1. INTRODUCTION

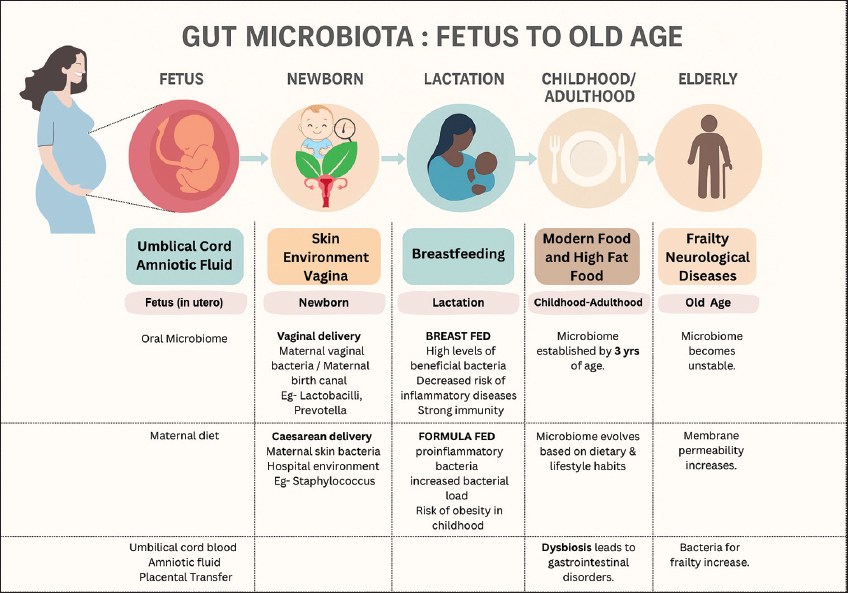

The term gut, synonymous with gastrointestinal tract (GIT) is a passageway of an elaborate digestive system. It is the largest reservoir of microbes in the human body. Leading from the mouth and ending in the anus, the entire GIT comprises organs such as the stomach, liver, gall bladder, and pancreas, along with their secretions. The gut microflorae along with their DNA and the surrounding milieu in which these microbes reside, are referred to as the gut microbiome and, occasionally considered as a virtual organ of the body [1]. This gut microflorae with over 100 trillion microbes, includes the commensals and pathobionts and bacteria, viruses, and fungi that weigh around 200 g [2]. The organs along the GIT together perform intricate processes of mechanical and chemical digestion and absorption of digested food. It is also assigned the function of subsequent elimination of undigested food. The walls of the GIT are supplied with neurons, forming the enteric nervous system (ENS) very similar to the central nervous system (CNS). The gut, also referred to as the “second brain” has a significant function in the mental health of an individual. The microbes help in establishing a communication between the brain and the gut which is responsible for the neurological and immunological health of an individual [3]. However, it is the intestine that harbors the most diverse and abundant microbial community in the body [4]. This microbial population is dominant in bacteria that are from categories such as the Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria [5]. Intestinal bacterial phyla are represented by Firmicutes (species, e.g., Clostridiales, Lactobacillus, Enterococcus) and Bacteroidetes (species, e.g., Bacteroides) that make up the larger proportion while the other phyla Actinobacteria (Bifidobacteria), Proteobacteria (Escherichia coli), Fusobacteria, and Verrucomicrobiota are represented in less numbers [6,7]. Bifidobacterium is a beneficial bacterium that helps to fight harmful bacteria [8]. It also helps in receiving the energy from diet in the adipose tissues, hence protecting the individual from diet-related obesity [9].

