1. INTRODUCTION

Hydrophobins (HPs) are surface-active proteins mainly found in filamentous fungi and mushrooms. They are small proteins with 100–150 amino acids with the conserved domain of eight cysteine residues [1]. They work as a functional and structural protein for the life cycle of fungi. Roles include lowering of water surface tension for breaching of the hyphae to grow in the air, and layers on the surface of the fruiting bodies to make them hydrophobic, which makes them robust to spread in the environment, helps fungi to attach to a hydrophobic surface, and also plays a role in invading plants and symbiotic association with algae and cyanobacteria [2]. Due to their foaming property and amphipathic nature, HPs can be used in various industrial applications such as food foams, industrial emulsions, drug delivery systems, the design of Biosensors, can be used as antifouling agents for biomedical devices, and many more. HPs isolated from mushrooms are more important as they are isolated from GRAS (Generally Regarded as Safe) strains. Mushroom species such as Schizophyllum commune, Pleurotus ostreatus, Agaricus bisporus, and Pisolithus tinctorius have already been explored for the isolation and identification of hydrophobins such as SC3, Vmh2, ABH1, and ABH2, HYDPt-1, respectively [3]. The GRAS nature of mushrooms always encourages the isolation of new hydrophobins with exclusive properties that can be explored in novel industrial applications. The above-mentioned HPs are currently being explored for various industrial applications. In this study, HPs such as Hydph6, Hydph7, and Hydph16 have been detected 1st time in a protein sample along with Vmh2 and Vmh3-1 from P. ostreatus. Prior studies were mainly focused on the genetic level expression of these proteins, the development of mutant strains, and studying the impact of their absence on the physiological development of P. ostreatus [4,5]. The current study was a clear indication of the role of these proteins in mycelia, as these were isolated at the protein level from mature mycelium. Studies performed for HPs in P. ostreatus majorly focused on the genetic level expression and integration with phylogenetic analysis to compare the roles of HPs with other species [6]. Proteome isolation and identification using a gold standard method like O-HR-LC-MS/MS was attempted 1st time in this area. All these HPs were found to have close molecular weights (Mws) and were difficult to purify without recombinant production methods. Before going to extensive recombinant production in silico characterization, structure modeling, and docking studies were carried out. These experiments were considered for the preliminary screening of the most biologically active and structurally suitable HP for industrial applications, out of these five to consider further for the recombinant production process.

The advancements in computational biology have helped provide powerful tools for structural and functional analysis of newly identified proteins. In the context of hydrophobins, in silico techniques have enabled a detailed exploration of their molecular properties, interactions, and potential industrial applications. A critical step in in silico protein analysis is the validation of predicted models to ensure their reliability and accuracy. In the case of hydrophobins, model validation served as a cornerstone for assessing the quality of the three-dimensional structures generated through computational methods. Physicochemical properties of all HPs were studied using ProtParam and ProtScale. HPs are known to be membrane proteins of fungi; to confirm their function, localization, and stability in membranes, transmembrane localization was studied using Deep Transmembrane Helices Hidden Markov Model (TMHMM)-1.0. Secondary structure was predicted using Phyre2, and Modeller was used to predict the three-dimensional structure. All structures were validated systematically using suitable tools. Recent mutational studies on P. ostreatus to understand the role of Vmh2, Vmh3, and Hydph16 indicated that all these HPs are crucial for the formation of the cell membrane, the thickness of the membrane, and are found to be responsible for the hydrophobicity of the membrane [4,5]. In silico docking studies were carried out in this work to verify the function of all these detected HPs in membrane formation and hydrophobicity. The docking study was carried out with chitin, the most abundant part of the fungal membranes. This study will continue for the recombinant production of all these HPs and their physical characterization for industrial applications.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Culture Conditions

P. ostreatus (National Collection of Industrial Microorganisms [NCIM]: 1200) was procured from the NCIM in Pune, Maharashtra, India, and subcultured periodically on Potato dextrose agar and maintained at 4°C. To isolate HPs, P. ostreatus was grown in static liquid culture conditions for 10–13 days by inoculation of 6 agar circles of mycelium of 1 cm diameter into each 100 mL fermentation medium contained in a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask. Fermentation media compositions were (g/L) of yeast extract, 4, malt extract, 10, sucrose, 4, and pH 5.5 [7]. The process of fermentation was carried out at 28°C, and densely grown mycelia on the surface of the media were collected for the purification of HPs.

2.2. Purification of Hydrophobins and Mw Determination using Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

Extraction of HPs was carried out from the mycelia of P. ostreatus. Considering the SDS insoluble nature of HPs, mycelia were treated with 2% SDS in a boiling water bath for 10 min. This process was repeated thrice, and the treated mycelia were washed with water and finally with 60% ethanol. Mycelia was freeze-dried and stored for further use. To isolate HPs present on mycelial membranes, biomass was treated with 99% Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in a bath sonicator for 15 min. The supernatant was collected and dried in a stream of air. This dried material was supposed to contain HPs and was dissolved in 60% ethanol. The supernatant containing HPs was collected by centrifugation at 4°C for 20 min at 3441×g. This hydrophobin-containing solution was freeze-dried and dissolved in double-distilled water by adjusting its pH to 7. The sample was further used for Mw determination and HP primary sequence identification. SDS-PAGE was carried out in a vertical unit (Orange, VMR0007) using a 5% polyacrylamide stacking gel and a 12% resolving gel [8]. The protein sample (5μg/lane) was loaded by mixing with a 5X sample loading buffer (1 M Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 14.4 mM 2-Mercaptoethanol, 50% v/v Glycerol, 10% SDS, 1% Bromophenol Blue). After a run time of 2–3 h at 100V, gels were soaked overnight in Coomassie Brilliant Blue G250. The process of destaining was carried out to get visible protein bands on the gel. To determine the Mw of the protein bands, a broad range of SDS-PAGE Mw markers (Himedia) was used. Densitometry analysis was carried out to calculate the concentration of protein present in each protein band on SDS-PAGE using ImageJ software.

2.3. Protein Identification by OHR-LC-MS/MS

The proteomic approach was used to identify hydrophobins present in protein samples. Protein bands were excised from polyacrylamide gels and washed with distilled water. In-gel trypsin digestion was carried out using a trypsin: Protein ratio of 1:10 w/w. An extraction buffer (0.2% formic acid in 66% acetonitrile) was used to extract almost all digested peptides. This protein extract was purified using Zip-Tip C18 pipette tips (Millipore, USA) to remove salts from the sample. This peptide mixture was separated on a PepMap RSLC C18 analytical column of the UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific Pvt. Ltd). Segregated peptide molecules were analyzed in a Q Exactive Plus Orbitrap Mass spectrometer (MS). Peaks generated in Orbitrap- LC-MS were further identified in the MS/MS mode of the Q Exactive Plus-Orbitrap MS instrument. Thermo Proteome Discoverer 2.2 software was used for the analysis of raw data through LC-MS and MS/MS spectra. Mascot database searching was performed by the Sequest HT search engine to identify the protein found in each peak. According to the requirements, settings were used, such as Trypsin/P enzyme setting, false discovery rate (FDR) of 1%. Modification settings were made for the detection of modifications such as oxidation (M), carbamidomethyl (C). Missed cleavage was detected as 1 or sometimes 2 in a few peptides. Raw data collected from the system were matched with the database of P. ostreatus for the identification of hydrophobins. Identified protein information, such as Mw, amino acid sequence, isoelectric point (pI), and modifications like carbamidomethylation of cysteine, was furnished by the system.

2.4. Computational Analysis of Identified HPs

Computational analysis of identified HPs, Vmh2, Vmh3-1, Hydph6, Hydph7, and Hydph16 was carried out using the following tools.

2.4.1. FASTA sequence retrieval

The amino acid sequences used in the in silico analysis were sourced from the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org). The protein under scrutiny was natively sourced from the organism, P. ostreatus. The hydrophobins that were identified are Hydph6, Hydph7, Hydph16, Vmh2, and Vmh3-1. The accession IDs of these hydrophobins are A0A067PCX8, A0A067P1E6, A0A067P943, A0A067N4H9, and Q8WZI4, respectively. The FASTA sequences are accessed using TrEMBL.

2.4.2. Physicochemical properties

Expasy servers were used to measure the physical, chemical, and structural properties. The ProtParam (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) tool in the Expasy suite was used for computing various physicochemical properties of a protein from its amino acid sequences to understand protein solubility, stability, and expression feasibility in different systems. Using ProtParam, Mw, pI, number of amino acids, Instability index, aliphatic index (AI), grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY), and half-life of the structure were deduced.

The ProtScale (https://web.expasy.org/protscale/), another Expasy tool, was used for membrane protein prediction, solvent accessibility, and understanding structural motifs of selected hydrophobins. The seven properties analyzed using ProtScale were hydropathicity, polarity, relative mutability, average flexibility, transmembrane tendency, percentage of accessible residues in the structure, and percentage of buried residues in the structure [9].

2.4.3. Signal peptide prediction and transmembrane sub-localization

The presence of signal peptide in secreted protein was examined using the in silico program Signal P-5.0 (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/SignalP-5.0/). The Deep TMHMM-1.0 (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/DeepTMHMM-1.0/) server detected alpha helices and beta sheets of proteins spanning the lipid bilayer. The Bologna Unified Subcellular Component Annotator server was used to anticipate the subcellular localization and protein features.

2.4.4. Protein structure modeling and evaluation

The secondary structures of hydrophobins were predicted using the Phyre2 server (http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/~phyre2/) [10]. In silico homology modeling was used for the construction of the 3D structure of the protein. Modeller 9.11 was used to generate 3D structures based on the comparative modeling technique. The FASTA format amino acid sequences of Hydph6, Hydph7, Hydph16, Vmh2, and Vmh3-1 were selected from the NCBI database and submitted to the BLASTp server for the identification of suitable templates [11,12]. The E-value score was recognized as an index of similarity between the target and template proteins [13]. Pairwise sequence alignment of the protein was done with its template to recognize the structurally conserved region, using the ClustalW tool [14]. The Gonnet matrix algorithm is used by the ClustalW server to detect conserved motifs and minimize the atomic gaps. A ratio of the number of identical residues in the alignment and the total number of residues of the target was used to calculate the percentage (%) identity of the alignment. The 3D structures of the target were generated using Modeller 9.11 [15]. To study the quality of the generated structures, computational protocols like PROCHECK for Ramachandran plots [16] and the protein structural analysis (ProSA) tool were used.

