4. DISCUSSION

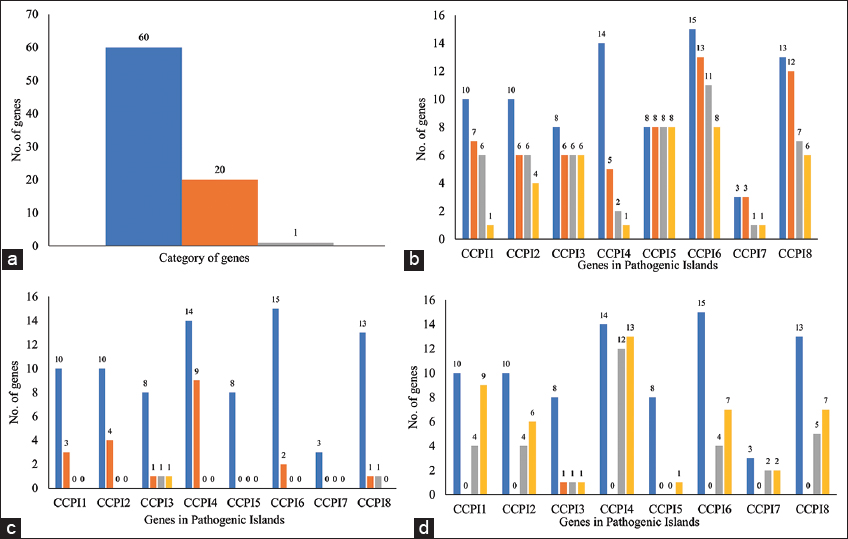

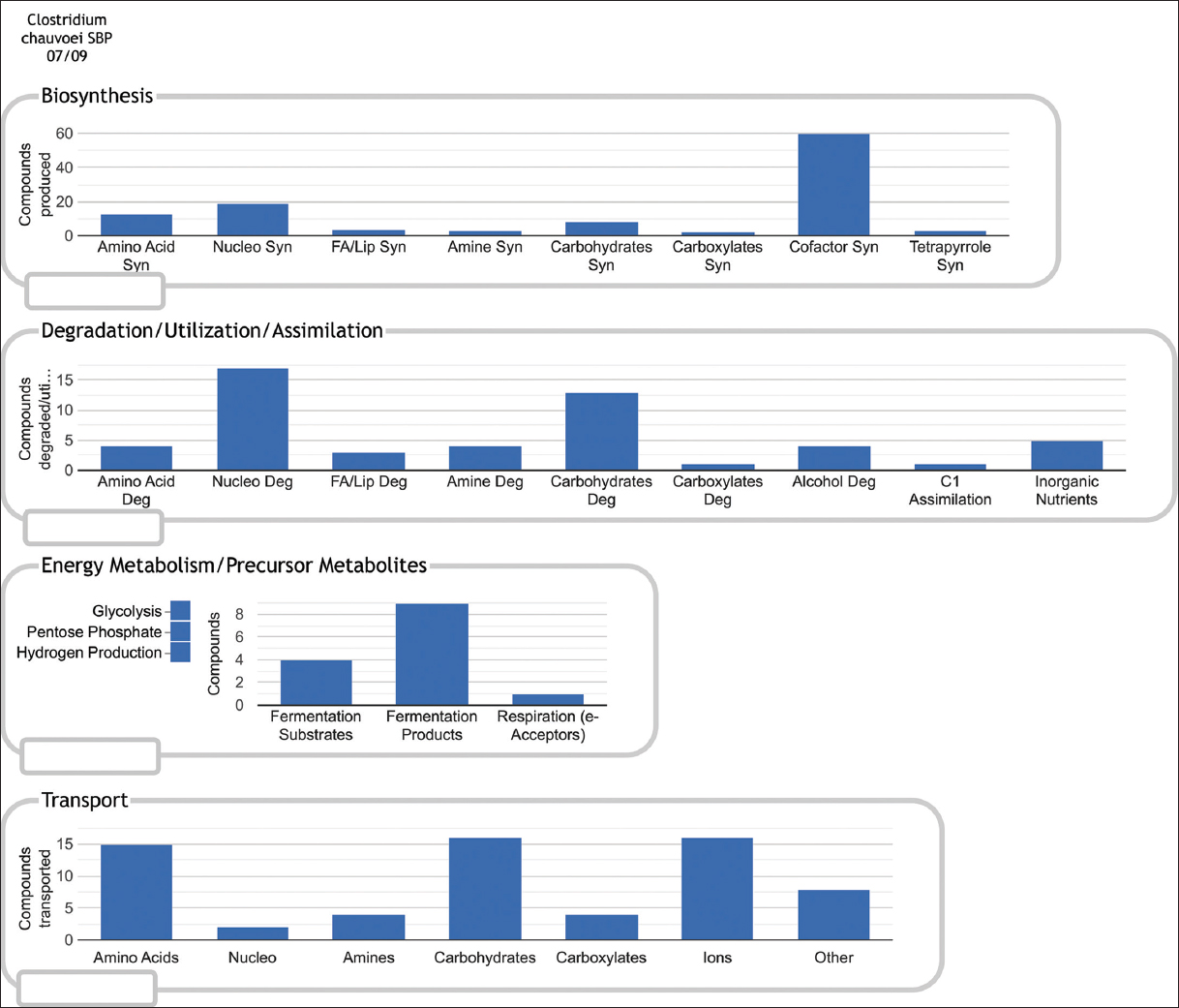

This study aimed to enhance the understanding of C. chauvoei by identifying its PIs and predicting genes potentially linked to virulence and survival. Functional annotation of these genes was performed using homology-based, domain-based, and metabolic category-based approaches to ensure a comprehensive classification. To further investigate the metabolic potential of C. chauvoei, a genome-scale metabolic pathway reconstruction was carried out, and KO IDs derived from metabolic category-based function prediction were mapped onto metabolic pathways. A comparative analysis was then conducted by manually correlating pathways obtained from KEGG and BioCyc Pathway Tools. This allowed for an in-depth evaluation of pathway organization, enzyme annotations, and metabolic variations. This comparison provided insights into key metabolic processes that may contribute to the organism’s adaptation and pathogenicity. Finally, the reconstructed pathways were examined in the context of C. chauvoei’s lifecycle, linking its metabolic capabilities to survival strategies and infection mechanisms. The steps based on the standard tools provided us with the expected results. At the same time, the combinatorial use of these tools in this study linked the genomic islands of the genomes to metabolic pathways. The present section comprehends the understanding of the current study, provides insights, and discusses how the proteins encoded by the PIs help C. chauvoei’s adapt to the situation during pathogenicity.

The genes encoded by these PIs are the genomic data generated in this method, which is helpful for disease management. Disease management is an essential aspect for understanding and controlling a disease. The first step in understanding a disease is to identify the organism causing the disease. However, the bacterial pathogen rapidly evolves and generates highly variable genotypes or isolates. Therefore, identifying the isolate among the group of isolates mainly associated with the disease is essential. Thus, the genomic data can be used as molecular markers that allow us to discriminate different strains within a species and can be applied to disease management.

The proteins encoded by the PIs enhance C. chauvoei’s ability to survive and adapt to diverse environments. They also manage stress responses, effectively sustain metabolic processes, manage energy production, respond to environmental cues, maintain genomic integrity, and acquire beneficial genetic traits. The bacterium’s flexible genetic toolkit, robust energy production, and membrane stabilization systems collectively allow it to persist and evade host defenses. If conditions within the host become unfavorable, some bacterial cells initiate sporulation, forming resilient spores. These spores can withstand environmental stress, ensuring the bacterium’s survival and potential for future transmission.

