4. AN INDIAN PERSPECTIVE

India has the World’s 4th largest crop acreage, after the USA, Brazil, and Argentina. The only GM crop approved for commercial cultivation and release in India is Bt cotton. It is estimated that the Bt cotton is cultivated in >96% of the country’s cotton area, as farmers are making profits from the cultivation of Bt Cotton with increased production and export. The Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) has conducted long-term studies on the impact of Bt Cotton and found no adverse effects on soil, microflora, and animal health. The cultivation of GM crops, other than Bt Cotton, is being continuously opposed by activists and banned by the government. In 2018, the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India constituted the Field Inspection and Scientific Evaluation Committee, in the exercise of powers conferred through the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986 and Rules 1989 to examine the complaints against the unlawful cultivation of herbicide tolerant (HT) or BG-III cotton in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Gujarat, and Maharashtra. Further, this committee has been constituted at the state level and was instructed to conduct on-the-spot inspection of Brinjal (in farms and markets) to check the spread of unapproved Bt Brinjal, in 2019. However, field trials for various other GM crops, including maize, rice, wheat, sorghum, groundnut, cotton, brinjal, and mustard, are approved. The commercial cultivation of these GM crops is yet to be approved. Consumer aversion to GM food, the high expense of regulatory compliance, and issues accessing the appropriate intellectual property rights are some of the difficulties.

India has maintained a cautious stance on GM organisms (GMOs), which has implications for its agricultural policies and global biotechnology markets. India’s restrictive GMO policies limit its participation in global markets that increasingly rely on biotechnology. For instance, India’s stance has affected its ability to engage with countries that support GMOs, potentially limiting access to innovative agricultural technologies that could benefit its agricultural sector [18].

India has established a complex regulatory framework for GMOs, overseen by the Genetic Engineering Appraisal Committee (GEAC). The approval process for GMOs is stringent, often resulting in lengthy delays in commercial release. For instance, the prolonged approval process for GM Bt brinjal in 2010 led to a moratorium on its commercial cultivation [19]. There is significant public opposition to GMOs in India, driven by concerns over safety, environmental impact, and the loss of traditional farming practices. A 2016 survey indicated that a majority of Indian consumers prefer organic over GM foods [20].

4.1. Biosafety and Regulations in India

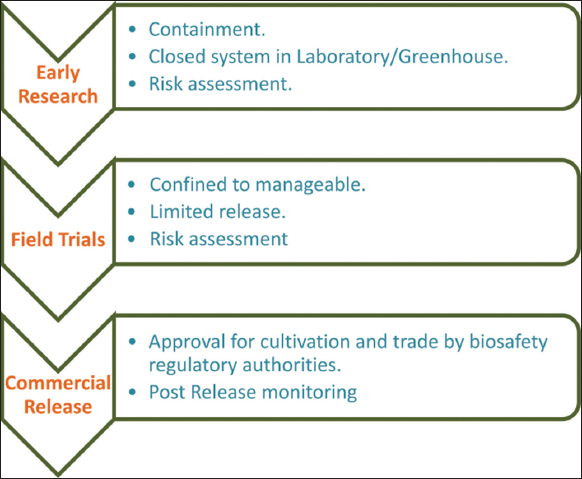

Regulations in India apply to the development, import, use, research, and release of GE organisms as well as to the goods created using these organisms are governed by the rules notified by the Ministry of Environment and Forests (Ministry of Environment, Forests [MoEF]; now the MoEF and Climate Change or MoEF&CC), Government of India, on December 5, 1989, under the Environment (Protection) Act 1986 (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). The experimental data including comparative toxicity, allergenicity, and feeding studies are required for obtaining approval from GEAC in accordance with the rules and regulations for the development, use, import, export, and storage of hazardous microorganisms, genetically engineered organisms or cells, 1989 and Revised Guidelines for Research in Transgenic Plants and Guidelines for Toxicity and Allergenicity Evaluation of Transgenic Seeds, Plants and Plant parts - 1998. These legislations and regulations, often called “Rules 1989,” regulate research as well as extensive uses of GE organisms and the products derived from them across India. The DBT, Ministry of Science and Technology, and MoEF&CC are the regulatory bodies responsible for enforcing the Rules 1989 through six competent authorities as tabulated in Table 3.

Table 3: Regulatory authorities in India.

| Sl. No. | Regulatory Authority | Role |

|---|

| 1. | Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee (RDAC) | Provides advisory functions and recommendations on biosafety guidelines. |

| 2. | Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBSC) | Approves research within an organization and ensures adherence to implementation of biosafety guidelines at organization level. |

| 3. | Review Committee on Genetic Manipulation (RCGM) | Regulates and authorizes applications for research, field experiments, and imports. |

| 4. | Genetic Engineering Appraisal Committee (GEAC) | Key authority that approves the large-scale use and experimental/commercial release of GMOs in the environment. |

| 5. | State Biotechnology Coordination Committee (SBCC) | Monitors and coordinates GMO-related activities at the state level. |

| 6. | District Level Committee (DLC) | Monitors safety regulations and GMO-related activities and installations at the district level. |

To protect the interests of farmers and environmentalists, the Government of India has very strict guidelines for testing and evaluating the agronomic value of GM crops. The guidelines are drafted to address all biosafety concerns related to GM crops. Still, India has gone through several setbacks with GM technology in crops. In 2005, ICAR launched a “Network Project on Transgenic in Crops” (presently as “Network Project on Functional Genomics and Genetic Modification in Crops”) to promote the innovation and development of GM Crops. Pigeon pea, chickpea, sorghum, potato, brinjal, tomato and banana are in different stages of development and case-by-case testing. In 2012, the Parliamentary Committee on Agriculture asked the Indian Government to discontinue field trials and ban GM crops. The committee stated that there are insignificant socio-economic benefits to farmers and raised issues such as ethical dimensions of transgenics and long-term impact on health and the environment. Notably, the National Institution for Transforming India Aayog released a statement in 2016, “As a part of its strategy to bring a Second Green Revolution, India must return to permitting proven and well tested GM technologies with adequate safeguards.” This statement supports allowing GM crops in agriculture.

On August 25, 2017, the Parliamentary Standing Committee submitted its report to Parliament on “Genetically modified crops and its impact on the environment” recommending the introduction of GM crops after critical scientific evaluation for benefits and biosafety, and restructuring of the regulatory framework for unbiased assessment of GM crops. As per the advice of GEAC, the safety assessment data for the GM mustard (Dhara Mustard Hybrid 11; DMH11) has been generated. Biosafety Research Level I (BRL I) field trial for two new transgenic indigenous Bt Brinjal varieties was conducted in three locations, Jalna, Guntur, and Varanasi, in 2009–2010. In 2020, the GEAC allowed biosafety research (BRL II) field trials of Bt Brinjal in eight states (Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha, and West Bengal) during 2020–2023, only after receiving NOC from the concerned states and confirming that an isolated land area is available for this purpose. The Bt Brinjal varieties, namely, Janak and BSS-793, are indigenously developed by the ICAR. It has CryFa1-Event 142 to resist attacks of fruit and shoot borer.

