1. INTRODUCTION

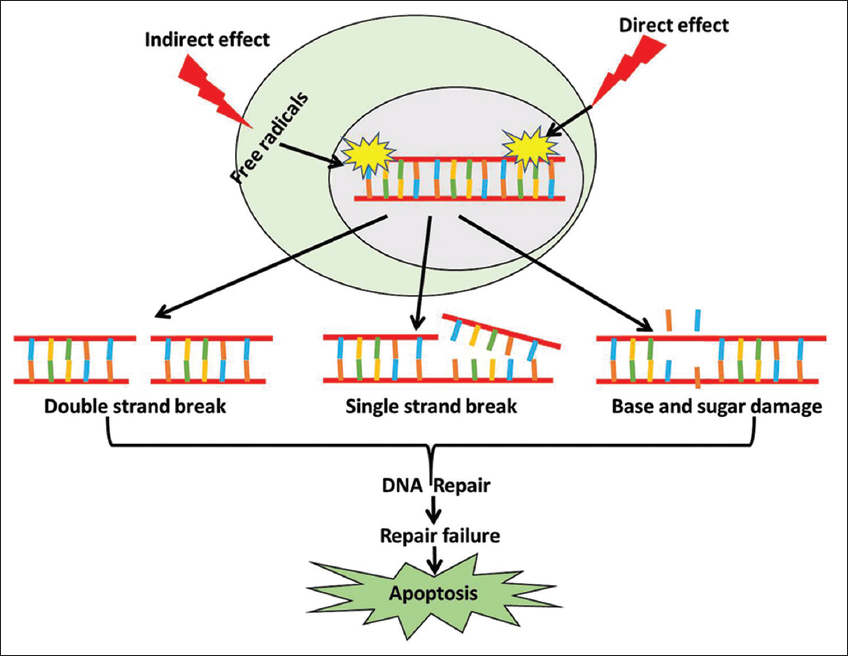

Radiation therapy is one of the widely accepted therapies for the majority of cancers that uses beams of intense energy to kill cancer cells and shrink the tumor. High-energy radiation damages the genetic material of cells and inhibits their further proliferation and division [1]. Ionizing radiation can cause deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) damage directly or indirectly by producing free radicals [Figure 1]. Ionizing radiation generates free radicals and reactive oxygen species leading to DNA damage followed by apoptosis [2]. DNA damages caused by the ionizing radiation activate DNA damage repair systems and failure, which leads to apoptosis [Figure 1]. Ionizing radiation damages the cancer cells and severely affects normal cells. Hence, the purpose of radiation therapy is to enhance the efficacious use of radiation against abnormal cancer cells with low doses of radiation so that the surrounding normal cells are least affected [3]. Apart from radiation therapy, many imaging modalities used for various disease diagnosis include ionizing radiation to generate images that cause damage to the normal cells [4]. Thus, potent radioprotectors for normal cells or radiosensitizers for cancer cells have gained much attention to address radiation-induced challenges depending on the need. The screening procedure of potent radioprotector/radiosensitizer molecules demands a perfect model that may be a cell-based model or an animal model.

| Figure 1: Mechanism of ionizing radiation (IR) induced cell death. IR causes deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) damage directly or indirectly through generation of reactive free radicals. Failure in DNA repair mechanisms induces cell death. [Click here to view] |

The demand for animal models has sharply increased to screen potential radioprotectors and radiosensitizers to elucidate the effect of these molecules in different physiological and genetic setups. The search to explore suitable in-vitro and in-vivo models is to be used to screen radiation modifiers and understand the effect of radiation and modifiers in different physiological conditions with different genetic setups. Here, we summarized many of the major other model systems used to assess radioprotectors and radiosensitizers central to radiation therapy or radiation exposure.