4.1. Genes Coding for Stress Sensor Proteins Responding to Environmental Cues

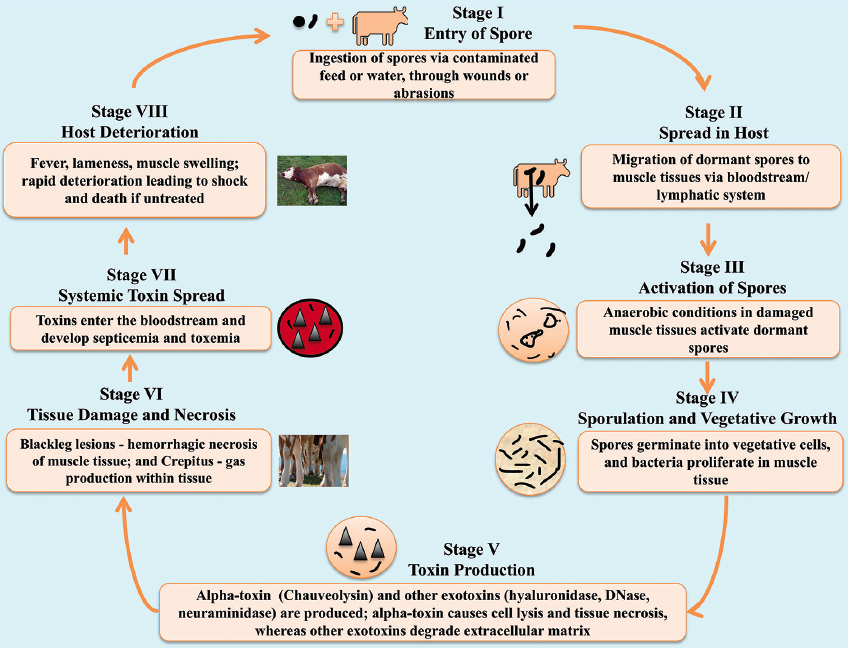

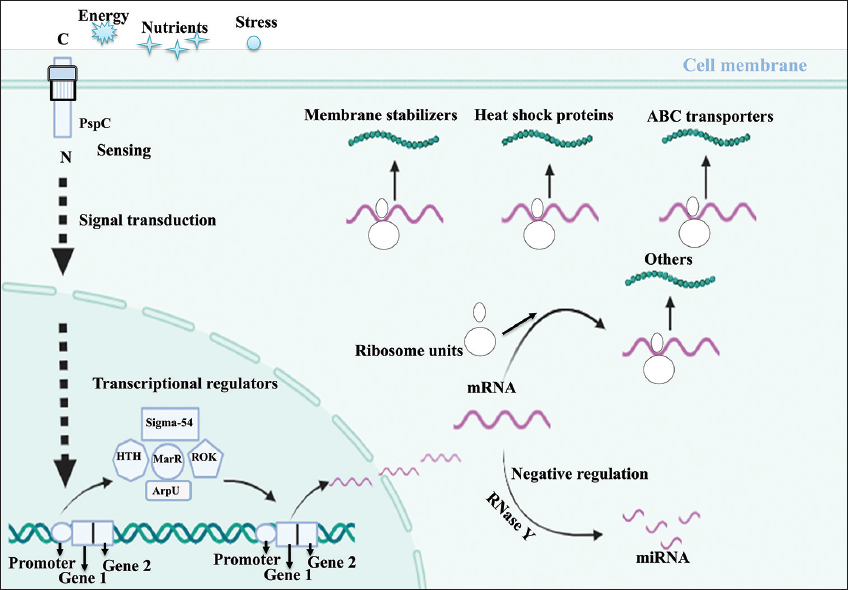

C. chauvoei spores enter a ruminant host, often through ingestion or wound contamination; they encounter a nutrient-rich but hostile environment that initiates spore germination into active bacterial cells. The active bacterial cells are known for having proteins that detect stress due to the acidic and low-oxygen conditions in host tissues. Gram-negative bacteria harbor a highly conserved stress response system known as the envelope stress response (Esr) system, formerly known as phage shock protein (Psp) response system [24] [Figure 4]. The response system senses the signal from the environment and transduces it to the cytoplasm [25]. The Psp systems of E. coli have six proteins, PspA, B, C, D, F, and G. In general, stress mislocalizes protein secretin from the cell envelope due to its dissociation from the chaperone-like pilot protein and also reduces proton motive force. These events help proteins PspB and PspC (CCPI-G10) sense the signals in the extracytoplasmic space and help them bind to PspA, thereby releasing PspF from PspA. The protein PspF activates the promoters of pspG and pspA and subsequently turns on the pspABCDE operon [26]. A rapid sensing of environmental changes marks this transition, and this detection acts as an alert. This initiates a bacterial response to activate RNA polymerase and a number of transcriptional regulators that trigger defense mechanisms, coordinating numerous proteins across several functions. The environment’s hostility becomes apparent, and transcriptional regulators play a critical role in adjusting gene expression to maximize bacterial survival.

4.2. Genes Coding for Transcriptional Regulators to Sustain Metabolic Process

The sigma factor of RNA polymerase (CCPI-G49) is a transcription initiation factor that enables specific binding of RNA polymerase (RNAP) to gene promoters needed to initiate transcription in bacteria. The specific sigma factor used to activate transcription of a given gene will vary, depending on the gene and the environmental signals. RNAP factor sigma-54 is needed to initiate transcription in bacteria in a nitrogen-limited environment [27,28]. The protein PspF also activates the σ54-dependent transcription of the pspABCDE operon [26]. The sigma-54 transcriptional regulator and its interacting counterpart, the Sigma-54-interacting transcriptional regulator (CCPI-G51), add specificity to this response. This helps to focus on genes that help the bacterium function optimally in low-oxygen conditions [Figure 4] [29]. The sigma-54 transcriptional regulator is known for flagellar biosynthesis, motility [30-34], amino acid metabolism [35-37], quorum sensing, biofilm formation, virulence [38-40], and bacterial natural product genes [41].

