1. INTRODUCTION

The use of bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria (LAB) strains has several advantages over traditional antibiotics. In particular, the production of recombinant forms of the peptide, its potential for application in both the food and clinical industries, its high efficiency, and its relative lack of toxicity to eukaryotic cells have made these peptides very interesting and promising candidates for combating pathogenic strains [1-3]. Klaenhammer initially divided them into four classes: (I) lantibiotics – small molecules containing post-translationally modified peptides, lanthionine and β-methyllanthionine (e.g., nisin); (II) unmodified, small and thermostable peptides (e.g., pediocin); (III) large, thermolabile bacteriocins (helveticin and colicin); and (IV) complex bacteriocins linked to glycols or lipoproteins.

The Class IIa pediocin-like bacteriocins are considered among the most promising candidates for use as potential bioconservants in the food industry due to their strong anti-Listeria activity, which is associated with their common YGNGV motif at the N-terminus of the peptide [4,5]. In recent years, various researchers have reported a number of Class IIa bacteriocins from LAB strains, such as plantaricin LPL-1 [6], GA15 [7], SR18 [8], plantaricin 423 [9], plantaricin C19 [10], plantaricin IIA-1A5 [11], plantaricin LD1 [12], and BM1029; however, only one commercial product, nisin, is currently registered on the market [13]. In food preservation, more and more bacteriocins have been tested as natural antimicrobial agents due to their potent antibacterial properties [14]. Bacteriocins inhibit the growth of many foodborne pathogens and spoilage bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus [15], Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas spp., Bacillus spp., and Clostridium spp. They can also be used in various food products to increase shelf life [16]. Another important aspect of this group of bacteriocins is their resistance to high temperatures and pressures. The low molecular weight of the proteins and the presence of disulfide (S-S) bonds are significant factors for their temperature resistance (heat stability). For example, the above-mentioned LD-1 plantaricin and LPL-1 [6], which have a molecular weight of up to 7 kDa, are both thermoresistant at 100°C and 121°C, while the IIA-1A5 peptide, which has a molecular weight of 9.5 kDa, is thermoresistant at 60–80°C [11]. Thus, the identification of potential LAB strains producing bacteriocins [17], as well as the identification and characterization of bacteriocins that meet the needs of the market, is still significant.

In addition, purified bacteriocin was partially characterized for use in the food industry as a food preservative. In recent years, special attention has been given to isolating and characterizing new bacteriocin-producing strains [18,19]. The purpose of this study was to screen and identify a powerful strain of LAB, as well as a bacteriocin. In the present work, an antimicrobial bacteriocin produced by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum K-2 was purified and its primary characterization was performed.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Culture Conditions, Growth, and Isolation of Bacteria

Traditional homemade fermented cabbage was sliced and added to a saline solution, and 10 μL of the sample was inoculated into dishes with MRS agar medium (HiMedia, India) using a cup distribution technique. The Petri dishes were incubated at 37°C for 24 h, following the identification of bacteria. All indicator strains were cultured in Mueller–Hinton broth at 37°C and stored at −80°C in Mueller–Hinton medium (HiMedia, India) supplemented with 25% (vol./vol.) glycerol.

2.2. Screening of Bacteriocin-producing Strains of LAB

In this work, only those with high antimicrobial activity were selected from more than 110 previously studied Lactobacillus isolates. The highly active lactobacillus isolate was inoculated into 5 mL of MRS broth and cultured under anaerobic conditions at 37°C for 24 h. The cell-free supernatant was obtained by culture centrifugation at 7000 ×g for 20 min at 4°C and subjected to a test for antimicrobial activity by diffusion into agar wells after bringing the pH of the supernatant to 6.8 ± 0.2 using 1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH). L. monocytogenes ATCC 1911 was used as an indicator strain, and trypsin or proteinase K was applied only on one side of the wells to ensure that the antimicrobial activity was due to the substances in the protein. The antibacterial activity of the isolates was evaluated by measuring the diameters of the inhibition zones. Bacteriocin-producing isolates with relatively high antibacterial activity were selected for subsequent studies.

