1. INTRODUCTION

Biologics and biosimilar represent a significant leap in pharmaceutical innovation, offering targeted and efficient therapies for life-threatening and chronic diseases. Biologics are sophisticated treatments derived from living organisms, produced through advanced biotechnological processes, and extensively applied in oncology, immunology, and the treatment of rare genetic diseases. Biosimilar, which exhibits a high degree of similarity to authorized reference biologics with no clinically significant variations in effectiveness or safety, is intended to enhance affordability and access for a broader range of patient populations [1]. According to recent market analyses, biologics account for more than 40% of worldwide pharmaceutical Research and Development spending, largely due to their growing prominence in contemporary healthcare. As global demand grows, there is a pressing need to establish sustainable methods that reduce production costs, conserve resources, and provide equal access across different geographies. Although biosimilar are cost-effective, their production still requires extensive testing, specialized manufacturing facilities, and stringent regulatory requirements. Despite their potential, the production and use of biologics and biosimilar are hindered by issues such as high energy requirements, the application of animal-based materials, and stringent quality control measures [2]. These limitations underscore the need to leverage innovative technologies, including drug design and green bioprocessing, thereby enhancing the robustness of sustainability. This review undertakes a critical assessment of the sustainable methods currently employed in biologic and biosimilar development, identifying gaps in the traditional approach and proposing integrative solutions that incorporate technology, policy, and clinical research. Major areas of focus include structural complexity, production platforms, immunogenicity, regulatory policy, and market integration, everything viewed through the prism of sustainability.

2. METHODOLOGY

This review aimed to critically examine sustainable strategies in biologic and biosimilar development, with emphasis on manufacturing, regulatory environments, immunogenicity, and new technologies. An extensive literature search was conducted using databases such as PubMed, Scopus, ScienceDirect®, and Google Scholar, covering the period from 2015 to 2025. Keywords such as “biosimilar,” “biologics,” “green bioprocessing,” “biopharmaceutical manufacturing,” “sustainability,” and “regulatory harmonization” were searched in different combinations. Articles were selected based on relevance, scientific validity, and emphasis on sustainability, excluding non-English publications and studies with methodological flaws. Moreover, regulatory guidelines were downloaded from official websites such as the United States Food and Drug Administration (U.S. FDA), European Medicines Agency (EMA), World Health Organization, and Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO). Literature was critically reviewed, thematically arranged, and synthesized to provide a consolidated overview of existing developments and issues in the sustainable development of biologics and biosimilars.

2.1. Structural and Functional Complexity of Biologics

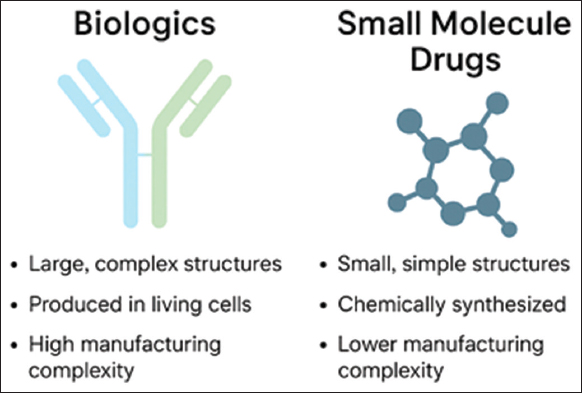

Biologics are therapeutic agents derived from living systems such as microbial, animal, or human cells and are characterized by large, structurally complex macromolecules, including proteins, nucleic acids, and polysaccharides. Unlike chemically synthesized small molecule drugs, which have well-defined and reproducible structures, biologics exhibit inherent heterogeneity due to their biosynthetic origin. This complexity necessitates stringent manufacturing controls to ensure product consistency and safety [3]. A critical aspect of biologics is their structural complexity, which often includes post-translational modifications (PTMs) such as glycosylation, phosphorylation, and folding factors essential for biological activity. For example, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) possess multiple subunits, disulfide bonds, and highly specific antigen-binding sites that require exact structural configuration. Even minor variations in tertiary or quaternary structures can affect therapeutic efficacy and immunogenicity [4]. Maintaining batch-to-batch consistency remains a significant challenge. Advanced analytical techniques such as mass spectrometry, X-ray crystallography, and high-performance liquid chromatography are routinely used to assess critical quality attributes (CQAs) [5]. However, despite technological advancements, complete structural characterization remains difficult, and some degree of variability is typically accepted within defined regulatory thresholds.

