1. INTRODUCTION

Probiotics are defined as live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer health benefits to the host by modulating the gut microbiota, enhancing immune responses, and inhibiting the colonization of pathogenic bacteria [1-3]. The increasing global interest in functional foods and natural therapeutics has accelerated the search for novel probiotic strains with superior gastrointestinal resilience, colonization potential, and bioactive functionalities [4-6]. Although many commercial probiotics are derived from conventional dairy or fermented sources, there is a growing scientific imperative to explore alternative, underutilized niches for discovering robust and safe strains. Milk and dairy products serve as ideal substrates for the growth of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) due to their rich nutrient composition [7]. In particular, goat milk, an important commodity from small ruminants, has gained prominence for its excellent digestibility, lower allergenicity, and unique nutritional attributes, including bioactive peptides, oligosaccharides, and medium-chain fatty acids [8]. Distinct from cow milk, goat milk supports a diverse microbial community with significant probiotic potential [9-11]. These microbial populations may contribute not only to human health but also to gut health and disease resistance in small ruminants themselves, especially when integrated into feed-based functional interventions.

Despite its favorable characteristics, raw goat milk remains underexplored as a natural reservoir for probiotic discovery. Systematic characterization of its microbiota is essential for identifying strains capable of tolerating gastrointestinal stress, exhibiting antimicrobial activity, and modulating host immunity. The application of integrated phenotypic, biochemical, and molecular techniques, particularly 16S rRNA gene sequencing, facilitates accurate taxonomic identification and functional assessment of such strains [12]. This study aims to isolate, functionally characterize, and molecularly identify probiotic bacteria from raw goat milk collected from traditional small ruminant farming systems. Each isolate was assessed for critical probiotic traits, including acid and bile salt tolerance, antimicrobial efficacy, auto-aggregation, and adhesion to intestinal epithelial cells, followed by genotypic identification. The overarching goal is to identify novel goat-derived probiotic candidates with potential applications in enhancing gut health, developing functional foods, and formulating feed additives for improved small ruminant health and productivity, while also extending their relevance to human health applications. These findings aim to broaden the understanding of goat milk microbiota and support the development of sustainable probiotic strategies in both veterinary and human health domains. While previous studies have characterized probiotic strains from goat milk, the majority have primarily focused on conventional Lactobacillus species and a limited set of functional attributes [13,14]. However, a considerable knowledge gap remains in the isolation and functional assessment of diverse bacterial taxa, particularly from traditional smallholder goat-rearing systems that sustain unique microbial communities [15]. In this study, we address this gap by systematically isolating and functionally characterizing a broader spectrum of probiotic candidates, including less-studied species such as Heyndrickxia coagulans and Bacillus aerolacticus. Using an extensive suite of in vitro assays, including acid and bile tolerance, epithelial adhesion, antimicrobial activity, and technological properties, we provide a comprehensive evaluation of their probiotic potential. This work offers novel insights into goat milk as an underexplored reservoir of functional microbes and significantly expands the repertoire of candidate probiotics with prospective applications in both animal health management and human functional food development.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Sample Collection

Raw goat milk samples (n = 20) were aseptically collected from smallholder farms in the Tirupati region of Andhra Pradesh, India. Samples were transported under refrigerated conditions (4°C) and processed within 24 h to preserve microbial viability and prevent compositional alterations.

2.2. Isolation of LAB

One milliliter of each raw milk sample was serially diluted in sterile 0.85% (w/v) sodium chloride solution to obtain dilutions up to 10−8. Aliquots from each dilution were spread-plated onto de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) agar (HiMedia, India) supplemented with 0.01% (v/v) cycloheximide to inhibit fungal growth. Plates were incubated anaerobically at 37°C for 72–96 h. Colonies exhibiting distinct morphologies were presumptively identified as LAB and purified by repeated sub-culturing on MRS agar. Purified isolates were maintained in MRS broth supplemented with 30% (v/v) glycerol and stored at −20°C for further characterization.

2.3. Phenotypic Identification

Gram staining was performed to select Gram-positive isolates, which were subsequently subjected to a series of biochemical assays, including KOH solubility, catalase, oxidase, IMViC (Indole, Methyl Red, Voges–Proskauer, Citrate), and nitrate reduction tests. The KOH test was used to confirm Gram positivity, indicated by the absence of viscous thread formation. Catalase activity was evaluated using 3% hydrogen peroxide, and oxidase activity was determined using oxidase reagent strips. IMViC tests were conducted according to standard microbiological protocols described by Cappuccino and Sherman [16]. Nitrate reduction was assessed by adding sulfanilic acid and α-naphthylamine; a red color indicated a positive result.

2.4. Identification at the Species Level

2.4.1. Salt and pH tolerance

Salt tolerance was evaluated by culturing the isolates in MRS broth containing 2%, 4%, and 6.5% NaCl at 37°C. pH tolerance was assessed by incubating isolates in MRS broth adjusted to pH values of 2.0, 4.2, 4.4, 8.5, and 9.6. Growth was monitored after 24 h of incubation based on turbidity.

2.4.2. Sugar fermentation profile

The carbohydrate fermentation profile was determined using phenol red broth containing 1% (w/v) of 22 different carbohydrates (Loba Chemie, India). A color change from red to yellow indicated acid production, and gas formation in Durham tubes confirmed fermentative metabolism.

2.5. Molecular Identification

2.5.1. Genomic DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from the LAB isolates using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide method. Briefly, bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min and lysed. The lysate was subjected to chloroform/isoamyl alcohol extraction, and the DNA was precipitated with isopropanol. The resulting DNA pellet was washed, dried, and purified using silica-based spin columns for further molecular analysis.

2.5.2. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification

The 16S rRNA gene was amplified using universal primers and DreamTaq Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific). The thermocycling conditions included an initial denaturation at 95°C, annealing at 50°C, extension at 72°C, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Amplified products were confirmed by electrophoresis on a 1.2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide.

2.6. Probiotic Characterization

2.6.1. Bile salt tolerance

Bile salt tolerance was evaluated by culturing isolates in MRS broth supplemented with 0.3% (w/v) oxgall bile salts. Optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was measured after 3 h of incubation to assess growth.

2.6.2. Adhesion to intestinal cells

The adhesion ability of bacterial isolates was evaluated using the human intestinal epithelial cell line Caco-2, following established protocols with minor modifications [17,18]. Confluent Caco-2 monolayers were cultured in 24-well plates, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and inoculated with bacterial suspensions (108 Colony Forming Unit (CFU)/mL). After incubation at 37°C for 1 h under 5% CO2, non-adherent bacteria were removed by three PBS washes. The cells were then lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100, and adhered bacteria were quantified by serial dilution plating on MRS agar. To improve accuracy, adhesion efficiency was calculated by correlating absorbance at 595 nm (OD595) with CFU counts using a standard calibration curve (R² = 0.95). A representative calibration plot was included to validate this correlation. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (ATCC 53103), a well-characterized probiotic with high adhesion capacity, was used as a positive control.

