4. DISCUSSION

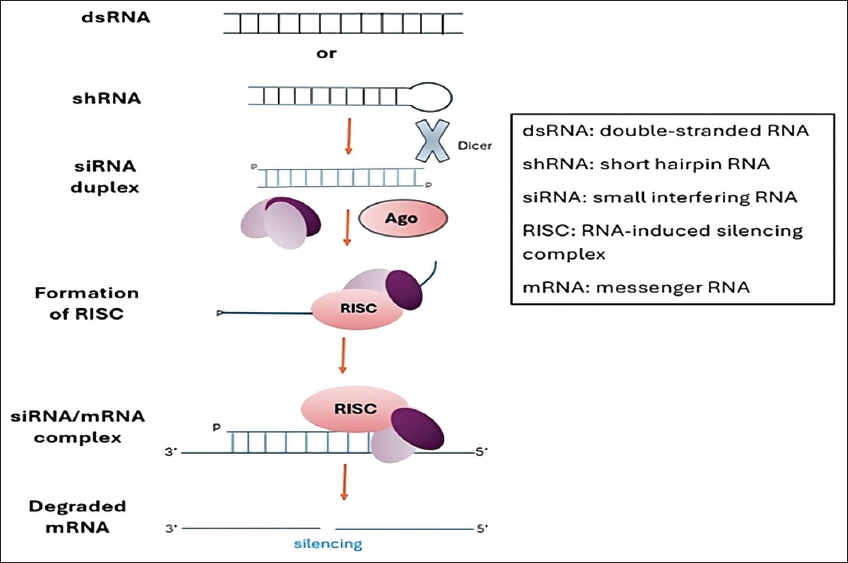

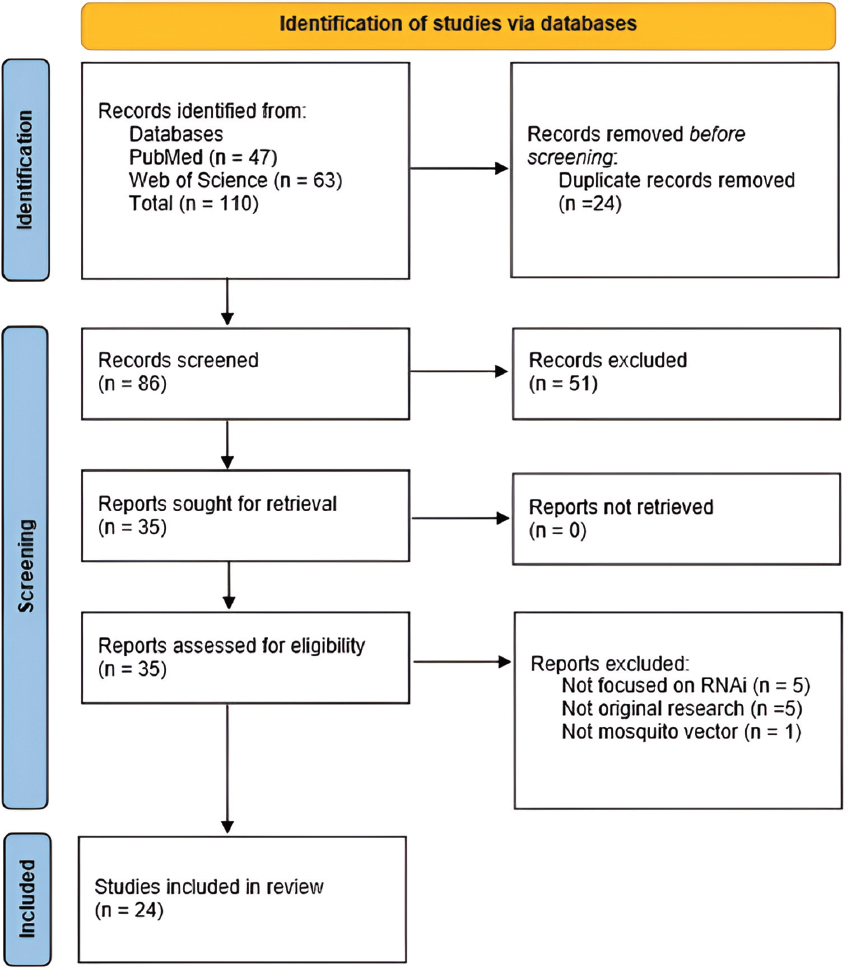

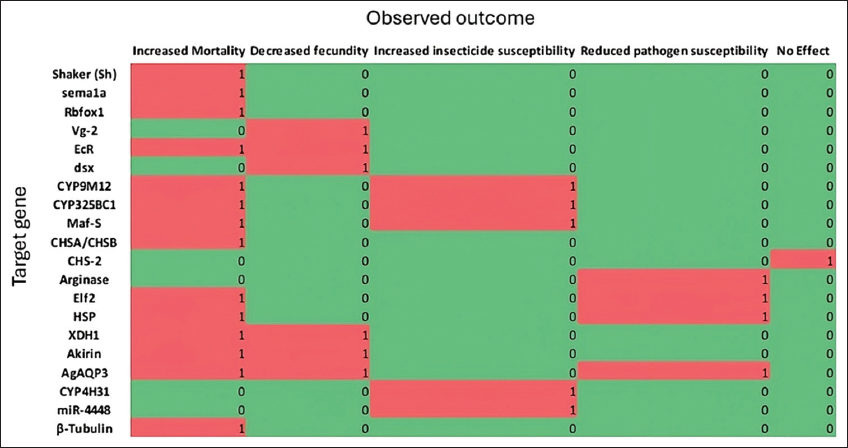

RNAi is an innovative approach in the field of functional genomics research and has been used to control pests by silencing specific genes. When genes vital to the survival of mosquitoes are silenced, it can lead to increased mortality of the mosquito species. Researchers have employed RNAi to suppress mosquito genes to determine the impact of gene silencing on the mosquitoes [7]. In this review, we examined RNAi as an emerging technology with potential applications as a novel vector control agent. From the studies, it can be deduced that RNAi can be applied to disrupt various physiological processes within mosquito vectors. Laboratory experimental analyses were used by most of the studies to silence genes responsible for immune regulation, neural function, xenobiotic detoxification, and reproduction. Silencing of these genes compromised mosquito survival, reduced fecundity, lowered susceptibility to pathogen infection, impaired pathogen development, and increased insecticide susceptibility [8,18,22]. From the studies, the strongest impact of silencing targeted genes in various mosquito species was increased mortality. Silencing the AgAQP3 gene resulted in increased mortality, decreased fecundity, and reduced pathogen susceptibility [Figure 3], suggesting this gene as a good target for future RNAi interventions.

The majority of the studies analyzed showed success in targeting specific genes across the three developmental stages of mosquitoes. Research on neural genes, particularly Shaker, sema1a, and Rbfox1, showed that silencing them induced mortality in both larvae and adult mosquitoes [Figure 3], demonstrating their important roles in mosquito survival [20,25,26,42]. Similarly, cytochrome P450 genes, involved in insecticide detoxification, such as CYP9M12, CYP325BC1, and the transcription factor Maf-S, were effectively silenced using interfering RNA. This process ultimately resulted in increased insecticide susceptibility [30,31]. In addition to the identified gene targets, reproductive and immune regulatory genes such as Vg-2, EcR, dsx, Elf2, and HSP were also targeted by interfering RNA, resulting in reduced fecundity, impaired oogenesis, decreased pathogen susceptibility, and increased mortality in mosquito vectors [27,28,35,43,44]. These studies have revealed that RNAi can be applied not only to impair mosquito development but also to decrease their chances of being infected by various pathogens.