2.2. Functional Implications

Biologics have highly specific mechanisms of action, achieved through receptor binding, immune modulation, or enzymatic activity. Such mechanisms frequently require the presence of fine structural detail and are thereby highly sensitive to manufacturing conditions [6]. Interactions with the immune system can result in immunogenicity, which requires preclinical and clinical testing to identify the formation of anti-drug antibodies. This combined structural and functional complexity calls for sophisticated manufacturing and regulatory management. From the point of sustainability, these operations need large amounts of energy, water, and raw material inputs. Fine-tuning these parameters through green bioprocessing, digital twins, and continuous monitoring has the potential to decrease environmental load without diminishing therapeutic integrity. Figure 1 illustrates a comparison between biologics and small-molecule drugs in molecular size, structural complexity, manufacturing process, and regulatory control. Biologics, such as mAbs, are complex, heterogeneous molecules produced in living systems, necessitating intricate purification and quality control. Small molecule pharmaceuticals are chemically produced, have well-specified structures, and relatively simple manufacturing processes. The figure highlights key differences pertinent to therapeutic design, scalability, and sustainability issues.

2.3. Recombinant Protein-based Therapeutics

Recombinant protein therapeutics have emerged as a cornerstone of biologic drug discovery, fundamentally transforming the management of chronic, infectious, and genetic disorders by enabling highly specific, mechanism-based interventions [7]. Unlike conventional small molecules, which often exert pleiotropic effects with variable selectivity, recombinant proteins are designed to replicate, enhance, or modulate endogenous bimolecular pathways, thereby conferring superior therapeutic precision [8]. Their development is enabled through genetically engineered expression systems, such as Escherichia coli, yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Pichia pastoris), Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, and, more recently, plant-based and insect-cell platforms [9]. Each of these host systems presents distinct strengths and limitations that significantly shape therapeutic quality, cost, and scalability. E. coli remains the most widely used microbial expression system due to its rapid doubling time, well-characterized genetics, and cost-effectiveness; however, its lack of PTM machinery often results in mis-folded proteins or the need for refolding from inclusion bodies [10]. Yeast systems provide higher eukaryotic folding and secretion capabilities but are limited by non-human glycosylation patterns that may elicit immunogenic responses [11]. CHO cells, considered the “gold standard” for complex biologics, generate human-compatible glycosylation and high product fidelity. However, their extended culture duration and expensive media requirements make them less cost-efficient [12]. Plant-based systems have garnered attention for their scalability and biosafety profile; however, they face ongoing regulatory skepticism and batch-to-batch variability [13]. The choice of expression platform is therefore not merely technical, but strategic, influencing downstream purification complexity, regulatory approval, and ultimately patient accessibility. While microbial systems dominate in the production of relatively simple proteins such as insulin or growth hormones, mAbs and fusion proteins, which require precise PTMs, are almost exclusively produced in mammalian systems [14]. Increasingly, hybrid strategies such as glycoengineered yeast or plant lines are being investigated to combine the low cost advantages of non-mammalian hosts with the functional fidelity of mammalian cells [15]. This reflects a broader paradigm shift in recombinant protein engineering, aiming to balance clinical efficacy, economic sustainability, and global accessibility.