A decline in the diversity of microbes or loss of beneficial microbes leads to dysbiosis, a condition that makes an individual susceptible to various immune-mediated, metabolic, neural, and psychiatric diseases. A dysbiotic microbiota can further alter the barrier integrity and flood the tissues and organs with molecules/microbes/toxins, which negatively impact the metabolism. Since the gut microbes set an individual’s metabolism, immunity, and overall health trajectory [10], it is imperative to know the communication between the microbiome and the body parameters. Investigations on gut microbial diversity are therefore, an emerging technology that facilitates insights into microbial ecosystems. The 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) amplification and whole-genome shotgun sequencing are the two most commonly used methods to study the diversity of the gut microbiota [11]. Lack of microflora diversity in the gut leads to various medical conditions, such as the gastroesophageal reflux or peptic ulcer diseases. This further involves treatments such as proton pump inhibitors and comprehensive digestive stool analysis. Moreover, it is evident that dietary-based modifications in the gut microbiome are the safest way to achieve a healthy self. Hence, the function of pre- and probiotics in the diet cannot be overlooked.

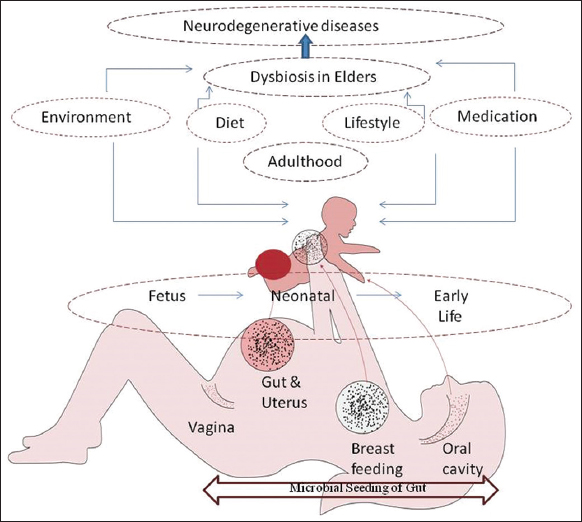

The present review provides a brief about the crucial role played by the gut microflora and the biological interactions within the body. It also reiterates the importance of a healthy lifestyle and diet in maintaining a balance of our gut microbiome. The state of imbalance or dysbiosis leads to health complications and therapeutic interventions. Further, the review also suggests some uncomplicated microbiome restoration strategies, thereby opening new avenues for preventive healthcare [Figure 1].

2. GUT MICROBIOME – THE SIGNATURE OF LONGEVITY

The diverse microbiome, besides microbes, also includes 50–100 fold more genes in the host. These additional genes contribute enzymes, not coded by the host. These enzymes play a crucial role in modulating host metabolism and hence are a significant part in the regulation of host physiology [12]. Certain bacteria, such as Bacteroides fragilis, Eubacterium lentum, Enterobacter agglomerans, Serratia marcescens, and Enterococcus faecium [13], anaerobically synthesize vitamin K2 (menaquinone) that is essential in decreasing vascular calcification, elevating high-density lipoprotein, and lowering cholesterol. All these are also significant in lowering the risk of cardiovascular disorders [14]. Gut bacteria also synthesize Vitamin B and Vitamin K, which have an important role in sugar and fat metabolism and maintenance of hemostatic functions. Further, the deficiency of Vitamin B5 and Vitamin B12, linked to disorders such as insomnia, neuropsychological disorders is regulated by the gut microbes [15,16].

Gut microflora is known for its function in the co-metabolism of bile acids with the host where they get associated with the liver to help detoxify and get rid of xenobiotics [17]. Furthermore, cholesterol-derived chemicals that are synthesized in the liver, conjugate with glycine or taurine, are subsequently stored in the gall bladder and then secreted in the duodenum where the digestive process is aided. About 95% of bile acids get reabsorbed at the distal ileum, and the remaining 5%, which are the unabsorbed primary bile acids, are bioconverted to secondary bile acids, deoxycholic acid, and lithocholic acid. The enzymes required for this conversion are provided by the colon bacteria such as Clostridium scindens [18]. Thus, these bacteria prove to regulate certain digestive conditions through the levels and bile acid profiles [19].