4.1. Interfering RNA Delivery Methods

The most widely used method of dsRNA delivery remains the microinjection method, which exhibits excellent precision and consistency. However, this technique has several drawbacks, such as the requirement for skilled personnel and notable differences in injection efficiency across species. Variations in key factors such as needle choice, injection site, optimal volume, dsRNA concentration, and amount supplied can influence the final outcome [18]. In addition, this method is laborious and limited in field applications. Next was the oral administration approach, often involving genetically engineered microorganisms such as S. cerevisiae (yeast), E. coli (bacteria), and Chlamydomonas (microalgae) as delivery agents. The outcome of this method yielded mixed results. Studies by Mysore et al. [20,25,26], Lopez et al. [33], and Fei et al. [38] concluded that although engineered microbes could successfully express dsRNA to silence specific genes, issues such as degradation, instability, and variability in dsRNA uptake were frequently reported, and this limited the consistency of oral delivery systems. Table 6 presents comparative characteristics of microbial RNAi delivery platforms for mosquito control. Despite these challenges, several past studies reported significant successes in gene silencing. However, a recent study by Prates et al. [37] found minimal knockdown effects and no notable larval mortality when using oral and soaking methods to deliver dsRNA targeting multiple neural and structural genes. Similarly, Zhang et al. [34] found that silencing midgut chitin synthesis genes disrupted the peritrophic membrane but did not cause larval death, indicating variable effectiveness depending on gene targets and delivery methods. Soaking, mainly used in larvae and pupae, showed varying success rates. For example, one study reported that soaking recently molted pupae in dsRNA targeting the cytochrome gene had minimal impact on pupal mortality and an even lesser effect on older pupae [40]. This reveals that although soaking is a relatively cheaper and easier method, its efficiency is largely dependent on the developmental stage of the mosquito vector.

Table 6: Comparative characteristics of microbial RNAi delivery platforms for mosquito control.

| Intervention | RNAi expression | Cost | Biological safety | Stability | Field deployability | Reference |

|---|

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | Moderate | High (potentially due to alga culture) | Limited biosafety evaluation | Moderate (light sensitivity) | Limited due to aquatic delivery | [48] |

| Escherichia coli | High | Low | Safety concern exists | Moderate due to sensitivity to ultraviolet and temperature | Moderate to low, as it requires a cold chain | [49] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Moderate | Moderate | Generally regarded as safe | High | High (wide mode of delivery) | [50] |

RNAi: RNA interference

Innovative delivery systems such as ATSBs-dsRNA and transgenic RNAi expression systems have been explored in some studies. Williams et al. [41] and Mysore et al. [25] found that these methods demonstrated high effectiveness in inducing gene knockdown and mosquito mortality. However, to fully adopt these approaches, thorough field validation, biosafety assessments, including their impact on non-target organisms, and regulatory measures are necessary before real-world implementation.

4.2. Emerging Advances in Gene Silencing Technologies for Mosquito Vector Control

Synthetic biology tools are transforming mosquito control by enabling precise, multifaceted strategies that address the limitations of traditional methods. RNAi, CRISPR-based systems (including CRISPRi and gene drives), nanocarriers, and RNA stabilization techniques are increasingly combined to develop sustainable molecular solutions against vector-borne diseases. CRISPR/Cas technologies have advanced research in insect biology and vector control, facilitating heritable, population-wide modifications. In this framework, CRISPRi provides non-cleavage, reversible gene repression through dCas9-sgRNA complexes that silence genes without making permanent changes. Although research on CRISPRi in mosquitoes is limited, successful applications of dCas9 in A. aegypti indicate potential for reversible gene regulation [45].

4.2.1. Nanoparticle delivery systems

RNAi has great potential in modern vector control strategies, but its effectiveness is limited by the rapid degradation of dsRNA in the gut. The instability of naked RNA molecules when exposed to heat, RNases, or ultraviolet radiation has led to growing interest in nanoparticle-based delivery systems [46]. Nanoparticles are increasingly being used in medicine for drug delivery and siRNA therapy [24]. They are non-microbial methods for delivering RNAi triggers, particularly dsRNA, that have found application in mosquito vector control.

4.2.1.1. Chitosan nanoparticles

Chitosan, a biodegradable material, has been extensively used for delivering drugs; however, it has also found recent applications in dsRNA delivery in insects [24,47]. It protects dsRNA from degradation by nucleases and maintains stability in the high pH of the insect gut, and also possesses antimicrobial properties that prevent the degradation of dsRNA by microorganisms [48]. The use of chitosan nanoparticles (CNP) complexed with dsRNA to induce RNAi in mosquito larvae was pioneered by Zhang et al. [49]. This complex is formed through the self-assembly of positively charged chitosan amino acids and negatively charged dsRNA phosphate groups. When incorporated into mosquito food, CNP/dsRNA successfully downregulated chitin synthase genes in A. gambiae [49]. Research by Dhandapani et al. [50] demonstrated that cross-linking chitosan with sodium tripolyphosphate increased the efficacy of CNP binding, thereby enhancing the stability and delivery of dsRNA. This ultimately led to improved gene knockdown and reduced larval mortality. The function of several genes, including wing-development vestigial genes, cadherin, and many more, has been extensively studied in mosquito research using RNA interference (RNAi) via nanoparticles [24].