2. IN VITRO MODELS

2.1. Organoid/3D Culture Model

Organoids are three-dimensional tissue-resembling structures that provide better in vivo tumor architecture and are a convenient model for observing cell-cell interaction in comparison to 2D culture systems [5]. Patient-derived organoids (PDOs) are suitable models for rapid testing of multiple drugs and radiation than the time-consuming process of respective patient-derived xenograft (PDX) generation [6]. Hubert et al. demonstrated the potential of glioblastoma organoids to be used as a screening tool to identify radiosensitizers and they found the heterogeneous response of organoids toward radiation [7]. Linkous et al. demonstrated that organoids combining healthy cerebral tissue and glioblastoma cells called GLICO (cerebral organoid glioma) show radioresistance compared to 2D culture [8]. Park et al. suggested valproic acid acted as both radiosensitizer and radioprotector using different species and organ-specific organoid culture as valproic acid protected both mouse and human intestinal organoids whereas sensitized human colorectal cancer organoids toward radiation [9].

Just like other models, organoid models also have some shortcomings. Experiments involving organoids to model tumor xenografts need a repeated collection of tumor tissues or require a replenishable source of tissues for experimental replicates or large-scale culture in the form of organoids. However, this problem can be addressed with PDOs, which are derived from PDXs generated in animal models thus, repeated patient biopsy and tumor tissue collection will not be required [10].

2.2. Cell-based High-throughput Screening

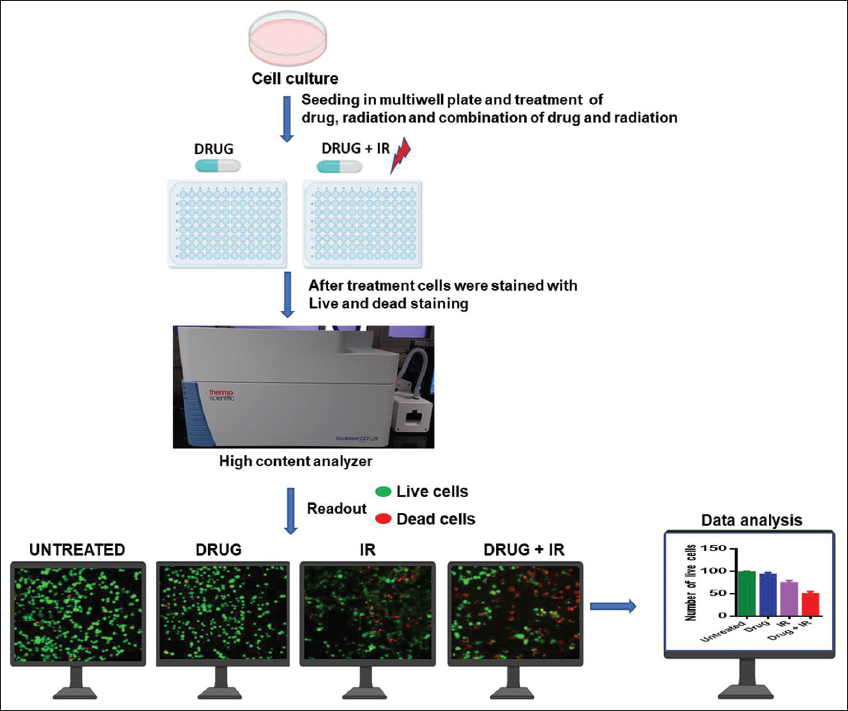

Cell-based assays that represent the multiplication capacity of tumor cells (i.e., clonogenic and survival) and their DNA damage repair activity have been extensively used to characterize the effects of radiosensitizing drugs. Although standard cell culture (2D) condition fails to recapitulate tumor architecture or microenvironmental gradients, it is beneficial for high-throughput screening of multiple drugs within a short period. Targeting a specific pathway or specific molecule is the key to screening the radiosensitizer and radioprotector by cell-based high-throughput screening. Among the targeted pathways are DNA damage and repair pathway [11,12], PI3K-AKT Pathway [13,14], Mevalonate pathway [15-17], Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) Pathway [18,19], and NFΚB Pathway [20-22] are the most highlighted pathways to screen radiosensitizer or radioprotector by cell-based screening. High-throughput screening of radiosensitizer and radioprotector can also be done through live dead staining, as described in Figure 2. One previous study reported a nanoparticle composed of metallic elements Au and Pt (Au-pt-NPS) as a radiosensitizer in murine breast cancer cells line 4T using live dead staining [23].