The helix-turn-helix transcriptional regulator (CCPI-G40, G41) and multiple antibiotic resistance regulator (MarR) family regulators (CCPI-G75), belonging to the family winged helix-turn-helix, activate genes necessary for pathogenicity and stress response [Figure 4]. This helps the bacterium to adapt its metabolism and defense mechanisms to the nutrient-limited, anaerobic conditions within the host. The MarR protein is essential for diverse biological functions, which are crucial to the survival of pathogenic bacteria. The functions include resistance to multiple antibiotics, regulation of virulence-associated traits, virulence genes, hemolytic activity, extracellular protease activity, and motility [42-44]. The signaling molecules or ligands that activate the transcriptional regulator MarR are small phenolic compounds, metal ions, small peptides, and oxidative stress [45]. The repressor, open reading frame, kinase (ROK) family transcriptional regulators (CCPI-G56) are characterized by carbohydrate-sensing domains shared with sugar kinases, and the ROK family transcriptional regulator modulates pathways involved in carbohydrate metabolism, fine-tuning energy production to the available substrates in host tissues [Figure 4].

Bacteria extensively use autolysins to remodel, recycle, and even destroy their cell walls. The autolysin regulatory protein (ArpU) family transcriptional regulator (CCPI-G31) is linked to the regulation of muramidase-2 (peptidoglycan hydrolase-2 or autolysin) [Figure 4]. Bacteria would use ArpU to remodel the cell wall affected by stress. Autolysins may also degrade peptidoglycan to avoid their own recognition by the host’s innate immune system. Collectively, these transcriptional regulators control a network of genes that help C. chauvoei respond to host conditions and establish infection. During this process, the equilibrium between the synthesis and degradation of mRNA in the pathogen is needed. The processing and degradation of mRNAs are initiated by RNase Y (CCPI-G24), an endoribonuclease anchored to the cell membrane [Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure 2]. Exoribonucleases degrade the cleaved products. In many bacteria, these RNases, RNA helicases, and other proteins are organized in a protein complex called the RNA degradosome, which plays an essential role in virulence and pathogenicity [46,47].

