REFERENCES

1. Liu C, Han R, Hu CY, Deng S, Liu X, Chen Y, et al. Biogeochemical pathways of phytate-P utilization in soil:plant and microbial strategies. Environ Sci Technol. 2025;59(31):16069-89.[CrossRef]

2. Hill J, Richardson A. Isolation and assessment of microorganisms that utilize phytate. In:Turner BL, Richardson AE, Mullaney EJ, editors. Inositol Phosphates:Linking Agriculture and the Environment. Wallingford, UK:CAB International;2007. 61-77.[CrossRef]

3. Sanchis P, Buades JM, Berga F, Gelabert MM, Molina M, Íñigo MV, et al. Protective effect of myo-inositol hexaphosphate (phytate) on abdominal aortic calcification in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Ren Nutr. 2016;26(4):226-36.[CrossRef]

4. Grases F, Costa-Bauza A. Key aspects of myo-inositol hexaphosphate (phytate) and pathological calcifications. Molecules. 2019;24(24):4434.[CrossRef]

5. Liu X, Han R, Cao Y, Turner BL, Ma LQ. Enhancing phytate availability in soils and phytate-p acquisition by plants:A review. Environ Sci Technol. 2022;56(13):9196-219.[CrossRef]

6. Konietzny U, Greiner R. Molecular and catalytic properties of phytate-degrading enzymes (phytases). Int J Food Sci Technol. 2002;37(7):791-812.[CrossRef]

7. Singh B, Satyanarayana T. Fungal phytases:Characteristics and amelioration of nutritional quality and growth of non-ruminants. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). 2015;99(4):646-60.[CrossRef]

8. Rizwanuddin S, Kumar V, Singh P, Naik B, Mishra S, Chauhan M, et al. Insight into phytase-producing microorganisms for phytate solubilization and soil sustainability. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1127249.[CrossRef]

9. Jatuwong K, Suwannarach N, Kumla J, Penkhrue W, Kakumyan P, Lumyong S. Bioprocess for production, characteristics, and biotechnological applications of fungal phytases. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:188.[CrossRef]

10. Dailin DJ, Hanapi SZ, Elsayed EA, Sukmawati D, Azelee NI, Eyahmalay J, et al. Fungal phytases:Biotechnological applications in food &feed industries. In:Yadav AN, Singh S, Mishra S, Gupta A, editors. Recent Advances in White Biotechnology through Fungi. Cham:Springer;2019. 65-99.[CrossRef]

11. Berendsen RL, Pieterse CM, Bakker PA. The rhizosphere microbiome and plant health. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17:478-86.[CrossRef]

12. Bhadrecha P, Singh S, Dwibedi V. 'A plant's major strength in rhizosphere':The plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. Arch Microbiol. 2023;205:165.[CrossRef]

13. Andrade LA, Santos CHB, Frezarin ET, Sales LR, Rigobelo EC. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria for sustainable agricultural production. Microorganisms. 2023;11:1088.[CrossRef]

14. Singh B, Boukhris I, Kumar V, Yadav AN, Farhat-Khemakhem A, Kumar A, et al. Contribution of microbial phytases to the improvement of plant growth and nutrition:A review. Pedosphere. 2020;30(3):295-313.[CrossRef]

15. Li Q, Yang X, Li J, Li M, Li C, Yao T. In-depth characterization of phytase-producing plant growth promotion bacteria isolated in alpine grassland of Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Front Microbiol. 2023;13:1019383.[CrossRef]

16. Ghorbani Nasrabadi R, Greiner R, Mayer-Miebach E, Menezes-Blackburn D. Phosphate solubilizing and phytate degrading Streptomyces isolates stimulate the growth and P accumulation of maize (Zea mays) fertilized with different phosphorus sources. Geomicrobiol J. 2023;40(4):325-36.[CrossRef]

17. Ghoreshizadeh S, Calvo-Peña C, Ruiz-Muñoz M, Otero-Suárez R, Coque JJ, Cobos R. Pseudomonas taetrolens ULE-PH5 and Pseudomonas sp. ULE-PH6 isolated from the hop rhizosphere increase phosphate assimilation by the plant. Plants. 2024;13(3):402.[CrossRef]

18. Carmen Orozco-Mosqueda M, Santoyo G. Plant-microbial endophytes interactions:Scrutinizing their beneficial mechanisms from genomic explorations. Curr Plant Biol. 2021;25:100189.[CrossRef]

19. Rehman A, Farooq M, Naveed M, Nawaz A, Shahzad B. Seed priming of Zn with endophytic bacteria improves the productivity and grain biofortification of bread wheat. Eur J Agron. 2018;94:98-107.[CrossRef]

20. Yue Z, Shen Y, Chen Y, Liang A, Chu C, Chen C, et al. Microbiological insights into the stress-alleviating property of an endophytic Bacillus altitudinis WR10 in wheat under low-phosphorus and high-salinity stresses. Microorganisms. 2019;7(11):508.[CrossRef]