Microbes synthesize metabolites with pleiotropic effects. These metabolites further act as signaling molecules facilitating neuroendocrine crosstalks. This function physiologically links the gut with other systems. The gut and the central nervous system communicate through the vagus nerve that arises in the cranium. The gut microbiota establishes a connection with various pathways and metabolic processes such as the digestive, immune, and blood barrier systems. If the microbial diversity and/or population is disturbed, this communication falls apart. Leaky gut barrier is one of the reasons, another being dysbiosis which leads to low-grade systemic inflammation adversely affecting multiple organs [20]. The Gut–Brain Axis (GBA) is known for a significant role in diseases prevalent in elderly people, such as Alzheimer’s, an old age-related disease. The neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, noradrenaline, and gamma-aminobutyric acid required for GBA communication are synthesized partly in specialized epithelial cells (enteroendocrine cells) of the gut. These cells are, in turn, influenced by the gut microflora [21,22]. The microbiota can directly synthesize neurotransmitters and influence the enzymes and transporters involved in neurotransmitter metabolism. Besides the neurotransmitters, there are other regulatory mechanisms in the communication that occur in the gut. While the vagus nerve strikes a direct connection, the gut environment is further sensed by the ENS. The signals sent by the ENS are transmitted to the brain which then controls the cognitive functions. The Gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) with its immune system also assists in recognizing the signals given by the microbiota by releasing signaling molecules such as cytokines. These molecules cross blood–brain barrier along with the short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) which actuate the release of hormones from the gut and are then carried to the brain.

3. GUT BARRIER - INTEGRITY AND DYSBIOSIS

The gut barrier or the mucosal barrier comprises a mucus layer and epithelium and is a link between the outside surroundings and the host internal milieu for the microbes. The gut microbiota such as E. coli, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Clostridium perfringens and several such species of the internal milieu and the host immune cells (external host environment) such as macrophages and neutrophils occupy different “niche” in the intestine. The latter are genetically tuned to attack invading alien organisms. As a result, the gut microbes can also be destroyed by host immune cells if they enter the external environment. It happens when the mucosal barrier is impaired. The leaky gut allows the microbes from the internal milieu to enter the mucosa with ease which are further attacked by the “resident” macrophages. This excessive immune response to gut microbes induces intestinal inflammation, the very cause of several gastrointestinal diseases [23].

The inflammation and dietary habits of an individual are intricately related to gut microbial imbalance and disease occurrence. Although majorly diet is known for maintaining beneficial microbe balance in the gut, the reverse cycle may also be true. Inflammation of the gut can also induce microbial imbalance or dysbiosis, leading to a pathological state. The diet rich in sugars and fats accelerates loss of intestinal membrane integrity leading to inflammation. In the reverse order dysbiosis and inflammation disrupt membrane integrity, which allows bacterial products to enter the bloodstream unfiltered, aggravating inflammation and causing diseases such as obesity and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Several studies have indicated that a change in diet can bring rapid changes to gut microbial communities. For example, a high-fat diet leads to mucus production impairment and increases barrier-disrupting microbial population which increases intestinal permeability [24].

Clinically, the membrane integrity can be tested by the Dual Sugar Absorption Test. In this test, sugars such as lactulose and mannitol are administered orally, and urinary excretion is measured. The blood biomarkers, such as zonulin, fatty-acid-binding proteins, and lipopolysaccharide-binding proteins in the samples provide indirect evidence for impaired integrity [25].