2.3. Identification of the L. plantarum K-2 Strain

Identification of potential strains of LAB-producing bacteriocin was carried out in accordance with their cellular morphology, physiological characteristics, carbohydrate fermentation models, and Gram staining properties. The most active bacteriocin-producing strains, including L. plantarum K-2, were additionally identified by 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequencing using the following universal PCR primers: 16S rRNA–F: BAC27f–GAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG and 16 rRNA–R: BAC1492r–GGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT [20]. The results of 16S rRNA sequencing were aligned against NCBI database, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA X software.

2.4. Growth Dynamics and Plantaricin Production

The L. plantarum K-2 strain was cultured in 10 mL of MRS broth to an OD600 = 2.0. Then inoculated in 1 L of MRS broth (pH 6.5) at 0.5% (vol./vol.) of the inoculate for 72 h at 37°C without stirring. Samples were taken every 6 h and cell density (OD600), pH, and antimicrobial activity were assessed. Antimicrobial activity was calculated as activity units (AU/mL) using the dilution method. Furthermore, the activity of crude plantaricin K-2 against L. monocytogenes ATCC 1911 was tested using the spot-on-lawn agar method and the inhibition zones (mm) were measured.

2.5. The Process of Purification of Plantaricin K-2

L. plantarum K-2 was statically cultured in 1 L of MRS broth (HiMedia, India) for 48 h at 37°C by inoculation of 0.5% (vol./vol.) pure culture. After incubation, the culture was centrifuged at 7000 × g for 20 min at 4°C to pellet the bacterial cells. The resulting cell-free culture supernatant (CFC) was collected, and its pH was adjusted to 6.5, and the culture supernatant was incubated at +80°C for 15 min to inactivate proteases and avoid possible contamination.

2.5.1. Sequential purification of active fractions

For initial purification, the CFC was diluted 2 times using 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.5) and applied to a pre-equilibrated SP-Sephadex C-25 cation-exchange column (20 mL; GE Healthcare, Sweden) equilibrated with the same buffer. The column was washed with two column volumes of 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.5), and proteins were eluted stepwise using increasing concentrations of sodium chloride (NaCl) (0.1, 0.3, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0 M) in 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Eluted fractions were collected and assessed for antibacterial activity against the designated indicator strain. Active fractions were pooled and subjected to further purification.

Secondary purification was performed using a Sep-Pak C18 cartridge (0.5 × 2.5 cm; Waters, USA), pre-equilibrated with 1 M NaCl in 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.5). Bound proteins were eluted using stepwise concentrations of acetonitrile (5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, 30%, 40%, 60%, and 80%) in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). Each fraction was dried, reconstituted in sterile distilled water, and again tested for antibacterial activity.

Finally, the active fraction from the Sep-Pak C18 purification was subjected to high-resolution purification using reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC). The sample was loaded onto a Zorbax 300SB-C18 column (5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm; Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) and eluted using a linear gradient of acetonitrile (in 0.1% TFA) from 0% to 80% over 35 min at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. Elution was monitored at 280 nm, and all collected fractions were screened for antibacterial activity against the indicator strain. Antibacterial activity was quantified in arbitrary units per milliliter of culture medium (AU/mL), where one AU was defined as the reciprocal of the highest two-fold dilution (in 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.5) that produced a clear inhibition zone against the indicator strain. The protein concentration in each purification step was determined using the Lowry method [21]. Based on these results, key parameters, including specific activity and recovery rate, were calculated for each purification stage.

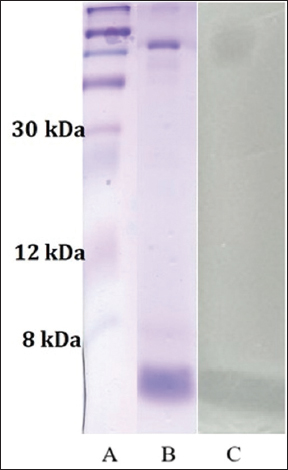

2.6. Determination of the Molecular Weight and Analysis of Plantaricin K-2 by Agar

Molecular weight determination was carried out in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) electrophoresis. A 15% separating gel was prepared accordingly. The gel was stained with diamond blue Coomassie R-250 to determine the size of the molecule, and washed for 60 min with a triple change of distilled water. Then, 25 mL of a soft agar medium inoculated with an indicator strain was applied after removing the water and incubated for 18–24 h to match the molecular weight and antibacterial activity. The molecular weight of plantaricin K-2 was determined by time-of-flight mass spectrometry as described in our previous work [2].