21. Zhu A, Tan H, Cao L. Isolation of phytase-producing yeasts from rice seedlings for prospective probiotic applications. 3 Biotech. 2019;9:216.[CrossRef]

22. Li GE, Kong WL, Wu XQ, Ma SB. Phytase-producing Rahnella aquatilis JZ-GX1 promotes seed germination and growth in corn (Zea mays L.). Microorganisms. 2021;9(8):1647.[CrossRef]

23. Verma S, Kumar M, Kumar A, Das S, Chakdar H, Varma A, et al. Diversity of bacterial endophytes of maize (Zea mays) and their functional potential for micronutrient biofortification. Curr Microbiol. 2021;79(1):6.[CrossRef]

24. Bashir I, War AF, Rafiq I, Reshi ZA, Rashid I, Shouche YS. Phyllosphere microbiome:Diversity and functions. Microbiol Res. 2022;254:126888.[CrossRef]

25. Rossmann M, Sarango-Flores SW, Chiaramonte JB, Kmit MC, Mendes R. Plant microbiome:Composition and functions in plant compartments. In:Pylro V, Roesch L, editors. The Brazilian Microbiome. Cham:Springer;2017. 7-20.[CrossRef]

26. Gandolfi I, Canedoli C, Imperato V, Tagliaferri I, Gkorezis P, Vangronsveld J, et al. Diversity and hydrocarbon-degrading potential of epiphytic microbial communities on Platanus x acerifolia leaves in an urban area. Environ Pollut. 2017;220:650-8.[CrossRef]

27. Rocky-Salimi K, Hashemi M, Safari M, Mousivand M. A novel phytase characterized by thermostability and high pH tolerance from rice phyllosphere isolated Bacillus subtilis B.S.46. J Adv Res. 2016;7(3):381-90.[CrossRef]

28. Smyth EM, McCarthy J, Nevin R, Khan MR, Dow JM, O'gara F, et al. In vitro analyses are not reliable predictors of the plant growth promotion capability of bacteria;a Pseudomonas fluorescens strain that promotes the growth and yield of wheat. J Appl Microbiol. 2011;111(3):683-92.[CrossRef]

29. Amoozegar MA, Safarpour A, Noghabi KA, Bakhtiary T, Ventosa A. Halophiles and their vast potential in biofuel production. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1895.[CrossRef]

30. Dion P. Extreme views on prokaryote evolution. In:Dion P, Nautiyal CS, editors. Microbiology of Extreme Soils. Berlin:Springer;2008. 45-70.[CrossRef]

31. Gayatri Dave GD, Hasmukh Modi HM. Phytase producing microbial species associated with rhizosphere of mangroves in an Arid Coastal Region of Dholara. Acad J Biotechnol. 2013;1(2):27-35.

32. Patki JM, Singh S, Mehta S. Partial purification and characterization of phytase from bacteria inhabiting the mangroves of the western coast of India. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2015;4(9):156-69.

33. Zhu F, Qu L, Hong X, Sun X. Isolation and characterization of a phosphate-solubilizing halophilic bacterium Kushneriasp. YCWA18 from Daqiao Saltern on the coast of Yellow Sea of China. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:615032.[CrossRef]

34. Pati B, Padhi S. Isolation and characterization of phosphate solubilizing bacteria in saline soil from Costal Region of Odisha. GSC Biol Pharm Sci. 2021;16(3):109-19.[CrossRef]

35. Mussa ES, Al-Sharnouby SF, Ramadan AI, Ismael WH. Exploring halotolerant phosphate-solubilizing bacteria isolated from mangrove soil for agricultural and ecological benefits. Asian Soil Res J. 2024;8(4):124-41. [CrossRef]

36. Boyadzhieva I, Berberov K, Atanasova N, Krumov N, Kabaivanova L. Isolation, purification and in vitro characterization of a newly isolated alkalophilic phytase produced by the halophile cobetia marina strain 439 for use as animal food supplement. Fermentation. 2025;11(1):39.[CrossRef]

37. Stout LM, Nguyen TT, Jaisi DP. Relationship of phytate, phytate-mineralizing bacteria, and beta-propeller phytase genes along a coastal tributary to the Chesapeake Bay. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 2016;80(1):84-96. [CrossRef]

38. Farha AK, Hatha AM. Bioprospecting potential and secondary metabolite profile of a novel sediment-derived fungus Penicillium sp. ArCSPf from continental slope of Eastern Arabian Sea. Mycology. 2019;10(2):109-17. [CrossRef]

39. Saranya K, Sundaramanickam A, Manupoori S, Kanth SV. Screening of multi-faceted phosphate-solubilising bacterium from seagrass meadow and their plant growth promotion under saline stress condition. Microbiol Res. 2022;261:127080.[CrossRef]