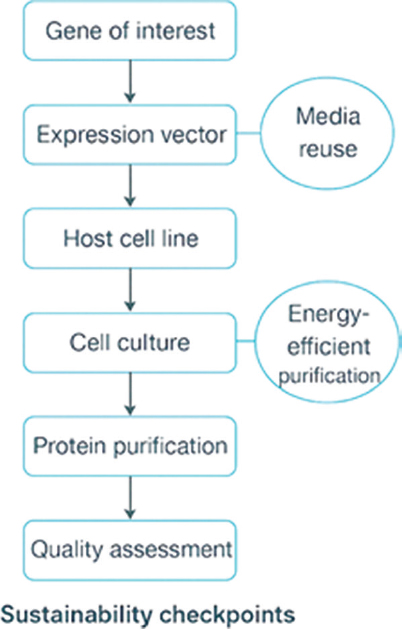

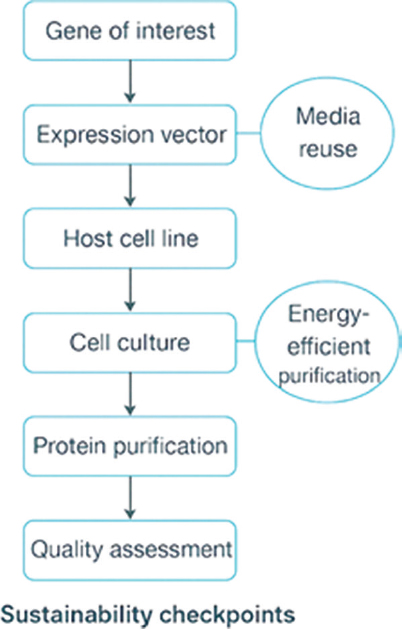

A landmark achievement in recombinant protein therapeutics was the approval of recombinant human insulin in 1982, which not only revolutionized diabetes care but also validated recombinant DNA technology as a viable pharmaceutical platform [16]. This breakthrough paved the way for mAbs and fusion proteins, which have since become the dominant segment of biologics, setting new standards for therapeutic specificity, clinical efficacy, and reduced off-target toxicity [17]. Despite this success and a forecasted global market exceeding USD 203 billion by 2029 [18], formidable challenges remain. Chief among these are immunogenicity risks arising from subtle glycosylation differences, the high cost and complexity of large-scale production, and sustainability concerns linked to resource-intensive upstream and downstream processes [19,20]. Moreover, regulatory heterogeneity across jurisdictions complicates biosimilar approvals, slowing equitable patient access. Thus, the field must reconcile clinical innovation with affordability, manufacturability, and global accessibility. Thus, while recombinant platforms have revolutionized biologics, their future trajectory depends on striking a balance between clinical efficacy, affordability, and sustainability. Figure 2 illustrates a flowchart of recombinant protein production, highlighting key sustainability checkpoints, including the reuse of media and energy efficient purification.

| Figure 2: Pipeline of recombinant protein production with sustainability checkpoints.

[Click here to view] |

2.4. Multifaceted Challenges in Biosimilar Development and Adoption

The development of biosimilar presents a unique set of scientific, regulatory, manufacturing, and market related challenges that distinguish them from traditional small-molecule generics. Biologics, due to their inherent structural complexity and sensitivity to manufacturing conditions, require a biosimilar to demonstrate a high degree of similarity, not identity, to the reference products in terms of structure, function, safety, and efficacy. This necessitates extensive analytical comparability studies using advanced techniques, such as liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS), capillary electrophoresis, and bioassays, to assess CQAs such as glycosylation profiles, aggregation, and binding affinity. However, minor variations can still arise due to differences in cell lines, expression systems, or purification methods.

To ensure the reliability and safety of biosimilar, it is imperative to critically evaluate primary research studies that assess their comparability to reference biologics. These studies often employ advanced analytical techniques, such as LC-MS, capillary electrophoresis, and bioassays, to evaluate CQAs like glycosylation patterns, aggregation, and binding affinities. A study assessing the degradation profiles of biosimilar anti-VEGF mAbs under thermal stress conditions highlighted differences between biosimilar and their originators, which were sourced from different regions. Such findings stress the need for rigorous and standardized analytical methods to detect subtle variations that could impact therapeutic efficacy [21]. Moreover, the FDA’s draft guidance on the development of therapeutic protein biosimilar emphasizes the necessity for comprehensive analytical assessments. However, critics suggest that the guidance may not fully address the complexities involved in demonstrating biosimilarity, particularly concerning the interchangeability of biosimilars with reference products.