4.2. India Limits Global Appeal for GMO

Political dynamics play a crucial role in GMO policy. Various political parties have adopted anti-GMO stances due to public pressure and electoral considerations. For example, the current government has faced criticism for its handling of agricultural biotechnology, impacting its approach to GMOs [21]. The adoption of GMOs is feared to disproportionately benefit large agribusinesses while marginalizing smallholder farmers. Advocacy groups argue that GMOs could lead to increased dependency on multinational corporations for seeds [22]. Environmentalists argue that GMOs pose risks to biodiversity and traditional crop varieties. India’s rich agricultural diversity is considered a national asset, and there are fears that introducing GMOs could jeopardize this genetic heritage [23].

4.3. India’s 2022 Policy Shift on GM Crops

In 2022, India announced significant policy changes regarding the approval and regulation of GM crops. India’s 2022 policy shift towards embracing biotechnology in agriculture reflects a strategic government response to several pressing agricultural challenges. Concurrently, the persistence of unapproved GM crop adoption presents a complex challenge that must be addressed to ensure safe and sustainable agricultural practices moving forward. The Central Government aimed to bolster domestic agricultural productivity and food security through advancements in biotechnology. On March 30, 2022, a new rule was issued as an office memorandum by the MoEF&CC CS-III Biosafety Division to exempt the SDN1 and SDN2 genome-edited plants from biosafety assessment in accordance with the rule 20 of the Manufacture, Use, Import, Export, and Storage of Hazardous Microorganisms/Genetically engineered Organisms or Cells Rules 1989. These changes are followed by the recommendations from the DBT (Ministry of Science and Technology), and the Department of Agriculture, Research and Education (Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare). However, the process of developing genome-edited plants has to be carried out under containment, and regulated by Institutional Biosafety Committees under information to the Review Committee on Genetic Manipulation.

Despite the stringent regulatory framework, field data indicate that unapproved GM crops, particularly Bt cotton and other Varieties, have been adopted informally by a segment of Indian farmers. These illicit cultivations often arise from farmers’ perceptions of increased yields and pest resistance associated with these crops. Reports suggest that farmers have access to unofficial seeds, and their utilization can lead to significant economic benefits, although it poses risks related to biodiversity and environmental safety [24]. In certain regions, studies have documented that farmers planting unapproved GM varieties observed improved resilience to climatic stresses, further motivating their adoption despite legal risks. These trends highlight a gap between regulatory frameworks and on-the-ground practices, as farmers prioritize immediate agricultural challenges over compliance with formal regulations [25].

The policy revamp was particularly influenced by the challenges posed by climate change and the necessity for sustainable agricultural practices [26]. The government sought to promote innovation while maintaining safety protocols, ensuring that any GM crop introduced undergoes rigorous testing to assess environmental and health impacts [27]. This shift included the introduction of a more streamlined approval process for GM crops, emphasizing the need for governmental support in deploying technologies that improve crop yields and resistance to pests and diseases. This shows India’s evolving stance on GM crops and the reality of farmer behavior in the face of regulation. Safety assessment and Screening of GM crops and/or derived foods.