40. Singh B, Satyanarayana T. Phytases and phosphatases of thermophilic microbes:Production, characteristics and multifarious biotechnological applications. In:Satyanarayana T, Littlechild J, Kawarabayasi Y, editors. Thermophilic Microbes in Environmental and Industrial Biotechnology. Netherlands:Springer;2013. 671-87.[CrossRef]

41. Singh B, Satyanarayana T. Phytases from thermophilic molds:Their production, characteristics and multifarious applications. Process Biochem. 2011;46(7):1391-8.[CrossRef]

42. Rebello S, Jose L, Sindhu R, Aneesh EM. Molecular advancements in the development of thermostable phytases. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101(7):2677-89.[CrossRef]

43. Nampoothiri KM, Tomes GJ, Roopesh K, Szakacs G, Nagy V, Soccol CR, et al. Thermostable phytase production by Thermoascus aurantiacus in submerged fermentation. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2004;118:205-14 [CrossRef]

44. Yu P, Chen Y. Purification and characterization of a novel neutral and heat-tolerant phytase from a newly isolated strain Bacillus nealsonii ZJ0702. BMC Biotechnol. 2013;13(1):78.[CrossRef]

45. Parhamfar M, Badoei-Dalfard A, Khaleghi M, Hassanshahian M. Purification and characterization of an acidic, thermophilic phytase from a newly isolated Geobacillus stearothermophilus strain DM12. Prog Biol Sci. 2015;5(1):61-73.

46. Zhang Z, Yang J, Xie P, Gao Y, Bai J, Zhang C, et al. Characterization of a thermostable phytase from Bacillus licheniformis WHU and further stabilization of the enzyme through disulfide bond engineering. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2020;142:109679.[CrossRef]

47. Puppala KR, Bhavsar K, Sonalkar V, Khire JM, Dharne MS. Characterization of novel acidic and thermostable phytase secreting Streptomyces sp. (NCIM 5533) for plant growth promoting characteristics. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2019;18:101020.[CrossRef]

48. Rizvi A, Ahmed B, Khan MS, Umar S, Lee J. Psychrophilic bacterial phosphate-biofertilizers:A novel extremophile for sustainable crop production under cold environment. Microorganisms. 2021;9(12):2451.[CrossRef]

49. Kumar V, Singh P, Jorquera MA, Sangwan P, Kumar P, Verma AK, et al. Isolation of phytase-producing bacteria from Himalayan soils and their effect on growth and phosphorus uptake of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea). World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;29(8):1361-9.[CrossRef]

50. Pal Roy M, Datta S, Ghosh S. A novel extracellular low-temperature active phytase from Bacillus aryabhattai RS1 with potential application in plant growth. Biotechnol Prog. 2017;33(3):633-41.[CrossRef]

51. Wan W, Qin Y, Wu H, Zuo W, He H, Tan J, et al. Isolation and characterization of phosphorus solubilizing bacteria with multiple phosphorus sources utilizing capability and their potential for lead immobilization in soil. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:752.[CrossRef]

52. Adhikari P, Jain R, Sharma A, Pandey A. Plant growth promotion at low temperature by phosphate-solubilizing PseudomonasSpp. from high-altitude Himalayan soil. Microb Ecol. 2021;82(3):677-87. [CrossRef]

53. Thapa S, Li H, OHair J, Bhatti S, Chen FC, Nasr KA, et al. Biochemical characteristics of microbial enzymes and their significance from industrial perspectives. Mol Biotechnol. 2019;61(8):579-601.[CrossRef]

54. Oh BC, Choi WC, Park S, Kim YO, Oh TK. Biochemical properties and substrate specificities of alkaline and histidine acid phytases. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;63(4):362-72.[CrossRef]

55. Oliveira Ornela PH, Guimarães LH. Purification and characterization of an alkalistable phytase produced by Rhizopus microsporus var. microsporus in submerged fermentation. Process Biochem. 2019;81:70-6.[CrossRef]

56. Zhang R, Yang P, Huang H, Yuan T, Shi P, Meng K, et al. Molecular and biochemical characterization of a new alkaline b-propeller phytase from the insect symbiotic bacterium Janthinobacterium sp. TN115. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;92(2):317-25.[CrossRef]

57. Zhang R, Yang P, Huang H, Shi P, Yuan T, Yao B. Two types of phytases (histidine acid phytase and b-propeller phytase) in Serratiasp. TN49 from the gut of Batocera horsfieldi (Coleoptera) larvae. Curr Microbiol. 2011;63:408-15.[CrossRef]

58. Soni SK, Magdum A, Khire JM. Purification and characterization of two distinct acidic phytases with broad pH stability from Aspergillus niger NCIM 563. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;26(11):2009-18.[CrossRef]

59. Tan H, Mooij MJ, Barret M, Hegarty PM, Harrington C, Dobson AD, et al. Purification and characterization of a novel extracellular alkaline phytase from Aeromonas sp. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;15(4):745-8. [CrossRef]