2.6.3. Aggregation assays

Autoaggregation ability was assessed by measuring the decrease in OD600 over a 24-h period. For coaggregation, equal volumes of LAB and indicator bacterial suspensions were mixed, and OD600 was recorded at 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min to evaluate interaction dynamics.

2.6.4. Antibacterial activity

The antimicrobial activity of probiotic culture supernatants was evaluated using the agar well diffusion method. Sterile nutrient agar plates were prepared, autoclaved at 121°C for 15 min, and poured into petri dishes. After solidification, 6 mm wells were aseptically punched and filled with 50 μL of sterile, cell-free culture supernatant. Plates were incubated at 37°C overnight, and inhibition zones around the wells were measured. Antibacterial activity was tested against Escherichia coli (ATCC 9837), Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 6538), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 9027), and Klebsiella pneumoniae (ATCC 700603). Streptomycin served as the positive control.

2.7. Technological Properties

2.7.1. Proteolytic activity

LAB isolates were spot-inoculated onto skim milk agar (1% w/v skim milk) and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Proteolytic activity was indicated by the formation of clear halos ≥2 mm in diameter around the colonies.

2.7.2. Lipolytic activity

Lipase production was assessed by culturing the isolates on tributyrin agar at 30°C for 5 days. The presence of clear zones surrounding colonies indicated lipolytic activity.

2.7.3. Diacetyl production

Diacetyl production was determined by inoculating sterile skim milk with LAB isolates and incubating at 30°C for 24 h. Following incubation, α-naphthol and KOH were added, and the development of a red ring indicated the presence of diacetyl.

2.7.4. Exopolysaccharide (EPS) production

Bacterial isolates were cultured in MRS broth supplemented with 5% glucose at 37°C for 72 h. EPS production was quantified using the phenol–sulfuric acid method described by Dubois et al. [19]. Cell-free culture supernatants were mixed with phenol and concentrated sulfuric acid, and absorbance was measured at 490 nm. Carbohydrate concentration was calculated from a standard curve and used to estimate EPS yield.

2.8. Safety Assessment

2.8.1. Biogenic amine production

Biogenic amine production was tested using decarboxylase agar supplemented with tyrosine, histidine, and ornithine. A color change from yellow to purple indicated the production of respective amines.

2.8.2. Hemolytic activity

Hemolysis was evaluated by streaking isolates onto brain–heart infusion (BHI) agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood and incubating at 30°C for 72 h. The absence of clear zones indicated non-hemolytic behavior.

2.8.3. Gelatinase activity

Gelatinase activity was assessed by inoculating isolates into nutrient gelatin tubes and incubating at 30°C for 14 days. Gelatin hydrolysis was evaluated following the method of Cruickshank et al. [20]. After incubation, tubes were chilled, and liquefaction of gelatin was interpreted as a positive result. In parallel, plates were flooded with ammonium sulfate solution, where the appearance of clear zones around colonies indicated gelatinase activity.

2.8.4. Coagulase test

For coagulase activity, isolates were mixed with rabbit plasma and incubated at 30°C for 6 h. The appearance of clotted clumps confirmed coagulase production.

2.9. Fermented Milk Production

Selected LAB strains were inoculated (2% v/v) into autoclaved skim milk and incubated at 37°C for 5 h to produce fermented milk. Samples were stored at 4°C for up to 21 days. Viability and pH were monitored at weekly intervals.

2.10. Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis

PCR products were purified and sequenced commercially using the Sanger method (ABI 3730XL sequencer). Obtained sequences were analyzed using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) tool against the NCBI GenBank database to identify the closest homologs. Multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic tree construction was performed using MEGA 11 software. A Neighbor-Joining tree was generated with 1,000 bootstrap replications to determine the evolutionary relationships of the isolates with reference strains.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3), and results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for pairwise comparisons. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism version 9.0.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Isolation and Preliminary Screening of Bacterial Strains