| Figure 2: High-throughput screening of radiosensitizer using live/dead staining. The cultured cells are transferred to a multiwell plate. Then the cells are treated with drug alone, radiation alone, and both drug and radiation. One condition remains as the untreated condition. After a certain time point, the cells are stained with live/dead staining and analyzed using a high content analyser. [Click here to view] |

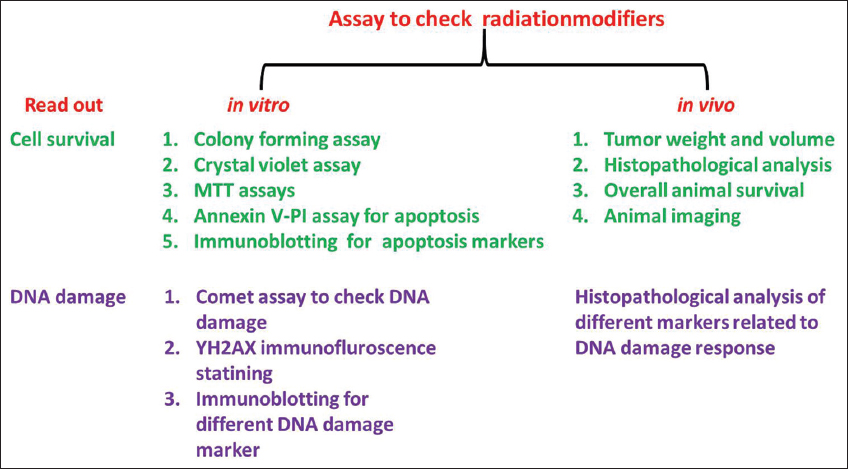

The most affordable, routinely used and generally accepted in-vitro model is the 2D monolayer cell culture because the culture and experiment design is cost-effective, and the cellular behavior on flat and inflexible surfaces can be easily observed. However, a cell culture system in a 2-D fashion holds certain limitations, majorly a structural 3D organization enabling extracellular matrix adhesion is lacking. Cell-cell communication and growth factor signaling are altered and can differ from normal processes. Because of these restrictions, cells growing in a 2D monolayer exhibit unnatural growth kinetics and sometimes aberrant functions and behavior. Different assays are performed to screen the radiosensitizers and radioprotectors in cell culture [Figure 3].

| Figure 3: Different assays to screen radiosensitizer and radioprotector. Various in vitro and in vivo assays could be adapted to evaluate the effects of potential radiation-modifiers. [Click here to view] |

In a study by Ravi et al., small molecule drugs including RAD001, MK2206, BEZ235, MLN0128, and MEK162 were screened using U87 glioblastoma spheroid and noticed that MEK162, the MAPK-targeting agent enhanced the radiosensitivity of glioblastoma spheroids. MEK162 downregulated and dephosphorylated the cell-cycle checkpoint proteins CDK1/CDK2/WEE1 and DNA damage response proteins p-ATM/p-CHK2, suggesting the persistence of prolonged DNA damage [24].

3. IN VIVO MODELS

3.1. Yeast Model System

The fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe and the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae have been valuable models for studying the cellular response toward different antitumor drugs or radiation [25,26]. Interestingly, the previous findings have reported yeast as a perfect model to screen radiosensitizer or radioprotector candidates for clinical use [27,28]. One of the yeast model findings suggests that histone acetyltransferasecan (HAT) be a therapeutic target for radiosensitization by targeting HAT with inhibitors that sensitize wild-type yeast to radiation [29]. In another study, the budding yeast S. cerevisiae was used to evaluate the radiosensitizing efficacy of AK 2123 (sanazole). The result suggested that the treatment of sanazole sensitized yeast cells toward radiation by increasing DNA damage [30]. In a similar study using S. cerevisiae, cisplatin was reported as a radiosensitizer by inhibiting DNA damage repair caused by radiation [31]. Nemavarkar et al. used the budding yeast S. cerevisiae, and antioxidants such as disulfiram, glutathione, curcumin, quercetin, rutin, and ellagic acid were found as radioprotectors as these protected normal cells from gamma radiation-induced injury [32]. Hence, the above experimental evidence suggests the yeast model’s reliability in screening potential radiosensitizers and radioprotectors for clinical use.