4.3. Genes for Managing Energy Production

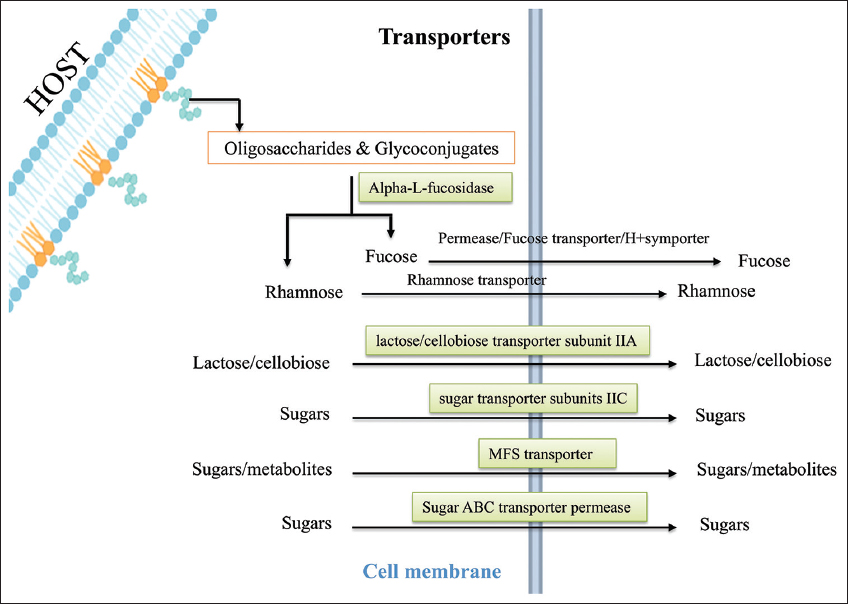

The study identified transcription regulators that activate enzymes, transporters, and energy-related genes that manage energy production. The enzymes such as alpha-L-fucosidase (CCPI-G59) and glycoside hydrolase family 16 protein (CCPI-G60) break down polysaccharides [Figure 5]. Gut microbes produce fucosidases [48-51], cleaving fucose from host glycans (free oligosaccharides and glycoconjugates) to maintain intestinal homeostasis [52,53]. This outcome also ensures additional carbon sources to microbes for energy production, even under oxygen-limited conditions in anaerobic respiration. Transporters are crucial for nutrient uptake, which sustains the bacterium during infection. The major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporter (CCPI-G76) facilitates the uptake of sugars and possibly other metabolites from the host [Figures 4 and 6, Supplementary Figure 3]. FucP and its homologues belonging to the MFS family transported L-fucose across cell membranes in a pH-dependent manner [54-56].

In general, pathogens form communities of microorganisms known as biofilms, and biofilms are protected by extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) made of polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and extracellular DNA [57]. The mature biofilms undergo dispersal, which can be divided into two types: Active and passive dispersal, where active dispersal plays a vital role in the life cycle of a biofilm that contributes to bacterial survival and disease progression. Passive dispersal refers to dispersal by external forces. Active dispersal refers to dispersal triggered by microbes in the biofilm in response to environmental changes such as nutrient starvation, phagocyte challenge, and unfavorable oxygen levels [58]. The enzyme glycoside hydrolase family 16 protein produced by the bacterium may degrade the polysaccharide, poly(1,6)- N-acetyl-d-glucosamine (PNAG), by hydrolyzing β(1,6) glycosidic linkages, forming N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) [59]. GlcNAc then enters the cell and is deacetylated into acetate and GlcN-6-P by GlcNAc-6-phosphate deacetylase, which belongs to the amidohydrolase superfamily (CCPI-G62) [60,61]. Then, GlcN-6-P is used in two main pathways: PG recycling pathway and the glycolysis pathway. Thus, the two enzymes glycoside hydrolase family 16 protein and GlcNAc-6-phosphate deacetylase play a role in bacterial survival and disease progression.

Transporters are crucial for nutrient uptake, which sustains the bacterium during infection. The MFS transporter works alongside the phosphotransferase system (PTS) transporters, facilitating the uptake of sugars and possibly other metabolites from the host [Supplementary Figure 4]. The various PTS transporters include PTS lactose/cellobiose transporter subunit IIA (CCPI-G52), and PTS sugar transporter subunit IIC (CCPI-G55) [Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure 4]. In addition, the putative Lichenan-specific phosphotransferase enzyme IIB component (CCPI-G53) is also identified in the study. Histidine-phosphorylatable phosphocarrier protein (HPr) family phosphocarrier protein (CCPI-G26) acts as a regulator and is essential in the PTS, which transfers sugar molecules across the cell membrane for energy. HPr is present in the cell in the phosphorylated (HPr-P) or non-phosphorylated (HPr) form, depending on the presence or absence of a sugar substrate of the PTS [62,63]. Such sugars, when present, give rise to the dephospho form of the protein due to sugar phosphorylation, but when exogenous PTS sugars are absent, HPr-P should predominate. The concentration of the phosphorylated form of HPr decreases in the presence of a PTS substrate [64,65]. Sugar ABC transporter permease (CCPI-G67) proteins enhance this by efficiently channeling nutrients across the bacterial membrane [Figure 5]. Together, these transporters maximize nutrient intake, helping C. chauvoei thrive in the host’s nutrient-rich but competitive environment.