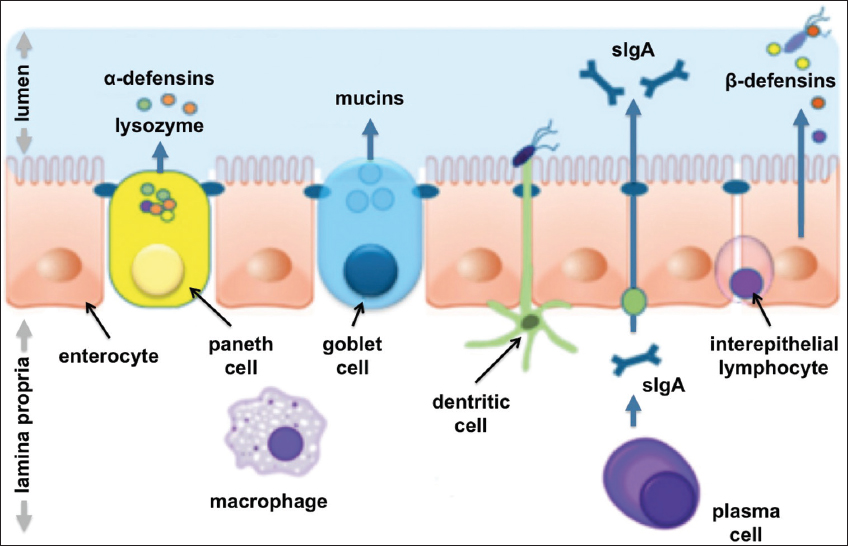

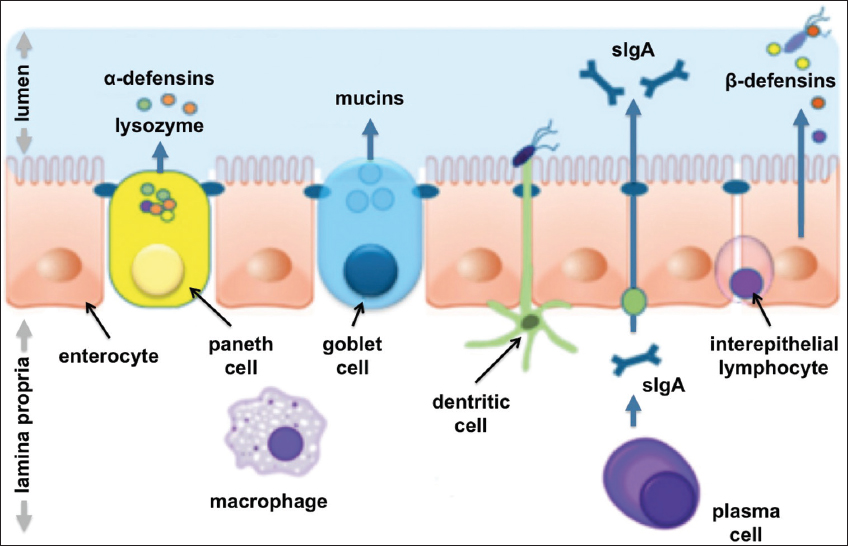

To understand the physiological implications of a leaky gut, it is necessary to know the structure of the barrier system. The mucosal barrier comprises four functional components: mechanical, chemical, immune, and biological, that work in a coordinated manner to maintain functional stability between the outside and the inside world [Figure 2]. The epithelial cells, including goblet cells, paneth cells, and absorptive cells, provide the defense layer of the intestinal mucosa [26]. These cells remain joined by junctional complexes, and include tight junctions (TJs), gap junctions, adherens junctions, and desmosomes that contribute to the mechanical barrier [27]. The intercellular TJ proteins are important for determining paracellular permeability, which is the movement of molecules through the intercellular spaces. The other route for microbes is the transcellular passage across epithelial cells. The paracellular route is significant for the transport of solutes or hydrophilic molecules that are smaller than 600 Da in size. This size limitation of proteinaceous molecules and other molecules, such as antigens, restricts their movement through the paracellular route [28]. However, when the intestinal integrity is compromised, pathogens, pro-inflammatory substances, and antigens enter the bloodstream. Such alteration in the environment might trigger a disease or an inflammation [29-31]. The TJ proteins bind to the actomyosin cytoskeleton and are in charge of the increased permeability to electrolytes and small molecules upon contraction [32].

| Figure 2: Key defense mechanisms of intestinal mucosa: Structural, immune, biochemical. Reference: Stephan C Bischoff DOI: 10.1186/s12876-014-0189-7© Bischoff et al.; license BioMed Central Ltd. 2014.

[Click here to view] |

Mucus in the intestine performs a critical function in the chemical barrier. It brings about bacteriolysis, meant to inhibit the invasion of pathogenic bacteria. This barrier is created by the digestive acids released by GIT digestive enzymes, along with other molecules, namely, mucopolysaccharides, glycoproteins, and glycolipids. GALT and secretory immunoglobulin A along with other cell types such as macrophages, the natural killer cells, and intraepithelial lymphocytes, constitute the immune barrier. This is necessary for maintaining intestinal immunity homeostasis [33,34].