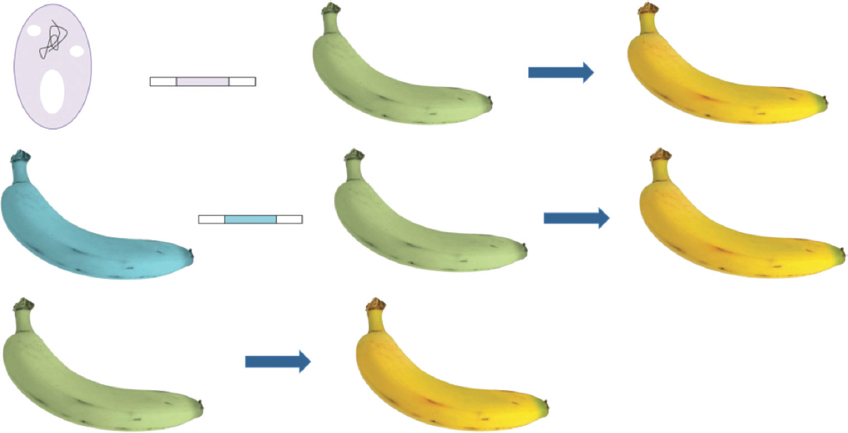

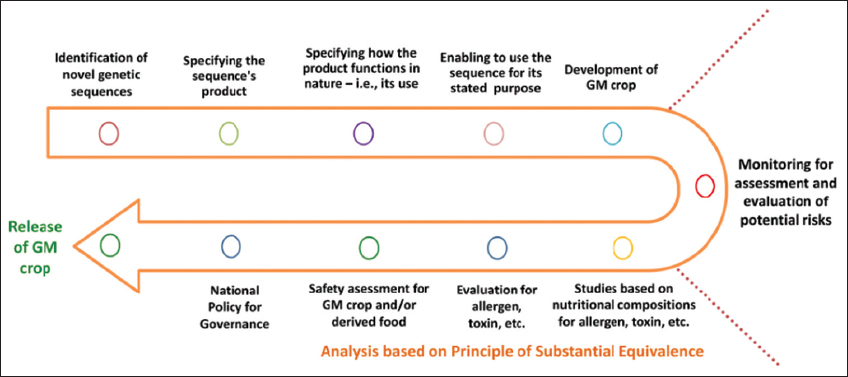

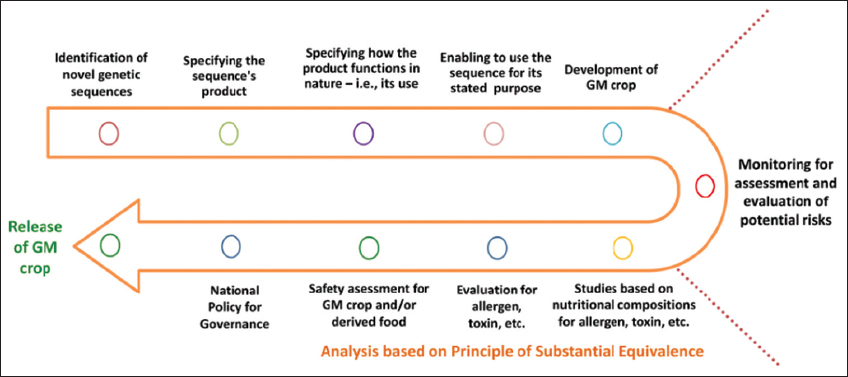

Generally, GM foods are derived from GM crops/plants. GM crop/plant variety is derived from its conventional variety, having manipulated gene(s) that leads to changes in protein(s) and associated metabolite(s) [Figure 5]. The health risks associated with GM crops are basically due to proteins expressed in GM crops from the engineered gene(s) to impart desired trait(s). These expressed proteins could be allergenic or toxic, which may be challenging for the environment along human health. A multi-factorial food safety assessment paradigm has to be utilized for every individual GM crop/food (from its first generation) and its non-GM counterpart, for substantial equivalence. In general, the safety assessment of GM crops and/or derived foods is primarily based on the concept of substantial equivalence or comparative safety assessment (CSA). The CSA is considered the first step for the safety assessment of GM crops and/or derived foods to identify similarities and differences between the foods derived from GM crops and their conventional counterpart (having a long history of safe use). The differences are subjected to further scientific analyses to identify the change in nutrients, toxins, and allergens present in GM crops and/or derived foods through wet lab experiments, bioinformatics tools, in vitro studies, and statistical interpretations. The strategy to access food safety was initially proposed by the WHO [28]. Then, several recommendations were published for food safety and risk associated with GM crops from several organizations like the food and agriculture organization (FAO), the World Health Organization (WHO), the Codex Alimentarius Commission (Codex), the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the International Life Sciences Institute, the International Society for Biosafety Research, the European Commission (EC) and the European Food Safety Authority. The guidelines for legal and regulatory frameworks for food safety have been provided by Codex Alimentarius Commission as “Guidelines for the Conduct of Food Safety Assessment of Foods Derived from Recombinant DNA Plants (CXG 45–2003)” (CAC, 2003; https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/codex-texts/guidelines/en/assessed October on 28, 2021). Due to the complexity of food constituents, food safety has to be considered a multifaceted concept. Food safety must be ensured in the light of science, keeping the risk to an absolute minimum. A science-based evaluation system for screening GM crops and derived food has been supported by FAO. This may include genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics studies.

| Figure 5: The illustration shows the steps involved in the development, assessment, analysis, and approval for the release of GM crops.

[Click here to view] |

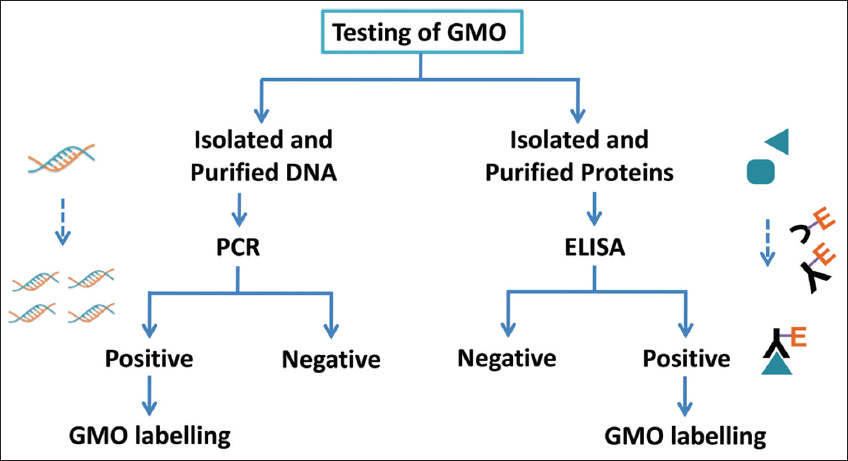

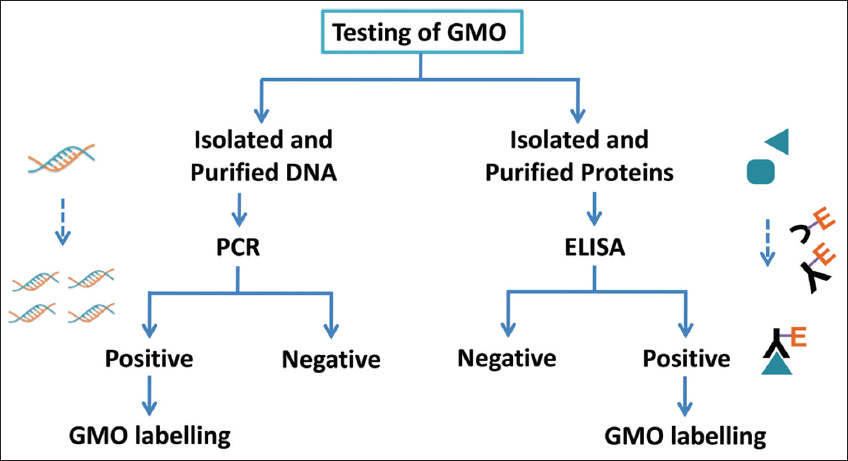

The genomics and transcriptomic studies involve polymerase chain reaction (PCR), sequencing, and microarrays for detecting the differences in the sequence of the gene(s) and expression/suppression of gene(s). PCR is the most commonly used tool for analyzing genetic manipulations [Figure 6]. This involves the isolation of high-quality DNA of sufficient length (ISO/IEC 21571: 2005) to be amplified by PCR. The variants of PCR, such as multiplex PCR, qPCR (or real-time PCR), and microarray, are being employed for the detection of several targets in one experiment. The PCR and its variants are specific in detecting the inserts of DNA fragments (or the GM elements or other changes in the genetic make-up [Table 4].

| Figure 6: Schematic representation for testing of genetically modified organisms.

[Click here to view] |

5. IMPACTS AND IMPLICATIONS

The issues and concerns related to food safety have been around since time immemorial, starting with the trial-and-error method. Historical account for food safety was ensured to reduce food-borne illness and toxicity through different food preparation techniques, such as cooking, salting, canning, and fermentation. Recent trends in biotechnology are based on genetic engineering, which involves the modification of the genome by the transfer of genes (recombinant-DNA; rDNA) among species or by editing the genome, which may not occur naturally. The two important concerns associated with the rDNA plants, referred to as GM crop plants, are (i) the horizontal gene transfer (HGT) and (ii) the impact of a gene expressed. Recent research and literature related to GMO safety are increasing. These days, scientific research and meta-analysis are being conducted by analyzing the peer-reviewed literature on agro-environmental impact, associated risk, and biosafety of GM plants.

The term GMO has controversies as producers’ and consumers’ benefits are accompanied by potential risks and side-effects associated with biomedical and environmental factors. Public concerns are increasing, particularly with GM foods. Complex studies are being conducted across the globe from field to plate to evaluate the potential advantages and disadvantages of such crops and derived foods. The voice raised by various groups of scientists has failed to reach the consumers or the public - creating a negative consensus of GM among the public. The nature of GMOs and the current agricultural problems shall be comprehensively understood before making any consensus. Several intellectuals related to food, nutrition, and food safety collectively are in agreement that GMOs are safe for human consumption [29,30]. Several incidents related to the destruction of hard work resulting by activists are being condemned by the scientific community. For example, the GM wheat and Golden Rice. GM wheat developed by CSIRO, Australia, was destroyed entirely as a protest by a non-governmental environmental organization in July 2011. In August 2013, the field of Golden Rice, managed by IRRI Philippines and other partner organizations, was attacked by activist groups. Notably, the Golden Rice is a result of 25 years of exhaustive work, designed and developed as one of the cheapest and most effective ways of delivering Vitamin A. The rice expresses high levels of β-carotene, a Vitamin A precursor.