2.4.5. Protein–protein interactions

To investigate protein–protein interactions among hydrophobins, the search tool for the retrieval of interacting genes/proteins (STRING) database was employed (https://string-db.org/). The protein sequences of hydrophobins were entered into STRING to construct interaction networks for elucidating functional associations.

A stringent confidence score threshold of 0.700 was established to ensure the accuracy of the predicted interactions. This strategy enabled the identification of potential interaction partners and functional pathways, thus providing a more comprehensive understanding of the biological significance of hydrophobins under this study.

2.4.6. Protein docking analysis

Molecular docking was performed using CB-Dock2, a cavity-detection-guided blind docking tool that integrates AutoDock Vina (v1.2.0) as its docking engine [17]. CB-Dock2 automatically detects potential ligand-binding cavities on the protein surface and defines the search space (grid box center and size) based on these predicted pockets. As such, the search space was not manually defined but algorithmically set by the server to ensure docking within biologically relevant regions.

The exhaustiveness parameter, which controls the depth and thoroughness of the conformational search in AutoDock Vina, was used at its default value of 8, as CB-Dock2 does not provide an option for manual adjustment of this parameter [18]. Docking studies were carried out for HPs Vmh3-1, Vmh2, Hydph6, Hydph7, and Hydph16 with Chitin. Previous studies emphasized the roles of HPs in cell wall formation [4,5]. Docking of HPs detected in this study with chitin helped to enhance understanding of the role of these HPs in cell wall formation. The structure of Chitin was retrieved from the ZINC database (ZINC 24425833) (https://zinc.docking.org/) in SDF format. Beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase, Chitinase A1, Chitin-binding protein 21 (CBP21), Wheat Germ Agglutinin-A Chitin-Binding Lectin, were used as positive controls.

2.4.7. Phylogenetic relationship of hydrophobins

The phylogenetic analysis of hydrophobin proteins involved performing a multiple-sequence alignment with ClustalW (https://www.genome.jp/tools-bin/clustalw) to identify conserved regions and variations within the sequences. Phylogenetic relationships were inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method in Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA 11). After the alignment, the sequences were imported into the MEGA 11 software to construct a phylogenetic tree. A Neighbor-Joining algorithm was employed, along with bootstrap analysis, to assess the reliability of the resulting tree. The evolutionary distances were calculated using the Neighbor-Joining method. The tree was constructed based on 1000 bootstrap replicates to assess the reliability of the inferred clades. Gaps and missing data were treated using the pairwise deletion option. The generated phylogenetic tree provided important insights into the evolutionary relationships and divergence patterns among hydrophobin proteins, aiding in their classification and functional predictions.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Extraction and Identification of HPs from P. ostreatus using a Proteomic Approach

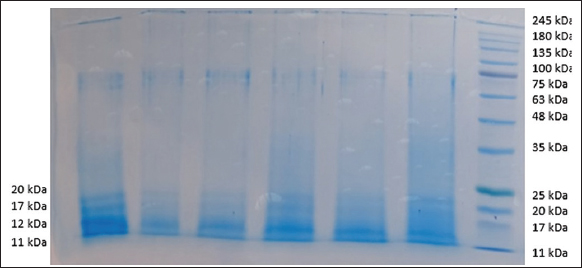

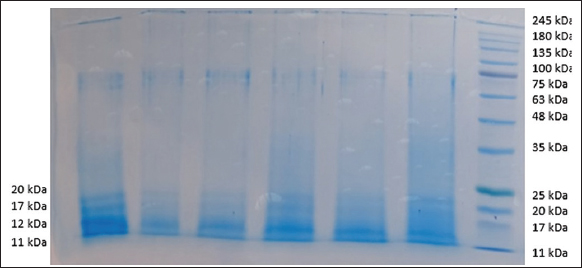

Hydrophobins extracted from P. ostreatus were analyzed using SDS-PAGE. The prominent protein bands at 11 kDa, 12 kDa, 17 kDa, and 20 kDa were observed in the polyacrylamide gel [Figure 1]. Lane number one has shown all bands, and other lanes showed faint bands of 17 and 20 kDa, while 11 and 12 kDa bands are prominently seen in all the lanes.

| Figure 1: SDS-PAGE analysis of proteins extracted from mycelia of Pleurotus ostreatus.

[Click here to view] |

All the protein bands of 11 kDa, 12 kDa, 17 kDa, and 20 kDa were excised from the gel and identified by O-HR-LC-MS/MS. In this proteomic analysis, hydrophobins Vmh2, Vmh3-1, Hydph6, Hydph7, and Hydph16 were identified. Table 1 depicts the identified HPs with their amino acid sequence, Mw, and pI. Out of which Vmh2 was previously isolated, identified, and characterized for various industrial applications [19]. In our previous study, Vmh3-1 has been isolated from the same species [20]. HPs Hydph6, Hydph7, and Hydph16 were detected and characterized 1st time in this study. According to the genetic studies, the Hyph6 gene was found to be stable in three common monokaryotic strains (PC15, Pm007, and Pm039) [6]. The function of Hydph6 was not studied at the genetic level. Hydph7 was found to play a role in the development of the fruit body [21]. Gene disruption analysis suggested that Vmh2 and Vmh3 affect hyphal hydrophobicity [5]. Hydph16 was also found in the hyphal cell wall, but the function of this HP is different from Vmh2 and Vmh3. Gene disruption study suggested Hydph16 plays a role in the correct morphology of hyphae [4]. These predicted functions should be verified by studying structural and functional properties. Computational analysis of all HPs was carried out using different tools. Each HP present in P. ostreatus is a potential molecule for industrial application. Computational analysis was carried out using different in silico tools to understand the characteristics of these HPs.

Table 1: Identification of Hydrophobins from mycelia of Pleurotus ostreatus.

| Accession Number | Protein name | Coverage % | No. of unique peptides | PSMs | Amino Acids | Molecular weight (kDa) | Calculated pI |

|---|

| A0A067PCX8 | Hydph 6 | 19 | 1 | 3 | 114 | 11.4 | 5.19 |

| A0A067P1E6 | Hydph 7 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 109 | 11.1 | 7.88 |

| A0A067P943 | Hydph 16 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 136 | 13.7 | 8.34 |

| A0A067N4H9 | Vmh2 | 17 | 1 | 2 | 111 | 11.2 | 4.91 |

| Q8WZI4 | Vmh3-1 | 54 | 12 | | 108 | 11.15 | 7.5 |

3.2. Computational Analysis: Use of Bioinformatics Tools for Analysis of Hydrophobins

3.2.1. Physicochemical characterization of hydrophobins of P. ostreatus

The physicochemical characteristics of hydrophobins Vmh2, Vmh3-1, Hydph6, Hydph7, and Hydph16 were studied using ProtParam, and the analysis of results is displayed in Table 2. The instability index results showed that hydrophobins Vmh2, Hydph6, and Hydph16 were unstable (with an index value of >40), while Vmh3-1 and Hydph7 were found to be stable (with an index value of <40). The AI is a physicochemical characteristic that reflects the thermal stability of a protein, especially under extreme conditions. It quantifies the proportion of space occupied by aliphatic side chains (Ala, Val, Ile, and Leu) within a protein sequence. The AI showed that the HPs are stable at high temperatures. This can be verified as these HPs were found rich in alanine, valine, leucine, and isoleucine.

Table 2: Physicochemical parameters of hydrophobins studied using Protparam.

| Parameter | Hydrophobin name |

|---|

|

|---|

| Hydph 6 | Hydph 7 | Hydph 16 | Vmh2 | Vmh3-1 |

|---|

| Molecular weight (kDa) | 11455.4 | 11106.92 | 13679.01 | 11218.32 | 11149.93 |

| pI | 5.04 | 8.14 | 8.72 | 5.77 | 7.48 |

| Number of amino acids | 114 | 109 | 136 | 111 | 108 |

| Instability index | 45.94 | 33.24 | 44.93 | 40.15 | 39.37 |

| Aliphatic index (AI) | 112.11 | 100.09 | 101.1 | 122.07 | 94.91 |

| Grand average of hydropathicity | 0.662 | 0.436 | 0.417 | 0.996 | 0.399 |

| Half-life | 30 h (mammalian reticulocytes, in vitro). >20 h (yeast, in vivo). >10 h (Escherichia coli, in vivo). |

The fundamental properties such as average flexibility, polarity, relative mutability, hydropathy, transmembrane tendency, % buried residues, and % accessible residues, were retrieved from ProtScale and are displayed in Table 3. The maximum hydropathicity is displayed by Hydph16 (3.144), while Hydph7 has shown the least hydropathicity of 1.233. In a group, Hydph7 showed maximum mutability with a scale of 102.23 at the amino acid position 45. All other HPs showed a mutability scale below 95 at different amino acid scales. All hydrophobins showed a polarity range from 5.6 to 10.21. Flexibility of all HPs was in the range of 0.38–0.5. It was of interest to notice that the index of % residues buried was maximum between 10.57% and 11.33%. The accessibility scale of all HPs was less than the scale of buried residues, indicating the structural stability of the HPs.