2.7. Antimicrobial Spectrum of L. plantarum K-2 and Plantaricin K-2

The spectrum of antimicrobial action against dozens of clinical and reference Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains and some strains of fungi for both L. plantarum K-2 and plantaricin K-2 (samples of 90 micrograms/mL from hydrophobic interaction chromatography) was tested using agar spot analysis. 5 μL of L. plantarum K-2 cells grown overnight in 10 mL of MRS broth (HiMedia, India) were applied to MRS agar, and after incubation at 37°C for 48 h, the cells were killed using chloroform vapors for 30 min, and an aliquot of indicator strains(~106-8 CFU/mL) incubated in Mueller–Hinton agar broth for 24 h at 37°C was placed on a spot with 5 mL of semi-solid agar. Similarly, 10 μL of partially purified plantaricin K-2 (90 μg/mL) was applied to MRS agar and subjected to antimicrobial activity against the same indicator strains by point analysis, as described above.

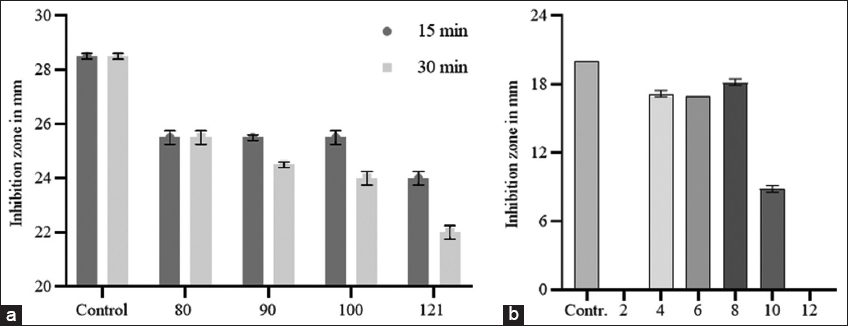

2.8. Effect of Proteases, Temperature, pH, and Ethanol on the Activity of Plantaricin K-2

10 μL of pepsin (3,200-4,500 units/mg protein, Sigma-Aldrich, USA), trypsin (10,000 BAEE units/mg protein, Sigma-Aldrich, USA), α-chymotrypsin (≥40 units/mg protein, Sigma-Aldrich), papain (≥10 units/mg, Sigma-Aldrich, USA), and proteinase K (≥30 units/mg protein, Sigma-Aldrich USA) at 1 mg/mL doses were separately added to 100 μL of the active samples obtained by RP-HPLC and incubated at 37°C for 4 h. Samples treated with the same amount of 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.5) were used as a positive control. To determine the thermal stability of plantaricin K-2, partially purified samples from hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HIC) (90 μL/mL) were exposed to temperatures of 80°C, 90°C, and 100°C for 15 and 30 min in a thermostatic water bath and in an autoclave at 121°C for 15 min, and unincubated samples were used as a control. Solutions of partially purified bacteriocin with a pH ranging from 2 to 12 were separately prepared to test the pH stability using hydrogen chloride or NaOH and incubated at 37°C for 4 h. The pH of all the samples was adjusted to 6.5, and the samples were diluted until all the samples reached the same concentration (2.5 μL/mL) before analysis for antimicrobial activity. The samples were not subjected to pH changes but were at the concentration used as a positive control. To test the effect of ethanol, various concentrations of ethanol (5, 10, 15, 20, and 25%) were prepared in bacteriocins by adding 96% ethyl alcohol. Positive and negative samples were prepared by adding a proportional amount of sterile distilled water to aliquots of bacteriocin or ethanol to sterile distilled water, respectively. All samples were analyzed for their antimicrobial activity against the indicator strain by diffusion in agar wells, and the results are presented in mm transparent inhibition zones.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3) and repeated at least 3 times independently to ensure reproducibility. The results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses and graphical representations were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 9.5.1).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Screening of Bacteriocin-forming Strains of LAB