Consequently, biosimilar manufacturers must invest heavily in process validation, scale-up optimization, and continuous quality monitoring, which significantly increase costs and development timelines [22]. Primary research studies in biologics manufacturing often present data that, while valuable, may lack the depth required for comprehensive process optimization. Studies on cell line development may report productivity metrics without addressing underlying factors such as metabolic profiles or PTMs, which are critical for ensuring consistent product quality [23]. Similarly, research on purification processes might focus on yield percentages but overlook the impact of host cell protein (HCP) co-elution or aggregate formation, both of which can affect the safety and efficacy of the final product.

Furthermore, many studies employ standard analytical techniques without considering the influence of process parameters, such as shear stress or pH fluctuations [24], which can significantly alter protein folding and bioactivity. Such oversights can lead to discrepancies between laboratory-scale findings and industrial-scale outcomes. Therefore, it is imperative to critically evaluate these studies, considering the broader context of process variability and its implications on product consistency and regulatory compliance. Integrating a more holistic approach in primary research can bridge the gap between experimental data and real-world manufacturing challenges, ultimately enhancing the reliability and quality of biologic therapeutics [25].

To strengthen the evidence base for biosimilar safety and efficacy, it is essential to critically dissect specific primary research studies that provide granular data on immunogenicity, pharmacokinetics (PKs), and therapeutic outcomes. A 2024 study comparing the immunogenicity of biosimilar natalizumab (biosim-NTZ) with its reference product (ref-NTZ) found that both induced similar anti-drug antibody (ADA) and neutralizing antibody (nAb) responses in healthy subjects and patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis [26]. This suggests comparable immunogenic profiles, which are crucial for assessing long-term safety and efficacy. PK equivalence was demonstrated in a 2023 trial of the proposed tocilizumab biosimilar, MSB11456, where the PK profiles, safety, and immune responses were similar to those of the US-licensed reference tocilizumab [27]. A 2023 study on MW031, a denosumab biosimilar, confirmed similar PKs, pharmacodynamics (PD), safety, and immunogenicity profiles to the reference product in healthy Chinese participants [28]. These studies highlight the importance of rigorous evaluation of primary research to ensure the safety, efficacy, and interchangeability of biosimilar, particularly when considering the extrapolation of indications. By carefully evaluating the design, methodology, and findings of these primary studies, researchers can draw nuanced conclusions regarding biosimilar interchangeability, indication extrapolation, and patient safety, thereby informing regulatory decisions and clinical practice with greater confidence.

Beyond technical and regulatory concerns, biosimilar also face significant market and perception challenges. Adoption may be hindered by skepticism among clinicians and patients regarding the equivalence of these biologics to originator biologics [29]. While policy and perception issues are important, the evidence base supporting biosimilar use relies heavily on primary research studies, which must be critically evaluated. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing biosimilar to their originator biologics have generally demonstrated comparable efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity profiles; however, the generalizability of these findings can be limited by factors such as sample size, patient selection, trial duration, and endpoint definitions [30]. Observational studies and real-world evidence provide complementary insights but are often subject to confounding and bias, highlighting the need for careful methodological evaluation. Comparative effectiveness studies in diverse patient populations can reveal differences in immunogenic responses or adverse events that may not be evident in controlled trial settings. Pharmacovigilance data are equally critical, but variations in reporting practices and follow-up periods can influence the interpretation of safety outcomes [31]. Therefore, a systematic and critical appraisal of both RCTs and observational studies is essential to ensure that clinical decisions regarding biosimilar adoption are informed by robust, transparent, and contextually relevant evidence. This approach will enhance confidence among clinicians and support the development of policies for biosimilar utilization. Transparent post-marketing surveillance data can reinforce trust by demonstrating long-term safety and efficacy. Moreover, strategic incentives such as reduced copayments, favorable formulary placement, and competitive pricing can further facilitate the uptake of biosimilar. A coordinated approach addressing scientific, regulatory, and perceptual obstacles is thus vital for the successful integration of biosimilar into routine clinical practice.