60. Kumar V, Yadav AN, Verma P, Sangwan P, Saxena A, Kumar K, et al. -Propeller phytases:Diversity, catalytic attributes, current developments and potential biotechnological applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;98:595-609. [CrossRef]

61. Trivedi S, Husain I, Sharma A. Purification and characterization of phytase from Bacillus subtilis P6:Evaluation for probiotic potential for possible application in animal feed. Food Front. 2022;3(1):194-205.[CrossRef]

62. Molina DC, Poisson GN, Kronberg F, Galvagno MA. Valorization of an Andean crop (yacon) through the production of a yeast cell-bound phytase. Biocat Agric Biotechnol. 2021;36:102116.[CrossRef]

63. Bhavsar K, Khire JM. Current research and future perspectives of phytase bioprocessing. RSC Adv. 2014;4(51):26677-91.[CrossRef]

64. Casey A, Walsh G. Identification and characterization of a phytase of potential commercial interest. J Biotechnol. 2004;110(3):313-22.[CrossRef]

65. Rao DE, Rao KV, Reddy TP, Reddy VD. Molecular characterization, physicochemical properties, known and potential applications of phytases:An overview. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2009;29(2):182-98.[CrossRef]

66. Singh P, Kumar V, Agrawal S. Evaluation of phytase producing bacteria for their plant growth promoting activities. Int J Microbiol. 2014;2014(1):426483.[CrossRef]

67. Hou X, Shen Z, Li N, Kong X, Sheng K, Wang J, et al. A novel fungal beta-propeller phytase from nematophagous Arthrobotrys oligospora:Characterization and potential application in phosphorus and mineral release for feed processing. Microb Cell Fact. 2020;19:84.[CrossRef]

68. Ferreira RC, Tavares MP, Morgan T, da Silva Clevelares Y, Rodrigues MQ, Kasuya MC, et al. Genome-scale characterization of fungal phytases and a comparative study between beta-propeller phytases and histidine acid phosphatases. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2020;192:296-312.[CrossRef]

69. Fu D, Li Z, Huang H, Yuan T, Shi P, Luo H, et al. Catalytic efficiency of HAP phytases is determined by a key residue in close proximity to the active site. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;90:1295-302.[CrossRef]

70. Soni SK, Khire JM. Production and partial characterization of two types of phytase from Aspergillus niger NCIM 563 under submerged fermentation conditions. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;23:1585-93.[CrossRef]

71. Wang Y, Wang L, Zhang J, Duan X, Feng Y, Wang S, et al. PA0335, a gene encoding histidinol phosphate phosphatase, mediates histidine auxotrophy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2020;86(5):02593-19.[CrossRef]

72. Suleimanova A, Bulmakova D, Sharipova M. Heterologous expression of histidine acid phytase from Pantoea sp. 3.5. 1 in methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris. Open Microbiol J. 2020;14:179-89. [CrossRef]

73. Ghahremani M, Plaxton WC. Phosphoprotein phosphatase function of secreted purple acid phosphatases. In:Pandey GK, editor. Protein Phosphatases and Stress Management in Plants. Cham:Springer;2020. 11-28. [CrossRef]

74. Mehra P, Giri J. Purple acid phosphatases (PAPs):Molecular regulation and diverse physiological roles in plants. In:Pandey GK, editor. Protein Phosphatases and Stress Management in Plants. Cham:Springer;2020. 29-51. [CrossRef]

75. Srivastava R, Parida AP, Chauhan PK, Kumar R. Identification, structure analysis, and transcript profiling of purple acid phosphatases under Pi deficiency in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) its wild relatives. Inter J Biol Macromol. 2020;165:2253-66.[CrossRef]

76. Merkx M, Averill BA. The activity of oxidized bovine spleen purple acid phosphatase is due to an Fe (III) Zn (II)'impurity'. Biochemistry. 1998;37(32):11223-31.[CrossRef]

77. Funhoff EG, Bollen M, Averill BA. The Fe (III) Zn (II) form of recombinant human purple acid phosphatase is not activated by proteolysis. J Inorg Biochem. 2005;99(2):521-9.[CrossRef]

78. Del Vecchio HA. Biochemical and Molecular Characterization of AtPAP25, a Novel Cell Wall-Localized Purple Acid Phosphatase Isozyme Upregulated by Phosphate-Starved Arabidopsis thaliana. Canada:Queen's University;2012.

79. Tran HT, Hurley BA, Plaxton WC. Feeding hungry plants:The role of purple acid phosphatases in phosphate nutrition. Plant Sci. 2010;179(1-2):14-27.[CrossRef]

80. Mukhametzyanova AD, Akhmetova AI, Sharipova MR. Microorganisms as phytase producers. Microbiology. 2012;81:267-75.[CrossRef]

81. Rezende Graminho E. Purification and characterization of the phytase produced by Burkholderia sp. a13 isolated from the aquatic environment. 2015, Ph.D thesis, University of Tsukuba, 146.