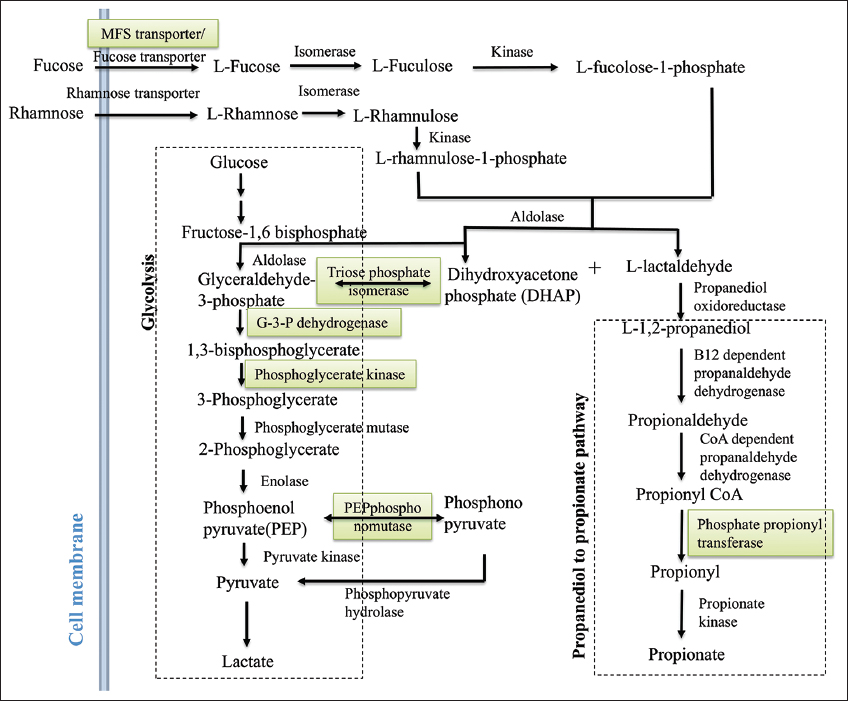

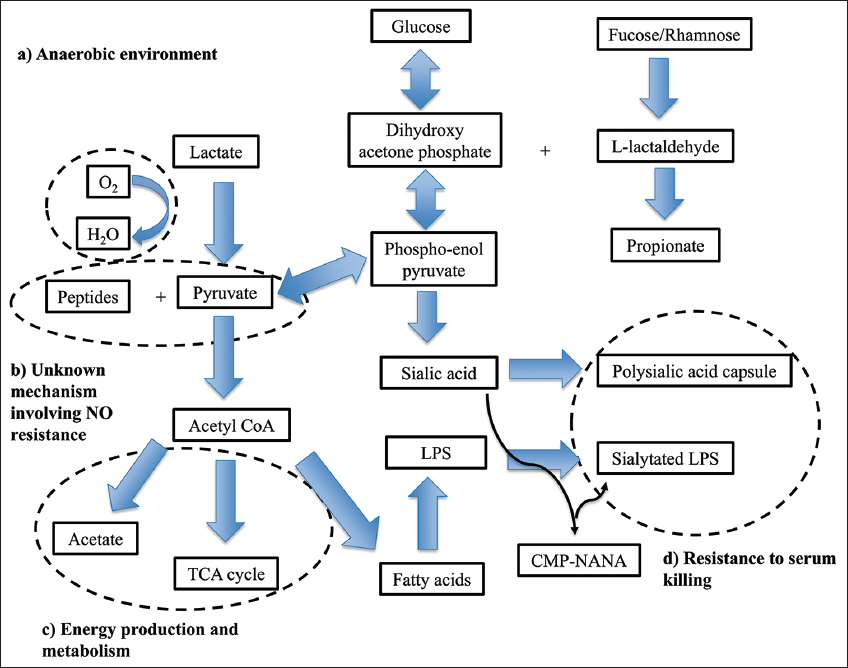

The energy production of C. chauvoei depends on an array of proteins that work collectively to ensure efficient glucose utilization and other anaerobic metabolic pathways. The genes related to the fucose pathway, 1,2-propanediol to propionate pathway, and DHAP to lactate pathway are identified in the study. The fucose pathway starts with fucose and ends with DHAP and L-acetaldehyde [Figure 6]. L-acetaldehyde enters the 1,2-propanediol to propionate pathway, whereas DHAP enters the glycolysis pathway. In the propanediol pathway, the enzyme phosphate propanoyl transferase (CCPI-G11) is identified in the study, and this enzyme catalyzes the reaction of propanoyl-CoA to propanoyl [Figures 6 and 7, Supplementary Figures 5-7]. The study identifies enzymes such as triosephosphate isomerase (CCPI-G45), type I glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (CCPI-G47), phosphoglycerate kinase (CCPI-G46), and 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate-independent phosphoglycerate mutase (CCPI-G44) in the glycolysis pathway. These enzymes catalyze the reactions from DHAP to lactate [Figure 6 and Supplementary Figures 8-12]. In addition, enzyme PEP phosphonomutase (CCPI-G54) catalyzes the conversion of PEP to phosphonopyruvate, and the enzyme phosphonopyruvate hydrolase catalyzes the conversion from phosphonopyruvate to pyruvate [Figure 6]. In contrast, the lactate utilization protein (CCPI-G80) enables C. chauvoei to metabolize lactate, a common byproduct in anaerobic environments within host tissue [Figure 7 and Supplementary Figure 13]. Anaerobic sulfite reductase subunits AsrA (CCPI-G69) and AsrB (CCPI-G70), alongside sulfite reductase subunit C (CCPI-G71), ensure energy production even under oxygen-limited conditions by reducing sulfite to a form usable as hydrogen sulfide in anaerobic respiration [66].

4.4. Genes for Acquiring Beneficial Genetic Traits and Maintaining Genomic Integrity

DNA replication and repair systems are critical as the infection progresses to ensure accurate replication and to counteract DNA damage from host immune defenses. Proteins such as replicative DNA helicase (CCPI-G35) facilitate DNA replication, ensuring continuous bacterial cell division and colony expansion. The recombinase RecA (CCPI-G23) plays an important role in DNA repair through homologous recombination, protecting the bacterium from genotoxic stress imposed by the host immune system [Supplementary Figure 14]. Exonuclease SbcCD subunit D (CCPI-G14) and AAA family ATPase (CCPI-G15) assist in repairing double-strand breaks in DNA and removing damaged nucleotides, respectively, maintaining genome integrity. Meanwhile, the YjjG family nucleotidase (CCPI-G77) helps to remove and recycle damaged or noncanonical pyrimidine bases, preserving DNA and RNA fidelity.

The genetic adaptability of C. chauvoei is based on proteins that promote genome plasticity. The IS256 family transposase (CCPI-G12, G64) and the Rpn family recombination-promoting nuclease (CCPI-G2, G3, G5-7, G9) and tyrosine-type recombinase/integrase (CCPI-G29) enable horizontal gene transfer by allowing DNA segments to integrate into the genome. This capability may enhance virulence or antibiotic resistance, aiding survival under immune pressures. The DDE domain protein (CCPI-G50, G57, G72), DDE-type integrase (CCPI-G66, G68), and other recombinases further promote genetic diversity, allowing the bacterium to adapt to varying conditions within the host and potentially evade immune responses.

