1. INTRODUCTION

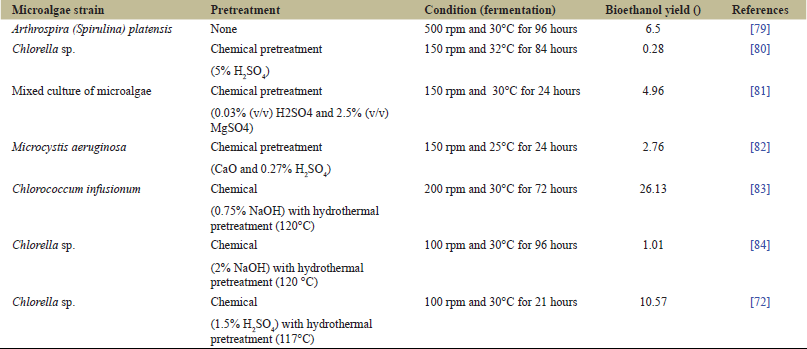

Recently, the interest in the production of fine chemicals and biofuel from algal biomass for partially replacing chemicals from petroleum-based feedstock has gained considerable worldwide attention. The utilization of microalgae biomass also exhibited more advantages over other types of renewable feedstock such as rice straw, plant trunk, leaf, and others. Microalgae contain less lignin and have a simple structure that is less recalcitrant compared to other types of renewable biomass. The other renewable biomass consists of complex biomass structure such as thick lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose which could increase the difficulties of biofuel and fine chemical production [1]. Another advantage of these microalgae is that these microorganisms are microscopic photosynthetic organisms that use sunlight and carbon dioxide (CO2) as key regulators to conduct photosynthesis for their growth which can be integrated for CO2 biosequestration application. In addition, these microorganisms exhibit higher nutrient uptake, which accumulate in cell vacuoles and show a fast growth rate. This makes harvesting time between 1 and 10 days compared to terrestrial plants that require more than 3 months before the biomass can be harvested [2–4]. Moreover, the biomass produced during cultivation contains valuable chemical compounds including lipids, carbohydrates, and proteins. Generally, different types of microalgae strains will synthesize different biochemical metabolites, depending on the cell strains and cultivation condition. Table 1 summarizes the chemical composition distribution in different microalgae strains. Generally, all of these chemical compounds can be converted into other value-added products, such as animal feeds, bulk chemicals, and other bioactive compounds especially for the pharmaceutical industry (Fig. 1).

| Table 1: Chemical composition of different algal species on a dry matter basis (%). [Click here to view] |

The potential of high value-added products synthesized from microalgal biomass is totally dependent on the chemical composition within the microalgae. For instance, microalgae with a high lipid content can be converted into biodiesel. Extracted carbohydrates from microalgal cells can be converted into bioethanol or biobutanol. Furthermore, the low lignin properties in microalgae exhibit an exceptional potential to be used as liquid biofuel feedstock due to the lower harsh pretreatment process. However, to date, researchers are still facing several obstacles that impede the development of the microalgal biorefinery process. The obstacles include a long cultivation period of microalgae to reach the mature state or stationary phase. Low microalgal biomass production, insufficient macromolecule accumulation, immature harvesting technology, pretreatment, and low product yield after the fermentation process could affect the feasibility of the biorefinery process. This comprehensive review discussed current trends and challenges of cultivation conditions and their downstream processing including pretreatment processes, hydrolysis methods, and fermentation conditions that could contribute to the formation of high value-added products. A critical approach was suggested at the end of the review. The focus was more on the strategy for improving carbohydrate accumulation in microalgal biomass. This was to ensure economic feasibility in the biorefinery process for the production of biofuels and fine chemicals.