4.2.1.2. Other nanoparticles and liposomes

Other nanoparticles, such as silica nanoparticles (SNPs) and carbon quantum dots (CQDs), have been investigated as dsRNA delivery vehicles in addition to chitosan. According to comparative research, CQDs caused more gene silencing and larval mortality than CNP and SNPs, presumably due to their quick diffusion throughout the insect body and stability in the extremely high pH of the mosquito gut [51].

Double-stranded RNA has also been effectively delivered to mosquito larvae through liposomes, a lipid form of nanoparticles; preliminary research has shown that these particles can downregulate genes such as MAPK p38 in A. aegypti larvae [52]. Liposomes may decrease dsRNA breakdown and improve distribution via gut cells, but they may also show some larval toxicity based on exposure duration and concentration [24].

4.2.2. Symbiont-based delivery system

A promising alternative is the microbial expressivity of RNAi delivery compared to synthetic and injection-based methods. Notably, biologically engineered S. cerevisiae expressing shRNAs against Notch pathway genes has been reported to increase the mortality of larvae of both A. gambiae and A. aegypti [25]. Similarly, designed E. coli can serve as a chassis for synthesizing dsRNA and potentially provide a scalable and affordable strategy for silencing target genes in mosquitoes. The dsRNA produced can induce RNAi effects in the target organisms [53]. Specifically, a study by Whitten and colleagues in 2016 showed that genetically modified gut symbionts could stably colonize insects, establish long-term bacterial expression of dsRNA, and generate a strong gene knockdown resulting in phenotypic control [54]. Rhodococcus rhodnii in Rhodnius prolixus and Pantoea agglomerans in Frankliniella occidentalis were engineered to target vital genes, such as vitellogenins and tubulin. Their results showed a notable decrease in fecundity and survival, and the modified bacteria remained within the insect gut and could transmit horizontally. These characteristics also demonstrate how symbiont-based RNAi has the potential to address major limitations of traditional microbial platforms, such as the temporary expression of dsRNA and challenges with outdoor delivery. Although symbiont-based RNAi has not yet been widely used in mosquitoes, its success in non-model vectors with culturable symbionts suggests it can be easily adapted to these insect hosts, targeting Aedes or Anopheles mosquitoes, and warrants further research in the future.

4.3. Comparative Analysis: RNAi vs. CRISPR-Based Silencing

RNAi operates post-transcriptionally via siRNA-RISC-guided mRNA degradation, producing temporary knockdown effects [55,56]. CRISPR/Cas9-based editing permanently modifies DNA, enabling long-term population suppression or replacement through gene drives. CRISPRi, in contrast, offers precise, reversible repression without DNA cleavage. RNAi and CRISPRi suit reversible research and interventions, whereas CRISPR/Cas9 editing underpins durable, heritable strategies [57]. Each approach faces off-target risks and potential resistance evolution, necessitating ongoing molecular optimization and field monitoring.

4.4. Bioengineering Advances for RNA Stabilization

RNA’s inherent fragility limits its utility in vector control. Bioengineering efforts focus on chemical modifications (e.g., m6A, pseudouridylation, and 2′-fluorination), structural engineering (e.g., RNA nanostructures and duplexes), and protective reagents or matrices to block RNase activity and prevent degradation [58]. Nanoparticles also play a dual role, facilitating delivery while stabilizing RNA molecules. These innovations not only enhance RNAi durability in mosquitoes but also have broader implications for RNA therapeutics, including mRNA vaccines and gene therapies [59].

4.5. Gaps and Implications for Vector Control

RNAi has shown several promising outcomes from laboratory and semi-field trials, but despite that, some limitations must be addressed before it can be fully employed as a vector control tool.