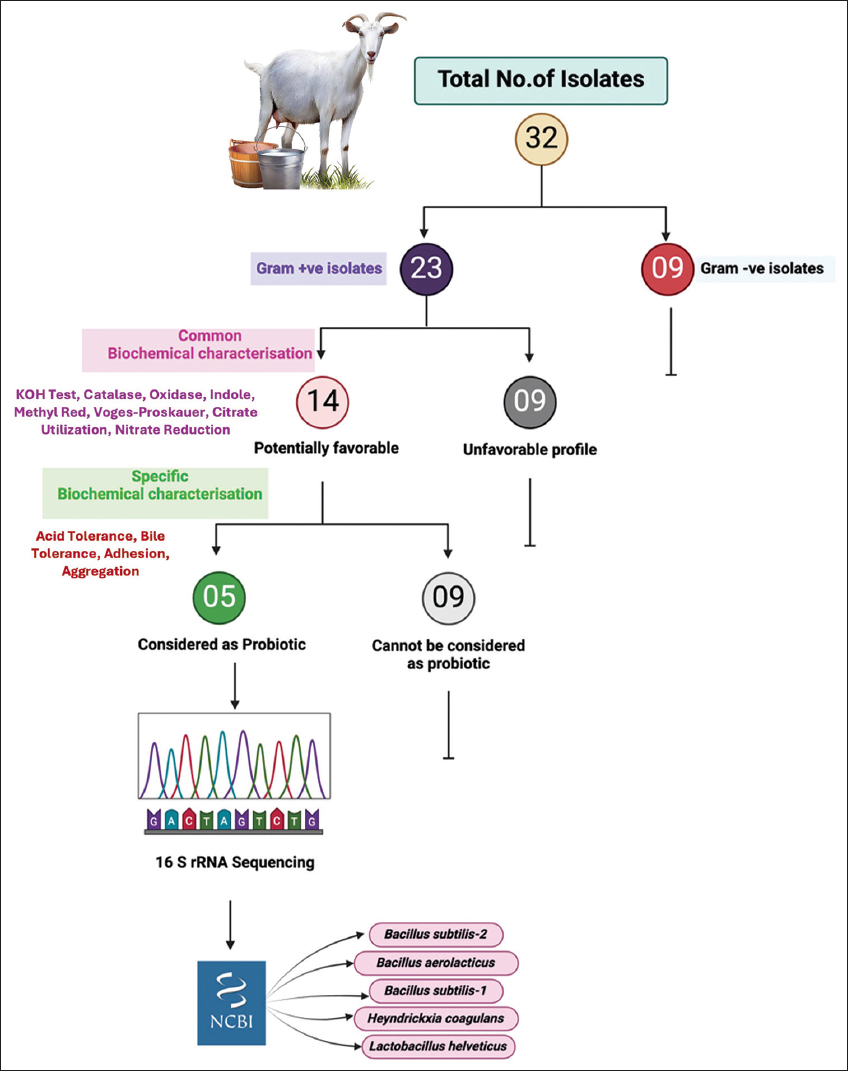

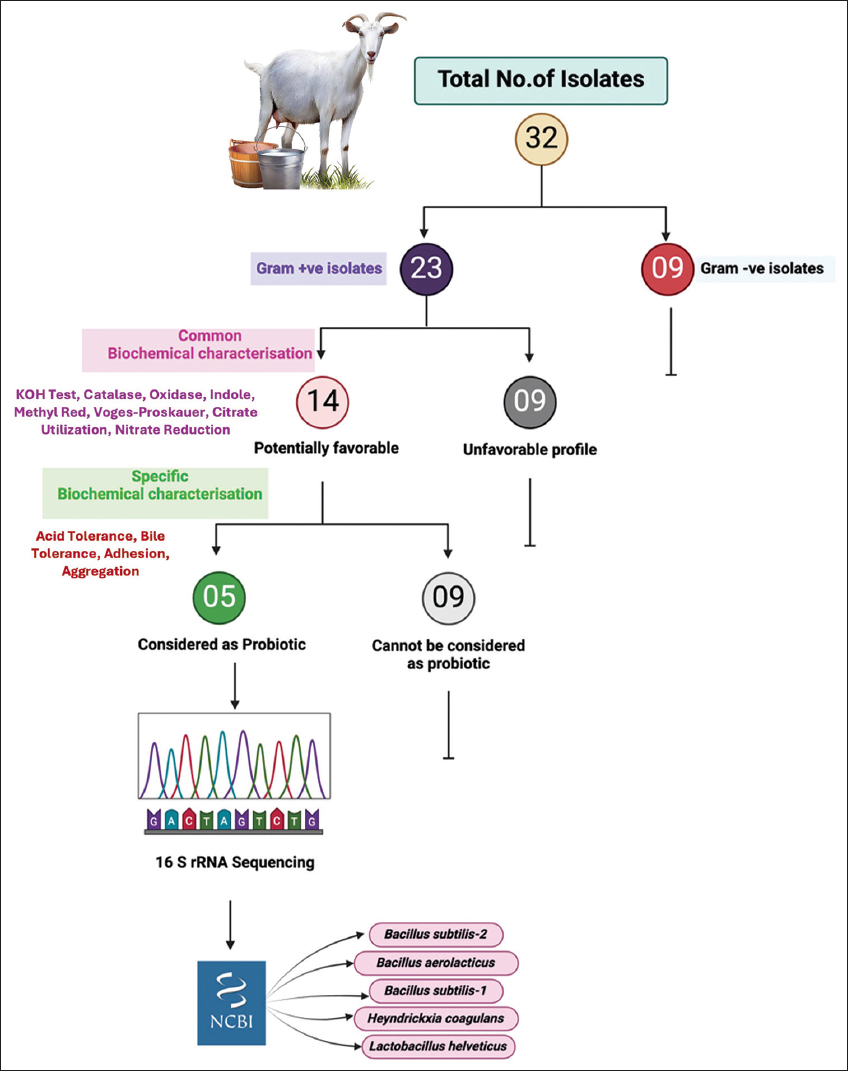

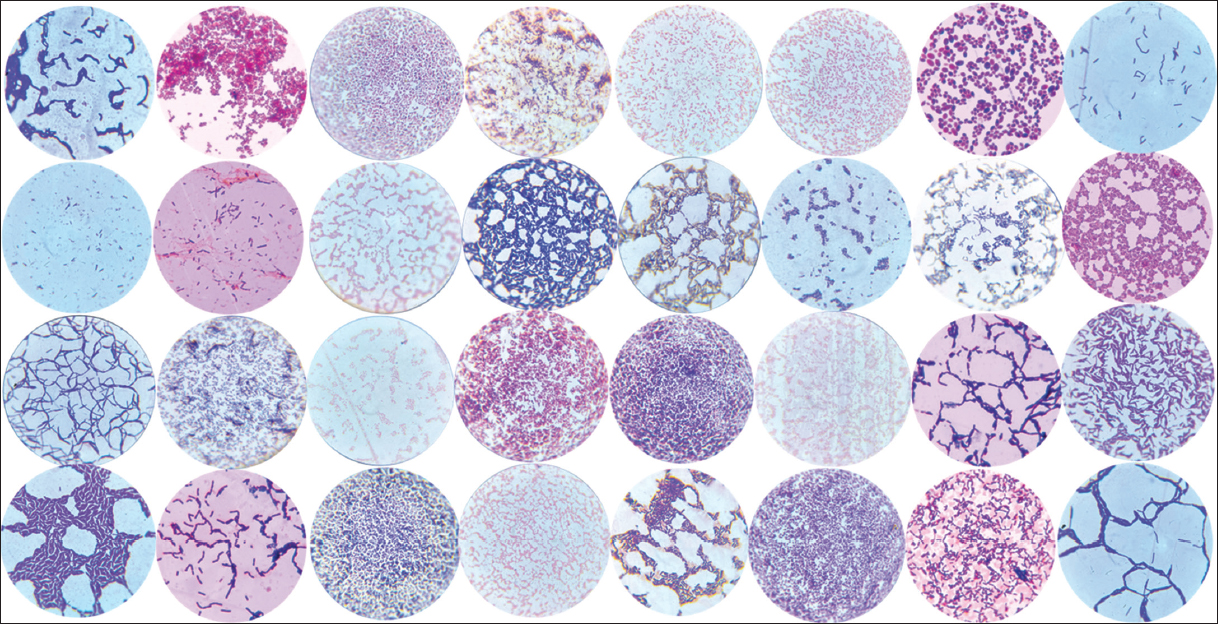

A total of 32 morphologically distinct bacterial isolates were recovered from raw goat milk samples [Figure 1], a rich ecological niche for probiotic candidates due to its diverse microbiota and bioactive components. Initial Gram staining and KOH string test distinguished 23 Gram-positive rod-shaped isolates suitable for further evaluation, while nine Gram-negative strains were excluded [Figure 2]. This selection criterion is congruent with probiotic development paradigms, which emphasize Gram-positive spore-forming or lactic acid-producing bacteria owing to their resilience under gastrointestinal conditions and established generally recognized as safe (GRAS) status in food applications.

| Figure 1: Selection and identification of probiotic strains isolated from raw goat milk. A total of 32 bacterial isolates were obtained, including 23 Gram-positive and 9 Gram-negative isolates. Common biochemical characterization identified 14 potentially favorable Gram-positive isolates, of which 5 were confirmed as probiotics based on specific biochemical characterization. These strains underwent 16S rRNA sequencing and were identified as Bacillus subtilis (two strains), Lactobacillus helveticus, Bacillus aerolacticus, and Heyndrickxia coagulans. The remaining 9 isolates did not meet probiotic criteria.