During the above reactions or in the TCA cycle, electron transport, DNA repair; flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) exists in four redox states flavin-N(5)-oxide, hydroquinone, quinone, and semiquinone; and is converted between these states by accepting or donating electrons [67]. FAD (Quinone or oxidized form) accepts two electrons and two protons to become FADH2 (hydroquinone form). The oxidation of FADH2 or reduction of FAD by donating or accepting one electron and one proton, respectively, to form semiquinone (FADH·) [68].

REFERENCES

1. Jubb K, Kennedy P, Palmer N. Pathology of Domestic Animals;2012. Available from: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=qjFfJ8pcttMC&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&ots=oC24mbMSGt&sig=KHw3xtP2z5E1H-DfWZB43J1VGaM [Last accessed on 2024 Dec 24].

2. Lange M, Neubauer H, Seyboldt C. Development and validation of a multiplex real-time PCR for detection of Clostridium chauvoei and Clostridium septicum. Mol Cell Probes. 2010;24(4):204-10.[CrossRef]

3. Bagge E, Lewerin SS, Johansson KE. Detection and identification by PCR of Clostridium chauvoei in clinical isolates, bovine faeces and substrates from biogas plant. Acta Vet Scand. 2009;51(1):8.[CrossRef]

4. Rychener L, In-Albon S, Djordjevic SP, Chowdhury PR, Nicholson P, Ziech RE, et al. Clostridium chauvoei, an evolutionary dead-end pathogen. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1054.[CrossRef]

5. Uzal FA, Songer JG, Prescott JF, Popoff MR. Clostridial Diseases in Animals;2016;1-336. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/978111?291 [Last accessed on 2024 Dec 24].[CrossRef]

6. Popoff MR. Clostridial pore-forming toxins:Powerful virulence factors. Anaerobe. 2014;30:220-38.[CrossRef]

7. Useh NM, Nok AJ, Esievo KAN. Pathogenesis and pathology of blackleg in ruminants:The role of toxins and neuraminidase. A short review. Vet Q. 2003;25(4):155-9.[CrossRef]

8. Blackleg in Animals - Infectious Diseases - MSD Veterinary Manual. Available from: https://www.msdvetmanual.com/infectious-diseases/clostridial-diseases/blackleg-in-animals [Last accessed on 2024 Dec 24].

9. Frey J, Johansson A, Bürki S, Vilei EM, Redhead K. Cytotoxin CctA, a major virulence factor of Clostridium chauvoeiconferring protective immunity against myonecrosis. Vaccine. 2012;30(37):5500-5.[CrossRef]

10. Sayers EW, Bolton EE, Brister JR, Canese K, Chan J, Comeau DC, et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(D1):D29-38.[CrossRef]

11. Nammi D, Yarla NS, Chubarev VN, Tarasov VV, Barreto GE, Corolina Pasupulati AM, et al. A systematic in-silico analysis of Helicobacter pyloripathogenic islands for identification of novel drug target candidates. Curr Genomics. 2017;18(5):450-65.[CrossRef]

12. Bertelli C, Laird MR, Williams KP, Simon Fraser University Research Computing Group, Lau BY, Hoad G, et al. IslandViewer 4:Expanded prediction of genomic islands for larger-scale datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(W1):W30-5.[CrossRef]

13. Hsiao W, Wan I, Jones SJ, Brinkman FSL. IslandPath: Aiding detection of genomic islands in prokaryotes. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(3):418-20.[CrossRef]

14. Langille MGI, Hsiao WWL, Brinkman FSL. Evaluation of genomic island predictors using a comparative genomics approach. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9(1):329.[CrossRef]

15. Waack S, Keller O, Asper R, Brodag T, Damm C, Fricke WF, et al. Score-based prediction of genomic islands in prokaryotic genomes using hidden Markov models. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7(1):142.[CrossRef]

16. Besemer J, Borodovsky M. GeneMark: Web software for gene finding in prokaryotes, eukaryotes and viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Web Server issue):W451-4.[CrossRef]

17. Lukashin A, Borodovsky M. GeneMark hmm: New solutions for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26(4):1107-15.[CrossRef]

18. McGinnis S, Madden TL. BLAST: At the core of a powerful and diverse set of sequence analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Web Server issue):W20-5.[CrossRef]

19. Paysan-Lafosse T, Blum M, Chuguransky S, Grego T, Pinto BL, Salazar GA, et al. InterPro in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(D1):D418-27.[CrossRef]

20. Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Morishima K. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG tools for functional characterization of genome and metagenome sequences. J Mol Biol. 2016;428(4):726-31.[CrossRef]

21. Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Sato Y, Ishiguro-Watanabe M, Tanabe M. KEGG: Biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(D1):D672-80.[CrossRef]

22. Kanehisa M, Sato Y. KEGG Mapper for inferring cellular functions from protein sequences. Protein Sci. 2020;29(1):28-35.[CrossRef]

23. Karp PD, Paley SM, Krummenacker M, Kothari A, Midford PE, Subhraveti P, et al. Pathway Tools version 28.0:Integrated software for pathway/genome informatics and systems biology. Brief Bioinform. 2021;22(1):109-26.[CrossRef]

24. Kleine B, Chattopadhyay A, Polen T, Pinto D, Mascher T, Bott M, et al. The three-component system EsrISR regulates a cell envelope stress response in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Mol Microbiol. 2017;106(5):719-41.[CrossRef]