3.2. Zebrafish Model System

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos have been proved as a distinct vertebrate model to screen therapeutic agents. It has gained popularity among researchers because of its close genetic relationship to humans, optical clarity in imaging, short embryonic development, and abundance and accessibility of getting embryos within a short time [33]. The transparent visualization of the radiation effect in this model system makes it more convenient to check potential radioprotectors and radiosensitizers [34,35]. For a long time, zebrafish and their embryos have been used to develop xenograft models using established cancer cell lines or combining the tumor and stromal tissues together, which helps to study rapid drug screening [36]. The Zebrafish model helps in the assessment of radioprotector and radiosensitizer from various analyses [10].

Geiger et al. verified the radioprotective effect of amifostine using the zebrafish model. Zebrafishes were used to assess the radiation damage at different developmental stages, and different doses of radiation and amifostine were found to improve the reduction in brain volume and hypocellularity and disorganization of retinal layers than only radiated embryos [37]. McAleer and colleagues documented amifostine as a radioprotector and AG1478, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, as a radiosensitizer using the zebrafish model [38]. Their study revealed that the pre-treatment of 2.5–5 mM AG1478 enhanced embryonic death and significant embryonic disorder along with 4 Gy X-ray radiation at 72 hpf. Another study observed that the treatment of zebrafish embryos with flavopiridol, a cyclin D1 inhibitor, enhanced the radiation sensitivity of zebrafish embryos [39]. In the recent past, one of our studies reported fluvastatin as a potential radiosensitizer using zebrafish embryos [17].

The zebrafish larva xenografts model has emerged as a promising in vivo model to test therapeutic agents for cancer treatment [40]. Zebrafish models have also been used for in vivo radiotherapy studies. For example, using the U251 neuroblastoma zebrafish xenograft model, 4′-bromo-3′nitropropiophenone (NS-123) was reported as a potential radiosensitizer for glioblastoma [41]. Cotreatment with NS-123 and irradiation drastically reduced the numbers of surviving tumor cells in zebrafish xenografts which were successfully reproduced in murine xenograft models. In another similar study, Geiger et al. used U251 human glioma zebrafish xenograft model and reported temozolomide, a DNA-methylating agent as a potent radiosensitizer without affecting zebrafish embryonic development [42]. Gnosa et al. used an embryonic zebrafish xenograft model to confirm the importance of astrocyte elevated gene 1 in the invasion and migration of colon cancer cells as well as radiation-mediated invasion in vivo [43]. Therefore, the accumulated findings emphasize the importance of the zebrafish model in the field of radiation.

Using zebrafish embryos, the radioprotective effect of DF-1 (fullerene nanoparticle) was assessed at systemic and organ-specific levels. Zebrafish embryos for radioprotector screening were further validated [44]. In these recent times, the radioprotective effect of Kelulut honey was validated in zebrafish embryos and radioprotection was conferred by increasing the survival of embryos, protecting organ-specific damage, and exhibiting cellular protection by reducing DNA damage and expression of apoptosis markers [45]. Similarly, the radioprotective effect of polymers was checked on zebrafish embryos in a high throughput screening combining polymer chemistry through Hantzsch’s reaction. The polymers were found to have enormous protective potential, even superior to amifostine, mainly by protecting cellular DNA from radiation damage [46].