[Click here to view] |

| Figure 2: Gram’s staining of the isolates, confirming the presence of Gram-positive rod-shaped bacteria.

[Click here to view] |

3.2. Biochemical Profiling of Isolates

Biochemical analyses provided a preliminary functional characterization of the isolates [Table 1]. Catalase activity, observed in 16 isolates, reflects the oxidative stress tolerance critical for survival during industrial processing and intestinal colonization. The low frequency of oxidase-positive isolates (n = 2) is consistent with the facultatively anaerobic nature of most probiotic bacteria. IMViC profiles and nitrate reduction capabilities further delineated functional diversity, facilitating the selection of 14 metabolically versatile strains. These biochemical traits are relevant not only for species-level identification but also for predicting potential metabolic interactions with host and dietary components in vivo.

Table 1: Selection of 14 strains based on common biochemical characterizations, including catalase, oxidase, and sugar fermentation tests. Each experiment was performed in triplicate (n=3).

| Isolate ID | KOH test | Catalase | Oxidase | Indole | Methyl red | Voges-Proskauer | Citrate utilization | Nitrate reduction |

|---|

| 1 | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| 2 | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| 3 | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + |

| 4 | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| 5 | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| 6 | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| 7 | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + |

| 8 | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| 9 | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| 10 | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | + |

| 11 | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | − |

| 12 | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| 13 | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| 14 | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | − |

| 15 | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 16 | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| 17 | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| 18 | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| 19 | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| 20 | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| 21 | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | + |

| 22 | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + |

| 23 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

3.3. In Vitro Evaluation of Probiotic Functional Attributes

Fourteen bacterial isolates were subjected to a comprehensive in vitro assessment to characterize key probiotic properties [Table 2]. Acid tolerance, evaluated at pH 3.0 to simulate gastric conditions, revealed survival rates ranging from 62% to 90%. Isolates demonstrating viability below 50% were excluded due to insufficient acid resilience. Bile salt tolerance, assessed in the presence of 0.3% (w/v) oxgall, ranged from 58% to 85%. These two parameters are critical for predicting gastrointestinal transit survival, a prerequisite for exerting probiotic effects in vivo [21]. Adhesion to Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells was measured as a proxy for colonization capacity and mucosal interaction [22]. Twelve isolates exhibited high adhesion efficiency (>60%), indicative of potential for epithelial persistence, immune modulation, and competitive exclusion of pathogens. Autoaggregation ability, which facilitates biofilm formation and intercellular communication, exceeded 70% in eight isolates. Coaggregation with enteric pathogens such as E. coli and S. aureus surpassed 70% in multiple strains, underscoring their ecological competitiveness and potential to inhibit pathogen colonization through coaggregation-mediated interference.

Table 2: Selection of 5 potent probiotic strains based on specific biochemical characterizations, such as bile salt tolerance, acid resistance, and enzymatic activity. Each experiment was performed in triplicate (n=3).

| Isolate ID | Acid tolerance | Bile tolerance | Adhesion | Aggregation |

|---|

| 1 | + | + | + | + |

| 2 | + | + | + | + |

| 3 | + | + | + | − |

| 4 | − | + | + | + |

| 5 | + | − | − | − |

| 6 | + | + | + | + |

| 7 | − | + | + | + |

| 8 | − | − | − | − |

| 9 | + | + | + | − |

| 10 | + | + | + | − |

| 11 | + | + | − | + |

| 12 | + | + | + | − |

| 13 | − | − | − | − |

| 14 | + | − | + | + |

| 15 | − | − | − | − |

| 16 | + | + | − | + |

| 17 | + | + | − | − |

| 18 | + | + | + | + |

| 19 | + | + | + | + |

| 20 | + | + | − | − |

| 21 | + | − | + | − |

| 22 | − | − | + | + |

| 23 | − | − | − | − |

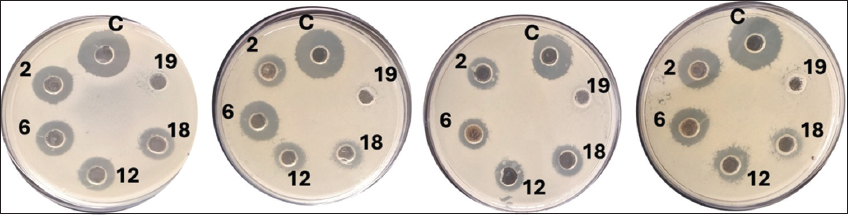

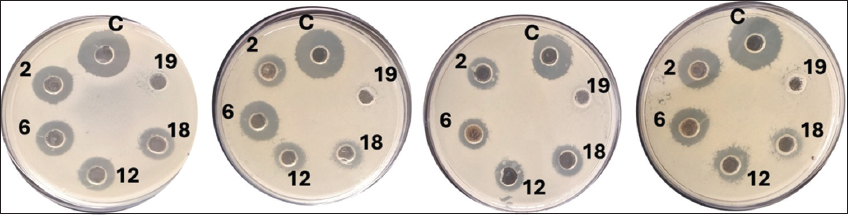

Antimicrobial activity was evaluated using agar well diffusion assays against four clinically significant pathogens: E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and K. pneumoniae [Figure 3 and Table 3]. All tested isolates, with the exception of isolate 19, exhibited broad-spectrum antagonistic activity, as evidenced by the formation of clear inhibition zones, indicative of potent inhibitory effects against the tested pathogens. The observed antimicrobial effects are presumably mediated by the secretion of organic acids, bacteriocins, hydrogen peroxide, or other antimicrobial compounds [23]. While isolate 19 (H. coagulans) did not show detectable antimicrobial activity in our assays, it displayed positive results in multiple other probiotic functional tests, including robust acid and bile salt tolerance, high adhesion efficiency to intestinal cells, and notable enzymatic activities. These favorable functional traits warranted further molecular characterization and highlight the multifaceted nature of probiotic potential beyond antimicrobial effects alone. Variability in pathogen susceptibility, particularly between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, may be attributed to differences in cell wall architecture and intrinsic resistance mechanisms [24]. Based on cumulative in vitro performance, including high acid and bile tolerance (85–90% and 78–85%, respectively), strong epithelial adhesion (>65%), substantial autoaggregation (>80%) and coaggregation (>70%), and consistent antimicrobial activity, five top-performing strains were selected for molecular identification and subsequent functional characterization.

| Figure 3: Antibacterial activity of bacterial isolates, through the agar well-diffusion method against Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus pathogens. The zones marked with the letter C indicate the control (streptomycin), while the numbers 2, 6, 12, 18, and 19 represent the isolated ID numbers. The variation in inhibition zone sizes reflects differences in the potency of the isolates against the test pathogens. Each experiment was performed in triplicate (n = 3).