5.1. Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT)

DNA is chemically identical regardless of its source and is considered a harmless component of most foods that we eat. Every food that is derived from life forms contains DNA, either intact or in small fragments. Since antiquity, humans have consumed DNA from foods (whole/processed). It is estimated that about 0.1–1.0 g of DNA is being consumed daily by humans [31]. In the case of GM food, the transgenic DNA (rDNA) would be estimated to be <0.0001% of total DNA. There is no confirmation that any bacterial or plant genes are regularly incorporated into the human genome [32].

GM crops have genes conferring antibiotic resistance (AR) as selectable markers. The AR gene encodes for resistance to those antibiotics that are not widely used in medicine because of widespread resistance. Commonly used safe selectable markers are the nptII gene (confer resistance to neomycin and kanamycin) and the aad3 gene (confer resistance to streptomycin and spectinomycin [2]. Such genes are available in the environment naturally, including gut bacteria [33].

The HGT is a frequent event in gut microbiota, facilitated by the process of conjugation and transduction in the lower GI tract [34-36]. The increased use of probiotics and other fermented food preparations has a mass of microbes that may act as donors or recipients of certain AR genes in the human GI tract [37]. Juricova et al. reported that out of 259 isolates of gut microbes, 124 contain at least one gene encoding AR in poultry [38]. Baumgartner et al. found that resident microbes suppress the growth and prevent the evolution of AR of individual species [39]. The possibility of AR gene transfer in bacteria may compromise the effectiveness of antibiotics and adversely impact the anti-microbial therapy. Bacterial gene flow is an established naturally occurring phenomenon [40]. It would be extremely improbable for a plant to transfer genes to a bacterial species because (i) the gene has to be excised precisely and intact from the plant chromosome, (ii) survive intact in the consumer’s gut environment, and (iii) be acquired by the bacterium in intact form through a transformation-competent bacterium [33]. Still, the progressive development in modern biotechnology could replace or remove the utilization of AR genes in the future. Research on the bacterial communities in the rhizosphere provides important information on how GM crops affect the environment. According to this study, growing GM maize has little effect on the rhizosphere bacterial population and has little effect on the environment, especially on soil microorganisms [41].

The fate of recombinant DNA (transgene/cisgene) for HGT has been assessed in vitro in gastric, intestinal, and complete digestive tracts or body fluids in cattle, poultry, and humans. Several studies suggested the risk of HGT is insignificant in the human/animal genome. Nevertheless, the incorporation of such a transgene into the germ cells is even lower, making the inheritance of such a transgene to the following generation insignificant [42-44].

5.2. Health Concerns

The rapid digestion of the transgene or its derived proteins confirmed the absence of the transgene in GM-fed cattle and poultry in most cases. However, small pieces of DNA have been found in a few studies [45]. Agodi et al. reported that short pieces of the transgenes were reported in milk as possible contaminants of fecal/airborne material in feed [46]. DNA of the M13 virus, GFP, and Rubisco genes was discovered in the blood and tissue of ingested animals [47,48]. In studies on cows fed with transgenic crops such as maize and soybeans, the recombinant DNA has only been detected in the ruminal solid phase and duodenal digesta of cattle, but not in ruminal liquid and duodenal phases, milk, blood, muscle, liver, spleen, kidney, and feces [49-52].

Several studies have found contrary to such findings. In any organ or tissue sample taken from GM-fed animals, no traces of recombinant DNA or novel proteins have been discovered [53,54]. In studies on transgenic maize-fed poultry, no recombinant DNA was detected in muscle, liver, spleen, kidney, and eggs [49]. In addition, no significant differences in nutritional value and safety of feed derived from GM plants and their non-GM counterparts [55,56].

The GMO-derived proteins are degraded along with any other proteins in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Most dietary proteins are digested by proteases and pepsin in the GI tract, limit exposure to allergenic reactions. However, some studies have reported that the correlation between protein digestion and loss of allergenicity is limited [57,58]. Hence, comprehensive studies related to allergenicity should be carried out precisely. Food allergies are also associated with common foods such as milk, eggs, nuts, wheat, legumes, fish, crustaceans, and molluscs [59]. The presence of allergens is reported in some GM crops, like 2S albumin isoforms from Brazil nut, which were found in transgenic soybeans [53], Phosphinothricin Acetyltransferase Enzyme (PAT) protein in GM maize, and cod proteins (such as Gadc1) in transgenic potatoes [60]. The reported scientific data by researchers on the consumption of GM crops/food indicate the harmful effects on health, contradicting the studies conducted by the biotechnology-based corporate companies [61]. Abnormal young sperm has been reported in rats and mice fed transgenic potatoes and soya. The transgenic crops (such as Corn and Cotton) grazing livestock were found to have reproductive disorders or even life-threatening [62].

The safety test of GM soybeans claimed “substantially equivalent” to the conventional variety, but significant differences between the two were recorded [63,64]. Several peer-reviewed scientific reports indicate the nutritional equivalence of GMOs and their conventional counterparts. Venneria et al. compared the nutritional content and reported variations in the composition of fatty acid content, phenols, polyphenols, carotenoids, Vitamin C, and mineral composition in GM and conventional samples of wheat, tomato, and corn [65]. The FAO and the WHO reported that GMO foods have no allergenic effects, after being evaluated for allergenicity [66]. A meta-analysis of 21 years of field data supports the cultivation of GE maize [67].

Dunn et al. have reviewed 83 studies on GM crops and associated allergenicity. They reported that no human or animal was evident to show increased allergenicity of GM crops in comparison to their conventional counterparts in 80 reported studies [68]. While rest three studies have shown increased sensitization; according to the IgE-mediated mast cell reactivity. Two studies report an increase in specific IgE, eosinophil, and T-helper cell type 2 cytokines with exposure to GM corn compared with its conventional counterpart, but of no clinical significance. The study has concluded that the use of GM products and the risk of food allergies are not linked. They reported that consumption of GM proteins causes allergy in individuals who are allergic at baseline. Bt toxin Cry1Ac has been reported as a potent antigen delivered oral/nasal [69]. Even some farmworkers have IgE-mediated skin sensitization when exposed to Bacillus thuringiensis-based pesticides [70]. Aris and Leblanc claim the presence of Bt toxin in maternal blood [71]. Notably, the toxin is inactive in an acidic environment (as in the stomach of humans), and active in an alkaline environment (as in an insect’s gut). There is no Bt toxin receptor in humans. Nelson suggests that the crystal-like proteins produced by the B. thuringiensis have no effects on mammals [72].

5.3. Socio-economic Concerns

There is a lot of disagreement around GM crops, which is being echoed continuously. Even, consumers have a strong perception that foods with a long history of safe use are safe for consumption. Controversies are associated with GM crops, involving farmers, consumers, government, NGOs, and environmentalists. Consumers’ concerns for the quality of food were known before the advent of food derived from GM crops. GM crops may have an impact on the health of consumers that might be risky. Consumer acceptance is associated with socio-economic determinants [73], such as price premiums, option values, willingness to pay, age, gender, and educational level.