82. Yee PC, Chin SC, Chin YB, Vui LC, Abdullah N, Radu S, et al. Cloning of a novel phytase from an anaerobic rumen bacterium, Mitsuokella jalaludinii, and its expression in Escherichia coli. J Integr Agric. 2015;14(9):1816-26. [CrossRef]

83. Corrêa TL, de Araújo EF. Fungal phytases:From genes to applications. Braz J Microbiol. 2020;51(3):1009-20.[CrossRef]

84. Greppi A, Krych ?, Costantini A, Rantsiou K, Hounhouigan DJ, Arneborg N, et al. Phytase-producing capacity of yeasts isolated from traditional African fermented food products and PHYPk gene expression of Pichia kudriavzevii strains. Int J Food Microbiol. 2015;205:81-9.[CrossRef]

85. Herrera-Estala AL, Fuentes-Garibay JA, Guerrero-Olazarán M, Viader-SalvadóJM. Low specific growth rate and temperature in fed-batch cultures of a beta-propeller phytase producing Pichia pastoris strain under GAP promoter trigger increased KAR2 and PSA1-1 gene expression yielding enhanced extracellular productivity. J Biotechnol. 2022;352:59-67.[CrossRef]

86. Nezhad NG, Rahman RN, Normi YM, Oslan SN, Shariff FM, Leow TC. Isolation, screening and molecular characterization of phytase-producing microorganisms to discover the novel phytase. Biologia. 2023;78(9):2527-37. [CrossRef]

87. Ariza A, Moroz OV, Blagova EV, Turkenburg JP, Waterman J, Roberts SM, et al. Degradation of phytate by the 6-phytase from Hafnia alvei:A combined structural and solution study. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):65062.[CrossRef]

88. Yao MZ, Zhang YH, Lu WL, Hu MQ, Wang W, Liang AH. Phytases:Crystal structures, protein engineering and potential biotechnological applications. J Appl Microbiol. 2012;112(1):1-14.[CrossRef]

89. Cangussu AS, Aires Almeida D, Aguiar RW, Bordignon-Junior SE, Viana KF, Barbosa LC, et al. Characterization of the catalytic structure of plant phytase, protein tyrosine phosphatase-like phytase, and histidine acid phytases and their biotechnological applications. Enzyme Res. 2018;2018(1):240698.[CrossRef]

90. Ushasree MV, Shyam K, Vidya J, Pandey A. Microbial phytase:Impact of advances in genetic engineering in revolutionizing its properties and applications. Bioresour Technol. 2017;245:1790-9.[CrossRef]

91. Balwani I, Chakravarty K, Gaur S. Role of phytase producing microorganisms towards agricultural sustainability. Biocat Agric Biotechnol. 2017;12:23-9.[CrossRef]

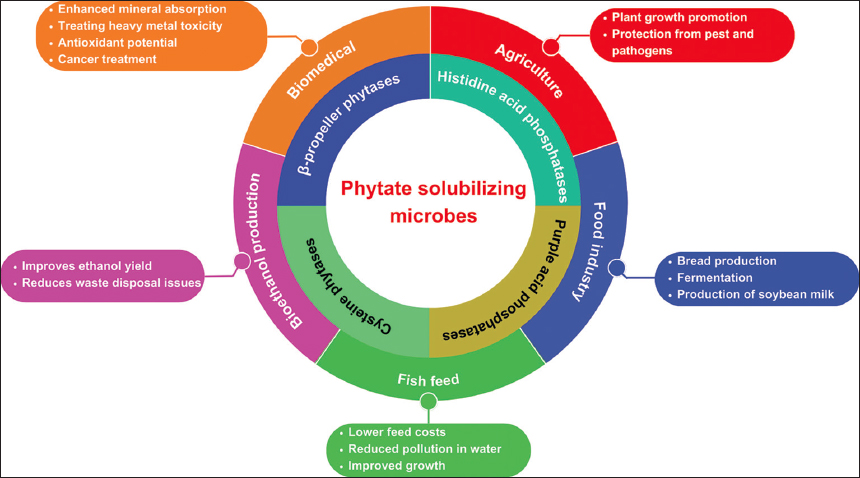

92. Handa V, Sharma D, Kaur A, Arya SK. Biotechnological applications of microbial phytase and phytic acid in food and feed industries. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2020;25:101600.[CrossRef]

93. Kaur G. Microbial phytases in plant minerals acquisition. In:Sharma V, Salwan R, Al-Ani LKT, editors. Molecular Aspects of Plant Beneficial Microbes in Agriculture. Cambridge:Academic Press;2020. 185-94.[CrossRef]

94. Mazid M, Khan TA. Khan, Future of bio-fertilizers in Indian agriculture:An overview. Int J Agric Food Res. 2015;3(3):10-23.[CrossRef]

95. Bagyaraj DJ, Rangaswami G. Agricultural Microbiology. New Delhi:PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd.;2007.