[Click here to view] |

Table 3: Antibacterial activity of bacterial isolates assessed by the agar well-diffusion method against pathogenic strains of Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus. The measurements are represented as mean±standard deviation (in mm) from triplicate assays (n=3).

| Test organism | Zone of inhibition in mm |

|---|

|

|---|

| Isolate-2 | Isolate-6 | Isolate-12 | Isolate-18 | Isolate-19 | Control |

|---|

| Escherichia coli | 10.1 ± 0.2 | 13.4 ± 0.3 | 10.5 ± 0.3 | 9.2 ± 0.2 | − | 16.0 ± 0.4 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 8.5 ± 0.2 | 12.6 ± 0.3 | 9.5 ± 0.2 | 7.5 ± 0.3 | − | 15.3 ± 0.3 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 8.0 ± 0.2 | 9.9 ± 0.4 | 9.8 ± 0.3 | 8.5 ± 0.3 | − | 14.2 ± 0.3 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 10.3 ± 0.2 | 12.4 ± 0.4 | 10.2 ± 0.2 | 8.3 ± 0.2 | − | 16.5 ± 0.3 |

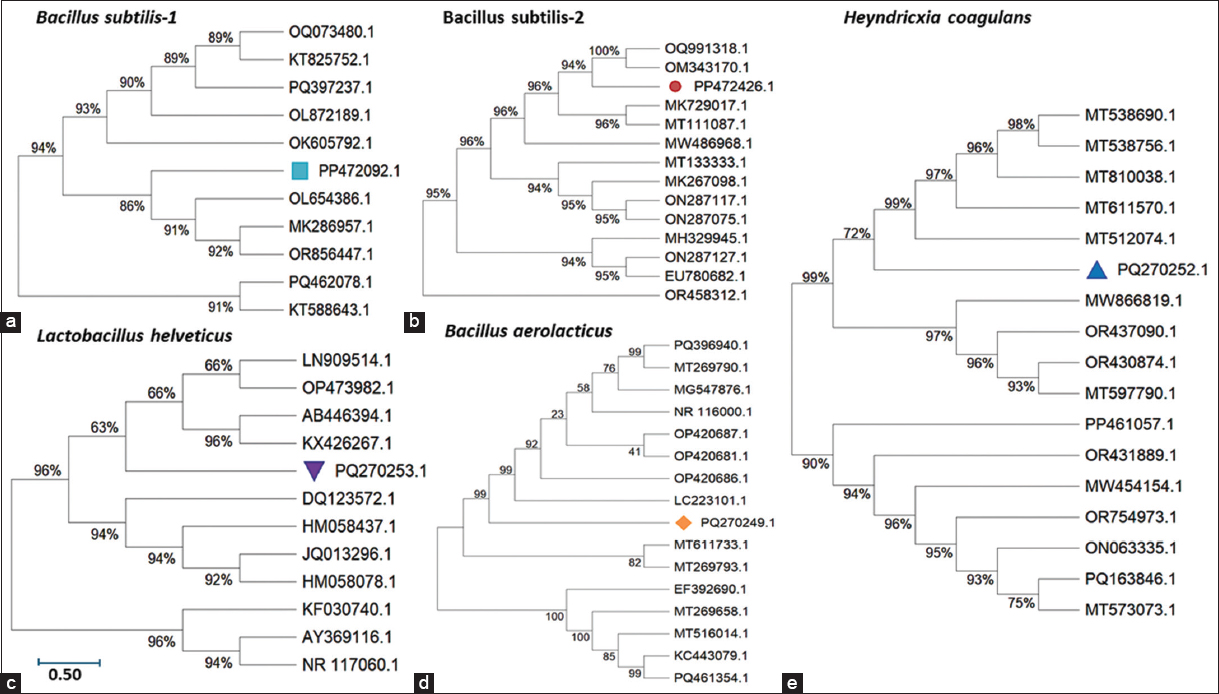

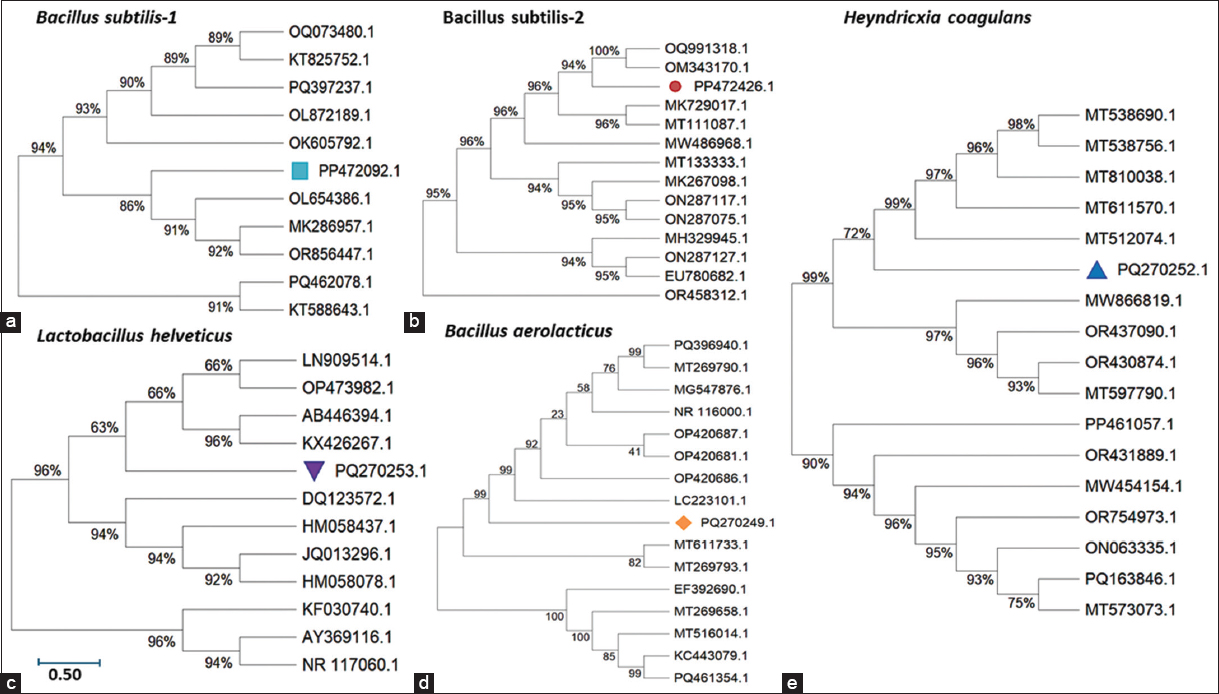

3.4. Molecular Identification and Phylogenetic Affiliation

16S rRNA gene sequencing identified the selected strains as Lactobacillus helveticus, H. coagulans, B. aerolacticus, and two distinct isolates of Bacillus subtilis [Table 4]. These identifications were confirmed through sequence alignment and BLAST homology against the NCBI GenBank database, and accession numbers were duly obtained. The inclusion of L. helveticus and B. subtilis aligns with prior reports emphasizing their robust gastrointestinal survivability, immunomodulatory potential, and industrial adaptability. H. coagulans is a notable spore-forming probiotic with emerging relevance in functional foods and pharmaceutical formulations, attributed to its acid-stable spores and consistent viability under diverse environmental conditions. The presence of B. aerolacticus, although less commonly reported, expands the spectrum of potential probiotic diversity derived from dairy niches and warrants further functional and genomic characterization. These molecular findings reinforce the phenotypic assessments and affirm the suitability of these isolates for future application in fermented dairy products, symbiotic formulations, or next-generation probiotic delivery systems.

Table 4: Technological properties of dominant lactic acid bacteria isolated from raw goat milk. Each experiment was performed in triplicate (n=3).

| Strains | Proteolytic activity | Lipolytic activity | Diacetyl production | Exopolysaccharide production (mg/L) |

|---|

| Bacillus subtilis (Strain 1) | + | + | + | 85.0±2.0c |

| Bacillus subtilis (Strain 2) | + | + | + | 20.2±1.7h |

| Lactobacillus helveticus | +a | +wb | + | 58.0±2.6e |

| Bacillus aerolacticus | + | +w | + | 22.3±2.5gh |

| Heyndrickxia coagulans | + | +w | + | 93.0±1.1a |

| P-value | 0.000 | − | − | − |

a: Signs indicated as ‘+’ = positive halo formation in the colony; ‘−’ = no halo formed in the colony. b: +w: Low halo formation in the colony. c: The signs indicated red ring formation. d: Exopolysaccharide means with different superscripts are significantly different (P<0.05) Values in the Exopolysaccharide production column followed by different superscript letters (a–h) are significantly different (p < 0.05) according to post-hoc analysis.

3.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

To establish the taxonomic identities and evolutionary relationships of the five potent isolates, 16S rRNA gene sequencing was conducted, followed by phylogenetic tree construction using the Neighbor-Joining method with MEGA software. Bootstrap validation (1,000 replicates) confirmed the robustness of tree topology [Figure 4]. The 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis confirmed that the isolated probiotic strains belong to distinct phylogenetic clades, encompassing well-characterized species such as L. helveticus and B. subtilis (two strains), as well as less commonly reported species like H. coagulans and B. aerolacticus. Sequence similarity