2.5. Integrated Biopharmaceutical Manufacturing: Processes and Sustainability

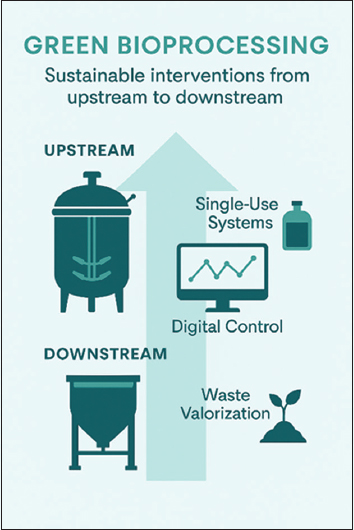

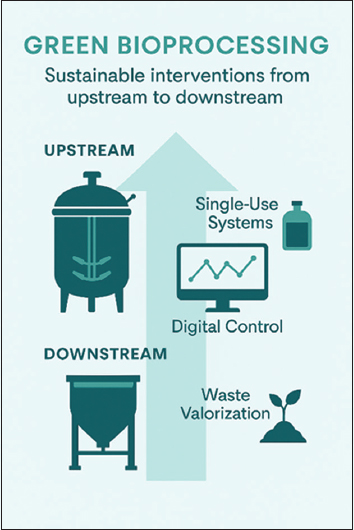

Biopharmaceutical manufacturing is a complex and highly regulated domain that encompasses the production of biologics, such as recombinant proteins, mAbs, and biosimilar. The manufacturing workflow encompasses both upstream and downstream processes, each of which is critical for ensuring product safety, efficacy, and consistency. Upstream processing encompasses cell line development, media preparation, and cell cultivation in bioreactors, typically utilizing expression systems such as CHO cells, E. coli, or yeast [32]. These processes are tightly regulated to maintain optimal parameters, including temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, and nutrient concentrations, thereby maximizing protein expression while ensuring cell viability. Advances, such as continuous and perfusion-based systems, have enhanced productivity and scalability. Downstream processing, on the other hand, involves the recovery and purification of target proteins through steps like centrifugation, filtration, chromatography, and lyophilization. Maintaining protein integrity while minimizing contaminants and endotoxins is essential. Single-use technology (SUT) has gained prominence in both upstream and downstream operations, offering advantages in sterility, turnaround efficiency, and reduced cross-contamination [33-35] [Figure 3].

| Figure 3: Green interventions in upstream and downstream bioprocessing, including single-use systems and digital twins.

[Click here to view] |

REFERENCES

1. Kang HN, Wadhwa M, Knezevic I, Ondari C, Simao M. WHO guidelines on biosimilar:Toward improved access to safe and effective products. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2023;1521(1):96-103.[CrossRef]

2. McDonnell S, Principe RF, Zamprognio MS, Whelan J. Challenges and emerging technologies in biomanufacturing of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). In:Biotechnology - Biosensors, Biomaterials and Tissue Engineering Annual. Vol. 2022. London:IntechOpen;2023. 1.[CrossRef]

3. Sahin E, Deshmukh S. Challenges and considerations in the development and manufacturing of high-concentration biologics drug products. J Pharm Innov. 2020;15(2):255-67.[CrossRef]

4. Posner J, Barrington P, Brier T, Datta-Mannan A. Monoclonal antibodies:Past, present and future. Concepts Princip Pharmacol. 2019;260:81-141.[CrossRef]

5. Nupur N, Joshi S, Gulliarme D, Rathore AS. Analytical similarity assessment of biosimilars:Global regulatory landscape, recent studies and major advancements in orthogonal platforms. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:832059.[CrossRef]

6. Mallick P, Taneja G, Moorthy B, Ghose R. Regulation of drug-metabolizing enzymes in infectious and inflammatory disease:Implications for biologics-small molecule drug interactions. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2017;13(6):605-16.[CrossRef]

7. Walsh G, Walsh E. Biopharmaceutical benchmarks 2022. Nat Biotechnol. 2022;40(12):1722-60.[CrossRef]

8. Leader B, Baca QJ, Golan DE. Protein therapeutics:A summary and pharmacological classification. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(1):21-39.[CrossRef]