RNA instability and off-target effects: RNA molecules used for this process can become unstable and prone to degradation, either by nucleases present in the mosquito’s gut or in its environment. This is especially true for oral and soaking methods of delivery [24,37]. This problem can be solved by employing the novel and emerging tools and technologies discussed earlier

Lack of standardization: There was variability in mosquito strains, developmental stages, gene targets, dsRNA doses, and delivery methods across all the analyzed studies. This complicates drawing broad conclusions, comparing efficacy, or designing protocols for RNAi research. These variations could also be the cause of the differences in gene knockdown efficiency and mortality outcomes

Limited field validation: Only very few studies have carried out semi-field trials [20,26,38]. None of the studies reported large-scale field deployment, but most have only been validated in the laboratory and under laboratory conditions. This presents a major translational gap between laboratory research and large-scale field deployment

Regulatory and biosafety concerns: This is particularly important when dealing with transgenic RNAi systems and microbial dsRNA delivery methods. Regulatory agencies, such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, emphasize case-by-case risk assessments that consider dsRNA stability, sequence specificity, exposure pathways, and impacts on non-target organisms. International agreements, such as the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety, also guide the use of genetically modified organisms, which may apply to microbial-based RNAi delivery. While concerns regarding environmental safety, non-target effects, and public acceptance will be raised, available evidence indicates that dsRNA molecules are rapidly degraded in the soil and digestive systems, and their high sequence specificity minimizes unintended effects. Many studies have reported that RNAi is a safe control tool with minimal effects on non-target organisms and the environment [8,19,20].

Despite promising results, the reproducibility of RNAi outcomes varies across mosquito studies. Several studies have reported variable knockdown efficiency and inconsistent mortality effects, even when targeting similar genes [37]. Methodological flaws, such as inconsistent dsRNA doses and a lack of standardized delivery protocols, further hinder comparability between studies. Moreover, most of the existing studies on RNAi are laboratory-based, creating a translational gap that needs to be addressed to advance RNAi as a reliable and scalable vector control strategy.

4.6. Future Directions

The main areas to focus on in the effort to implement RNAi as a vector control agent include finding safe and cost-effective ways to stabilize the iRNA species before they reach their target mRNA, identifying and standardizing the optimal dose of dsRNA that is highly effective in gene silencing, and that is also safe for the environment and non-target organisms. Biotechnological advancements, such as the bio-design of interfering RNA species that can be reproducible and have predictable outcomes, as well as the development of an RNAi toolkit that would consist of customizable promoters, silencing sequences, and delivery agents, would allow for easy prototyping and lead to greater efficiency and scalability of RNAi-based control. In addition, machine learning software can be used to predict gene targets by mining genomics and transcriptomics data. This would largely improve specificity and knockdown success rate [60].

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. Vector-Borne Diseases. World Health Organization;2017. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/vector-borne-diseases [Last accessed on 2025 Jun 13].

2. Adegbite G, Edeki S, Isewon I, Dokunmu T, Rotimi S, Oyelade J, et al. Investigating the epidemiological factors responsible for malaria transmission dynamics. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2022;993(1):012008.[CrossRef]

3. Olatunbosun-Oduola A, Abba E, Adelaja O, Taiwo-Ande A, Poloma-Yoriyo K, Samson-Awolola T. Widespread report of multiple insecticide resistance in Anopheles gambiae s.l. Mosquitoes in Eight Communities in Southern Gombe, North-Eastern Nigeria. J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2019;13(1):50-61.[CrossRef]

4. World Health Organisation. World Malaria Report 2024. Geneva, Switzerland:World Health Organisation;2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2024 [Last accessed on 2025 Jun 13].