Table 3: ProtScale evaluation of HPs isolated from Pleurotus ostreatus.

| Hydrophobin | Hydropathicity | Mutability | Polarity | Flexibility | Transmembrane tendency | % residue accessible | % residue buried |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Min. | Max. | Min. | Max. | Min. | Max. | Min. | Max. | Min. | Max. | Min. | Max. | Min. | Max. |

|---|

| Hydph 6 | −1.62 | 2.67 | 63.22 | 92.45 | 6.31 | 9.99 | 0.38 | 0.48 | −1.46 | 0.99 | 4.26 | 7.83 | 3.72 | 10.57 |

| Amino Acid Position | 96 | 59 | 59 | 30 | 59 | 50 | 19 | 45, 46 | 96 | 50 | 105 | 45, 46 | 95 | 59 |

| Hydph 7 | −1.28 | 1.23 | 61 | 102.22 | 6.47 | 10 | 0.37 | 0.49 | −1.47 | 1.15 | 4.12 | 8.17 | 3.55 | 11.17 |

| Amino Acid Position | 26 | 9 | 84 | 45 | 9 | 41 | 12 | 80 | 41 | 9 | 31 | 43, 44 | 37 | 75 |

| Hydph 16 | −1.97 | 3.14 | 50.55 | 93.88 | 5.98 | 10.01 | 0.38 | 0.48 | −1.54 | 1.37 | 4.41 | 7.44 | 4.25 | 11.17 |

| Amino Acid Position | 52 | 82 | 97, 98 | 70 | 83 | 70 | 11 | 52 | 52 | 82 | 127 | 50 | 51 | 80 |

| Vmh2 | −1.30 | 3.13 | 52.22 | 91.33 | 5.62 | 9.31 | 0.38 | 0.48 | −1.19 | 1.36 | 3.56 | 7.21 | 4.30 | 11.18 |

| 26 | 8 | 11 | 42 | 8 | 42 | 8 | 29 | 26 | 8 | 7 | 42 | 26 | 56 |

| Vmh3-1 | −2.13 | 2.52 | 66.66 | 95.66 | 6.83 | 10.21 | 0.38 | 0.48 | −1.71 | 0.88 | 4.32 | 7.62 | 3.38 | 11.33 |

| 26 | 10 | 72 | 27 | 17 | 39 | 12 | 58 | 37 | 10 | 4 | 47 | 26 | 11 |

3.2.2. Signal peptide prediction and sub-localization

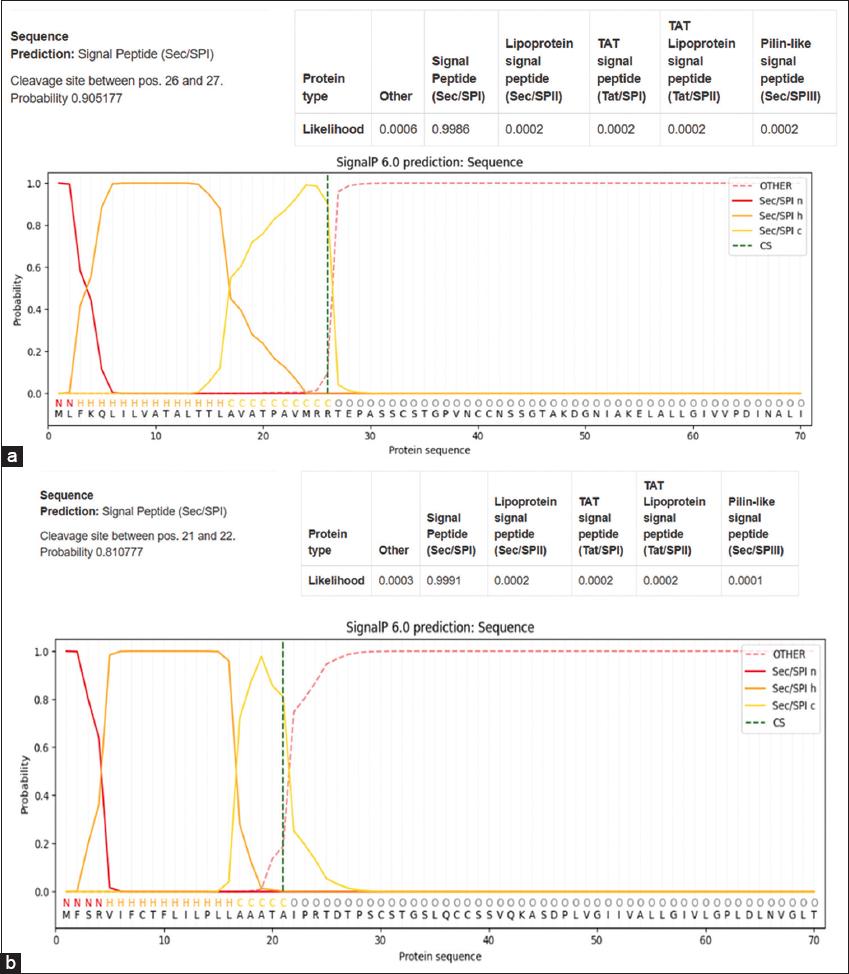

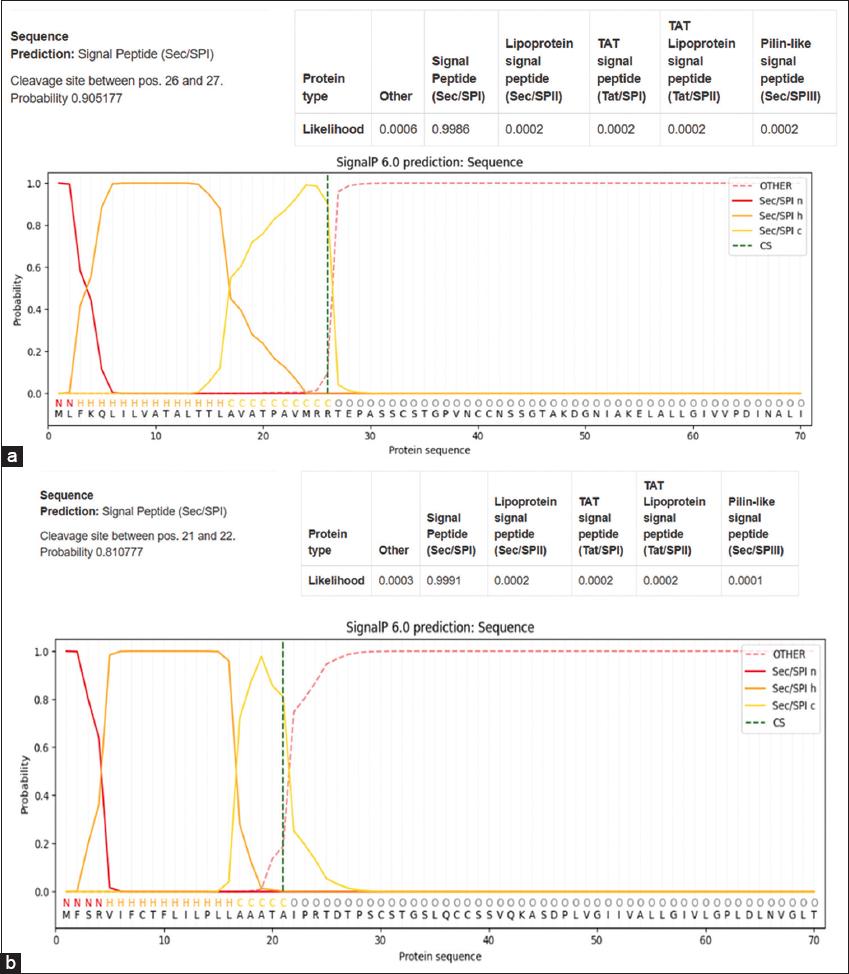

The signal peptides of identified hydrophobins Hydph6, Hydph7, Hydph16, Vmh 2, and Vmh 3-1 were predicted using the SignalP-5.0 server. The results showed that for Hydph6, the cleavage site lies between the 19th and 20th amino acids, and the signal peptide probability was calculated to be 0.9986 [Figure 2a]. For Hydph7 and Vmh3-1, the cleavage site was estimated to be between the 23rd and 24th amino acid, and both showed the signal peptide probability of 0.999 [Figures S1 and S3]. The cleavage site for Hydph16 was estimated to be between amino acids at positions 19 and 20 [Figure S2]. The cleavage site for Vmh2 was estimated to be between the 21st and 22nd amino acid, with the probability of signal peptide being 0.991 [Figure 2b]. The probabilities for the hydrophobins not having any signal peptide were also seen to be 0.0142 for Hydph6 and 0.0003 for Hydph7, Hydph16, Vmh3-1, and Vmh2.

| Figure 2: (a) Signal peptide prediction of Hydph6. (b) Signal Peptide prediction of Hydph7.

[Click here to view] |

The transmembrane regions were predicted using the Deep TMHMM 1.0 site. Figure 3 represents predicted transmembrane regions for Hydph6; figures of other proteins were not included here and provided as supplementary information [Figures S4-S7]. The results showed that none of the hydrophobins showed the presence of transmembrane regions, suggesting they were likely to be secreted or stored in the membrane organelles. Unlike integral membrane proteins, these hydrophobins lacked true transmembrane α-helices that span lipid bilayers, self-assembled into amphipathic monolayers at interfaces (water–air, water-hydrophobic surfaces), and interacted transiently with membranes, forming hydrophobic coatings [22]. This indicates that hydrophobins may not have real transmembrane helices, but their hydrophobic parts play a key role in creating hydrophobic films on fungal spores and other structures [23]. These films help fungi withstand drying out and tough environmental conditions. In addition, hydrophobins can self-organize into well-structured amyloid-like formations [24]. These formations act like biofilms, protecting the fungi [25].

GPI anchoring prediction results indicated that none of the tested hydrophobins (Vmh2, Vmh3-1, Hydph6, and Hydph7) were GPI-anchored, with high likelihood scores ranging from 0.918 to 0.992, suggesting they did not attach to membranes through GPI anchors.