9. Kim K, Choe D, Lee DH, Cho BK. Engineering biology to construct microbial chassis for the production of difficult-to-express proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2020;21:990.[CrossRef]

10. Rosano GL, Ceccarelli EA. Recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli:Advances and challenges. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:172.[CrossRef]

11. Ahmad M, Hirz M, Pichler H, Schwab H. Protein expression in Pichia pastoris:Recent achievements and perspectives for heterologous protein production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98(12):5301-17.[CrossRef]

12. Kim JY, Kim YG, Lee GM. CHO cells in biotechnology for production of recombinant proteins:Current state and further potential. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;93(3):917-30.[CrossRef]

13. Thomas DR, Penney CA, Majumder A, Walmsley AM. Evolution of plant-made pharmaceuticals. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2011;12:3220-36.[CrossRef]

14. Walsh G. Biopharmaceuticals:Recent approvals and likely future trends. N Biotechnol. 2018;40:15-20.

15. Hamilton SR, Gerngross TU. Glycosylation engineering in yeast:The advent of fully humanized yeast. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2007;18(5):387-92.[CrossRef]

16. Walsh G. Biopharmaceutical benchmarks 2018. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36(12):1136-45.[CrossRef]

17. Kaplon H, Reichert JM. Antibodies to watch in 2023. Abs. 2023;15(1):2153410.[CrossRef]

18. Ansari RA, Saghir SA, Torisky R, Husain K. Recombinant protein production:From bench to biopharming. Front Drug Des Discov. 2021;10:1-31.[CrossRef]

19. LagasséHA, Alexaki A, Simhadri VL, Katagiri NH, Jankowski W, Sauna ZE, et al. Recent advances in (therapeutic protein) immunogenicity prediction and mitigation. Front Immunol. 2017;8:113.[CrossRef]

20. Walsh G. Biopharmaceutical benchmarks 2021. Nat Biotechnol. 2021;39(6):702-10.

21. Pamukcu C, Atik AE. Assessing the comparability of degradation profiles between biosimilar and originator anti-VEGF monoclonal antibodies under thermal stress. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2025;18(9):1267.[CrossRef]

22. Tripathi NK, Shrivastava A. Recent developments in bioprocessing of recombinant proteins:Expression hosts and process development. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2019;7:420.[CrossRef]

23. Kannicht C, Ramström M, Kohla G, Tiemeyer M, Casademunt E, Walter O,et al. Characterisation of the post-translational modifications of a novel, human cell line-derived recombinant human factor VIII. Thromb Res. 2013;131(1):78-88.[CrossRef]

24. Slavik I, Müller S, Mokosch R, Azongbilla JA, Uhl W. Impact of shear stress and pH changes on floc size and removal of dissolved organic matter (DOM). Water Res. 2012;46(19):6543-53.[CrossRef]

25. Jayakrishnan A, Wan Rosli WR, Tahir AR, Razak FS, Kee PE, Ng HS, et al. Evolving paradigms of recombinant protein production in the pharmaceutical industry:A rigorous review. Science. 2024;6(1):9.[CrossRef]

26. Chamberlain P, Hemmer B, Höfler J, Wessels H, von Richter O, Hornuss C, et al. Comparative immunogenicity assessment of biosimilar natalizumab to its reference medicine:A matching immunogenicity profile. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1414304.[CrossRef]

27. Tomaszewska-Kiecana M, Ullmann M, Petit-Frere C, Monnet J, Dagres C, Illes A. Pharmacokinetics of a proposed tocilizumab biosimilar (MSB11456) versus US-licensed tocilizumab:Results of a randomized, double-blind, single-intravenous dose study in healthy adults. Exp Rev Clin Immunol. 2023;19(4):439-46.[CrossRef]

