoniagenes mutant cultivated in a semi-synthetic medium supplemented with 10 g/L meat extract [9]. The negative effects observed in this study would be recovered by adding such nutrient components to the medium.

REFERENCES

1. Pham JV, Yilma MA, Feliz A, Majid MT, Maffetone N, Walker JR, et al. A review of the microbial production of bioactive natural products and biologics. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1404.[CrossRef]

2. Lee SY, Kim HU. Systems strategies for developing industrial microbial strains. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(10):1061-72.[CrossRef]

3. Kavanagh G, Crosby J, Norval M. Urocanic acid isomers in human skin:Analysis of site variation. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133(5):728-31.[CrossRef]

4. McLoone P, Simics E, Barton A, Norval M, Gibbs NK. An action spectrum for the production of cis-urocanic acid in human skin in vivo. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124(5):1071-4.[CrossRef]

5. Uksila J, Laihia JK, Jansén CT. Trans-urocanic acid, a natural epidermal constituent, inhibits human natural killer cell activity in vitro. Exp Dermatol. 1994;3(2):61-5.[CrossRef]

6. Michael MH Jr., Hemp ST, Smith AE, Long TE. Controlled radical polymerization of 4-vinylimidazole. Macromolecules. 2012;45(9):3669-76.[CrossRef]

7. Kisumi M, Nakanishi N, Takagi T, Chibata I. L-Histidine production by histidase-less regulatory mutants of Serratia marcescens constructed by transduction. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1977;34(5):465-72.[CrossRef]

8. Kisumi M, Nakanishi N, Takagi T, Chibata I. Construction of a urocanic acid-producing strain of Serratia marcescens by transduction. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;35(2):231-6.[CrossRef]

9. Kobayashi S, Araki K, Nakayama K. Accumulation of urocanic acid by mutant strains of Brevibacterium ammoniagenes. J Agric Chem Soc Jpn. 1977;51(9):543-50.

10. Chung SO, Lee JH, Lee SY, Lee DS. Genomic organization of purK and purE in Brevibacterium ammoniagenes ATCC 6872:purE locus provides a clue for genomic evolution. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;137(2-3):265-8.[CrossRef]

11. Ratzke C, Gore J. Modifying and reacting to the environmental pH can drive bacterial interactions. PLoS Biol. 2018;16(3):2004248.[CrossRef]

12. Bender RA. Regulation of the histidine utilization (hut) system in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2012;76(3):565-84.[CrossRef]

13. Schwentner A, Feith A, Münch E, Stiefelmaier J, Lauer I, Favilli L, et al. Modular systems metabolic engineering enables balancing of relevant pathways for L-histidine production with Corynebacterium glutamicum. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2019;12:65.[CrossRef]

14. Koizumi S, Teshiba S. Riboflavin biosynthetic genes of Corynebacterium ammoniagenes. J. Ferment Technol. 1988;86(1):130-3.[CrossRef]

15. Stolle P, Barckhausen O, Oehlmann W, Knobbe N, Vogt C, Pierik AJ, et al. Homologous expression of the nrdF gene of Corynebacterium ammoniagenes strain ATCC 6872 generates a manganese-metallocofactor (R2F) and a stable tyrosyl radical (Y´) involved in ribonucleotide reduction. FEBS J. 2010;277(23):4849-62.[CrossRef]

16. Hou Y, Chen S, Wang J, Liu G, Wu S, Tao Y. Isolating promoters from Corynebacterium ammoniagenes ATCC 6871 and application in CoA synthesis. BMC Biotechnol. 2019;19:76.[CrossRef]

17. Jakoby M, Ngouoto-Nkili CE, Burkovski A. Construction and application of new Corynebacterium glutamicum vectors. Biotechnol Tech. 1999;13:437-41.[CrossRef]

18. Liebl W, Bayerl A, Schein B, Stillner U, Schleifer KH. High efficiency electroporation of intact Corynebacterium glutamicum cells. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1989;53(3):299-303.[CrossRef]

19. Lee SM, Hwang BJ, Kim Y, Lee HS. The cmaR gene of Corynebacterium ammoniagenes performs a novel regulatory role in the metabolism of sulfur-containing amino acids. Microbiol (Reading). 2009;155(6):1878-89.[CrossRef]

20. Roberts JD, Chun Y, Flanagan C, Birdseye TR. A nitrogen-15 nuclear magnetic resonance study of the acid-base and tautomeric equilibriums of 4-substituted imidazoles and its relevance to the catalytic mechanism of.alpha.-lytic protease. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104(14):3945-9.[CrossRef]

21. Krien PM, Kermici M. Evidence for the existence of a self-regulated enzymatic process within the human stratum corneum -an unexpected role for urocanic acid. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115(3):414-20.[CrossRef]

22. Norrander J, Kempe T, Messing J. Construction of improved M13 vectors using oligodeoxynucleotide-directed mutagenesis. Gene. 1983;26(1):101-6.[CrossRef]

23. Tan Y, Xu D, Li Y, Wang X. Construction of a novel sacB-based system for marker-free gene deletion in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Plasmid. 2012;67(1):44-52.[CrossRef]

24. Miller WG, Lindow SE. An improved GFP cloning cassette designed for prokaryotic transcriptional fusions. Gene. 1997;191(2):149-53.[CrossRef]

25. Koizumi S, Yonetani Y, Maruyama A, Teshiba S. Production of riboflavin by metabolically engineered Corynebacterium ammoniagenes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;53:674-9.[CrossRef]

26. Takahashi M, Tezuka T. Quantitative analysis of histidine and cis and trans isomers of urocanic acid by high-performance liquid chromatography:A new assay method and its application. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 1997;688(2):197-203.[CrossRef]

27. Polkinghorne MA, Hynes MJ. L-Histidine utilization in Aspergillus nidulans. J Bacteriol. 1982;149(3):931-40.[CrossRef]

28. Sheng Q, Wu XY, Xu X, Tan X, Li Z, Zhang B. Production of L-glutamate family amino acids in Corynebacterium glutamicum:Physiological mechanism, genetic modulation, and prospects. Synth Syst Biotechnol. 2021;6(4):302-25.[CrossRef]

29. Wang Q, Zhang J, Zhao Z, Li Y, You J, Wang Y, et al. Dual genetic level modification engineering accelerate genome evolution of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52(14):8609-27.[CrossRef]

30. Xu J, Xia X, Zhang J, Guo Y, Qian H, Zhang W. A method for gene amplification and simultaneous deletion in Corynebacterium glutamicum genome without any genetic markers. Plasmid. 2014;72:9-17.[CrossRef]