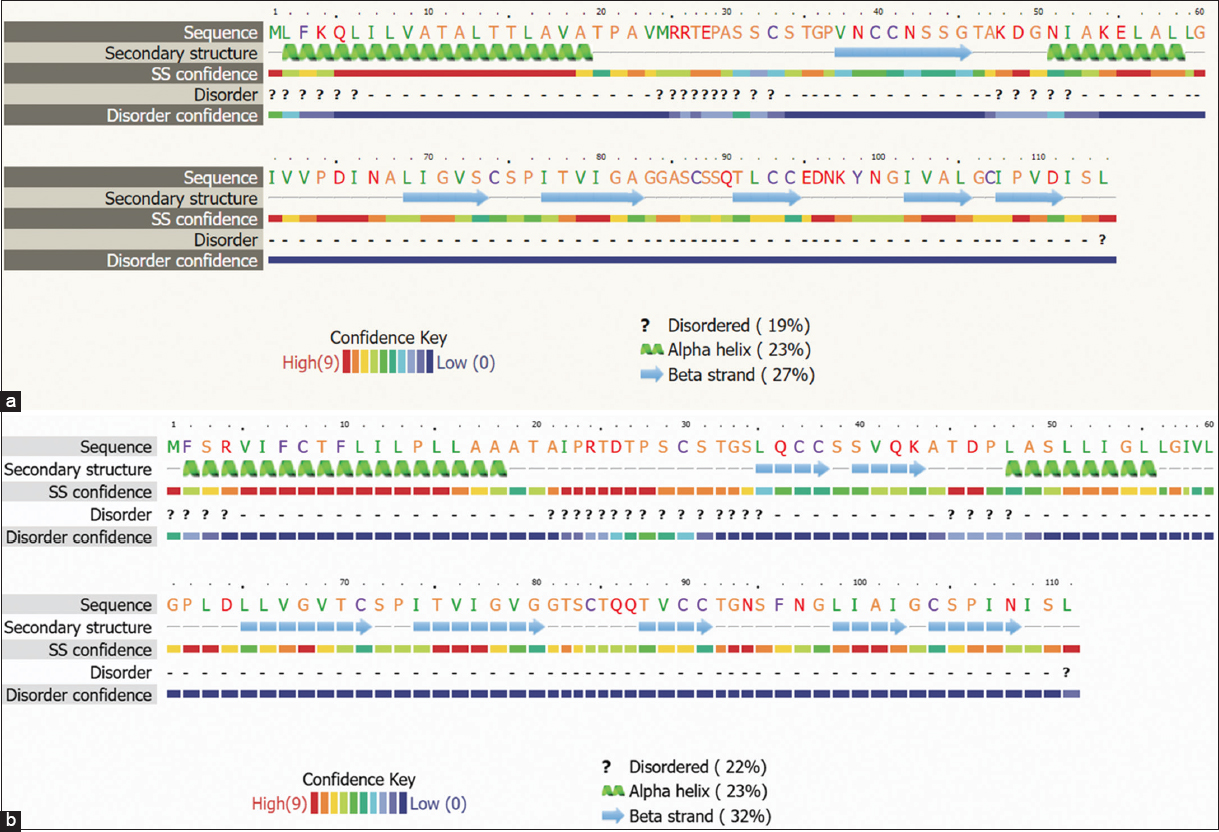

3.2.3. Hydrophobin structure prediction using Phyre2

In the study, both Phyre2 and MODELLER were employed to predict the structure of the target protein. Phyre2’s analysis provided valuable insights, particularly in identifying potential templates and modeling regions with low sequence similarity. By integrating Phyre2’s broad template detection capabilities with MODELLER’s precise modeling techniques, more comprehensive and reliable protein structure prediction was achieved.

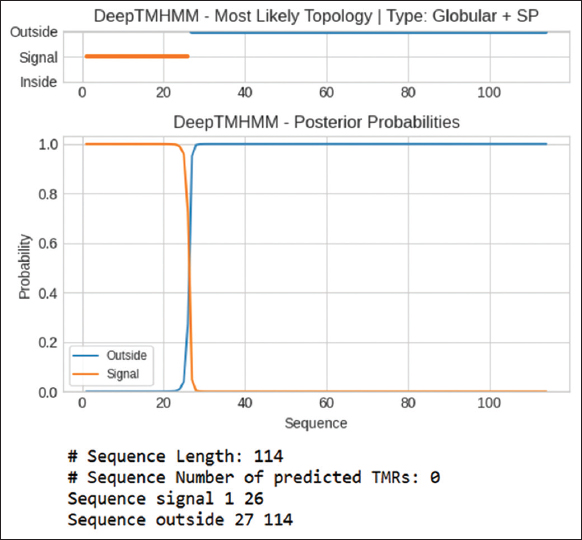

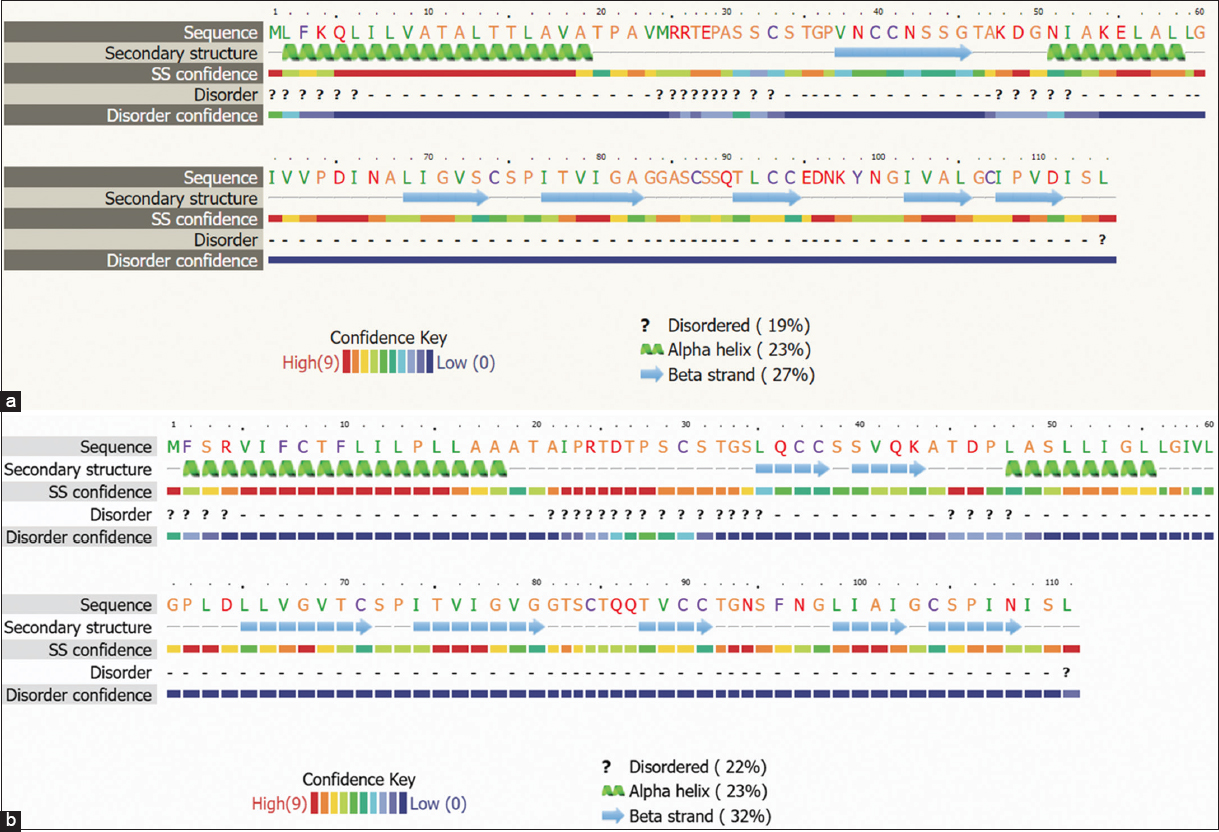

The functionality and various other properties of the proteins are dependent on their two and three-dimensional structures. The 2D structures of Hydph6, Hydph7, Hydph16, Vmh-2, and Vmh-3-1, were predicted using the Phyre2 server. It also helped to determine the percentage of alpha-helices, beta strands, and random coils present in the selected hydrophobins. The results of 2D structures showed that Hydph6 and Vmh2 had the highest percentage of alpha-helices [Figure 4a and b] while Vmh3-1 and Hydph7 showed the highest percentage of beta-strands and disordered coils [Figure S8 and S10].

| Figure 4: (a) Predicted Secondary structure of Hydph6. (b) Predicted Secondary structure of Vmh2

[Click here to view] |

Hydrophobins Vmh2, Hydph6, and Hydph16 [Figure 4a, b and Figure S9] exhibited a balanced proportion of disordered regions, alpha helices, and beta strands, suggesting moderate flexibility, stability, and self-assembly capability.