3.4. Mouse Model

An in vivo cancer study model should satisfy several notable features of human tumor development or pathophysiology, particularly for radiation therapy studies. [47]. Moreover, tumor initiation steps are essential for experimental feasibility and reproducibility, and this consideration is especially important to observe the impact of radiation on the tumor microenvironment [48]. In a previous study, using a mouse osteosarcoma model, histone deacetylase inhibition was identified as a radiosensitizing strategy in cancer radiotherapy [49]. Doiron et al. using a mouse xenograft model showed that intratumoral release of thymidine analog bromodeoxyuridine (BrdUrd) sensitized cancer toward radiation [50]. Liu et al. compared the radiosensitizing properties of silver-nanoparticle (AgNPs) and gold nanoparticles (AuNPs). They evaluated the radiosensitizing efficacy of AuNPs and AgNPs in an orthotopic mouse brain tumor model using U125 cells [51]. Our study used the UN-KC-6141 syngeneic mouse subcutaneous pancreatic tumor model and found that fluvastatin sensitized pancreatic cancer toward radiation and inhibited radiation-induced fibrosis [17]. Our study advocates that the mouse model can be used not only for radiation modifiers but also to check the side effects of radiation like fibrosis in tumor stroma.

Similarly, several types of research have been undertaken to validate radioprotective candidates in mice models. Kunwar et al. using a mouse model suggested melanin as a potent radioprotector [52]. The study by Feng et al. proclaims the importance of lactoferrin (LF) as a radioprotector using male BALB/c mice. In this study, a significant increase in the survival ratio of mice in the combination group (IR + LF) was noticed when compared to only the radiation group between days 15 and 30 after irradiation. Importantly, combination treatment reduced DNA damage in comparison to only radiated mice [53]. Nair et al. investigated the radioprotective effect of natural polyphenol, and gallic acid (3,4,5-trihydroxy benzoic acid, GA) in Swiss albino mice and found that treatment of GA (100 mg/kg body weight) along with radiation reduced DNA damage in mouse bone marrow cells, splenocytes, and peripheral leukocytes revealed by comet assay [54]. The GA treatment protected the cells from radiation by preventing radiation-induced suppression of the antioxidant enzyme, glutathione peroxidases, and non-protein thiol glutathione [54]. In another study, an increase in the survival of irradiated mice was noticed when the mice were treated orally with 17-dimethylaminoethylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin (17-DMAG, 10 mg/kg) before radiation whereas post-administered 17-DMAG failed to produce such results [55]. Several investigators preferred inbred, hybrid, and outbred mice strains to study the effect of radiation [56]. The effect of radioprotectors and sensitizers has been well characterized in C57BL/6 and C3H/HeN strains of mice model, and both the strains have shown detectable differences in several tissues’ responses post-irradiation and drug treatment [56]. Yet, dozens of other essential mice strains and genetically modified breeds of mice have also been established for this purpose. Other used and important mice models are C3H/HE, C3H/HeJ, BALB/C and, B6D2F1/J [56]. In general, the use of different strains of the mouse can suggest the potential of radioprotectors along with their impact on the immune system. The xenograft model has emerged as a workhorse model in both the industry and research sectors [57]. Although xenograft models are very simple to study, it only satisfies some of the common features of the tumor microenvironment, for which it lacks predictive value for clinical approach [57]. In contrast, genetically engineered mouse models provide many similar features to conduct experiments designed for radiobiological studies. Different in vivo models used for screening of radiosensitizers and radioprotectors are given in Figure 4.

| Figure 4: Different in vivo models used for screening of radiosensitizer and radioprotectors. (a) Yeast cells exposed to radiation in presence of radioresponse modulators facilitates evaluating their effects through estimation of levels of cellular deoxyribonucleic acid damage and cell death, (b) the zebrafish embryos are useful to evaluate effects of radio-response modulators based on their effects on radiation-induced morphological changes and/or viability and (c) experimental tumor bearing mice helps to evaluate radiosensitizers based on their effects on overall tumor growth. [Click here to view] |

Although every model has its advantages and limitations, each has significantly contributed to pre-clinical studies in the radiation filed. Therefore, advancement of preclinical in vitro and in vivo models will assist in the identification and validation of radiosensitizers/radioprotectors that can be used in clinical trials. Different in vitro and in vivo models with their pros and cons are described in Table 1. Several zebrafish models including different strains of normal fishes, genetic mutants, and xenograft models are recently used in radiation studies; however, a reporter based zebrafish model specifically showing the effect of radiation on DNA damage and repair has not been extensively explored yet. Thus, considering the effective use of zebrafishes in radiation studies and the need of molecular level detection of radiation effects, the need of reporter zebrafishes is highly warranted.