96. Kaur R, Kaur S. Exploration of phytate-mineralizing bacteria with multifarious plant growth-promoting traits. BioTechnologia (Pozn). 2022;103(2):99-112.[CrossRef]

97. Yi Y, Li Z, Song C, Kuipers OP. Exploring plant-microbe interactions of the rhizobacteria Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus mycoides by use of the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Environ Microbiol. 2018;20(12):4245-60.[CrossRef]

98. Joudaki H, Aria N, Moravej R, Yazdi MR, Emami-Karvani Z, Hamblin MR. Microbial phytases:Properties and applications in the food industry. Curr Microbiol. 2023;80(12):374.[CrossRef]

99. El Ifa W, Belgaroui N, Sayahi N, Ghazala I, Hanin M. Phytase-producing rhizobacteria enhance barley growth and phosphate nutrition. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2024;8:1432599. [CrossRef]

100. Suleimanova A, Bulmakova D, Sokolnikova L, Egorova E, Itkina D, Kuzminova O, et al. Phosphate solubilization and plant growth promotion by Pantoea brenneri soil isolates. Microorganisms. 2023;11(5):1136.[CrossRef]

101. Mei C, Chretien RL, Amaradasa BS, He Y, Turner A, Lowman S. Characterization of phosphate solubilizing bacterial endophytes and plant growth promotion in vitroand in greenhouse. Microorganisms. 2021;9(9):1935. [CrossRef]

102. Morales-Cedeño LR, del Carmen Orozco-Mosqueda M, Loeza-Lara PD, Parra-Cota FI, de Los Santos-Villalobos S, Santoyo G. Plant growth-promoting bacterial endophytes as biocontrol agents of pre- and post-harvest diseases:Fundamentals, methods of application and future perspectives. Microbiol Res. 2021;242:126612.[CrossRef]

103. Berg G. Diversity of antifungal and plant-associated Serratia plymuthica strains. J Appl Microbiol. 2000;88(6):952-60.[CrossRef]

104. Kamensky M, Ovadis M, Chet I, Chernin L. Soil-borne strain IC14 of Serratia plymuthica with multiple mechanisms of antifungal activity provides biocontrol of Botrytis cinerea and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum diseases. Soil Biol Biochem. 2003;35(2):323-31.[CrossRef]

105. Ovadis M, Liu X, Gavriel S, Ismailov Z, Chet I, Chernin L. The global regulator genes from biocontrol strain Serratia plymuthica IC1270:Cloning, sequencing, and functional studies. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(15):4986-93. [CrossRef]

106. Xue Y, Zhang Y, Huang K, Wang X, Xing M, Xu Q, et al. A novel biocontrol agent Bacillus velezensis K01 for management of gray mold caused by Botrytis cinerea. AMB Expr. 2023;13(1):91.[CrossRef]

107. Correll DL. Phosphorus:A rate limiting nutrient in surface waters. Poult Sci. 1999;78(5):674-82.[CrossRef]

108. Cao L, Wang W, Yang C, Yang Y, Diana J, Yakupitiyage A, et al. Application of microbial phytase in fish feed. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2007;40(4):497-507.[CrossRef]

109. Caipang C, Dechavez RB, Amar MJ. Potential application of microbial phytase in aquaculture. ELBA Bioflux. 2011;3(1):55-66.

110. Omogbenigun FO, Nyachoti CM, Slominski BA. The effect of supplementing microbial phytase and organic acids to a corn-soybean based diet fed to early-weaned pigs. J Anim Sci. 2003;81(7):1806-13.[CrossRef]

111. Li MH, Robinson EH. Microbial phytase can replace inorganic phosphorus supplements in channel catfish Ictalurus punctatus diets 1. J World Aquac Soc. 1997;28(4):402-6.[CrossRef]

112. Dipesh Debnath DD, Sahu NP, Pal AK, Kartik Baruah KB, Sona Yengkokpam SY, Mukherjee SC. Present scenario and future prospects of phytase in aquafeed-Review. Asian Australas J Anim Sci. 2005;18(12):1800-12.[CrossRef]

113. Vucenik I, Shamsuddin AM. Cancer inhibition by inositol hexaphosphate (IP6) and inositol:From laboratory to clinic. J Nutr. 2003;133(11):3778S-4.[CrossRef]

114. Irshad M, Asgher M, Bhatti KH, Zafar M, Anwar Z. Anticancer and nutraceutical potentialities of phytase/phytate. Int J Pharmacol. 2017;13(7):808-17.[CrossRef]

115. Kananykhina O, Turpurova T. Phytase as a factor in phosphorus absorption. Grain Prod Mixed Fodders. 2025;25(2):19.[CrossRef]