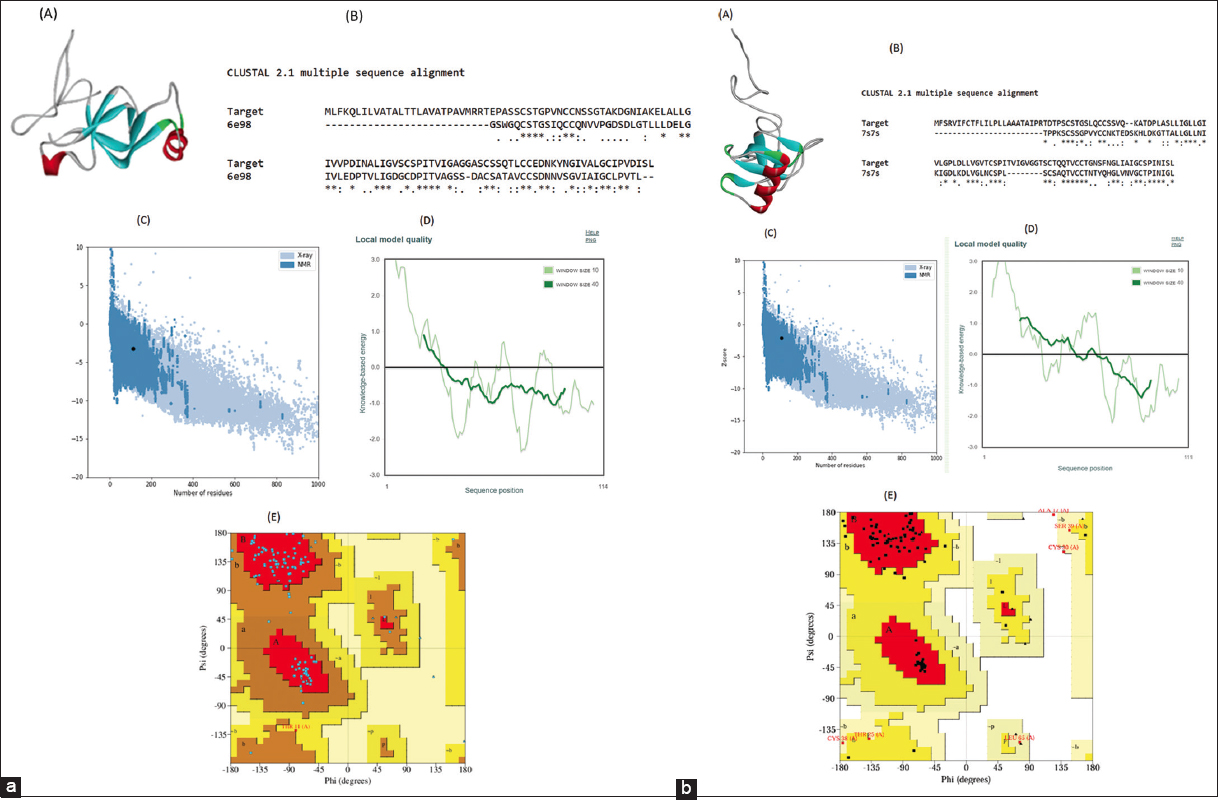

3.2.4. Hydrophobin structure prediction using Modeller 9.11

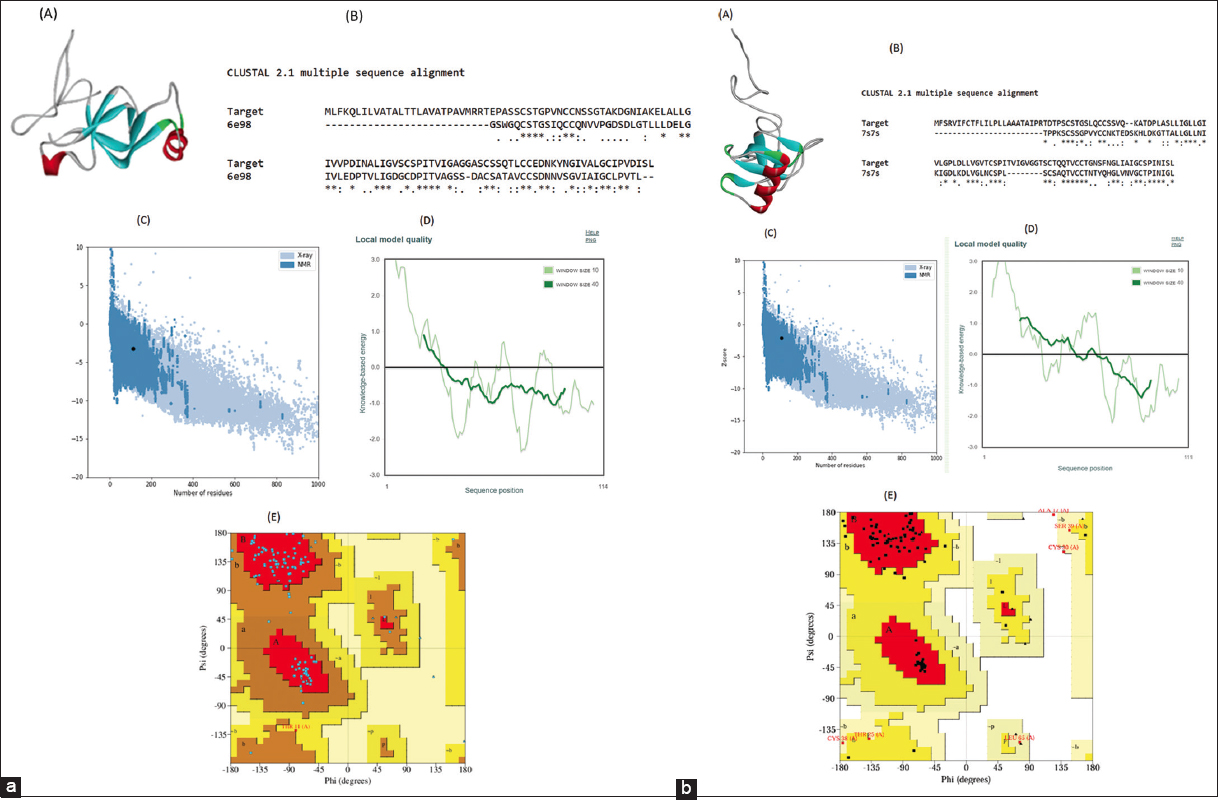

HP structures were designed using Modeller 9.11. The Z-scores of Vmh2 and Vmh3-1 were found to be below the true value, suggesting that their energy distributions align more closely with those derived from random conformations. In contrast, the Z-scores of Hydph6 and Hydph7 were predicted to be −3.01 and −3.17, respectively, indicating slightly more negative energies but potentially still within acceptable ranges for reliable protein structures. The predicted structures of Hydph6 and Vmh2 are presented in Figure 5 [Figure 5 a and b]. The predicted structures of Hydph7, Hydph16, and Vmh3-1 have been included in the supplementary document [Figures S11, S12 and S13]

| Figure 5: (a): Structure analysis and validation of (A) predicted 3D structure of HYDPH6 Hydrophobin protein by Modeller 9.11. (B) pairwise sequence alignment with 6e98 using ClustalW, where the conserved amino acid residues are elucidated as (), highly similar residues as (:), and weakly similar residues as (.). (C) ProSA-Z-score plot shows the overall model quality Z score, i.e., −3.23, (D) Local model quality. (E) Ramachandran plot analysis of 3D structure of HYDPH6 Hydrophobin, where the red region defines the most favorable area of residues; the yellow region is additionally allowed; and generously allowed residues in the light-yellow region. (b) Structure analysis and validation of (A) predicted 3D structure of Vmh2 protein by Modeler 9.11. (B) pairwise sequence alignment with 7s7s using ClustalW, where the conserved amino acid residues are elucidated as (), highly similar residues as (:) and weakly similar residues as (.). (C) ProSA-Z-score plot shows the overall model quality Z score i.e. −2.13, (D) Local model quality. (E) Ramachandran plot analysis of 3D structure of Vmh2, where the red region defines the most favorable area of residues; the yellow region is additionally allowed; and generously allowed residues in the light-yellow region.

[Click here to view] |

The Ramachandran plot analysis [Figure 5a and b] revealed that for Vmh3-1 and Vmh2, 89.5% of residues are in the most favored regions, indicating a well-folded and stable structure. In addition, 9.5% of residues are in the allowed regions, while 1.1% fall in the disallowed regions, suggesting minor deviations. For Hydph7, 79.6% of residues are in the most favored regions, with 18.3% in the allowed regions, indicating a slightly less optimal conformation. For Hydph6, 87.5% of residues are in the most favored regions, suggesting a generally stable structure with fewer deviations. For Hydph16, the majority of residues (79.8%) fell within the most favored regions, and only 3 residues (2.9%) were in the disallowed region.

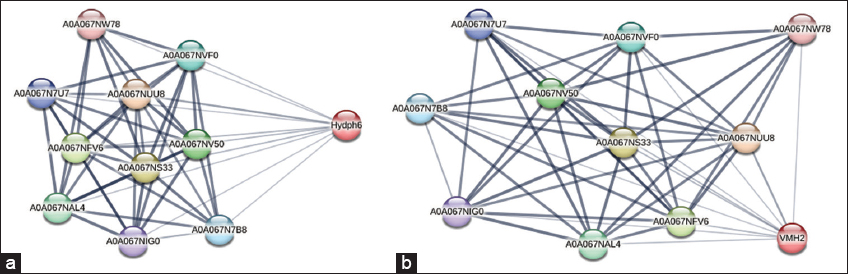

3.2.5. Protein–protein interactions

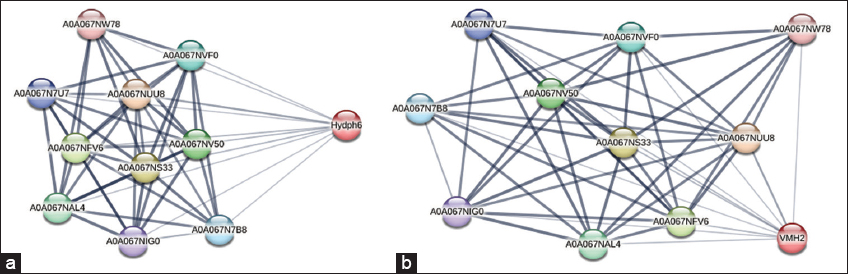

The interaction of hydrophobins Hydph6, Vmh 2, Hydph7, Hydph16, and Vmh-3-1 was carried out using the STRING platform [Figures 6a, b, and S14-S16]. HP Vmh3-1 [Figure S16] had shown the highest score of interaction with a score of 0.816. Most of the interactions of Vmh3-1 were found with proteins involved in the regulated transport of other proteins, RNA, and biomolecules such as the nuclear pore complex (NPCs) protein, Ran BD1 domain-containing protein, and some uncharacterized proteins. Interactions of Hydph16 [Figure S15] were found to be similar to Vmh3-1 within the biological system of P. ostreatus. This HP was also found interacting with transporter proteins such as NPCs and Ran BD1 domain-containing protein. The interaction score was high in the range of 0.688–0.816. HP Vmh2 [Figure 6b] has shown riveting interactions with proteins like Peptidase C50 domain-containing protein, which are also called separases. Peptidase C50 plays a role in cell division, protein processing, and cleavage. The exact type of interaction between these two proteins is not clear, but Peptidase C50 may be playing a role in the modulation and processing of HP Vmh2. Vmh2 has also shown interaction with HORMA domain-containing protein involved in crucial regulation of chromosome organization and segregation, with a good score of 0.507. Interactions of Hydph6 [Figure 6a] were exactly similar to Vmh2, suggesting similar roles in the development of P. ostreatus. Hydph7 [Figure S14] had shown very few interactions with other proteins. It was the only HP interacting with another HP named Hydph20. The role of Hydph20 is unclear, but it would be interesting to understand the functions of these two HPs in the development and life cycle of P. ostreatus.

| Figure 6: (a) Protein-protein interactions of Hydph6. (b) Protein-protein interactions of Vmh2.