percentages ranging from 89% to 100% against reference strains underscore the taxonomic diversity of the isolates. The strong genetic affiliations evidenced in phylogenetic clustering reinforce the evolutionary distinctiveness and selection of robust probiotic candidates. The inclusion of H. coagulans expands the probiotic repertoire, highlighting its emerging significance due to unique spore-forming and acid-resistance traits. The analysis revealed two isolates (2 and 6) clustering tightly with B. subtilis, supported by high bootstrap values (>95%), confirming their affiliation with this well-characterized species known for its spore-forming ability and GRAS status. Isolate 12 is grouped within the L. helveticus clade, a species extensively used in dairy fermentations and documented for its probiotic and biopeptide-producing capacities. Isolate 18 aligned closely with B. aerolacticus, a less-studied but emerging candidate for probiotic applications due to its facultative anaerobic growth and digestive enzyme production.

| Figure 4: (a-e) Phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences showing the relationship between the isolated strains and reference strains from the NCBI GenBank database.

[Click here to view] |

Interestingly, isolate 19 was placed within a distinct phylogenetic cluster corresponding to H. coagulans, a reclassified Bacillus member gaining attention in probiotic development due to its thermal stability, spore-forming ability, and gastrointestinal robustness. The phylogenetic tree thus encapsulates the genetic heterogeneity and evolutionary lineage of the selected strains, which span the genera Lactobacillus, Bacillus, and Heyndrickxia. These findings not only reinforce the molecular identification results but also substantiate the ecological and functional diversity within goat milk microbiota, offering a promising pool of candidates for food, nutraceutical, and pharmaceutical applications.

3.6. Technological and Functional Attributes

The technological adaptability of probiotic strains is pivotal to their successful integration into food systems and therapeutic applications. Therefore, selected isolates were further evaluated for their functional enzyme production and metabolite synthesis, which contribute to both product development and host health benefits.

3.6.1. Proteolytic activity

All five selected strains demonstrated proteolytic activity on casein-supplemented agar, evidenced by halo zone formation [Table 4]. The B. subtilis isolates and B. aerolacticus displayed pronounced caseinolysis, suggesting robust protease secretion, while L. helveticus exhibited milder activity. Proteolytic competence is integral to dairy-based fermentations as it enhances protein hydrolysis, liberating bioactive peptides that may exert antihypertensive, immunomodulatory, or antioxidant effects [25]. These findings indicate their suitability for value-added dairy formulations where protein digestibility and flavor development are desired attributes.

3.6.2. Lipolytic activity

Lipase activity, assessed on tributyrin agar, was significant in both B. subtilis strains, while H. coagulans, B. aerolacticus, and L. helveticus exhibited minimal lipolytic zones [Table 4]. The observed low lipolytic activity of H. coagulans, B. aerolacticus, and L. helveticus isolates suggests limitations in their ability to contribute to lipid hydrolysis and flavor development in fermented food products. Lipolytic enzymes are instrumental in the hydrolysis of dietary fats and the generation of flavor-active compounds in fermented foods. In addition, the potential for modulating lipid digestion and absorption through host microbe interactions may expand the systemic health relevance of these strains, particularly within the context of metabolic syndrome and gut–liver axis regulation. Therefore, these strains may be less suitable for applications where significant lipolysis is desired, such as cheese ripening or flavor enhancement.