A biological barrier is a stable and interrelated microecosystem composed of resident intestinal flora. The obligate anaerobes comprise the dominant bacterial community in the gut with less oxygen availability. It represents a mutually dependent relationship that continues to evolve with the host [35]. As a “virtual organ,” the gut microbiota is associated with metabolic processes, promotion of immune system maturation, and protection of neural function, and directly or indirectly also regulates both the physiological and pathological processes [36].

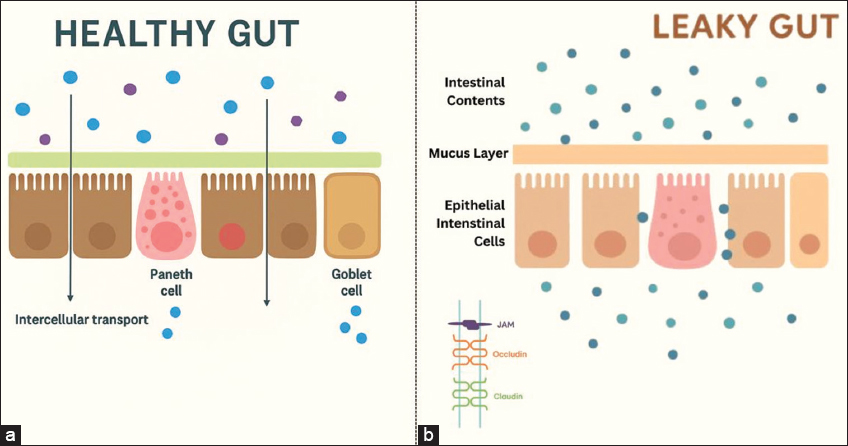

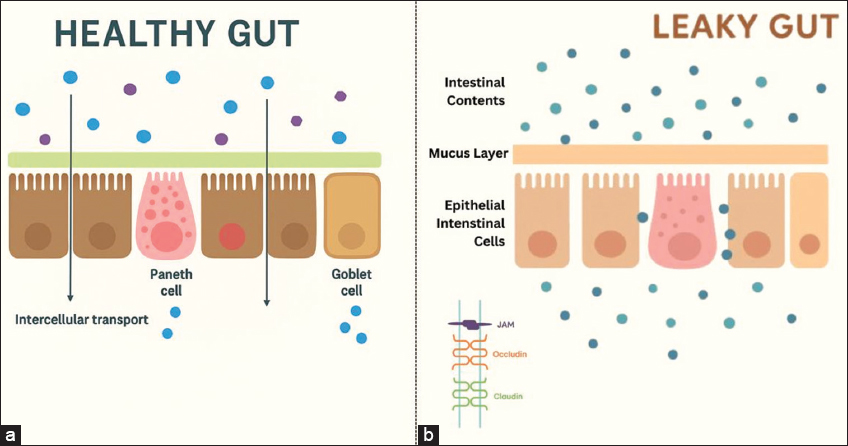

The intestinal integrity and intact epithelium are important for protecting the host against several diseases [10]. If this integrity is lost, the gut becomes leaky and permeable [Figure 3a and b]. In a leaky gut, the probability of leakage of bacterial components such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria is more, leading to a condition referred to as metabolic “endotoxemia” [37]. This increases the chances of inflammation, due to colonization and growth of pathogenic (pathobionts) microbes such as Clostridioides difficile, Helicobacter pylori, Helicobacter hepaticus, E. coli, and Proteus mirabilis. A similar leakage of commensal microbes contributes to allergy and autoimmune disorders [38]. These conditions of an imbalanced microbial population lead to diseases such as IBD, Clostridium difficile infection, celiac disease, obesity, colorectal cancer, and autism spectrum disorder. Further, studies reveal that besides the internal factors that make gut leaky, factors such as increased consumption of sugar, protein, or food additives, alcohol, drugs, lack of hygiene, anxiety, and stress also bring about bacterial translocation [39]. The bacterial species commonly translocated under such circumstances include E. coli, Klebsiella, Proteus, Enterobacter, Shigella, Salmonella, and Serratia. The leaky gut is responsible for the entry of LPS in the bloodstream and triggering low-grade inflammation, which further manifests in obesity. Furthermore, fat metabolism that leads to the formation of new fats and their storage in the adipose tissue is disturbed [40]. The SCFAs related to fat oxidation are also altered. The diet, too, correlates with dysbiosis. This is evidenced by the fact that during dysbiosis, bacteria present in the gut extract energy from indigestible carbohydrates of the diet. This leads to increased calorie absorption and obesity.