[Click here to view] |

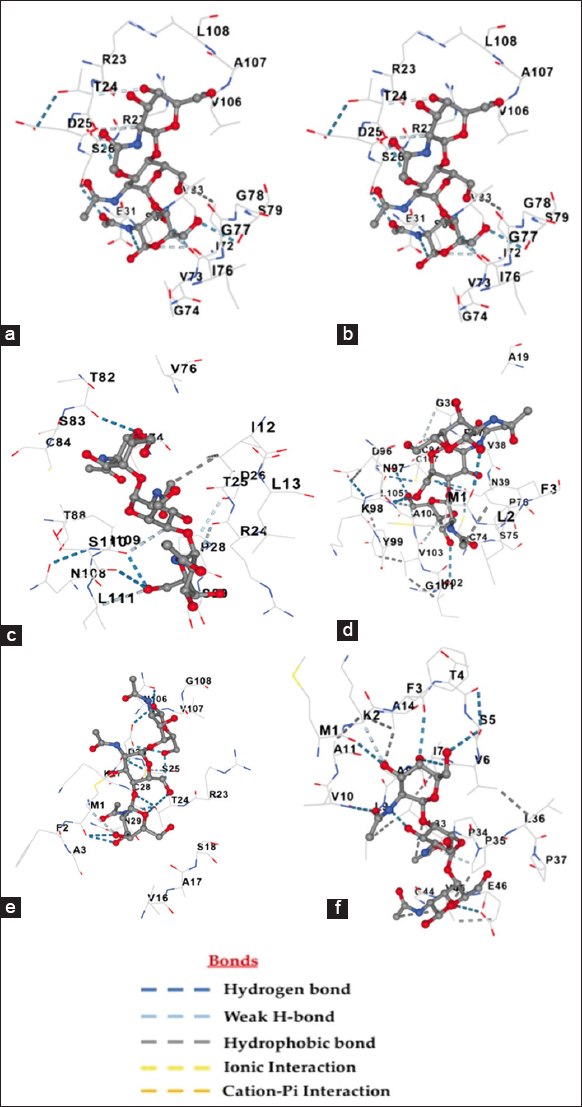

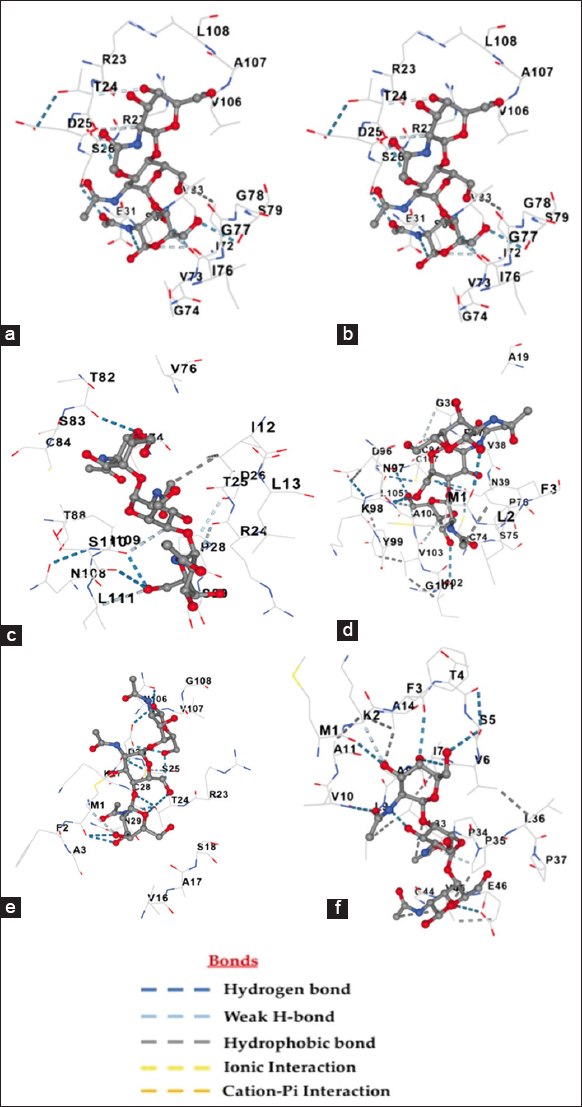

3.2.6. Molecular docking with membrane molecules

According to the docking simulations [Figure 7 (a)], Beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase, Chitinase A1 [Figure S17a], and CBP21 [Figure S17b], were chosen as a strong reference point because these molecules have a well-known interaction with chitin and a strong docking score of −7.9 Kcal/mol, −8.5 Kcal/mol, and −8.2 Kcal/mol, respectively. Out of all the HPs tested, Hydph6 had the best binding affinity with a score of −8.1 at cavity 1 [Figure 7d]. Vmh3-1 [Figure 7b] also had good results with a docking score of −7.6 at cavity 1, which was a bit lower than the benchmark but still competitive, suggesting it could be worth looking into further [17].

| Figure 7: Molecular docking modeling between chitin (ligand) and (a) beta-N Acetylglucosaminidase (control receptor); (b) Vmh3-1 hydrophobin (receptor); (c) Vmh2 hydrophobin(receptor); (d) Hydph6 hydrophobin (receptor) (e) Hydph7 hydrophobin (receptor) (f) Hydph16 hydrophobin (receptor).

[Click here to view] |

On the other hand, Vmh2, Hydph7, and Hydph16 had lower binding scores of −6.3 Kcal/mol, −6.6 Kcal/mol, and −6.7 Kcal/mol, respectively, showing they have moderate-to-limited binding abilities [Figure 7c, e and f]. Even though Hydph7 had a lot of contact residues (38), its low docking score hints at possible structural issues that might be preventing it from interacting well with chitin [Table 4]. Similarly, Hydph16’s average score could be due to structural limitations. In summary, Hydph6 is the most promising protein for interacting with chitin, followed by Vmh3-1, while the other proteins might need some structural changes to enhance their binding capabilities [17].

Table 4: Molecular Docking analysis of hydrophobins and chitin.

| Name of Protein | Ligand | Contact residues | Cavity | Score |

|---|

| Vmh2 | Chitin | 24 | C1 | −6.3 |

| Vmh3-1 | Chitin | 26 | C1 | −7.6 |

| Hydph 16 | Chitin | 40 | C4 | −6.7 |

| Hydph 7 | Chitin | 38 | C2 | −6.6 |

| Hydph 6 | Chitin | 34 | C1 | −8.1 |

| Beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase | Chitin | Chain A: 6 Chain B: 27 | C5 | −7.9 |

| Chitinase A1 | Chitin | 50 | | −8.5 |

| CBP21 (Chitin-Binding Protein 21) | Chitin | Chain A: 18 Chain B: 16 | | −8.2 |

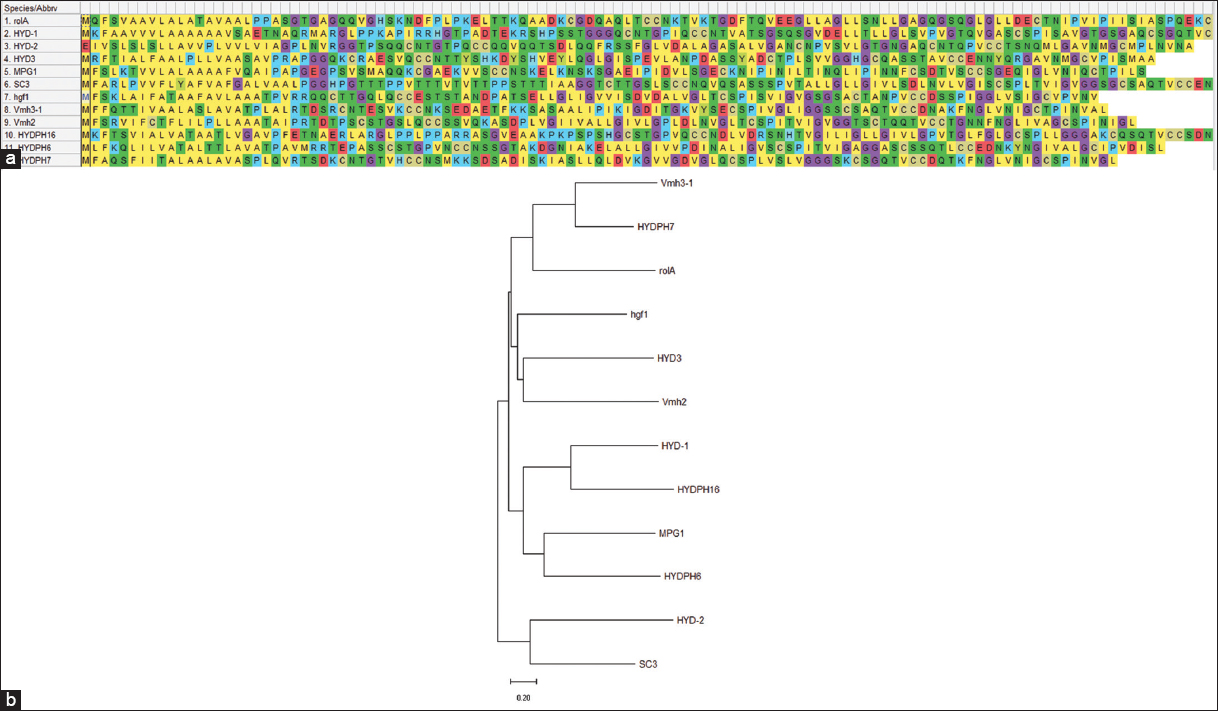

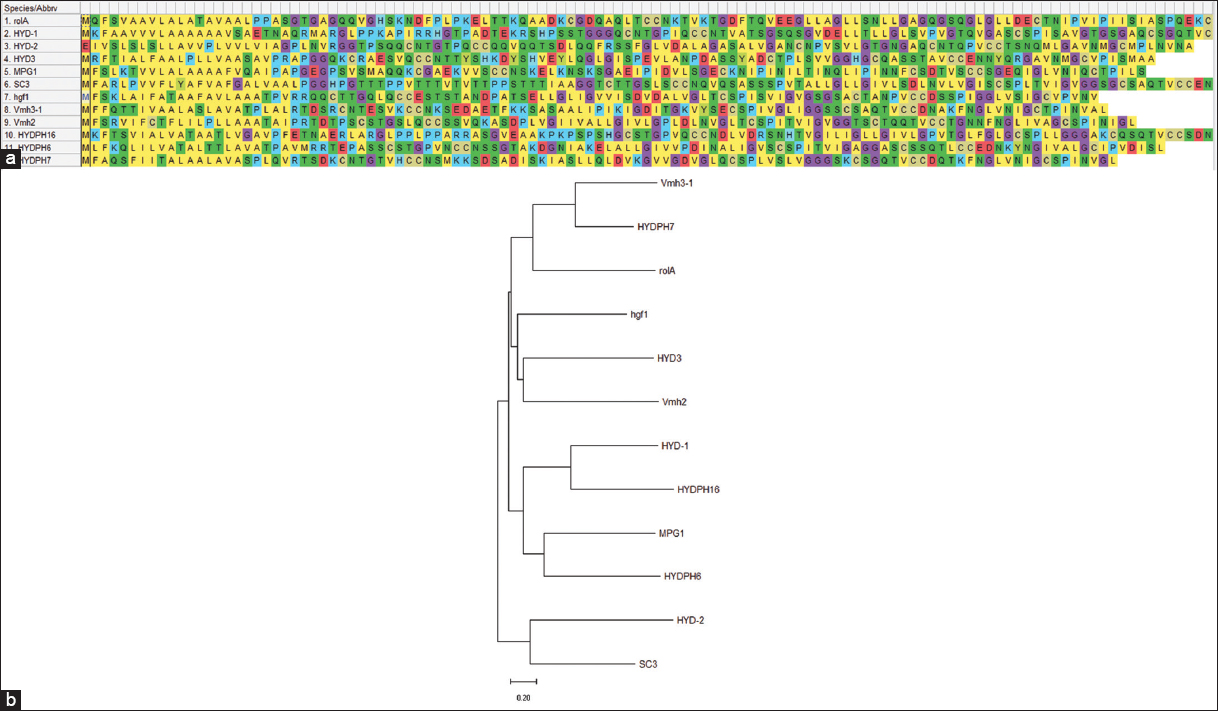

3.2.7. Evolutionary analysis

The evolutionary analysis was conducted using MEGA 11 [Figure 8]. Notably, Hydph7 and Vmh3-1 formed a closely related clade, indicating a high degree of sequence similarity and suggesting a recent common ancestor. Hydph16 clustered with HYD-1, suggesting conservation in their sequences, which could reflect comparable biological functions. Similarly, Hydph6 was grouped with MPG1, pointing toward evolutionary proximity and possible functional resemblance. Vmh2 shows association with HYD3, placing it in a separate but moderately related branch, suggesting it may possess distinct features while still sharing a common hydrophobin framework. In contrast, HYD-2 and SC3 form a more distant clade, highlighting their divergence from the primary group of interest, which may correspond to functional differences or ancestral divergence.

| Figure 8: (a) Amino acid alignment performed for HPs: Hydph6, Hydph7, Hydph16, Vmh2, and Vmh3-1. (b) Phylogenetic tree obtained after alignment of different hydrophobin sequences with Hydph6, Hydph7, Hydph16, Vmh2, and Vmh3-1.