Usually, consumers consider conventional foods safe for consumption. Conventional foods have an established record of consumption for decades/centuries. The genetic manipulations and altered expression may have beneficial or detrimental effects in comparison to conventional. Therefore, evaluation and risk assessment of GMOs and GM foods should be conducted as per the Codex guidelines for allergenicity, toxicity, loss of biodiversity, gene transfer, and outcrossing (migration of genes from GM to feral and wild relatives).

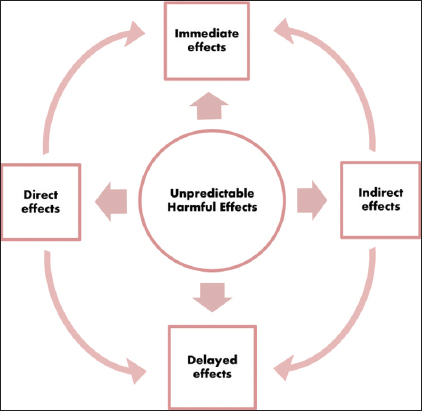

The major traits gained with genetic modifications are disease and pest resistance. This makes farmers happy to cultivate their crops for more economic gain with minimal yield loss. However, the widespread release and cultivation of such GM crops at a commercial scale may pose a strong selection-for-survival pressure. This selective pressure is strong enough to be the reason behind the evolution of resistant pests, like superbugs. This may cause the failure of such GM crops in a few years, leading to controversy over the use of biotechnology, such as the Monarch Butterfly Controversy (1999) and the Seralini Affair (2012). The controversies related to safety concerns are being raised for GM crops/food on several levels by consumers, farmers, policymakers, regulatory bodies, and the government. The concern for the modern biotechnology needed for sustainable agriculture to address the scarcity of food, feed, and fodder; is safe for the health and the environment? is required to be addressed.

Developing countries like India have small and marginal farmers. Farmers cite that the high cost of weeding considerably goes down by growing HtBt cotton and using glyphosate against weeds. As claimed, cultivation of Bt Brinjal reduces the total production cost by reducing the use of pesticides. Large-scale sowing of unapproved GM crops such as HTBt cotton and Bt Brinjal, is being reported in several states of India, such as Maharashtra and Haryana. A few farmers are arrested and charged for sowing unapproved GM variants with a jail term of 5 years and a fine of Rs 1 Lakh under the Environmental Protection Act, 1989 [74]. The right to environmental information was recently emphasized by the Indian Supreme Court in a divided decision over the release of GM mustard. One of the two judges on the court argued against the crop’s release, pointing to a lack of adequate evaluation of its health effects, while the other referred to the conditional clearance as progressive. It is suggested that consumers’ knowledge be used as a control variable in future studies [75]. In July 2024, the court ordered the government to engage with every relevant stakeholder, including states, independent experts, and farmers’ organizations, to draft a national policy on GMOs. The action highlights how important it is for policy to be informed by both scientific data and societal demands and expectations. It demonstrates the importance of broader public involvement in synthetic biology (SynBio) interventions [76]. Small farmers’ willingness to engage in collaborative GM crop farming is favorably influenced by their expectations of GM technology’s profitability as well as their sense of their market adaptability [77].

The seeds are expensive in comparison to local non-GM varieties; farmers must purchase new seeds every sowing season as seeds cannot be reused. BT cotton is resistant to a specific type of cotton pest, not all pests of cotton. However, regular and prolonged spraying of herbicides/insecticides may cause the evolution of tolerant/resistant weeds/insects due to strong selective pressure in a given habitat [78,79]. Pests are developing resistance against Bt Cotton, making the GM-based strategy for pest control unsustainable [80]. To prevent this, certain crop management strategies that limit the growth of pest populations that have surmounted crop resistance mechanisms might be used. The use of GM crops with a high level of Bt gene expression and the simultaneous deployment of a refuge made up of non-GM, pest-susceptible crops constitute the most widely used resistance management technique for Bt crops, known as the high dose/refuge strategy. This strategy is based on the assumption that insects that are resistant to Bt endotoxins evolve as a result of recessive mutations that have only a low allele frequency in the population of insects. Only the extremely uncommon insects homozygous for the mutant allele will survive on the GM crops due to the high amount of Bt endotoxin expression in those crops. By planting refuge non-GM crops near the GM crop region, it should be ensured that the rare mutant homozygous resistant insects living in the GM crop area mate with non-mutant, susceptible insects from the refuge. As a result, their offspring will carry the mutant allele heterozygously and be prone to the GM crop.

It is suggested that refuges comprise 20–50% of the area that is planted with the GM crop, depending on the crop and the conditions of the area. Mathematical simulations and actual experience suggest that implementing this strategy as part of an integrated framework of pest management could prevent the emergence of resistant pests for decades [81,82]. However, the deployment of refuges may not be financially feasible or may be disregarded owing to ignorance, particularly in the case of small-scale, resource-poor farmers in developing nations [16]. Therefore, it is suggested that analyses of the emergence of resistant insect populations and compliance with refuge suggestions be incorporated into post-release monitoring programs. This might ensure that refuge suggestions are followed and that the value of GM crops that express pest resistance characteristics is maintained.

5.4. Consumer Concerns

The public debate, attitude, and expression for acceptance or rejection make several non-governmental organizations work on issues related to GMOs with explicit interests. Most research assesses people’s attitudes toward GM food consumption by conducting a surveys, opinion polls, or product feedback on national and international levels [83]. The most prominent ethical concern raised with GMOs is that “tampering with nature may lead to unintended and unpredictable effects” [84].

An interesting case of GMO corn, StarLink (approved for animal feeding), that happened in 2000, was popularized when the corn was recalled. The StarLink corn has the gene for a Bt toxin (Cry9C), which selectively kills destructive insect larvae. The USFDA did not find any association between Cry9C and allergic reactions [85].

A study conducted in Spain concluded that the consumers demanded GM foods accompanied by strict policies; to confirm the safety of consumers, decreasing the consumer-perceived risk dealing with health-related concerns [86]. In 2011, studies related to the variables influencing consumers’ decisions to choose GM-free foods were conducted in the European cities of Drama, Kavala, and Xanthi as field interviews of 337 consumers. The principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted in order to identify the factors that influence customers. To prefer GM-free products are (i) product labeling and certification – as GM-free or organic, (ii) label to claim environmental protection, a label of nutritional value, marketing issues, price, and quality. The consumers are further categorized into two: (i) influenced by elements including product cost, quality, and marketing and (ii) interested in environmental preservation and product certification [87].

Snell et al. conducted long-term and multigenerational studies on the effects of GM feed containing GM varieties of maize, potato, soybean, rice, or triticale on animal health. This involves 12 long-term studies for a duration of 90 days to 2 years, and 12 multigenerational studies involving 2–5 generations. They examined the parameters such as biochemical, histological, hematology, and transgenic DNA detection. They found small differences that are not statistically significant and hence have no biological or toxicological importance. The study can be concluded as GM plants could be utilized as safe food and feed because they have the same nutritional value as their non-GM counterparts [88].

REFERENCES

1. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). High Level Expert Forum-How to Feed the World in 2050. Rome:Food and Agriculture Organization.