5. Franklinos LH, Jones KE, Redding DW, Abubakar I. The effect of global change on mosquito-borne disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(9):302-12. [CrossRef]

6. Sultana N, Raul PK, Goswami D, Das D, Islam S, Tyagi V, et al. Bio-nanoparticle assembly:A potent on-site biolarvicidal agent against mosquito vectors. RSC Adv. 2020;10(16):9356-68.[CrossRef]

7. Yadav M, Dahiya N, Sehrawat N. Mosquito gene targeted RNAi studies for vector control. Funct Integr Genomics. 2023;23(2):180.[CrossRef]

8. Airs P, Bartholomay L. RNA interference for mosquito and mosquito-borne disease control. Insects. 2017;8(1):4.[CrossRef]

9. Benelli G, Jeffries CL, Walker T. Biological control of mosquito vectors:Past, present, and future. Insects. 2016;7(4):52.[CrossRef]

10. Alphey L, Beard CB, Billingsley P, Coetzee M, Crisanti A, Curtis C, et al. Malaria control with genetically manipulated insect vectors. Science. 2002;298(5591):119-21.[CrossRef]

11. Eckhoff PA, Wenger EA, Godfray HC, Burt A. Impact of mosquito gene drive on malaria elimination in a computational model with explicit spatial and temporal dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(2):E255-E264. [CrossRef]

12. Gantz VM, Jasinskiene N, Tatarenkova O, Fazekas A, Macias VM, Bier E, et al. Highly efficient Cas9-mediated gene drive for population modification of the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles stephensi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(49):E6736-43.[CrossRef]

13. Ricci I, Valzano M, Ulissi U, Epis S, Cappelli A, Favia G. Symbiotic control of mosquito borne disease. Pathog Glob Health. 2012;106(7):380-5.[CrossRef]

14. Wilke ABB, Marrelli MT. Paratransgenesis:A promising new strategy for mosquito vector control. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8(1):342.[CrossRef]

15. Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998 Feb;391(6669):806-11.[CrossRef]

16. Reis RS. The entangled history of animal and plant microRNAs. Funct Integr Genomics. 2017;17(2-3):127-34.[CrossRef]

17. Azimzadeh Jamalkandi S, Azadian E, Masoudi-Nejad A. Human RNAi pathway:Crosstalk with organelles and cells. Funct Integr Genomics. 2014;14(1):31-46.[CrossRef]

18. Balakrishna Pillai A, Nagarajan U, Mitra A, Krishnan U, Rajendran S, Hoti SL, et al. RNA interference in mosquito:Understanding immune responses, double-stranded RNA delivery systems and potential applications in vector control. Insect Mol Biol. 2017;26(2):127-39.[CrossRef]

19. Hapairai LK, Mysore K, Sun L, Li P, Wang CW, Scheel ND, et al. Characterization of an adulticidal and larvicidal interfering RNA pesticide that targets a conserved sequence in mosquito G protein-coupled dopamine 1 receptor genes. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2020;120:103359.[CrossRef]

20. Mysore K, Hapairai L, Sun L, Li P, Wang C, Scheel N, et al. Characterization of a dual-action adulticidal and larvicidal interfering RNA pesticide targeting the Shaker gene of multiple disease vector mosquitoes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(7):0008479.[CrossRef]

21. Wiltshire RM, Duman-Scheel M. Advances in oral RNAi for disease vector mosquito research and control. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2020;40:18-23.[CrossRef]

22. Zhang J, Khan SA, Heckel DG, Bock R. Next-generation insect-resistant plants:RNAi-mediated crop protection. Trends Biotechnol. 2017;35(9):871-82.[CrossRef]

23. Li M, Yan C, Jiao Y, Xu Y, Bai C, Miao R, et al. Site-directed RNA editing by harnessing ADARs:Advances and challenges. Funct Integr Genomics. 2022;22(6):1089-103.[CrossRef]

24. Munawar K, Alahmed AM, Khalil SM. Delivery methods for RNAi in mosquito larvae. J Insect Sci. 2020;20(4):12.[CrossRef]

25. Mysore K, Sun L, Hapairai L, Wang C, Roethele J, Igiede J, et al. A broad-based mosquito yeast interfering RNA pesticide targeting rbfox1 represses notch signaling and kills both larvae and adult mosquitoes. Pathogens. 2021;10(10):1251.[CrossRef]

26. Mysore K, Li P, Wang CW, Hapairai LK, Scheel ND, Realey JS, et al. Characterization of a broad-based mosquito yeast interfering RNA larvicide with a conserved target site in mosquito semaphorin-1a genes. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12(1):256.[CrossRef]

27. Dittmer J, Alafndi A, Gabrieli P. Fat body-specific vitellogenin expression regulates host-seeking behaviour in the mosquito Aedes albopictus. PLoS Biology. 2019;17(5):3000238.[CrossRef]