2. MICROALGAL CARBOHYDRATE BIOREFINERY

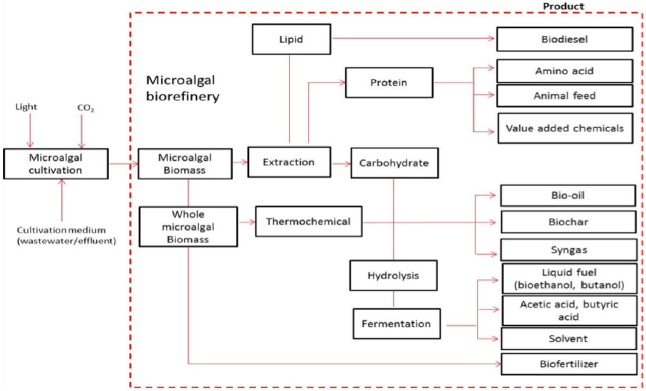

Microalgal biorefinery is the process of synthesizing biofuel and fine chemicals using technology transformation from a single raw material. Chew et al. [12] agreed that this microalgal biorefinery is one of the current approaches that separate biochemical compounds in microalgal biomass into different fractions without damaging other fractions. Generally, the microalgal biomass harvested from cultivation contains three main chemical compounds: lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates [13]. As shown in Figure 2, it is known that each of these compounds has a significant value for a wide range of industries. All these biochemical compounds could be produced through different biochemical pathways.

3. MICROALGAL CARBOHYDRATE

The growth of microalgae and carbohydrate accumulation are typically related to the photosynthesis reaction in microalgal cells [14]. During photosynthesis, microalgae require CO2, sunlight, and oxygen (O2) with the presence of water (H2O). These elements are needed to produce carbohydrate (C6H12O6) and biomass as the final photosynthesis products. The overall photosynthesis reaction described by Meyer [15] is shown in Equation (1):

6CO2 + 12 H2O → C6H12O6 + 6O2 + 6H2O (1)

| Figure 1: Various value-added produced from microalgae biomass. [Click here to view] |

Microalgal carbohydrates are one of the main products produced from microalgal photosynthesis and the carbohydrates can be in various forms. This macromolecule may be in various forms of monomers (i.e., monosaccharides) or polymers (i.e., di-, oligo-, and polysaccharides), depending on the microalgae species. Typically, the polysaccharides found in cyanobacteria and green or red algae are glycogen-type and starch-type polysaccharides, while β-glucan polysaccharides are mainly present in brown algae and diatoms [16]. These formations of polysaccharides in microalgae are of significance for the main structure of the cell wall and energy storage component and act as a food supply for the microalgae cell.

4. CARBOHYDRATE METABOLISM

The accumulation of carbohydrates in microalgae cells involves several main metabolite pathways. Among the pathways involved are glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, citrate cycle, pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), pentose and glucuronate interconversion, starch and sucrose metabolism have been proved that can enhance the carbohydrate biosynthesis in microalgae. All these pathways are important in terms of the contribution to carbohydrate accumulation in microalgal biomass. Figure 3 describes the formation of carbohydrates involving the targeted genes or enzymes and metabolites in microalgae. The enzymes such as α-amylase, isoamylase, pullulanase, β-amylase, and glucoamylase were among the important enzymes that have been reported that play an important role in the carbohydrate biosynthesis in microalgae [17].

| Figure 2: Microalgal technology and conversion process for the microalgal biorefinery. [Click here to view] |

| Figure 3: Carbohydrate biosynthesis pathway in microalgae. [Click here to view] |

According to the study by Kuchitsu et al. [18], the starch biosynthesis in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii was largely affected by the starch synthesis pathway. This can particularly be seen in the especially adenosine diphosphate-glucose-starch (ADP-glucose-starch) synthase enzyme under CO2-rich conditions. The importance of this synthase enzyme was further discussed by Patron and Keeling [19], who reported that this enzyme could enhance the synthesis of plastidic starch, which occurred in the plastid of green microalgae. Subsequently, the study also indicated that the formation of carbohydrates through the starch synthesis pathway was intercorrelated with the glycogen synthesis pathway. Other studies have also indicated the importance of the Embden-Meyerhof pathway and the PPP in converting glucose into disaccharides and polysaccharides, mainly sucrose and starch [20]. Both pathways are notable in microalgal carbohydrate metabolism which has been shown to be responsible for glucose accumulation under light and dark conditions, respectively.