3.6.3. Diacetyl production

All five isolates produced diacetyl, a volatile compound known for its characteristic buttery aroma. Quantitative variation was evident, with B. subtilis strains exhibiting the highest levels, followed by H. coagulans and L. helveticus [Table 4]. Beyond flavor enhancement in dairy matrices, diacetyl possesses bacteriostatic properties against a range of spoilage and pathogenic organisms. This dual functionality, organoleptic and antimicrobial, strengthens the strains’ utility in fermented functional foods and bio-preservative formulations.

3.6.4. EPS production

EPS synthesis varied markedly among the isolates. H. coagulans produced the highest EPS yield (93.0 mg/L), followed by B. subtilis (Strain 1, 72.5 mg/L) and L. helveticus (58.0 mg/L), with comparatively lower outputs from B. aerolacticus and B. subtilis (Strain 2) [Table 4]. EPS-producing probiotics confer multiple advantages, including improved textural properties in fermented foods, biofilm formation for gut colonization, and health-promoting effects such as immunomodulation, cholesterol lowering, and prebiotic support for the native microbiota [26]. The high-EPS producing strains may thus serve as biofunctional agents in both food and clinical settings.

Table 5: 16S rRNA gene sequencing details of selected probiotic strains. The table presents the strain name, identified organism, 16S rRNA gene length (in base pairs), and corresponding accession and GI numbers from the NCBI database.

| Strain name | Organism | 16S rRNA gene length | Accession number | GI number |

|---|

| Bacillus subtilis strain GMI2 | Bacillus subtilis-II | 1,500 bp | PP472426.1 | 2697401519 |

| Bacillus subtilis strain GMI1 | Bacillus subtilis-I | 1,362 bp | PP472092.1 | 2697401173 |

| Lactobacillus helveticus strain GM-3 | Lactobacillus helveticus | 1,003 bp | PQ270253.1 | 2796986130 |

| Bacillus aerolacticus strain GM-1 | Bacillus aerolacticus | 1,396 bp | PQ270249.1 | 2796986124 |

| Heyndrickxia coagulans strain GM-2 | Heyndrickxia coagulans | 1,062 bp | PQ270252.1 | 2796986129 |

3.7. Probiotic Functionality

All isolates demonstrated essential probiotic traits required for gastrointestinal survival and host colonization, including high tolerance to acidic and bile conditions, strong adhesion to intestinal epithelial cells, and broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. The B. subtilis strains exhibited particularly strong bile resistance and robust enzymatic activities, while H. coagulans showed notable EPS production, supporting mucosal adherence and microbiota modulation. In addition, pronounced autoaggregation and coaggregation abilities reinforced their competitive potential against pathogenic microorganisms. Although these in vitro findings highlight promising probiotic properties – such as stress tolerance, adhesion, and enzymatic activity – it is important to note that they do not directly confirm in vivo benefits, including gut microbiome modulation or intestinal barrier protection. Such functional outcomes require further validation through animal studies and well-designed clinical trials to establish efficacy and underlying mechanisms [27,28].

4. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

This study systematically explored the probiotic potential of indigenous bacterial strains isolated from raw goat milk, employing a comprehensive selection strategy integrating morphological, biochemical, physiological, and molecular criteria. Through 16S rRNA gene sequencing and robust phylogenetic analysis, five isolates were taxonomically classified as B. subtilis (Isolates 2 and 6), L. helveticus (Isolate 12), B. aerolacticus (Isolate 18), and H. coagulans (Isolate 19). The Neighbor-Joining phylogenetic tree, supported by strong bootstrap values, confirmed their evolutionary affiliations with established reference strains, thereby validating their genetic identity and potential lineage-specific functionalities. The 16S rRNA gene sequences of all identified isolates have been deposited in the GenBank database. The corresponding accession numbers for each organism are listed in Table 5. Functionally, all selected strains demonstrated substantial resilience under simulated gastrointestinal conditions, exhibiting high acid and bile salt tolerance alongside superior adhesive and aggregation capacities, essential for mucosal colonization and competitive exclusion of enteric pathogens. Their pronounced antimicrobial spectra against E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and K. pneumoniae highlight their capacity for microbiome modulation and barrier protection, reinforcing their value as antagonistic probiotics.

Equally significant were the technological attributes exhibited by these strains. Their enzymatic profiles, characterized by robust proteolytic and lipolytic activities, support their role in enhancing nutrient bioavailability and sensory quality in fermented matrices. Moreover, the production of diacetyl and EPS confers dual functionality: improving flavor and texture in food systems, while simultaneously contributing to host health through mechanisms such as cholesterol reduction, immune modulation, and gut barrier fortification.

Collectively, these findings underscore the multifunctionality of the identified strains, positioning them as promising candidates for incorporation into functional foods, synbiotics, and next-generation probiotic formulations. Importantly, their diverse taxonomic affiliations, spanning Lactobacillus, Bacillus, and Heyndrickxia genera, expand the probiotic repertoire beyond traditional LAB, offering novel avenues for therapeutic and industrial exploitation. Nonetheless, while in vitro data provide compelling preliminary insights, translational application necessitates rigorous in vivo validation. Future investigations should include whole-genome sequencing for safety and functional gene mapping, targeted metabolomics for identifying health-promoting metabolites, and immunological assays to explore host–microbe interactions. Downstream development strategies, encompassing strain-specific formulation, microencapsulation, and clinical evaluation, will be critical for realizing their full commercial and biomedical potential. In conclusion, this study contributes valuable indigenous strains to the probiotic landscape, highlighting goat milk as a rich and underutilized reservoir of microbial diversity. The integration of these strains into functional food systems may not only enhance product quality but also promote gut and systemic health, ultimately advancing the field of microbiome-centered biotherapeutics and sustainable food innovation.

5. AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All the authors are eligible to be author as per the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) requirements/guidelines.

6. FUNDING

The authors gratefully acknowledge that the funding for this research was provided by the Pradhan Mantri Uchchatar Shiksha Abhiyan (PM-USHA), under the Multi-Disciplinary Education and Research Universities (MERU) grant, sanctioned to Sri Padmavati Mahila Visvavidyalayam, Tirupati.

7. CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no financial or any other conflicts of interest in this work.

8. ETHICAL APPROVALS

This study did not involve any animal or human experimentation; therefore, ethical approval was not required.

9. DATA AVAILABILITY

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Additional data can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

10. PUBLISHER’S NOTE

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. This journal remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliation.

11. USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (AI)-ASSISTED TECHNOLOGY

The authors declare that they have not used artificial intelligence (AI)-tools for writing and editing of the manuscript, and no images were manipulated using AI.