Table 1: Advantages and limitations of different models used for the screening of radiosensitizers and radioprotectors

| Model Type | Models | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro model | Organoid/3D culture model | 1. Provides better in vivo tumor architecture and it is a convenient model to study the impact of cellular interaction in radiosensitization/radioprotection comparison to 2D culture systems | 1. Experiments involving organoids to model tumor xenografts need repeated collection of tumor tissues |

| Cell lines | 1. Quick multiplication | 1. Lacks cellular diversity and interaction | |

| In vivo model | Yeast | 1. Simple growth | 1. Presence of a cell wall reduces drug permeability |

| Zebrafish | 1. Low cost for zebrafish culture | 1. Evolutionary distantly related to human | |

| Mouse | 1. Availability of different genetically modified mouse (GEM) models helps to understand the molecular aspect of radiation along with drugs in different genetic backgrounds | 1. The xenograft mouse is not exactly similar to the human tumor microenvironment |

4. CONCLUSION

Radiotherapy is an essential cancer treatment therapy, and it is often combined with cytotoxic drugs to enhance radiation efficacy. The enhancement of radiation efficacy can be achieved by targeting cancer cells and protecting normal cells from radiation effects. Both radiosensitizers and radioprotectors play a key role in the field of radiation biology. Thus, it is essential to identify a potent radiation modifier that needs suitable models. In this review, we have discussed multiple models which have been used to screen radiosensitizers and radioprotectors previously. Every model system has pros and cons depending on the conditions [Table 1]. The models discussed here can be of utmost help to researchers to find out the best model to screen the radiation modifiers. As all the model systems have few drawbacks, searching for a new model for screening radiosensitizer and radioprotector is highly required in the near future.

5. ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Cartoons (cell culture plate, drugs, 96 well plates, zebrafish, yeast, and computers) in Figures 2-4 were created with BioRender.com. Amlan Priyadarshee Mohapatra is a recipient of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) students’ research fellowship, Government of India.

6. AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualisation and review writing: D. Mohapatra, AP. Mohapatra, AK. Sahoo and S. Senapati. Overall supervision: S. Senapati.

7. FUNDING

There is no funding to report.

8. CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no financial or any other conflicts of interest in this work.

9. ETHICAL APPROVALS

This study does not involve experiments on animals or human subjects.

10. DATA AVAILABILITY

All data generated and analyzed are included in this research article.

11. PUBLISHER’S NOTE

This journal remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliation.

REFERENCES

1. Baskar R, Dai J, Wenlong N, Yeo R, Yeoh KW. Biological response of cancer cells to radiation treatment. Front Mol Biosci 2014;1:24. [CrossRef]

2. Biau J, Chautard E, Verrelle P, Dutreix M. Altering DNA repair to improve radiation therapy:Specific and multiple pathway targeting. Front Oncol 2019;9:1009. [CrossRef]

3. Deng L, Liang H, Fu S, Weichselbaum RR, Fu YX. From dna damage to nucleic acid sensing:A strategy to enhance radiation therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:20-5. [CrossRef]

4. Hubenak JR, Zhang Q, Branch CD, Kronowitz SJ. Mechanisms of injury to normal tissue after radiotherapy:A review. Plast Reconstr Surg 2014;133:49e-56. [CrossRef]

5. Fan H, Demirci U, Chen P. Emerging organoid models:Leaping forward in cancer research. J Hematol Oncol 2019;12:142. [CrossRef]