116. Greiner R, Konietzny U. Konietzny, phytase for food application. Food Technol Biotechnol. 2006;44(2):125-40.

117. Park YJ, Park J, Park KH, Oh BC, Auh JH. Supplementation of alkaline phytase (Ds11) in whole-wheat bread reduces phytate content and improves mineral solubility. J Food Sci. 2011;76(6):C791-4.[CrossRef]

118. Porres JM, Etcheverry P, Miller DD, Lei XG. Phytase and citric acid supplementation in whole-wheat bread improves phytate-phosphorus release and iron dialyzability. J Food Sci. 2001;66(4):614-9.[CrossRef]

119. Palacios MC, Haros M, Sanz Y, Rosell CM. Phytate degradation by Bifidobacterium on whole wheat fermentation. Eur Food ResTechnol. 2008;226:825-31.[CrossRef]

120. Jain J, Singh B. Characteristics and biotechnological applications of bacterial phytases. Proc Biochem. 2016;51(2):159-69.[CrossRef]

121. Caransa A, Simell M, Lehmussaari A, Vaara M, Vaara T. A novel enzyme application for corn wet milling. Starch Stärke. 1988;40(11):409-11.[CrossRef]

122. Vohra A, Satyanarayana T. Phytases:Microbial sources, production, purification, and potential biotechnological applications. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2003;23(1):29-60.[CrossRef]

123. Chen X, Xiao Y, Shen W, Govender A, Zhang L, Fan Y, et al. Display of phytase on the cell surface of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to degrade phytate phosphorus and improve bioethanol production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;100(5):2449-58.[CrossRef]

124. Shetty JK, Paulson B, Pepsin M, Chotani G, Dean B, Hruby M. Phytase in fuel ethanol production offers economical and environmental benefits. Int Sugar J. 2008;110(1311):160-74.

125. Kumar A, Chanderman A, Makolomakwa M, Perumal K, Singh S. Microbial production of phytases for combating environmental phosphate pollution and other diverse applications. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 2016;46(6):556-91.[CrossRef]

126. Chan GF, Gan HM, Ling HL, Rashid NA. Genome sequence of Pichia kudriavzevii M12, a potential producer of bioethanol and phytase. Eukaryotic Cell. 2012;11(10):1300-1.[CrossRef]

127. Makolomakwa M, Puri AK, Permaul K, Singh S. Thermo-acid-stable phytase-mediated enhancement of bioethanol production using Colocasia esculenta. Bioresour Technol. 2017;235:396-404.[CrossRef]

128. Eida MF, Nagaoka T, Wasaki J, Kouno K. Phytate degradation by fungi and bacteria that inhabit sawdust and coffee residue composts. Microbes Environ. 2013;28(1):71-80.[CrossRef]

129. Al Mamun A, Rahman ST, Khan S. Harnessing Phytate for Phosphorus Security:Integrating Microbial and Genetic Innovations. 2025.[CrossRef]

130. Sajidan, Wulandari R, Sari EN, Ratriyanto A, Weldekiros H, Greiner R. Phytase-producing bacteria from extreme regions in Indonesia. Braz Arch Biol Technol. 2015;58(5):711-7.[CrossRef]

131. Irwan II, Agustina L, Natsir A, Ahmad A. Isolation and characterization of phytase-producing thermophilic bacteria from Sulili Hot Springs in South Sulawesi. Sci Res J. 2017;5:2201-796.

132. Ghosh S, Goswami A, Ghosh GK, Pramanik P. Characterization of potent phytate solubilizing bacterial strains of tea garden soils as futuristic potent bio-inoculant. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2021;10(4):470-84.[CrossRef]

133. Jorquera MA, Gabler S, Inostroza NG, Acuña JJ, Campos MA, Menezes-Blackburn D, et al. Screening and characterization of phytases from bacteria isolated from Chilean hydrothermal environments. Microb Ecol. 2018;75(2):387-99.[CrossRef]

134. Gauchan DP, Pandey S, Pokhrel B, Bogati N, Thapa P, Acharya A, et al. Growth promoting role of phytase producing bacteria isolated from Bambusa tulda Roxb. rhizosphere in maize seedlings under pot conditions. J Nepal Biotech Assoc. 2023;4(1):17-26.[CrossRef]

135. Hafsan H, Nurhikmah N, Harviyanti Y, Sukmawati E, Rasdianah I, Muthiadin C, et al. The potential of endophyte bacteria isolated from Zea mays L. as phytase producers. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2018;12(3):1277-80. [CrossRef]

136. Misra S, Semwal P, Pandey DD, Mishra SK, Chauhan PS. Siderophore-producing Spinacia oleracea bacterial endophytes enhance nutrient status and vegetative growth under iron-deficit conditions. J Plant Growth Regul. 2024;43(5):1317-30.[CrossRef]

137. Sharma U, Kumari S, Sinha K, Kumar S. Isolation and molecular characterization of phytase producing actinobacteria of fruit orchard. Nucleus. 2017;60(2):187-95.[CrossRef]

138. Qu LL, Peng CL, Li SB. Isolation and screening of a phytate phosphate-solubilizing Paenibacillus sp. and its growth-promoting effect on rice seeding. J Appl Ecol. 2020;31(1):326-32.