5. STRATEGY TO IMPROVE MICROALGAL CARBOHYDRATE ACCUMULATION

Carbohydrate biosynthesis in microalgal cells can be influenced by several factors. One of the most common factors that contributed to microalgal carbohydrate production is the surrounding cultivation conditions (i.e., abiotic factors). It is essential to determine the optimum cultivation conditions, favorable or merely tolerable for the growth of microalgal species. Cultivation under unfavorable conditions could either increase or decrease the microalgal growth and carbohydrate content [21,22]. The most common cultivation conditions such as the surrounding temperatures, light intensity, pH, and CO2 concentration have reported that these cultivation parameters can significantly influence the microalgal growth and carbohydrate accumulation in microalgal biomass during cultivation [23]. These stress conditions applied toward microalgae have been proven as suitable approaches to enhance microalgal carbohydrate biosynthesis within an appropriate cultivation period and the detailed discussion is explained in the subsequent sections (Fig. 4).

5.1. Cultivation Parameters

5.1.1. Effect of the interaction between pH and CO2 concentration

Initial pH values are an essential parameter that can affect microalgal metabolism and carbohydrate formation in microalgal cells. The optimum pH value range for microalgae is generally between pH 6 and 9 and generally depending on the type of microalgal species. Cultivation of microalgae under the upper pH limit will suppress cell growth by reducing the affinity of microalgae toward the free CO2. This will subsequently lead to a decrease in microalgae photosynthesis rate and growth rate [24,25], whereas the lower limit of pH will induce the acidic environment which could alter the nutrient uptake or stimulate metal toxicity, thus affecting the microalgae growth [26]. The maintaining of the surrounding pH is important to achieve a continued active photosynthesis process under natural daylight [27]. However, the fluctuation of pH values can happen essentially during cultivation especially in the presence of CO2. This phenomenon is due to the presence of CO2 in the cultivation medium that could react with H2O and produce carbonic acid (H2CO3) [28]. Subsequently, H2CO3 decreases the pH value of the cultivation medium to a certain level. This may influence the nutrient uptake and enzyme kinetics involved in microalgal metabolism [29,30].

It was known that the addition of CO2 to the cultivation medium could enhance the microalgae biomass growth and affect the biomass compositions especially carbohydrate and lipid content in the microalgae cell [31]. Maintaining the pH value in the cultivation medium in a photobioreactor using the CO2 manipulation could increase the microalgae productivity and lipid accumulation in the microalgae [32]. The interaction between pH and CO2 concentration has been proved on Nannochloropsis sp. MASCC 11 which exhibited excellent growth and lipid production up to 108.2 and 782.7 mg l−1 on pH 6.00 and 5% CO2 concentration, respectively [33]. The supplementation of CO2 through aeration toward the microalgae culture did not only involve the lipid fraction, while it also involved the carbohydrate fraction in the microalgae biomass through the carbohydrate metabolism pathway. The previous study showed that the increase in the CO2 concentration up to 25% CO2 concentration (v/v) along the microalgae cultivation was increased gradually on the growth rate and carbohydrate content in the Scenedesmus bajacalifornicus BBKLP -07 strain. This increment of both growth rate and carbohydrate content was recorded as 0.16 ± 0.0012 d−1 and 26.19%, respectively, compared to the control treatment (0.04% CO2) [34]. This was due to the fact that CO2 could act as an inorganic carbon source for triggering the microalgae growth and carbon flux flow for carbohydrate synthesis through the photosynthesis process [35].

| Figure 4: The summary diagram impact of different stress factors on the microalgal carbohydrate. [Click here to view] |

Providing the CO2 toward the microalgae during cultivation has been proved to be a good strategy to improve the microalgae growth rate and biochemical accumulation inside the microalgae body [36,37]. However, further increasing the CO2 supplement toward microalgae will lead to a decrease in the cultivation pH value. This phenomenon will result in an adverse effect on the microalgae growth and subsequently affect its biochemical composition accumulation. It can be observed that the cultivation of the Chlorella sp. under 30% CO2 concentration (v/v) could reduce the specific growth rate of microalgae up to 76% compared under normal condition 0.04% CO2 (v/v) [38]. The increment of CO2 concentration beyond the microalgae susceptible limit not only limits the specific microalgae growth but also affects the carbohydrate accumulation in the cell biomass. There was an obvious decrease in carbohydrate composition in Chlorella sp. microalgae by 72.22% when the cultivation was conducted under 15% of CO2 (v/v) concentration.