25. Flores-Kim J, Darwin AJ. Activity of a bacterial cell envelope stress response is controlled by the interaction of a protein binding domain with different partners. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(18):11417-30.[CrossRef]

26. Darwin AJ. The phage-shock-protein response. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57(3):621-8.[CrossRef]

27. Gruber TM, Gross CA. Multiple sigma subunits and the partitioning of bacterial transcription space. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57(1):441-66.[CrossRef]

28. Kang JG, Hahn MY, Ishihama A, Roe JH. Identification of sigma factors for growth phase-related promoter selectivity of RNA polymerases from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(13):2566-73.[CrossRef]

29. Yang B, Nie X, Gu Y, Jiang W, Yang C. Control of solvent production by sigma-54 factor and the transcriptional activator AdhR in Clostridium beijerinckii. Microb Biotechnol. 2020;13(2):328-38.[CrossRef]

30. Anderson DK, Ohta N, Wu J, Newton A. Regulation of the Caulobacter crescentus rpoN gene and function of the purified sigma 54 in flagellar gene transcription. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;246(6):697-706.[CrossRef]

31. Arora SK, Ritchings BW, Almira EC, Lory S, Ramphal R. A transcriptional activator, FleQ, regulates mucin adhesion and flagellar gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a cascade manner. J Bacteriol. 1997;179(17):5574-81.[CrossRef]

32. Jiménez-Fernández A, López-Sánchez A, Jiménez-Díaz L, Navarrete B, Calero P, Platero AI, et al. Complex interplay between FleQ, cyclic diguanylate and multiple s factors coordinately regulates flagellar motility and biofilm development in Pseudomonas putida. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):0163142.[CrossRef]

33. Correa NE, Peng F, Klose KE. Roles of the regulatory proteins FlhF and FlhG in the Vibrio cholerae flagellar transcription hierarchy. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(18):6324-32.[CrossRef]

34. Martinez RM, Dharmasena MN, Kirn TJ, Taylor RK. Characterization of two outer membrane proteins, FlgO and FlgP, that influence Vibrio cholerae motility. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(18):5669-79.[CrossRef]

35. Shao X, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Zhu M, Yang P, Yuan J, et al. RpoN-dependent direct regulation of quorum sensing and the type VI secretion system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Bacteriol. 2018;200(16):00205-18.[CrossRef]

36. Matsuyama BY, Krasteva PV, Baraquet C, Harwood CS, Sondermann H, Navarro MVAS. Mechanistic insights into c-di-GMP-dependent control of the biofilm regulator FleQ from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(2):E209-18.[CrossRef]

37. Lloyd MG, Lundgren BR, Hall CW, Gagnon LBP, Mah TF, Moffat JF, et al. Targeting the alternative sigma factor RpoN to combat virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):12615.[CrossRef]

38. Hayrapetyan H, Tempelaars M, Nierop Groot M, Abee T. Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579RpoN (Sigma 54) is a pleiotropic regulator of growth, carbohydrate metabolism, motility, biofilm formation and toxin production. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):0134872.[CrossRef]

39. Arai H, Hayashi M, Kuroi A, Ishii M, Igarashi Y. Transcriptional regulation of the flavohemoglobin gene for aerobic nitric oxide detoxification by the second nitric oxide-responsive regulator of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(12):3960-8.[CrossRef]

40. Weiner L, Brissette JL, Model P. Stress-induced expression of the Escherichia coli phage shock protein operon is dependent on sigma 54 and modulated by positive and negative feedback mechanisms. Genes Dev. 1991;5(10):1912-23.[CrossRef]

41. Ma M, Welch RD, Garza AG. The s54 system directly regulates bacterial natural product genes. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):4771.[CrossRef]

42. Grove A. Regulation of metabolic pathways by MarR family transcription factors. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2017;15:366-71.[CrossRef]

43. Weatherspoon-Griffin N, Wing HJ. Characterization of SlyA in Shigella flexneri identifies a novel role in virulence. Infect Immun. 2016;84(4):1073-82.[CrossRef]

44. Li Z, Li W, Lu J, Liu Z, Lin X, Liu Y. Quantitative proteomics analysis reveals the effect of a MarR family transcriptional regulator AHA_2124 on Aeromonas hydrophila. Biology (Basel). 2023;12(12):1473.[CrossRef]

45. Grove A. MarR family transcription factors. Curr Biol. 2013;23(4):R142-3.[CrossRef]

46. Matos RG, Casinhas J, Bárria C, Dos Santos RF, Silva IJ, Arraiano CM. The role of ribonucleases and sRNAs in the virulence of foodborne pathogens. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:910.[CrossRef]

47. Jester BC, Romby P, Lioliou E. When ribonucleases come into play in pathogens:A survey of Gram-positive bacteria. Int J Microbiol. 2012;2012:592196.[CrossRef]

48. Wu H, Rebello O, Crost EH, Owen CD, Walpole S, Bennati-Granier C, et al. Fucosidases from the human gut symbiont Ruminococcus gnavus. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78(2):675-93.[CrossRef]

49. Sakurama H, Tsutsumi E, Ashida H, Katayama T, Yamamoto K, Kumagai H. Differences in the substrate specificities and active-site structures of two a-L- fucosidases (glycoside hydrolase family 29) from Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2012;76(5):1022-4.[CrossRef]

50. Sela DA, Garrido D, Lerno L, Wu S, Tan K, Eom HJ, et al. Bifidobacterium longum subsp. ATCC 15697 a-Fucosidases are active on fucosylated human milk oligosaccharides. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78(3):795-803.[CrossRef]

51. Kostopoulos I, Elzinga J, Ottman N, Klievink JT, Blijenberg B, Aalvink S, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila uses human milk oligosaccharides to thrive in the early life conditions in vitro. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):14330.[CrossRef]