139. Adhikari P, Pandey A. Phosphate solubilization potential of endophytic fungi isolated from Taxus wallichianaZucc. . Rhizosphere. 2019;9:2-9.[CrossRef]

140. Motamedi H, Aalivand S, Varzi HN, Mohammadi M. Screening cabbage rhizosphere as a habitat for isolation of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria. Environ Exp Biol. 2016;14(4):173-81.[CrossRef]

141. Sun X, Liu F, Jiang W, Zhang P, Zhao Z, Liu X, et al. Talaromyces purpurogenus isolated from rhizosphere soil of maize has efficient organic phosphate-mineralizing and plant growth-promoting abilities. Sustainability. 2023;15(7):5961.[CrossRef]

142. Liu L, Li A, Chen J, Su Y, Li Y, Ma S. Isolation of a phytase-producing bacterial strain from agricultural soil and its characterization and application as an effective eco-friendly phosphate solubilizing bioinoculant. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 2018;49(8):984-94.[CrossRef]

143. Mittal A, Singh G, Goyal V, Yadav A, Aneja KR, Gautam SK, et al. Isolation and biochemical characterization of acido-thermophilic extracellular phytase producing bacterial strain for potential application in poultry feed. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2011;4(4):273-82.

144. Sharma B, Shukla G. Isolation, identification, and characterization of phytase producing probiotic lactic acid bacteria from neonatal fecal samples having dephytinization activity. Food Biotechnol. 2020;34(2):151-71. [CrossRef]

145. Nuobariene L, Cizeikiene D, Gradzeviciute E, Hansen ÅS, Rasmussen SK, Juodeikiene G, et al. Phytase-active lactic acid bacteria from sourdoughs:Isolation and identification. Food Sci Technol. 2015;63(1):766-72. [CrossRef]

146. Horii S, Matsuno T, Tagomori J, Mukai M, Adhikari D, Kubo M. Isolation and identification of phytate-degrading bacteria and their contribution to phytate mineralization in soil. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 2013;59(5):353-60. [CrossRef]

147. Idriss EE, Makarewicz O, Farouk A, Rosner K, Greiner R, Bochow H, et al. Extracellular phytase activity of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB45 contributes to its plant-growth-promoting effect. Microbiology. 2002;148(7):2097-109.[CrossRef]

148. Kumar P, Dubey RC, Maheshwari DK. Bacillusstrains isolated from rhizosphere showed plant growth promoting and antagonistic activity against phytopathogens. Microbiol Res. 2012;167(8):493-9.[CrossRef]

149. Hanif MK, Hameed S, Imran A, Naqqash T, Shahid M, Van Elsas JD. Isolation and characterization of a b-propeller gene containing phosphobacterium Bacillus subtilis strain KPS-11 for growth promotion of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Front Microbiol. 2015;6:583.[CrossRef]

150. Patel KJ, Singh AK, Nareshkumar G, Archana G. Organic-acid-producing, phytate-mineralizing rhizobacteria and their effect on growth of pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan). Appl Soil Ecol. 2010;44(3):252-61.[CrossRef]

151. Chanderman A, Puri AK, Permaul K, Singh S. Production, characteristics and applications of phytase from a rhizosphere isolated Enterobactersp. ACSS. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2016;39(10):1577-87.[CrossRef]

152. Li GE, Wu XQ, Ye JR, Hou L, Zhou AD, Zhao L. Isolation and identification of phytate-degrading rhizobacteria with activity of improving growth of poplar and Masson pine. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;29(11):2181-93. [CrossRef]

153. Kumar D, Rajesh S, Balashanmugam P, Rebecca LJ, Kalaichelvan PT. Screening, optimization and application of extracellular phytase from Bacillus megaterium isolated from poultry waste. J Mod Biotechnol. 2013;2:46-52.

154. Puppala KR, Naik T, Shaik A, Dastager S, Kumar R, Khire J, et al. Evaluation of Candida tropicalis (NCIM 3321) extracellular phytase having plant growth promoting potential and process development. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2018;13:225-235.[CrossRef]

155. Adhikari P, Pandey A. Bioprospecting plant growth promoting endophytic bacteria isolated from Himalayan yew (Taxus wallichiana Zucc.). Microbiol Res. 2020;239:126536.[CrossRef]

156. Narayanan M, Suresh K, Al Obaid S, Alagarsamy P, Nguyen CK. Statistical optimized production of Phytase from Hanseniaspora guilliermondii S1 and studies on purification, homology modelling and growth promotion effect. Environ Res. 2024;252:118898.[CrossRef]