In this work, we demonstrated that a strain of L. plantarum isolated from fermented cabbage exhibited relatively high antimicrobial activity against several indicator strains, including L. monocytogenes ATCC 1911 and S. aureus strains. However, L. plantarum K-2 strain isolated from home-fermented cabbage showed greater antimicrobial activity against L. monocytogenes ATCC 1911 than the other strains and was therefore selected as the target strain for further characterization [Table 1].

Table 1: Antimicrobial activity of L. plantarum strain K-2 and plantaricin K-2.

| Indicator strain | L. plantarum K-2 straina | Plantaricin K-2b | Antibiotic resistancec |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive bacteria | |||

| Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 1911 | 20±0.05 | 25 | - |

| Staphylococcus aureus D-5 | 20±0 | 22 | OFX, C, CRO, LVX, DOC, AM |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29923 | 32±0.5 | - | OX |

| Staphylococcus aureus D-2 | 20±0.28 | 8 | OFX, CIP, C, FOS |

| Staphylococcus aureus 0359446/wood | 25±0.25 | 21 | PO, K |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis D-3 | 0 | - | PO, CLR, TET, CO |

| Bacillus subtilis 5 | 16±0.47 | - | - |

| Gram-negative bacteria | |||

| Proteus mirabilis CAT-0103 | 35±0.25 | - | PO, CLR, TET, OX |

| Proteus morganii 399 | 20±0.25 | 16 | PO, CLR, OX |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae B-1823 | 10±0 | - | ST, CE, PIP, OX |

| E. coli 477 | 28±0.25 | - | OX |

| E. coli CAT-0200 | 20±0.28 | 10 | - |

| P. aeruginosa 003841/114 | 32±0.5 | 17 | PO, CLR, OX |

| P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | 18±0.5 | - | OX |

| P. aeruginosa D-1 | 28±0.5 | - | TET, CO |

| P. aeruginosa D-2 | 26±0.5 | - | OFX, PO, CLR, C, AN |

| Serratia marcescens 367 | 20±0.25 | - | PO, OX |

| Enterococcus faecalis CAT-0203 | 25±0.25 | 12 | OX |

| Fungi | |||

| Candida albicans CAT-0204 | - | - | |

| Candida tropicalis CAT-02041 | - | 20 | PO, K, ST, CE, CLR, CO, AN |

Legend: aThe values represent the diameter of the inhibition zone (mm) measured by the agar spot lawn diffusion assay. Data are presented as mean±standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments. bThe activity of plantaricin was tested by the agar spot lawn method, and the results were recorded. cAN: Amikacin; RI: Rifampicin; OFX: Ofloxacin; PO: Polymyxin; K: Kanamycin; ST: Streptomycin; CE: Cefotaxime; CLR: Clarithromycin; CIP: Ciprofloxacin; TET: Tetracycline; CO: Co-trimoxazole; C: Chloramphenicol; PIP: Piperacillin; OX: Oxacillin; CRO: Ceftriaxone; LVX: Levofloxacin; DOC: Doxycycline; AM: Ampicillin; FOS: Fosfomycin.