Under the high CO2 concentration (low pH condition), the microalgae were required to achieve a high-energy demand to drive the proton gradient across the membrane, to stabilize the intracellular pH condition. Then, this energy loss will decrease the photosynthesis rate and affect the carbohydrate accumulation process in microalgae cells [39]. The capability of microalgae in response to the high CO2 concentration is species-dependent [40]. The microalgae that can tolerate the CO2 concentration in between 2% and 5% (v/v) are categorized as CO2-sensitive microalgae, while those that can tolerate between 5% and 20% (v/v) are categorized as CO2-tolerant microalgae. From an industrial perspective, the microalgae that possess the most tolerant and robust characteristics are important to ensure sustainable microalgae bioprocessing and technologies. The robust microalgae strains that can grow under a wide range of pH and high CO2 concentrations are economically feasible for continuous production with low maintenance under large-scale production. Based on the summary above, it clearly indicated that microalgae have a great potential to become one of the CO2 capture and utilization agents. These microalgae can be cultivated in an integrated system with flue gas and the biomass produced can be used as feedstock for microalgae-based products in a biorefinery.

5.1.2. Effect of temperature and light intensity

Another factor that could significantly affect microalgal growth rate and carbohydrate accumulation is the combined effect of light intensity and surrounding temperature. Generally, microalgae cultivation under outdoor conditions could be significantly affected by the light intensity and the surrounding temperature. It is known that light intensity influences the photoadaptation/photoacclimation and photoinhibition processes in microalgal cells. The majority of microalgae are light-saturated under light intensities of 200–400 μmol m−2 s−1. Under the low light intensity, the microalgae will exhibit a slow growth rate due to the inhibition of light harvesting pigments, chlorophyll a and b in that stage. However, the increase of the illuminated light intensity toward the microalgae over the certain threshold value will generate more heat which will raise the temperature. This will cause a decline in damage to the cell and the biochemical composition of microalgae [41].

Generally, the characteristic behavior of the microalgae toward light intensity and environmental temperature could be categorized as heat-sensitive and heat tolerance microalgae [42]. To date, most of the microalgae strains that are isolated nowadays could survive a wide range of light intensities and temperatures through acclimation or adaptation strategies within microalgae metabolism. This combination effect has been observed on Tetradesmus obliquus which performs well on 36°C with 434.75 mol m−2 s−1. The T. obliquus obtained the maximum biomass production up to 115 mg l−1 d−1 under this condition [43]. However, other strains like Chlorella vulgaris exhibited the maximum cell growth up to 1.13 ± 0.04 day−1 when the cultivation was performed under light exposure of 100 μmol m−2 s−1 and temperature of 25 ± 0.5°C [44]. The optimum light intensity and temperature were observed differently from each microalgae strain. Further increased light intensity and surrounding temperature could lead to the effect of photoinhibition. This can be observed when the microalgae were exposed to an intensity of 94.50 μmol m−2 s−1 toward the heat-sensitive microalgae. Low microalgal biomass production was obtained due to the degradation of the D1 protein in the photosynthetic system II in the microalgae [45].

Apart from that, the effect of light intensity and surrounding temperature was also reported that could influence the carbohydrate content in microalgal biomass [46]. It is worth mentioning that, during microalgal photosynthesis, carbohydrates are produced as the final product to be used as an energy source during respiration. Leading to this, a previous study indicated that the optimum light intensity and temperature as 150 μmol m−2 s−1 and 26°C could increase carbohydrate content in Pavlova lutheri up to 66% compared to the normal condition [47]. Nevertheless, it was found that a further increase of light intensity beyond 400 μmol m−2 s−1 appeared to reduce the carbohydrate content to 8% in this microalgae strain. The excessive exposure of light and surrounding temperature on microalgae most probably leads to the degradation of microalgal carbohydrates of which these biomolecules will be transformed into lipids in order to protect microalgal cells from photoinhibition [48].

Therefore, as per the discussion above, it is clearly indicated that the effect of light intensity and surrounding temperature toward microalgae is species-dependent. It is important to select the suitable light intensity and temperature to obtain the maximum biomass production and carbohydrate content in microalgae especially those cultivated under outdoor conditions. On the other hand, selecting the robust strain that is able to withstand a wide range of temperature and light intensity fluctuation with little or nonsignificant effect on growth and carbohydrate productivity is important especially for continuous outdoor cultivation.