52. Pickard JM, Maurice CF, Kinnebrew MA, Abt MC, Schenten D, Golovkina TV, et al. Rapid fucosylation of intestinal epithelium sustains host-commensal symbiosis in sickness. Nature. 2014;514(7524):638-41.[CrossRef]

53. Lei C, Sun R, Xu G, Tan Y, Feng W, McClain CJ, et al. Enteric VIP-producing neurons maintain gut microbiota homeostasis through regulating epithelium fucosylation. Cell Host Microbe. 2022;30(10):1417-34.8.[CrossRef]

54. Dang S, Sun L, Huang Y, Lu F, Liu Y, Gong H, et al. Structure of a fucose transporter in an outward-open conformation. Nature. 2010;467(7316):734-8.[CrossRef]

55. Pao SS, Paulsen IT, Saier MH. Major facilitator superfamily. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62(1):1-34.[CrossRef]

56. Law CJ, Maloney PC, Wang DN. Ins and outs of major facilitator superfamily antiporters. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2008;62:289-305.[CrossRef]

57. Flemming HC, Wingender J. The biofilm matrix. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8(9):623-33.[CrossRef]

58. Fleming D, Rumbaugh KP. Approaches to dispersing medical biofilms. Microorganisms. 2017;5(2):15.[CrossRef]

59. Baker P, Hill PJ, Snarr BD, Alnabelseya N, Pestrak MJ, Lee MJ, et al. Exopolysaccharide biosynthetic glycoside hydrolases can be utilized to disrupt and prevent Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Sci Adv. 2016;2(5):1501632.[CrossRef]

60. Plumbridge J. An alternative route for recycling of N-acetylglucosamine from peptidoglycan involves the N-acetylglucosamine phosphotransferase system in Escherichia coli.JBacteriol. 2009;191(18):5641-7.[CrossRef]

61. Amidohydrolase family (PF01979) - Pfam entry - InterPro. Available from: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/entry/pfam/PF01979 [Last accessed on 2024 Dec 24].

62. Kim HM, Park YH, Yoon CK, Seok YJ. Histidine phosphocarrier protein regulates pyruvate kinase A activity in response to glucose in Vibrio vulnificus. Mol Microbiol. 2015;96(2):293-305.[CrossRef]

63. Deutscher J, AkéFMD, Derkaoui M, ZébréAC, Cao TN, Bouraoui H, et al. The bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase system:Regulation by protein phosphorylation and phosphorylation-dependent protein-protein interactions. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2014;78(2):231-56.[CrossRef]

64. Postma PW, Lengeler JW, Jacobson GR. Phosphoenolpyruvate:Carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems of bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57(3):543-94.[CrossRef]

65. Hogema BM, Arents JC, Bader R, Eijkemans K, Yoshida H, Takahashi H, et al. Inducer exclusion in Escherichia coli by non-PTS substrates:The role of the PEP to pyruvate ratio in determining the phosphorylation state of enzyme IIAGlc. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30(3):487-98.[CrossRef]

66. Parey K, Warkentin E, Kroneck PMH, Ermler U. Reaction cycle of the dissimilatory sulfite reductase from Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Biochemistry. 2010;49(41):8912-21.[CrossRef]

67. Teufel R, Agarwal V, Moore BS. Unusual flavoenzyme catalysis in marine bacteria. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2016;31:31-9.[CrossRef]

68. Teufel R, Miyanaga A, Michaudel Q, Stull F, Louie G, Noel JP, et al. Flavin-mediated dual oxidation controls an enzymatic Favorskii-type rearrangement. Nature. 2013;503(7477):552-6.[CrossRef]

69. Kikuchi S, Shibuya I, Matsumoto K. Viability of an Escherichia coli pgsA null mutant lacking detectable phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(2):371-6.[CrossRef]

70. Penzo M, Guerrieri A, Zacchini F, TreréD, Montanaro L. RNA pseudouridylation in Physiology and medicine:For better and for worse. Genes (Basel). 2017;8(11):301.[CrossRef]

71. Davis FF, Allen FW. Ribonucleic acids from yeast which contain a fifth nucleotide. J Biol Chem. 1957;227(2):907-15.[CrossRef]

72. Pickerill ES, Kurtz RP, Tharp A, Guerrero Sanz P, Begum M, Bernstein DA. Pseudouridine synthase 7 impacts Candida albicans rRNA processing and morphological plasticity. Yeast. 2019;36(11):669-77.[CrossRef]

73. Huang L, Ku J, Pookanjanatavip M, Gu X, Wang D, Greene PJ, et al. Identification of two Escherichia coli pseudouridine synthases that show multisite specificity for 23S RNA. Biochemistry. 1998;37(45):15951-7.[CrossRef]

74. Kowalak JA, Bruenger E, Hashizume T, Peltier JM, Ofengand J, McCloskey JA. Structural characterization of U*-1915 in domain IV from Escherichia coli 23S ribosomal RNA as 3-methylpseudouridine. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24(4):688-93.[CrossRef]

75. Ero R, Peil L, Liiv A, Remme J. Identification of pseudouridine methyltransferase in Escherichia coli. RNA. 2008;14(10):2223-33.[CrossRef]

76. Purta E, Kaminska KH, Kasprzak JM, Bujnicki JM, Douthwaite S. YbeA is the m3Psi methyltransferase RlmH that targets nucleotide 1915 23S rRNA. RNA. 2008;14(10):2234-44.[CrossRef]

77. Jiang T, Gao C, Ma C, Xu P. Microbial lactate utilization:Enzymes, pathogenesis, and regulation. Trends Microbiol. 2014;22(10):589-99.[CrossRef]