2. Saurabh S, Vidyarthi AS, Prasad D. RNA interference:Concept to reality in crop improvement. Planta. 2014;239:543-64.[CrossRef]

3. Carpenter J, Felsot A, Goode T, Hammig M, Onstad D, Sankula S. Comparative environmental impacts of biotechnology-derived and traditional soybean, corn, and cotton crops. Council for Agricultural Science and Technology, Ames, Iowa. www.cast-science.org. Sponsored by the United Soybean Board. Available from: www.unitedsoybean.org. 2002. [Last accessed on 2024 Dec 07].

4. Lemaux PG. Genetically engineered plants and foods:A scientist's analysis of the issues (part I). Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:771-812.[CrossRef]

5. Del-Aguila-Arcentales S, Alvarez-Risco A, Rojas-Osorio M, Meza-Perez H, Simbaqueba-Uribe J, Talavera-Aguirre R, et al. Analysis of genetically modified foods and consumer:25 years of research indexed in scopus. J Agric Food Res. 2025;19:101594.[CrossRef]

6. James C. Brief 49 Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops:2014. Ithaca, NY:ISAAA Briefs;2014.

7. Saurabh S. Genome editing:Revolutionizing the crop improvement. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2021;39(4):752-72.[CrossRef]

8. Steinwand MA, Ronald PC. Crop biotechnology and the future of food. Nat Food. 2020;1(5):273-83.[CrossRef]

9. Butler D, Reichhardt T. Assessing the threat to biodiversity on the farm. Nature. 1999;398:654-6.[CrossRef]

10. Jank B. Gaugitsch H. Decision making under the Cartagena protocol on biosafety. Trends Biotechnol. 2001;19(5):194-7.[CrossRef]

11. Kinderlerer J. The Cartagena protocol on biosafety. Collect Biosaf Rev. 2008;4(S 12):16-65.

12. Bartsch D. 3. Issues and challenges in monitoring GM crop-specific traits. Genetically modified organisms In:Crop Production and their Effects on the Environment:Methodologies for Monitoring and the Way Ahead. Rome:Food and Agriculture Organization;2006. 60.

13. Wilhelm R, Beißner L, Schiemann J. Concept for the realisation of a GMO-monitoring in Germany. Nachrichtenblatt Deutsch Pflanzenschutzdienstes. 2003;55:258-72.

14. Züghart W, Benzler A, Berhorn F, Sukopp U, Graef F. Determining indicators, methods and sites for monitoring potential adverse effects of genetically modified plants to the environment:The legal and conceptional framework for implementation. Euphytica. 2008;164:845-52.[CrossRef]

15. Sonnino A, Dhlamini Z, Santucci FM, Warren P. Socio-Economic Impacts of Non-Transgenic Biotechnologies in Developing Countries:The Case of Plant Micropropagation in Africa. Rome:Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO);2009.

16. Suman Sahai SS. Assessing the Socio-Economic Impact of GE Crops. Rome:FAO;2006. 121-3.

17. FAO. Genetically Modified Organisms in Crop Production and their Effects on the Environment:Methodologies for Monitoring and the Way Ahead. Rome;2005. Available from: https://www.fao.org/docrep/009/a0802e/a0802e00.htm [Last accessed on 2024 Dec 07].

18. Ghosh A. The limits of biotechnology:India's GMO policy and global impact. Biotechnol Adv. 2021;39:107-15.

19. Nandi I, Ranjan D. The GMO approval process in India:Challenges and hope. India J Agric Econ. 2018;73(1):20-35.[CrossRef]

20. Bhan N. Consumer preferences and GMO opposition in India. J Food Policy. 2016;61:50-60.

21. Kumar S. Political dimensions of agricultural biotechnology in India. Agric Econ. 2020;51(2):231-40.

22. Sharma R. GMO and small farmers:A critical analysis. Int J Agric Food Sci. 2019;9(1):44-56.

23. Kumar V, Turner S. The role of biodiversity in India's agricultural policies. Environ Sci Policy. 2021;115:23-31.[CrossRef]

24. Sahu P, Verma R. Unapproved GM crop adoption in India:Economic implications for farmers. Agric Econom Rev. 2023;45(2):203-18.

25. Singh A, Gupta M, Sharma K. The unregulated rise of GM crops in Indian fields:An ethnographic study. Field Stud Agric. 2023;11(4):78-90.

26. Basu S. The future of GM crops in India:A regulatory perspective. J Agric Biotechnol. 2022;4(1):12-25.

27. Kumar R, Rai P. Navigating agricultural biotechnologies in India:Policies and practices. Indian J Agric Sci. 2022;92(3):341-52.

28. WHO. Strategies for Assessing the Safety of Foods Produced by Biotechnology:Report of a Joint FAO. Geneva, Switzerland:World Health Organization;1991.

29. Tijerino MB, Darbishire LC, Chung MM, Esler GC, Liu AC, Savaiano DA. Genetically modified organisms can be organic. Nutr Today. 2021;56:26-32.[CrossRef]

30. Hefferon KL, Miller HI. Flawed scientific studies block progress and sow confusion. GM Crops Food. 2020;11(3):125-9.[CrossRef]

31. Flachowsky G, Aulrich K, Böhme H, Halle I. Studies on feeds from genetically modified plants (GMP)-contributions to nutritional and safety assessment. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2007;133(1-2):2-30.[CrossRef]

32. Goldstein DA, Tinland B, Gilbertson LA, Staub JM, Bannon GA, Goodman RE, et al. Human safety and genetically modified plants:A review of antibiotic resistance markers and future transformation selection technologies. J Appl Microbiol. 2005;99(1):7-23.[CrossRef]

33. Jonas DA, Elmadfa I, Engel KH, Heller KJ, Kozianowski G, König A, et al. Safety considerations of DNA in food. Ann Nutr Metab. 2001;45(6):235-54.[CrossRef]

34. McInnes RS, McCallum GE, Lamberte LE, Van Schaik W. Horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in the human gut microbiome. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2020;53:35-43.[CrossRef]

35. Van Schaik W. The human gut resistome. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015;370:20140087.[CrossRef]

36. Huddleston JR. Horizontal gene transfer in the human gastrointestinal tract:Potential spread of antibiotic resistance genes. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;7:167-76.[CrossRef]

37. Schjørring S, Krogfelt KA. Assessment of bacterial antibiotic resistance transfer in the gut. Int J Microbiol. 2011;2011:312956.[CrossRef]

38. Juricova H, Matiasovicova J, Kubasova T, Cejkova D, Rychlik I. The distribution of antibiotic resistance genes in chicken gut microbiota commensals. Sci Rep. 2021;11:3290.[CrossRef]

39. Baumgartner M, Bayer F, Pfrunder-Cardozo KR, Buckling A, Hall AR. Resident microbial communities inhibit growth and antibiotic-resistance evolution of Escherichia coli in human gut microbiome samples. PLoS Biol. 2020;18(4):3000465.[CrossRef]

40. Aminov RI. Horizontal gene exchange in environmental microbiota. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:158.[CrossRef]