28. Maharaj S, Ekoka E, Erlank E, Nardini L, Reader J, Birkholtz LM, et al. The ecdysone receptor regulates several key physiological factors in Anopheles funestus. Malar J. 2022;21(1):97.[CrossRef]

29. Taracena ML, Hunt CM, Benedict MQ, Pennington PM, Dotson EM. Downregulation of female doublesex expression by oral-mediated RNA interference reduces number and fitness of Anopheles gambiae adult females. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12(1):170.[CrossRef]

30. Huang X, Kaufman P, Athrey G, Fredregill C, Alvarez C, Shetty V, et al. Potential key genes involved in metabolic resistance to malathion in the southern house mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus, and functional validation of CYP325BC1 and CYP9M12 as candidate genes using RNA interference. BMC Genomics. 2023;24(1):160.[CrossRef]

31. Ingham VA, Pignatelli P, Moore JD, Wagstaff S, Ranson H. The transcription factor Maf-S regulates metabolic resistance to insecticides in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. BMC Genomics. 2017;18(1):669.[CrossRef]

32. Li X, Hu S, Yin H, Zhang H, Zhou D, Sun Y, et al. MiR-4448 is involved in deltamethrin resistance by targeting CYP4H31 in Culex pipiens pallens. Parasit Vectors. 2021 Mar 16;14(1):159.[CrossRef]

33. Lopez SB, Guimarães-Ribeiro V, Rodriguez JV, Dorand FA, Salles TS, Sá-Guimarães TE, et al. RNAi-based bioinsecticide for Aedes mosquito control. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):4038.[CrossRef]

34. Zhang C, Ding Y, Zhou M, Tang Y, Chen R, Chen Y, et al. RNAi-mediated CHS-2 silencing affects the synthesis of chitin and the formation of the peritrophic membrane in the midgut of Aedes albopictus larvae. Parasit Vectors. 2023;16(1):259.[CrossRef]

35. Debalke S, Habtewold T, Duchateau L, Christophides GK. The effect of silencing immunity related genes on longevity in a naturally occurring Anopheles arabiensis mosquito population from southwest Ethiopia. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12(1):174.[CrossRef]

36. Dong Y, Dong S, Dizaji NB, Rutkowski N, Pohlenz T, Myles K, et al. The Aedes aegypti siRNA pathway mediates broad-spectrum defense against human pathogenic viruses and modulates antibacterial and antifungal defenses. PLoS Biol. 2022;20(6):3001668.[CrossRef]

37. Prates L, Fiebig J, Schlosser H, Liapi E, Rehling T, Lutrat C, et al. Challenges of robust RNAi-mediated Gene silencing in Aedes Mosquitoes. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(10):5218.[CrossRef]

38. Fei X, Zhang Y, Ding L, Xiao S, Xie X, Li Y, et al. Development of an RNAi-based microalgal larvicide for the control of Aedes aegypti. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14(1):387.[CrossRef]

39. Negri A, Ferrari M, Nodari R, Coppa E, Mastrantonio V, Zanzani S, et al. Gene silencing through RNAi and antisense Vivo-Morpholino increases the efficacy of pyrethroids on larvae of Anopheles stephensi. Malar J. 2019;18(1):294.[CrossRef]

40. Arshad F, Sharma A, Lu C, Gulia-Nuss M. RNAi by soaking Aedes aegyptipupae in dsRNA. Insects. 2021;12(7):634.[CrossRef]

41. Williams A, Sanchez-Vargas I, Reid W, Lin J, Franz A, Olson K. The antiviral small-interfering RNA pathway induces Zika Virus resistance in transgenic Aedes aegypti. Viruses. 2020;12(11):1231.[CrossRef]

42. Mysore K, Hapairai LK, Wei N, Realey JS, Scheel ND, Severson DW, et al. Preparation and use of a yeast shRNA delivery system for gene silencing in mosquito larvae. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1858:213-31.[CrossRef]

43. Adedeji EO, Beder T, Damiani C, Cappelli A, Accoti A, Tapanelli S, et al. Combination of computational techniques and RNAi reveal targets in Anopheles gambiae for malaria vector control. PLoS One. 2024;19(7):0305207. [CrossRef]