[Click here to view] |

4. DISCUSSION

Hydrophobins are increasingly recognized for their versatility in industrial applications, ranging from biotechnology to material science. Commercially used hydrophobins such as EAS (Neurospora crassa) and SC3 have demonstrated their utility in surface modification and biosensors [25]. For instance, SC3 has been used to modify Teflon surfaces, enhancing biocompatibility, facilitating antifouling coatings, and improving bioavailability of hydrophobic drug molecules. For example, hydrophobins like SC3 have been used to formulate drugs such as nifedipine and cyclosporine A (CyA), resulting in improved bioavailability and pharmacokinetic profiles. The formulation with SC3 hydrophobin reduces peak drug concentrations, providing a more stable release over time [26]. In this study, HPs from P. ostreatus, namely Hydph6, Hydph7, Hydph16, Vmh2, and Vmh3-1, have been extracted, detected, and studied using computational tools. Orbitrap–HR-LC-MS/MS confirmed the primary sequence of these proteins, and all five HPs have been classified into the class I group of HPs.

In silico physicochemical characterization helped to determine physical and chemical parameters to study the behavior and stability of hydrophobins under several in vitro conditions [27]. Three of the five HPs (Vmh2, Hydph6, and Hydph16) were found unstable with an index value of >40. Class I hydrophobin PfH isolated from Pleurotus floridanus also showed an instability index of 49.31, suggesting instability in solution [28]. Apart from PfH, much work was not performed to study the instability index of class I HPs, but it was observed in a set of 45 class II HPs. Sixteen of 45 HPs were considered unstable as per the instability index [29], reflecting the thermostability of HPs. Studies in literature suggested that HPs are thermodynamically more stable compared to other proteins. This property was utilized to improve the thermostability of firefly luciferase and D-lactate dehydrogenase enzymes using Hydrophobin-1 (rHFB-1) [30,31]. All the selected HPs were found to be hydrophobic as per the GRAVY score. This property could be utilized in various industrial applications. Most hydrophobic HP Vmh2 has been explored for various industrial applications, like biosensor applications, as an antifouling agent, and surface modification for industrial processes [32]. It was noticeable that most of the Vmh2 applications were focusing on the modification of surfaces. HPs are membrane proteins, but in this study, the detected HPs did not show transmembrane helices. Findings in this study suggested that HPs are mostly loosely held with the membrane or secreted for different functions. This could be considered a major difference between membrane proteins and hydrophobins. GPI anchoring studies carried out suggested that all HPs were non-GPI anchored. These results were similar to the non-GPI-anchored nature of class I HPs Rod A, Rod B, and Rod C from the fungus Aspergillus fumigatus [33]. A recent study reported GPI-anchored class II HPs from fungal phytopathogens, which were responsible for the virulence and phytotoxicity of that respective fungus. It could be understood from this study that HPs are the most evolutionary developing proteins in fungi, which could alter from non-pathogenic to pathogenic as per the requirement of the native fungus in which they are expressed [2].

To explore more about the functionality of HPs, two-dimensional and three-dimensional structures were studied. According to Phyre2, HPs Hydph6, Hydph16, and Vmh2 showed a balance between alpha helices, beta sheets, and random coils contribution to the structure. They may be well-suited for applications requiring stable yet adaptable drug carriers, particularly for hydrophobic drugs. Studies done on protein as drug carriers suggested that coiled coil structures of alpha helices were more suitable for better drug release, improving drug targeting and drug uptake [34]. Vmh3-1 and Hydph7 showed higher percentages of disordered regions and beta strands. They may be more effective in surface coatings [35]. However, their stability should be carefully evaluated in specific applications. Structure prediction for all HPs was performed with a more reliable method using Modeller 9.11. The output Z-score plot from the PROSA server showed that predicted structures of Hydph6, Hydph7, Hydph16, Vmh2, and Vmh3-1 were within the range of experimentally determined structures of other HPs using NMR. Comparative analysis of the structure derived using Phyre2 and Modeller suggested that Beta sheet is the major contributor to the structure of all five HPs. In phyre2 analysis, Beta sheet structure was ranged from 23% to 31%. For each HP, Beta sheet percentage was maximum among α-helix, Beta sheet, and disordered structure. Structures derived using Modeller also showed most favored residues present in quadrant II of Ramachandran plot for all HPs, with the percentage ranging from 79.1% to 89.5%. Quadrant II denotes the most favored Beta sheet structure, and the results presented in Table 5 showed that the maximum protein backbone residues lie in this region. Structures derived using both methods suggested the presence of Beta sheets in the maximum amount in the structure of all five HPs.

Table 5: Ramachandran plot analysis of HPs from Pleurotus ostreatus.

| Hydrophobin name | HYDPH 6 plot observation | Percent composition |

|---|

| Hydph 6 | Residues in most favored region | 85.4 |

| Residues in the additional allowed region | 13.50 |

| Residues in generally allowed region | 1.0 |

| Residues in disallowed region | 0.0 |

| Hydph 7 | Residues in most favored region | 79.6 |

| Residues in additional allowed region | 18.3 |

| Residues in generally allowed region | 1.1 |

| Residues in disallowed region | 1.1 |

| Hydph 16 | Residues in most favored region | 79.6 |

| Residues in the additional allowed region | 18.3 |

| Residues in generally allowed region | 1.1 |

| Residues in disallowed region | 1.1 |

| Vmh2 | Residues in most favored region | 79.1 |

| Residues in additional allowed region | 14.3 |

| Residues in generally allowed region | 4.4 |

| Residues in disallowed region | 2.2 |

| Vmh3-1 | Residues in the most favored region | 89.5 |

| Residues in additional allowed region | 9.5 |

| Residues in generally allowed region | 0.0 |

| Residues in disallowed region | 1.1 |

Structural evaluation was followed by functional assessment of five HPs detected in this study. Out of five, Hydph6, Hydph7, and Hydph16 were first reported at the protein expression level. It was important to understand their functional roles and interaction with other proteins in P. ostreatus. Studies carried out using the STRING platform revealed very interesting interactions of HPs within the host fungal cell P. ostreatus. In previous studies, it was reported that HPs play a crucial role in the growth of the fungus [23]. An interaction study performed here supported this statement, as it was observed that Hydph6 and Vmh2 interact with Peptidase C50 domain-proteins, HORMA domain-containing proteins, and Serine/Threonine kinases. Peptidase C50 plays a role in the separation of chromosomes, cell division, and growth of the fungus. HORMA domain-containing proteins are crucial regulators of chromosome organization, while Serine/Threonine kinases are responsible for cell growth, proliferation, and cell cycle regulation. All these interactions suggested the role of HPs in cell growth. HP’s gene loci were reported to be found in the proximity of Quantitative trait loci responsible for the growth of the fungus [36]. It is evident from this study that HPs are involved in the process of cell division, which leads to cell growth. HPs Vmh3-1 and Hydph16 largely showed interactions with NPCs, which were responsible for regulated molecular trafficking of proteins, RNA, and other biomolecules. Hydph7 showed interaction with Hydph20, which would be explored in future studies to understand functional relationships between these two HPs. While the STRING database provides a useful platform for predicting potential protein–protein interactions, it is important to note its limitations. STRING integrates data from diverse sources, including computational predictions, curated database, and literature mining, which may result in false positives or indirect associations, particularly in organisms or protein families with limited experimental data. As such, the predicted interactions presented here should be interpreted with caution and serve as a starting point for future experimental validation.

Recent reported work on mutational studies of Hydph16, Vmh2, and Vmh3-1 revealed functions of HPs in the cell surface structure and growth in stressed conditions. The hydrophobicity of the cell surface was decreased due to the non-expression of Vmh2 and Vmh3 [4]. Cells devoid of Hydph16 gene expression had significantly altered cell wall formation [5]. With this background, molecular docking studies were performed with Chitin. Three chitin-interacting proteins, such as Beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase, Chitinase A1, CBP21 were selected as positive control. Chitinase A1 had shown exceptional binding with chitin (−8.5 Kcal/mol). Chitin binding protein and Beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase interacted with chitin with slightly less free energy values than Chitinase A1.

Three positive controls supported the study to understand the efficiency of binding of HPs with Chitin. Hydph6 has shown interaction with chitin with the highest free energy value of −8.1 Kcal/mol among the selected HPs. Vmh3-1 also has interaction with chitin with a moderate score. Similar in silico studies have been reported between class II hydrophobin (HFB) isolated from phytopathogenic fungi and chitin. Out of 45 experimental HFB, one HP had shown binding with chitin with a free energy (ΔG) of −7.5 Kcal/mol [28]. In comparison to this free energy value, Hydph6 had shown a strong binding energy of −8.1 Kcal/mol. Apart from in silico chitin binding of class II HFB presented by Bouqellah and Farag (2023), no reported study was available in the literature for the comparison of chitin binding intensity. Results presented by Han et al. in 2025 in mutant studies showed that genetic expression of Hydph16 was important for cell wall synthesis, especially, the chitin content of the cell wall. The current study did not highlight the interaction of Hydph16 with chitin, and better interaction was observed in Hydph6 and chitin [4]. This study is the first report to document the in silico interaction of HPs with membrane molecules to understand their roles in membrane formation. Validation of the interaction would be carried out in experimental studies to confirm the role of these HPs in membrane hydrophobicity. Mutational studies supported the interaction of Hydph16 with membrane molecules, and it was found to be responsible for membrane thickness. Although current in silico studies did not show strong chitin-Hydph16 interactions, experimental studies will be performed to validate this function.