41. Jang YJ, Oh SD, Hong JK, Park JC, Lee SK, Chang A, et al. Impact of genetically modified herbicide-resistant maize on rhizosphere bacterial communities. GM Crops and Food. 2025;16(1):186-98.[CrossRef]

42. Giraldo PA, Cogan NO, Spangenberg GC, Smith KF, Shinozuka H. Development and application of droplet digital PCR tools for the detection of transgenes in pastures and pasture-based products. Front Plant Sci. 2019;9:408128.[CrossRef]

43. Netherwood T, Martín-Orúe SM, O'Donnell AG, Gockling S, Graham J, Mathers JC, et al. Assessing the survival of transgenic plant DNA in the human gastrointestinal tract. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22(2):204-9.[CrossRef]

44. Abbas MS. Genetically engineered (modified) crops (Bacillus thuringiensis crops) and the world controversy on their safety. Egypt J Biol Pest Control. 2018;28(1):1-2.[CrossRef]

45. Nadal A, De Giacomo M, Einspanier R, Kleter G, Kok E, McFarland S, et al. Exposure of livestock to GM feeds:Detectability and measurement. Food Chem Toxicol. 2018;117:13-35.[CrossRef]

46. Agodi A, Barchitta M, Grillo A, Sciacca S. Detection of genetically modified DNA sequences in milk from the Italian market. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2006;209(1):81-8.[CrossRef]

47. Guertler P, Paul V, Albrecht C, Meyer HH. Sensitive and highly specific quantitative real-time PCR and ELISA for recording a potential transfer of novel DNA and Cry1Ab protein from feed into bovine milk. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2009;393:1629-38.[CrossRef]

48. Brigulla M, Wackernagel W. Molecular aspects of gene transfer and foreign DNA acquisition in prokaryotes with regard to safety issues. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;86:1027-41.[CrossRef]

49. Einspanier R, Klotz A, Kraft J, Aulrich K, Poser R, Schwägele F, et al. The fate of forage plant DNA in farm animals:A collaborative case-study investigating cattle and chicken fed recombinant plant material. Eur Food Res Technol. 2001;212:129-34.[CrossRef]

50. Phipps RH, Beever DE, Humphries DJ. Detection of transgenic DNA in milk from cows receiving herbicide tolerant (CP4EPSPS) soyabean meal. Livest Prod Sci. 2002;74(3):269-73.[CrossRef]

51. Phipps RH, Deaville ER, Maddison BC. Detection of transgenic and endogenous plant DNA in rumen fluid, duodenal digesta, milk, blood, and feces of lactating dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2003;86(12):4070-8.[CrossRef]

52. De Giacomo M, Di Domenicantonio C, De Santis B, Debegnach F, Onori R, Brera C. Carry-over of DNA from genetically modified soyabean and maize to cow's milk. J Anim Feed Sci. 2016;25(2):109-15.[CrossRef]

53. Nordlee JA, Taylor SL, Townsend JA, Thomas LA, Bush RK. Identification of a Brazil-nut allergen in transgenic soybeans. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(11):688-92.[CrossRef]

54. Streit LG, Beach LR, Register JC, Jung R, Fehr WR. Association of the Brazil nut protein gene and Kunitz trypsin inhibitor alleles with soybean protease inhibitor activity and agronomic traits. Crop Sci. 2001;41(6):1757-60. [CrossRef]

55. Flachowsky G, Chesson A, Aulrich K. Animal nutrition with feeds from genetically modified plants. Arch Anim Nutr. 2005;59(1):1-40.[CrossRef]

56. Beagle JM, Apgar GA, Jones KL, Griswold KE, Radcliffe JS, Qiu X, et al. The digestive fate of Escherichia coli glutamate dehydrogenase deoxyribonucleic acid from transgenic corn in diets fed to weanling pigs. J Anim Sci. 2006;84(3):597-607.[CrossRef]

57. Fu TJ, Abbott UR, Hatzos C. Digestibility of food allergens and nonallergenic proteins in simulated gastric fluid and simulated intestinal fluid-a comparative study. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50(24):7154-60.[CrossRef]

58. Herman R, Gao Y, Storer N. Acid-induced unfolding kinetics in simulated gastric digestion of proteins. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2006;46(1):93-9.[CrossRef]

59. Maryanski JH. Bioengineered Foods:Will they Cause Allergic Reactions. New York:US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Centre for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN);1997.

60. Bindslev-Jensen C, Poulsen LK. Hazards of unintentional/intentional introduction of allergens into foods. Allergy. 1997;52(12):1184-6.[CrossRef]

61. Munro S. GM food debate. Lancet. 1999;354(9191):1727-9.[CrossRef]

62. Maghari BM, Ardekani AM. Genetically modified foods and social concerns. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2011;3(3):109-17.

63. Padgette SR, Taylor NB, Nida DL, Bailey MR, MacDonald J, Holden LR, et al. The composition of glyphosate-tolerant soybean seeds is equivalent to that of conventional soybeans. J Nutr. 1996;126(3):702-16.[CrossRef]

64. Taylor NB, Fuchs RL, MacDonald J, Shariff AR, Padgette SR. Compositional analysis of glyphosate-tolerant soybeans treated with glyphosate. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47(10):4469-73.[CrossRef]

65. Venneria E, Fanasca S, Monastra G, Finotti E, Ambra R, Azzini E, et al. Assessment of the nutritional values of genetically modified wheat, corn, and tomato crops. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56(19):9206-14.[CrossRef]

66. WHO. Frequently Asked Questions on Genetically Modified Foods. Geneva:World Health Organization;2014. Available from: https://www.who.int/foodsafety/areas_work/food/technology/frequently_asked_questions_on_gm_foods.pdf?ua=1[Last accessed on 2021 Dec 03].

67. Pellegrino E, Bedini S, Nuti M, Ercoli L. Impact of genetically engineered maize on agronomic, environmental and toxicological traits:A meta-analysis of 21 years of field data. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):3113.[CrossRef]

68. Dunn SE, Vicini JL, Glenn KC, Fleischer DM, Greenhawt MJ. The allergenicity of genetically modified foods from genetically engineered crops:A narrative and systematic review. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119(3):214-22.3.[CrossRef]

69. Vázquez-Padrón RI, Gonzáles-Cabrera J, García-Tovar C, Neri-Bazan L, Lopéz-Revilla R, Hernández M, et al. Cry1Ac protoxin from Bacillus thuringiensis sp. HD73 binds to surface proteins in the mouse small intestine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;271(1):54-8.[CrossRef]

70. Bernstein IL, Bernstein JA, Miller M, Tierzieva S, Bernstein DI, Lummus Z, et al. Immune responses in farm workers after exposure to Bacillus thuringiensis pesticides. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107(7):575-82. [CrossRef]

71. Aris A, Leblanc S. Maternal and fetal exposure to pesticides associated to genetically modified foods in eastern townships of Quebec, Canada. Reprod Toxicol. 2011;31(4):528-33.[CrossRef]

72. Nelson GC. Genetically Modified Organisms in Agriculture:Economics and Politics. Netherlands:Elsevier;2001.

73. Garcia-Yi J, Lapikanonth T, Vionita H, Vu H, Yang S, Zhong Y, et al. What are the socio-economic impacts of genetically modified crops worldwide?A systematic map protocol. Environ Evid. 2014;3:24.[CrossRef]

74. Jebaraj P. Available from: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/sale-of-illegal-htbt-cotton-seeds-doubles/articl34852355.ecen [Last accessed on 2021 Oct 29].