6. Pasch CA, Favreau PF, Yueh AE, Babiarz CP, Gillette AA, Sharick JT,

7. Hubert CG, Rivera M, Spangler LC, Wu Q, Mack SC, Prager BC,

8. Linkous A, Balamatsias D, Snuderl M, Edwards L, Miyaguchi K, Milner T,

9. Park M, Kwon J, Youk H, Shin US, Han YH, Kim Y. Valproic acid protects intestinal organoids against radiation via NOTCH signaling. Cell Biol Int 2021;45:1523-32. [CrossRef]

10. Cosper PF, Abel L, Lee YS, Paz C, Kaushik S, Nickel KP,

11. Jackson SP, Bartek J. The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature 2009;461:1071-8. [CrossRef]

12. Pollard JM, Gatti RA. Clinical radiation sensitivity with DNA repair disorders:An overview. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009;74:1323-31. [CrossRef]

13. McKenna WG, Muschel RJ, Gupta AK, Hahn SM, Bernhard EJ. The RAS signal transduction pathway and its role in radiation sensitivity. Oncogene 2003;22:5866-75. [CrossRef]

14. Toulany M, Rodemann HP. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling as a key mediator of tumor cell responsiveness to radiation. Semin Cancer Biol 2015;35:180-90. [CrossRef]

15. Lacerda L, Reddy JP, Liu D, Larson R, Li L, Masuda H,

16. Chen YA, Shih HW, Lin YC, Hsu HY, Wu TF, Tsai CH,

17. Mohapatra D, Das B, Suresh V, Parida D, Minz AP, Nayak U,

18. Kriegs M, Kasten-Pisula U, Rieckmann T, Holst K, Saker J, Dahm-Daphi J,

19. Myllynen L, Rieckmann T, Dahm-Daphi J, Kasten-Pisula U, Petersen C, Dikomey E,

20. Brach MA, Hass R, Sherman ML, Gunji H, Weichselbaum R, Kufe D. Ionizing radiation induces expression and binding activity of the nuclear factor kappa B. J Clin Invest 1991;88:691-5. [CrossRef]

21. Yamagishi N, Miyakoshi J, Takebe H. Enhanced radiosensitivity by inhibition of nuclear factor kappa B activation in human malignant glioma cells. Int J Radiat Biol 1997;72:157-62. [CrossRef]

22. Veuger SJ, Hunter JE, Durkacz BW. Ionizing radiation-induced NF-kappaB activation requires PARP-1 function to confer radioresistance. Oncogene 2009;28:832-42. [CrossRef]

23. Yang S, Han G, Chen Q, Yu L, Wang P, Zhang Q,

24. Narayan RS, Gasol A, Slangen PL, Cornelissen FM, Lagerweij T, Veldman H,

25. Mattiazzi M, Petrovi?U, Križaj I. Yeast as a model eukaryote in toxinology:A functional genomics approach to studying the molecular basis of action of pharmacologically active molecules. Toxicon 2012;60:558-71. [CrossRef]

26. Botstein D, Chervitz SA, Cherry JM. Yeast as a model organism. Science 1997;277:1259-60. [CrossRef]

27. Huang RX, Zhou PK. DNA damage response signaling pathways and targets for radiotherapy sensitization in cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2020;5:60. [CrossRef]

28. Vaidya PJ, Pasupathy K. Radioprotective action of caffeine:Use of saccharomyces cerevisiae as a test system. Indian J Exp Biol 2001;39:1254-7.