44. Letini?BD, Dahan-Moss Y, Koekemoer LL. Characterising the effect of Akirin knockdown on Anopheles arabiensis (Diptera:Culicidae) reproduction and survival, using RNA-mediated interference. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):022?. [CrossRef]

45. Bui M, Dalla Benetta E, Dong Y, Zhao Y, Yang T, Li M, et al. CRISPR mediated transactivation in the human disease vector Aedes aegypti. PLoS Pathog. 2023;19(1):1010842.[CrossRef]

46. Lu YH, Liu Y, Lin YC, Su YJ, Henry D, Lacarriere V, et al. Lipoplex-based RNA delivery system enhances RNAi efficiency for targeted Pest control in Spodoptera litura. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;319:145091.[CrossRef]

47. Mohammed M, Syeda J, Wasan K, Wasan E. An overview of chitosan nanoparticles and its application in non-parenteral drug delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2017;9(4):53.[CrossRef]

48. Jeon SJ, Oh M, Yeo WS, Galvão KN, Jeong KC. Underlying mechanism of antimicrobial activity of chitosan microparticles and implications for the treatment of infectious diseases. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):92723.[CrossRef]

49. Zhang X, Zhang J, Zhu KY. Chitosan/double?stranded RNA nanoparticle?mediated RNA interference to silence chitin synthase genes through larval feeding in the African malaria mosquito (Anopheles gambiae). Insect Mol Biol. 2010;19(5):683-93.[CrossRef]

50. Dhandapani RK, Gurusamy D, Howell JL, Palli SR. Development of CS-TPP-dsRNA nanoparticles to enhance RNAi efficiency in the yellow fever mosquito. Aedes aegypti. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):8775.[CrossRef]

51. Das S, Debnath N, Cui Y, Unrine J, Palli SR. Chitosan, carbon quantum dot, and silica nanoparticle mediated dsRNA delivery for gene silencing in Aedes aegypti:A comparative analysis. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7(35):19530-5.[CrossRef]

52. Cancino-Rodezno A, Lozano L, Oppert C, Castro JI, Lanz-Mendoza H, Encarnación S, et al. Comparative proteomic analysis of Aedes aegypti larval midgut after intoxication with Cry11Aa toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):37034.[CrossRef]

53. Guan R, Chu D, Han X, Miao X, Li H. Advances in the development of microbial double-stranded RNA production systems for application of RNA interference in agricultural pest control. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021;9:753790.[CrossRef]

54. Whitten MMA, Facey PD, Del Sol R, Fernández-Martínez LT, Evans MC, Mitchell JJ, et al. Symbiont-mediated RNA interference in insects. Proc R Soc B. 2016;283(1825):20160042.[CrossRef]

55. Sen P. RNAi and CRISPR:Promising tool for gene silencing. Biomed J Sci Technical Res. 2021;40(3):32210-5.[CrossRef]

56. Lu Y, Deng X, Zhu Q, Wu D, Zhong J, Wen L, et al. The dsRNA delivery, Targeting and application in pest control. Agronomy. 2023;13(3):714.[CrossRef]

57. Zhou P, Bibek GC, Stolte F, Wu C. Use of CRISPR interference for efficient and rapid gene inactivation in Fusobacterium nucleatum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2024;90(2):01665-23.[CrossRef]

58. Kornienko IV, Aramova OY, Tishchenko AA, Rudoy DV, Chikindas ML. RNA stability:A review of the role of structural features and environmental conditions. Molecules. 2024;29(24):5978.[CrossRef]

59. Mathur S, Chaturvedi A, Ranjan R. Advances in RNAi-based nanoformulations:Revolutionizing crop protection and stress tolerance in agriculture. Nanoscale Adv. 2025;7(7):1768-83.[CrossRef]

60. Adedeji EO, Ogunlana OO, Fatumo S, Aromolaran OT, Beder T, Koenig R, et al. The Central Metabolism Model of Anopheles gambiae:A Tool for Understanding Malaria Vector Biology. Biotechnological Approaches to Sustainable Development Goals. 2023;229-8.. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-031-33370-5_16 [Last accessed on 2025 Jul 01].[CrossRef]