3.2. Identification of the L. plantarum K-2 Strain

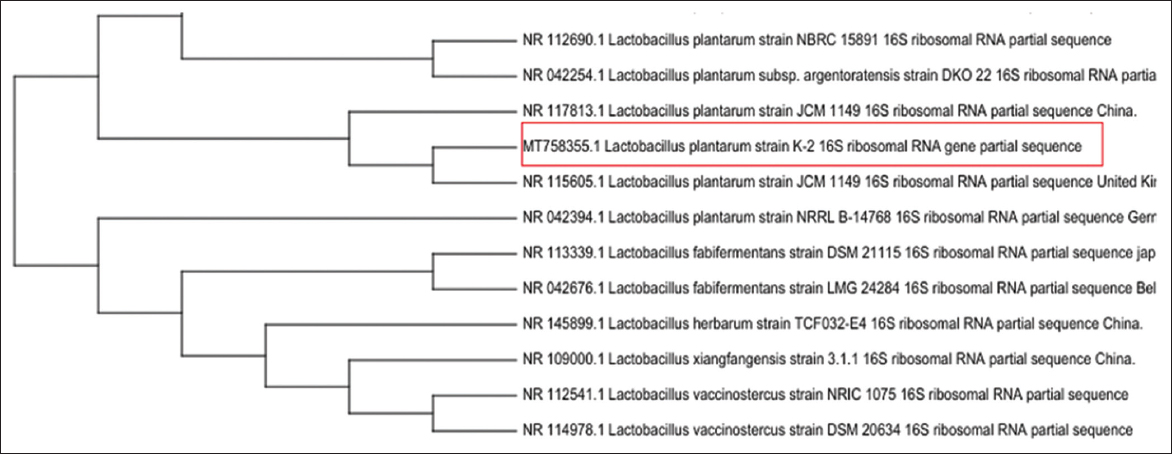

The stained cells of LAB had the shape of a rod, without spores, when examined under a microscope, and were also determined to be Gram-positive. Other characteristics, including the nature of carbohydrate fermentation (data not shown here), suggested that the strain belongs to the genus L. plantarum species. L. plantarum K-2 16S rRNA gene amplified using universal primers and the nucleotides were sequenced. The resulting 16S rRNA nucleotide sequence was compared with that in the NCBI reference database using BLAST algorithms, and the 16S rRNA sequence of L. plantarum showed 99% similarity. Our isolate highlighted in red is MT753855.1 (L. plantarum strain K-2), which is located in the same group as other L. plantarum strains, in particular JCM 1149 (China and Great Britain).The upper cluster of the tree shows strains related to the L. plantarum species, while the lower branches contain representatives of Lactobacillus fabifermentans, L. herbarium, L. xiangfangensis, and other species. The results of this phylogenetic analysis indicate that our isolate has a close genetic relationship to the L. plantarum species. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the algorithm of combining neighbors in the MegaX program [Figure 1]. The obtained results confirm the molecular identification of the isolate and scientifically substantiate its inclusion in the L. plantarum group.

| Figure 1: Phylogenetic tree of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene of lactic acid bacteria. [Click here to view] |

3.3. Growth Dynamics and Production of Plantaricin K-2

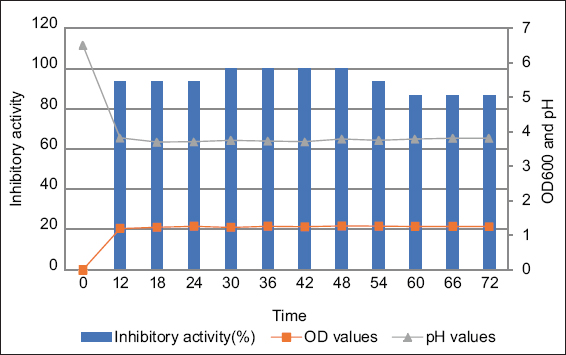

The growth dynamics of L. plantarum K-2 showed that the strain entered the stationary phase after 12 h of incubation, with culture density remaining relatively stable from 12 to 72 h [Figure 2]. Similarly, the pH of the culture medium decreased sharply from 6.5 to 3.65 within the first 12 h, followed by only slight changes throughout the remainder of the incubation period, reaching a final value of approximately 3.5.

| Figure 2: Dynamics of the Lactiplantibacillus plantarum bacterial growth and formation of plantaricin K-2. Blue columns stand for inhibitory activity; orange circles mean OD values and grey circles show the pH values. [Click here to view] |

Maximum inhibitory activity was observed between 30 and 48 h, during which the largest inhibition zones and the highest activity (up to 6400 AU/mL) were recorded. After 54 h, a clear decline in activity was noted, likely due to bacteriocin degradation, instability, or reduced production in the later stages of growth. These findings suggest that optimal bacteriocin production by L. plantarum K-2 occurs between 30 and 48 h of incubation, corresponding to the early stationary phase of growth.