29. Song S, McCann KE, Brown JM. Radiosensitization of yeast cells by inhibition of histone h4 acetylation. Radiat Res 2008;170:618-27. [CrossRef]

30. Pasupathy K, Nair CK, Kagiya TV. Effect of a hypoxic radiosensitizer, AK 2123 (Sanazole), on yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Radiat Res 2001;42:217-27. [CrossRef]

31. Dolling JA, Boreham DR, Brown DL, Raaphorst GP, Mitchel RE. Cisplatin-modification of DNA repair and ionizing radiation lethality in yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat Res 1999;433:127-36. [CrossRef]

32. Nemavarkar P, Chourasia BK, Pasupathy K. Evaluation of radioprotective action of compounds using Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol 2004;23:145-51. [CrossRef]

33. Kishi S, Uchiyama J, Baughman AM, Goto T, Lin MC, Tsai SB. The zebrafish as a vertebrate model of functional aging and very gradual senescence. Exp Gerontol 2003;38:777-86. [CrossRef]

34. Jaafar L, Podolsky RH, Dynan WS. Long-term effects of ionizing radiation on gene expression in a zebrafish model. PLoS One 2013;8:e69445. [CrossRef]

35. Raldúa D, Piña B.

36. Fior R, Póvoa V, Mendes RV, Carvalho T, Gomes A, Figueiredo N,

37. Geiger GA, Parker SE, Beothy AP, Tucker JA, Mullins MC, Kao GD. Zebrafish as a “biosensor“?Effects of ionizing radiation and amifostine on embryonic viability and development. Cancer Res 2006;66:8172-81. [CrossRef]

38. McAleer MF, Davidson C, Davidson WR, Yentzer B, Farber SA, Rodeck U,

39. McAleer MF, Duffy KT, Davidson WR, Kari G, Dicker AP, Rodeck U,

40. Barriuso J, Nagaraju R, Hurlstone A. Zebrafish:A new companion for translational research in oncology. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:969-75. [CrossRef]

41. Lally BE, Geiger GA, Kridel S, Arcury-Quandt AE, Robbins ME, Kock ND,

42. Geiger GA, Fu W, Kao GD. Temozolomide-mediated radiosensitization of human glioma cells in a zebrafish embryonic system. Cancer Res 2008;68:3396-404. [CrossRef]

43. Gnosa S, Capodanno A, Murthy RV, Jensen LD, Sun XF. AEG-1 knockdown in colon cancer cell lines inhibits radiation-enhanced migration and invasion

44. Daroczi B, Kari G, McAleer MF, Wolf JC, Rodeck U, Dicker AP.

45. Adenan MN, Yazan LS, Christianus A, Md Hashim NF, Mohd Noor S, Shamsudin S,

46. Liu G, Zeng Y, Lv T, Mao T, Wei Y, Jia S,

47. Sharpless NE, Depinho RA. The mighty mouse:Genetically engineered mouse models in cancer drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2006;5:741-54. [CrossRef]

48. Moding EJ, Castle KD, Perez BA, Oh P, Min HD, Norris H,

49. Blattmann C, Thiemann M, Stenzinger A, Christmann A, Roth E, Ehemann V,

50. Doiron A, Yapp DT, Olivares M, Zhu JX, Lehnert S. Tumor radiosensitization by sustained intratumoral release of bromodeoxyuridine. Cancer Res 1999;59:3677-81.

51. Liu P, Jin H, Guo Z, Ma J, Zhao J, Li D,

52. Kunwar A, Adhikary B, Jayakumar S, Barik A, Chattopadhyay S, Raghukumar S,

53. Feng L, Li J, Qin L, Guo D, Ding H, Deng D. Radioprotective effect of lactoferrin in mice exposed to sublethal X-ray irradiation. Exp Ther Med 2018;16:3143-8. [CrossRef]

54. Nair GG, Nair CK. Radioprotective effects of gallic acid in mice. Biomed Res Int 2013;2013:953079. [CrossRef]

55. Lu X, Nurmemet D, Bolduc DL, Elliott TB, Kiang JG. Radioprotective effects of oral 17-dimethylaminoethylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin in mice:Bone marrow and small intestine. Cell Biosci 2013;3:36. [CrossRef]

56. Williams JP, Brown SL, Georges GE, Hauer-Jensen M, Hill RP, Huser AK,

57. Castle KD, Chen M, Wisdom AJ, Kirsch DG. Genetically engineered mouse models for studying radiation biology. Transl Cancer Res 2017;6:S900-13. [CrossRef]