Evolutionary studies supported their presence in the class I category and resembled other mushroom-origin HPs. This study reports the 1st time detection of Hydph6, Hydph7, and Hydph16 in mycelia of P. ostreatus. Various in silico studies performed for these proteins provided information about structural and functional characteristics. Considering limitations of in silico studies to fully account for the complex, flexible, and dynamic nature of the proteins with respect to their conformational changes and behavior in solutions, experimental work should be performed [37]. To support a complete understanding of the function of these proteins, experimental validation would be of great help. In future studies, recombinant production of these proteins, functional assays to understand protein–protein interaction, and chitin interaction with proteins would be carried out. These experiments would really help to identify industrially important HPs under this study. Future scope of the study also includes the development of industrial applications of Hydph6 and Hydph7. Mutational studies are also important to understand the physiological roles of these hydrophobins.

5. CONCLUSION

In silico characterization of Hydph6, Hydph7, Hydph16, Vmh2, and Vmh3-1 helped to understand the major properties of all HPs. Vmh2 was found to be the most hydrophobic, thermostable, and moderately stable HP having a balanced alpha helices, beta sheets, and random coils. Interaction studies showed the importance of Vmh2 and Vmh3-1, with maximum interaction with different proteins. This could help to justify the expression of Vmh3-1 at each developmental stage of P. ostreatus. Hydph6 and Vmh3-1 showed high affinity for chitin, an important membrane molecule. In summary, computational analysis of all these HPs underlined characteristics important for industrial applications. Vmh3-1 showed moderate properties with abundance in interaction and presence in the species at various growth phases. Hydph7 came up with promising moderate hydrophobicity, stability, thermotolerance, and interaction with Hydph20, suggesting some special role. Future scope of the study includes working on the production and purification of Hydph6 and Hydph7 and validation of characteristics observed in computational studies. Considering the class I nature of these HPs, surface modification applications will be explored, such as the development of antifouling agent, design of drug delivery system, and design of effective biosensors.

7. AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All the authors are eligible to be an author as per the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) requirements/guidelines.

8. ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are thankful to affiliated institutions for providing the requisite facilities.

9. FUNDING

There is no funding for this work.

10. CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no competing financial or any other conflicts of interest in this work.

11. ETHICAL APPROVALS

This study does not involve experiments on animals or human subjects.

12. DATA AVAILABILITY

All the data are available with the authors and shall be provided on request.

13. PUBLISHER’S NOTE

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. This journal remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliation.

14. USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (AI)-ASSISTED TECHNOLOGY

The authors declare that they have not used artificial intelligence (AI) tools for writing and editing the manuscript, and no images were manipulated using AI.

REFERENCES

1. Wösten HAB, De Vocht ML. Hydrophobins, the fungal coat unravelled. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Biomembr. 2000;1469(2):79-86.[CrossRef]

2. Whiteford JR, Spanu PD. Hydrophobins and the interactions between fungi and plants. Mol Plant Pathol. 2002;3(5):391-400.[CrossRef]

3. Wu Y, Li J, Yang H, Shin HJ. Fungal and mushroom hydrophobins:A review. J Mushroom. 2017;15(1):1-7.[CrossRef]

4. Han J, Kawauchi M, Terauchi Y, Tsuji K, Yoshimi A, Tanaka C, et al. Physiological function of hydrophobin Hydph16 in cell wall formation in agaricomycete Pleurotus ostreatus. Fungal Genet Biol. 2025;176:103943.[CrossRef]

5. Han J, Kawauchi M, Schiphof K, Terauchi Y, Yoshimi A, Tanaka C, et al. Features of disruption mutants of genes encoding for hydrophobin Vmh2 and Vmh3 in mycelial formation and resistance to environmental stress in Pleurotus ostreatus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2023;370:fnad036.[CrossRef]

6. Xu D, Wang Y, Keerio AA, Ma A. Identification of hydrophobin genes and their physiological functions related to growth and development in Pleurotus ostreatus. Microbiol Res. 2021;247:126723.[CrossRef]

7. Peñas MM, Rust B, Larraya LM, Ramírez L, Pisabarro AG. Differentially regulated, vegetative-mycelium-specific hydrophobins of the edible basidiomycete Pleurotus ostreatus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68(8):3891-8.[CrossRef]

8. Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227(5259):680-5.[CrossRef]

9. Kyte J, Doolittle RF. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157(1):105-32.[CrossRef]

10. Kelley LA, Sternberg MJE. Protein structure prediction on the web:A case study using the Phyre server. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(3):363-73.[CrossRef]

11. Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST:A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389-3402.[CrossRef]

12. Shehadi IA, Rashdan HRM, Abdelmonsef AH. Homology modeling and virtual screening studies of antigen MLAA-42 protein:Identification of novel drug candidates against leukemia-an in silico approach. Comput Math Methods Med. 2020;2020:8196147.[CrossRef]

13. Shi J, Blundell TL, Mizuguchi K. FUGUE:Sequence-structure homology recognition using environment-specific substitution tables and structure-dependent gap penalties. J Mol Biol. 2001;310(1):243-57.[CrossRef]

14. Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W:Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(22):4673-80.[CrossRef]

15. Webb B, Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling using MODELLER. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2016;54:5.6.1-37.[CrossRef]

16. Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK:A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26(2):283-91.[CrossRef]

17. Liu Y, Yang X, Gan J, Chen S, Xiao ZX, Cao Y. CB-Dock2:Improved protein-ligand blind docking by integrating cavity detection, docking and homologous template fitting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(W1):W159-64.[CrossRef]

18. Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina:Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31(2):455-61.[CrossRef]

19. Armenante A, Longobardi S, Rea I, De Stefano L, Giocondo M, Silipo A, et al. The Pleurotus ostreatus hydrophobin Vmh2 and its interaction with glucans. Glycobiology. 2010;20(5):594-602.[CrossRef]

20. Kulkarni SS, Nene SN, Joshi KS. Identification and characterization of a hydrophobin Vmh3 from Pleurotus ostreatus. Protein Expr Purif. 2022;195-6:106095.[CrossRef]

21. Nakazawa T, Kawauchi M, Otsuka Y, Han J, Koshi D, Schiphof K, et al. Pleurotus ostreatus as a model mushroom in genetics, cell biology, and material sciences. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2024;108(1):1-21.[CrossRef]

22. De Vocht ML, Reviakine I, Ulrich WP, Bergsma-Schutter W, Wösten HAB, Vogel H, et al. Self-assembly of the hydrophobin SC3 proceeds via two structural intermediates. Protein Sci. 2002;11(5):1199.[CrossRef]

23. Bayry J, Aimanianda V, Guijarro JI, Sunde M, LatgéJP. Hydrophobins-unique fungal proteins. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(5):1002700.[CrossRef]

24. Meister K, Bäumer A, Szilvay GR, Paananen A, Bakker HJ. Self-assembly and conformational changes of hydrophobin classes at the air-water interface. J Phys Chem Lett. 2016;7(20):4067-71.[CrossRef]

25. Rojas-Osnaya J, Quintana-Quirino M, Espinosa-Valencia A, Bravo AL, Nájera H. Hydrophobins:Multitask proteins. Front Phys. 2024;12:1393340.[CrossRef]

26. Salve AL, Apotikar SB, Muddebihalkar SV, Joshi KS, Kulkarni SS. Applications of hydrophobins in medical biotechnology. J Sci Res. 2022;66(3):86-94.[CrossRef]

27. Guruprasad K, Reddy BVB, Pandit MW. Correlation between stability of a protein and its dipeptide composition:A novel approach for predicting in vivo stability of a protein from its primary sequence. Protein Eng. 1990;4(2):155-61.[CrossRef]

28. Rafeeq CM, Vaishnav AB, Manzur Ali PP. Characterisation and comparative analysis of hydrophobin isolated from Pleurotus floridanus (PfH). Protein Express Purif. 2021;182:105834.[CrossRef]

29. Bouqellah NA, Farag PF. In silico evaluation, phylogenetic analysis, and structural modeling of the class II hydrophobin family from different fungal phytopathogens. Microorganisms. 2023;11(11):2632.[CrossRef]

30. Mokhtari-Abpangoui M, Lohrasbi-Nejad A, Zolala J, Torkzadeh-Mahani M, Ghanbari S. Improvement thermal stability of d-lactate dehydrogenase by hydrophobin-1 and in silico prediction of protein-protein interactions. Mol Biotechnol. 2021;63(10):919-32.[CrossRef]

31. Lohrasbi-Nejad A, Torkzadeh-Mahani M, Hosseinkhani S. Hydrophobin-1 promotes thermostability of firefly luciferase. FEBS J. 2016;283(13):2494-507.[CrossRef]

32. Piscitelli A, Pennacchio A, Longobardi S, Velotta R, Giardina P. Vmh2 hydrophobin as a tool for the development of “self-immobilizing“enzymes for biosensing. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2017;114(1):46-52.[CrossRef]

33. Valsecchi I, Dupres V, Stephen-Victor E, Guijarro JI, Gibbons J, Beau R, et al. Role of Hydrophobins in Aspergillus fumigatus. J Fungi. 2018;4(1):2.[CrossRef]

34. Utterström J, Naeimipour S, Selegård R, Aili D. Coiled coil-based therapeutics and drug delivery systems. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;170:26-43.[CrossRef]

35. Janssen MI, Van Leeuwen MBM, Van Kooten TG, De Vries J, Dijkhuizen L, Wösten HAB. Promotion of fibroblast activity by coating with hydrophobins in the b-sheet end state. Biomaterials. 2004;25(14):2731-9.[CrossRef]

36. Larraya LM, Idareta E, Arana D, Ritter E, Pisabarro AG, Ramírez L. Quantitative trait loci controlling vegetative growth rate in the edible basidiomycete Pleurotus ostreatus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68(3):1109-14.[CrossRef]

37. Gupta CL, Akhtar S, Bajpai P. In silico protein modeling:Possibilities and limitations. EXCLI J. 2014;13:513-5.