28. Guo Y, Guo T, Di Y, Xu W, Hu Z, Xiao Y, et al. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety and immunogenicity of recombinant, fully human anti-RANKL monoclonal antibody (MW031) versus denosumab in Chinese healthy subjects:A single center, randomized, double-blind, single-dose, parallel-controlled trial. Exp Opin Biol Ther. 2023;23(8):705-15.[CrossRef]

29. Berlec A, Štrukelj B. Current state and recent advances in biopharmaceutical production in Escherichia coli, yeasts, and mammalian cells. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2023;40(3-4):257-74.[CrossRef]

30. Joshi AK, Gupta SK. Single-use continuous manufacturing and process intensification for the production of affordable biological drugs. Process Control Intensif Digit Cont Biomanuf. 2022;14:179-208. [CrossRef]

31. Yang J, Yu S, Yang Z, Yan Y, Chen Y, Zeng H, et al. Efficacy and safety of anti-cancer biosimilar compared to reference biologics in oncology:A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Bio Drugs. 2019;33(4):357-71.[CrossRef]

32. Vemula GK, Badale P, Mavrogenis P, Lalande-Luesink I, Borkowski M, Lewis DJ. A Risk-Based approach for safety case Follow-up of adverse event reports in pharmacovigilance. Adv Ther. 2024;41(1):82-91.[CrossRef]

33. Wilsdon T, Pistollato M, Ross-Stewart K, Saada R, Barquin P, AlnaqbixKA, et al. Biosimilars:A global roadmap for policy sustainability. Charles River Associates. Washington, DC;2022. 1.

34. Bas TG, Duarte V. Biosimilar in the era of artificial intelligence-international regulations and the use in oncological treatments. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024;17(7):925.[CrossRef]

35. Ahmad AS, Olech E, McClellan JE, Kirchhoff CF. Development of biosimilar. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016;45(5 Suppl):S11-8.[CrossRef]

36. Gimpel AL, Katsikis G, Sha S, Maloney AJ, Hong MS, Nguyen TN, Wolfrum J, Springs SL, Sinskey AJ, Manalis SR, Barone PW. Analytical methods for process and product characterization of recombinant adeno-associated virus-based gene therapies. Molecular Therapy Methods &Clinical Development 2021;20:740-54.[CrossRef]

37. Kirchhoff CF, Wang XZ, Conlon HD, Anderson S, Ryan AM, Bose A. Biosimilar:Key regulatory considerations and similarity assessment tools. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2017;114(12):2696-705.[CrossRef]

38. Schreitmüller T, Barton B, Zharkov A, Bakalos G. Comparative immunogenicity assessment of biosimilar. Future Oncol. 2018;15(3):319-29.[CrossRef]

39. Meunier S, De Bourayne M, Hamze M, Azam A, Correia E, Menier C, et al. Specificity of the T cell response to protein biopharmaceuticals. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1550.[CrossRef]

40. Budzinski K, Constable D, D'Aquila D, Smith P, Madabhushi SR, Whiting A, et al. Streamlined life cycle assessment of single use technologies in biopharmaceutical manufacture. New Biotechnol. 2022;68:28-36.[CrossRef]

41. Pietrzykowski M, Flanagan W, Pizzi V, Brown A, Sinclair A, Monge M. An environmental life cycle assessment comparison of single-use and conventional process technology for the production of monoclonal antibodies. J Clean Prod. 2013;41:150-62. [CrossRef]

42. Prior S, Metcalfe C, Hufton SE, Wadhwa M, Schneider CK, Burns C. Maintaining 'standards'for biosimilar monoclonal antibodies. Nat Biotechnol. 2021;39(3):276-80. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-021-00848-0[CrossRef]

43. Andrade AM, da Motta Girardi J, da Silva ET, Barbosa JR, Pereira DC. Efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of biosimilar compared with the biologic etanercept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis:A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2024;13(1):291.[CrossRef]

44. Bitoun S, Hässler S, Ternant D, Szely N, Gleizes A, Richez C, et al. Response to biologic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and antidrug antibodies. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):2323098. [CrossRef]

45. Bellinvia S, Edwards CJ. Explaining biosimilar and how reverse engineering plays a critical role in their development. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2020;15(11):1283-9.[CrossRef]

46. Gonçalves J, Araújo F, Cutolo M, Fonseca JE. Biosimilar monoclonal antibodies:Preclinical and clinical development aspects. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34(4):698-705.