REFERENCES

1. Sánchez B, Delgado S, Blanco-Míguez A, Lourenço A, Gueimonde M, Margolles A. Probiotics, gut microbiota, and their influence on host health and disease. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2017;61(1):1600240.[CrossRef]

2. Maftei NM, Raileanu CR, Balta AA, Ambrose L, Boev M, Marin DB, et al. The potential impact of probiotics on human health:An update on their health-promoting properties. Microorganisms. 2024;12(2):234. [CrossRef]

3. Kandati K, Reddy AS, Nannepaga JS, Viswanath B. The influence of probiotics in reducing cisplatin-induced toxicity in Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Curr Microbiol. 2023;80(4):109.[CrossRef]

4. El Far MS, Zakaria AS, Kassem MA, Edward EA. Characterization of probiotics isolated from dietary supplements and evaluation of metabiotic-antibiotic combinations as promising therapeutic options against antibiotic-resistant pathogens using time-kill assay. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2024;24(1):303.[CrossRef]

5. Leghari AA, Shahid S, Farid MS, Saeed M, Hameed H, Anwar S, et al. Beneficial aspects of probiotics, strain selection criteria and microencapsulation using natural biopolymers to enhance gastric survival:A review. Life Sci J. 2021;18(1):30-47.

6. Islam MZ, Uddin ME, Rahman MT, Islam MA, Harun-Ur-Rashid M. Isolation and characterization of dominant lactic acid bacteria from raw goat milk:Assessment of probiotic potential and technological properties. Small Ruminant Res. 2021;205:106532.[CrossRef]

7. Ghosh T, Beniwal A, Semwal A, Navani NK. Mechanistic insights into probiotic properties of lactic acid bacteria associated with ethnic fermented dairy products. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:502.[CrossRef]

8. Chen L, Bagnicka E, Chen H, Shu G. Health potential of fermented goat dairy products:Composition comparison with fermented cow milk, probiotics selection, health benefits and mechanisms. Food Funct. 2023;14(8):3423-36.[CrossRef]

9. Lima MJ, Teixeira-Lemos E, Oliveira J, Teixeira-Lemos LP, Monteiro AM, Costa JM. Nutritional and health profile of goat products:Focus on health benefits of goat milk. In:Goat Science. London:InTechOpen;2018. 189-232. [CrossRef]

10. Bentahar MC, Benabdelmoumene D, Robert V, Dahmouni S, Qadi WS, Bengharbi Z, et al. Evaluation of probiotic potential and functional properties of Lactobacillusstrains isolated from Dhan, traditional Algerian goat milk butter. Foods. 2024;13(23):3781.[CrossRef]

11. Tran KD, Le-Thi L, Vo HH, Dinh-Thi TV, Nguyen-Thi T, Phan NH, et al. Probiotic properties and safety evaluation in the invertebrate model host Galleria mellonella of the Pichia kudriavzevii YGM091 strain isolated from fermented goat milk. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2024;16(4):1288-303.[CrossRef]

12. Castro-López C, Garcia HS, Martinez-Avila GCG, González-Córdova AF, Vallejo-Cordoba B, Hernández-Mendoza A. Genomics-based approaches to identify and predict the health-promoting and safety activities of promising probiotic strains-a probiogenomics review. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2021;108:148-63.[CrossRef]

13. Ikombayev T, Ospanova A, Omarova A, Horá?kováŠ, Tuganbay A, Kassenova G, et al. Functional properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from raw goat milk and cottage cheese. J Agric Food Res. 2025;21:101822.[CrossRef]

14. Siriwardhana J, Rasika DM, Yapa D, Weerathilake WA, Priyashantha H. Enhancing probiotic survival and quality of fermented goat milk beverages with bael (Aegle marmelos) fruit pulp. Food Chem Adv. 2024;5:100792.[CrossRef]

15. Nicolas GM, Ma S. Effects of Heyndrickxia coagulans probiotics in the human gut microbiota and their health implications:A review. Food Wellness. 2025;1(1):100003.[CrossRef]

16. Cappuccino JG, Sherman N. Microbiology:A Laboratory Manual. San Francisco:Pearson/Benjamin Cummings;2005. 507.

17. Collado MC, Meriluoto J, Salminen S. Role of commercial probiotic strains against human pathogen adhesion to intestinal mucus. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2007;45(4):454-60.[CrossRef]

18. Tuomola EM, Ouwehand AC, Salminen SJ. The effect of probiotic bacteria on the adhesion of pathogens to human intestinal mucus. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1999;26(2):137-42.[CrossRef]

19. DuBois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. AnalChem. 1956;28(3):350-6.[CrossRef]

20. Cruickshank R, Duguid JP, Marmion BP, Swian RA. Medical Microbiology Churchill Livingstone. Vol. 11. New York:Elsevier;1975. 585.

21. Bindu A, Lakshmidevi N. Identification and in vitro evaluation of probiotic attributes of lactic acid bacteria isolated from fermented food sources. Arch Microbiol. 2021;203:579-95.[CrossRef]

22. Kaewarsar E, Chaiyasut C, Lailerd N, Makhamrueang N, Peerajan S, Sirilun S. Effects of synbiotic Lacticaseibacillus paracasei, Bifidobacterium breve, and prebiotics on the growth stimulation of beneficial gut microbiota. Foods. 2023;12(20):3847.[CrossRef]

23. Bisht V, Das B, Hussain A, Kumar V, Navani NK. Understanding of probiotic origin antimicrobial peptides:A sustainable approach ensuring food safety. NPJ Sci Food. 2024;8(1):67.[CrossRef]

24. Müller M, Mayrhofer S, Sudjarwo WA, Gibisch M, Tauer C, Berger E, et al. Antimicrobial peptide plectasin recombinantly produced in Escherichia coli disintegrates cell walls of Gram-positive bacteria, as proven by transmission electron and atomic force microscopy. J Bacteriol. 2025;207:00456-24.[CrossRef]

25. Ali MA, Kamal MM, Rahman MH, Siddiqui MN, Haque MA, Saha KK, et al. Functional dairy products as a source of bioactive peptides and probiotics:Current trends and future prospectives. J Food Sci Technol. 2022;59(4):1263-79.[CrossRef]

26. Pourjafar H, Ansari F, Sadeghi A, Samakkhah SA, Jafari SM. Functional and health-promoting properties of probiotics'exopolysaccharides;Isolation, characterization, and applications in the food industry. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2023;63(26):8194-225.[CrossRef]

27. Vinderola G, Gueimonde M, Gomez-Gallego C, Delfederico L, Salminen S. Correlation between in vitro and in vivo assays in selection of probiotics from traditional species of bacteria. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2017;68:83-90.[CrossRef]

28. Ma T, Shen X, Shi X, Sakandar HA, Quan K, Li Y, et al. Targeting gut microbiota and metabolism as the major probiotic mechanism-an evidence-based review. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2023;138:178-98.[CrossRef]

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material can be accessed at the link here: [https://jabonline.in/admin/php/uploadss/1435_pdf.pdf]