75. Hui X, Amponsah RK, Antwi S, Gbolonyo PK, Ameyaw MA, Bentum-Micah G, et al. Understanding the societal dilemma of genetically modified food consumption:A stimulus-organism-response investigation. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2024;8:1364052.[CrossRef]

76. Todi S, Dixson H. People must be at the heart of GMO policies:Concerns over safety of genetically modified products will persist unless the public is engaged with the science behind them. Nat India. 2024.

77. Pang Y, Zou H, Jia C, Gu C. Expected profitability, independence, and risk assessment of small farmers in the wave of GM crop collectivization--evidence from Xinjiang and Guangdong. GM Crops and Food. 2025;16(1):97-117.[CrossRef]

78. Louda SM. Insect limitation of weedy plants and its ecological implications. In:Traynor PL, Westwood JH, editors. Proceedings of a Workshop on:Ecological Effects of Pest Resistance Genes in Managed Ecosystems. Information Systems for Biotechnology. Faculty Publications in the Biological Sciences;1999. 43-8. Available from: https://www.isb.vt.edu [Last accessed on 2024 Dec 07].

79. Steinbrecher RA. From green to gene revolu [Last accessed on 2024 Dec 07]. :The environmentally risks of genetically engineered crops. Ecologist. 1996;26(6):273-82.

80. Zhang H, Yin W, Zhao J, Jin L, Yang Y, Wu S, et al. Early warning of cotton bollworm resistance associated with intensive planting of Bt cotton in China. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):22874.[CrossRef]

81. Conner AJ, Glare TR, Nap JP. The release of genetically modified crops into the environment. Part II. Overview of ecological risk assessment. Plant J. 2003;33(1):19-46.[CrossRef]

82. EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). Introduction to Biotechnology Regulation for Pesticides;2008. Available from: https://epa.gov/pesticides/biopesticides/regtools/biotech/reg/prod.htm [Last accessed on 2024 Dec 07].

83. Hamstra A. Public Opinion About Biotechnology. A Survey of Surveys. The Hague:European Federation of Biotechnology;1998.

84. Miles S, Frewer LJ. Investigating specific concerns about different food hazards. Food Q Prefer. 2001;12(1):47-61.[CrossRef]

85. Bucchini L, Goldman LR. Starlink corn:A risk analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(1):5-13.[CrossRef]

86. Martinez-Poveda A, Molla-Bauza MB, Del Campo Gomis FJ, Martinez LM. Consumer-perceived risk model for the introduction of genetically modified food in Spain. Food Policy. 2009;34(6):519-28.[CrossRef]

87. Tsourgiannis L, Karasavvoglou A, Florou G. Consumers'attitudes towards GM free products in a European region. The case of the prefecture of drama-kavala-xanthi in greece. Appetite. 2011;57(2):448-58.[CrossRef]

88. Snell C, Bernheim A, BergéJB, Kuntz M, Pascal G, Paris A, et al. Assessment of the health impact of GM plant diets in long-term and multigenerational animal feeding trials:A literature review. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;50(3-4):1134-48.[CrossRef]

89. Rischer H, Oksman-Caldentey KM. Unintended effects in genetically modified crops:Revealed by metabolomics?Trends Biotechnol. 2006;24(3):102-4.[CrossRef]

90. Goodman RE. Twenty-eight years of GM food and feed without harm:Why not accept them?GM Crops and Food. 2024;15(1):40-50.[CrossRef]

91. Wu W, Zhang A, Van Klinken RD, Schrobback P, Muller JM. Consumer trust in food and the food system:A critical review. Foods. 2021;10(10):2490.[CrossRef]

92. Sutherland C, Gleim S, Smyth SJ. Correlating genetically modified crops, glyphosate use and increased carbon sequestration. Sustainability. 2021;13(21):11679.[CrossRef]

93. Sathee L, Jagadhesan B, Pandesha PH, Barman D, Adavi BS, Nagar S, et al. Genome editing targets for improving nutrient use efficiency and nutrient stress adaptation. Front Genet. 2022;13:900897.[CrossRef]

94. G?owacka K, Kromdijk J, Kucera K, Xie J, Cavanagh AP, Leonelli L, et al. Photosystem II subunit S overexpression increases the efficiency of water use in a field-grown crop. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):868.[CrossRef]

95. Brookes G, Smyth SJ. Risk-appropriate regulations for gene-editing technologies. GM Crops Food. 2024;15(1):1-14.[CrossRef]

96. Smith J, Brown L, Taylor R. Consumer trust and transparency in GM food labeling:A critical analysis. J Agric Econom. 2024;32(1):45-67.

97. Jones M, Wilson T. Eco-conscious consumerism:Trends and implications for GM crop marketing. Food Q Prefer. 2025;78:203-15.

98. Lee A, Roberts D, Singh P. The role of technology in environmental monitoring of GM crops. Environ Sci Technol. 2023;57(6):1203-10.

99. Patel S, Zheng Y. GM crops and sustainable agriculture:Assessing the carbon footprint. Sustainability. 2025;15(3):671-89.

100. Nguyen H, Thompson R, Chang E. Evaluating ecological impacts of GM agriculture:Methods and results. Ecol Application. 2024;34(2):12345.

101. Garcia J, Kim T. Stakeholder collaboration for sustainable GM crop production:Opportunities and challenges. Agric Hum Values. 2025;42(4):671-84.

102. Brookes G. Genetically modified (GM) crop use 1996-2020:Environmental impacts associated with pesticide use change. GM Crops Food. 2022;13(1):262-89.[CrossRef]

103. Ngongolo K, Mmbando GS. Necessities, environmental impact, and ecological sustainability of genetically modified (GM) crops. DiscovAgric. 2025;3:29.[CrossRef]

104. Klümper W, Qaim M. A meta-analysis of the impacts of genetically modified crops. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):111629.[CrossRef]

105. Benbrook C. Who Benefits from GMOs?A Comparative Analysis of Effects from GM Crops. Geneva:Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy;2012.

106. EC (European Commission). EU Legislation on Genetically Modified Organisms. European:European Commission;2021.

107. ISAAA (International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications). Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops in 2020. India:ISAAA;2021.

108. Aerni P. Global trade and biotechnology:The impact of GMOs and the role of the WTO. Food Policy. 2007;32(1):53-68.

109. Gaskell G, Allansdottir A, Allum N, Corchero C, Fischler C, Hampel J, et al. Europeans and biotechnology in 2005:patterns and trends. Final report on Eurobarometer. 2006;64(3):1-85.

110. Funk C, Tyson A, Kennedy B, Johnson C. Science and scientists held in high esteem across global publics. Pew Res Center. 2020;29:1-133.