47. Adami G, Saag KG, Chapurlat RD, Guañabens N, Haugeberg G, Lems WF, et al. Balancing benefits and risks in the era of biologics. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2019;11:1759720X19883973.[CrossRef]

48. Gherghescu I, Delgado-Charro MB. The biosimilar landscape:An overview of regulatory approvals by the EMA and FDA. Pharmaceutics. 2020;13(1):48.[CrossRef]

49. Mascarenhas-Melo F, Diaz M, Gonçalves MB, Vieira P, Bell V, Viana S, et al. An overview of biosimilar development, quality, regulatory issues, and management in healthcare. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024;17(2):235. [CrossRef]

50. Halimi V, Daci A, Ancevska Netkovska K, Suturkova L, Babar ZU, Grozdanova A. Clinical and regulatory concerns of biosimilar:A review of literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5800. [CrossRef]

51. Alvarez DF, Wolbink G, Cronenberger C, Orazem J, Kay J. Interchangeability of biosimilars:What level of clinical evidence is needed to support the interchangeability designation in the United States?Bio Drugs. 2020;34(6):723. [CrossRef]

52. Uozumi R, Hamada C. Adaptive seamless design for establishing pharmacokinetic and efficacy equivalence in developing biosimilar. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2017;51(6):761-9.[CrossRef]

53. Bujkiewicz S, Singh J, Wheaton L, Jenkins D, Martina R, Hyrich KL, et al. Bridging disconnected networks of first and second lines of biologic therapies in rheumatoid arthritis with registry data:Bayesian evidence synthesis with target trial emulation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2022;150:171-8.[CrossRef]

54. Al Meslamani AZ. Short and long-term economic implications of biosimilar. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2024;24(7):567-70.[CrossRef]

55. Mielke J, Innerbichler F, Schiestl M, Ballarini NM, Jones B. The assessment of quality attributes for biosimilar:A statistical perspective on current practice and a proposal. AAPS J. 2019;21:7.[CrossRef]

56. Dash R, Singh SK, Chirmule N, Rathore AS. Assessment of functional characterization and comparability of bio therapeutics:A review. AAPS J. 2022;24:15.[CrossRef]

57. Stangler T, Schiestl M. Similarity assessment of quality attributes of biological medicines:The calculation of operating characteristics to compare different statistical approaches. AAPS Open. 2019;5(1):1-6.[CrossRef]

58. Kwon O, Joung J, Park Y, Kim CW, Hong SH. Considerations of critical quality attributes in the analytical comparability assessment of biosimilar products. Biologicals. 2017;48:101-8.[CrossRef]

59. Vashishat A, Patel P, Das Gupta G, Das Kurmi B. Alternatives of animal models for biomedical research:A comprehensive review of modern approaches. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2024;20(4):881-99.[CrossRef]

60. Van Norman GA. Limitations of animal studies for predicting toxicity in clinical trials:Part 2:Potential alternatives to the use of animals in preclinical trials. Basic Transl Sci. 2020;5(4):387-97.[CrossRef]

61. Guideline IH. Preclinical safety evaluation of biotechnology-derived pharmaceuticals S6 (R1). In:Proceedings of the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use;2011. https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/S6_R1_Guideline_0.pdf

62. Niazi SK. Biosimilar:Harmonizing the approval guidelines. Biologics. 2022;2(3):171-95.[CrossRef]

63. McGrath LN, Moodie D, Feldman SR. Biologics and biosimilar in musculoskeletal diseases:Addressing regulatory inconsistencies and clinical uncertainty. Explor Musculoskelet Dis. 2025;3:100798.[CrossRef]

64. Shibata H, Harazono A, Kiyoshi M, Saito Y, Ishii-Watabe A. Characterization of biosimilar monoclonal antibodies and their reference products approved in Japan to reveal the quality characteristics in post approval phase. BioDrugs. 2025;39:645-67.[CrossRef]