| Figure 3: (a and b) Intact mucosal barrier in “a” and a state of dysbiosis due to loss of integrity of mucosal barrier in “b”.

[Click here to view] |

The healthy pregnant women, when compared to non-pregnant women, experience higher intestinal permeability [57]. This increased permeability is due to a combination of physiological, metabolic, and anatomical changes that occur during pregnancy, which include uterine enlargement and changes in hormonal levels. During pregnancy, there is a significant rise in progesterone, estrogen, and thyroid levels. The alterations in gut microbiota accompany such changes. Though increased intestinal permeability is normal during pregnancy, an unusual rise in permeability may occur due to various pregnancy-related issues. Conditions such as recurrent pregnancy loss, gestational diabetes, overweight, and obesity are some such complications [58]. Moreover, gut inflammation is a significant factor that contributes to an elevated intestinal permeability.

REFERENCES

1. Valdes AM, Walter J, Segal E, Spector TD. Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. BMJ. 2018;361:2179.[CrossRef]

2. Flint HJ. The impact of nutrition on the human microbiome. Nutr Rev. 2012;70(Suppl 1):S10-3.[CrossRef]

3. Borre YE, O'Keeffe GW, Clarke G, Stanton C, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Microbiota and neurodevelopmental windows:Implications for brain disorders. Trends Mol Med. 2014;20(9):509-518.

4. Bäckhed F, Fraser CM, Ringel Y, Sanders ME, Sartor RB, Sherman PM, et al. Defining a healthy human gut microbiome:Current concepts, future directions, and clinical applications. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12(5):611-22.[CrossRef]

5. Tap J, Mondot S, Levenez F, Pelletier E, Caron C, Furet J, et al. Towards the human intestinal microbiota phylogenetic core. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11(10):2574-84.[CrossRef]

6. Dethlefsen L, Relman DA. Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4554-61.[CrossRef]

7. Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464(7285):59-65.[CrossRef]

8. O'Callaghan A, Van Sinderen D. Bifidobacteria and their role as members of the human gut microbiota. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:925.[CrossRef]

9. Kim G, Yoon Y, Park JH, Park JW, Noh MG, Kim H, et al. Bifidobacterial carbohydrate/nucleoside metabolism enhances oxidative phosphorylation in white adipose tissue to protect against diet-induced obesity. Microbiome. 2022;10:188.[CrossRef]

10. Power SE, O'Toole PW, Stanton C, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF. Intestinal microbiota, diet and health. Br J Nutr. 2014;111(3):387-402.[CrossRef]

11. Tang Q, Jin G, Wang G, Liu T, Liu X, Wang B, et al. Current sampling methods for gut microbiota:A call for more precise devices. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:151.[CrossRef]

12. Hooper LV, Gordon JI. Commensal host-bacterial relationships in the gut. Science. 2001;292(5519):1115-8.[CrossRef]

13. Cooke G, Behan J, Costello M. Newly identified vitamin K-producing bacteria isolated from the neonatal faecal flora. Microbial Ecol Health Dis. 2006;18(3-4):133-8.[CrossRef]

14. Geleijnse JM, Vermeer C, Grobbee DE, Schurgers LJ, Knapen MH, Van Der Meer IM, et al. Dietary intake of menaquinone is associated with a reduced risk of coronary heart disease:The Rotterdam study. J Nutr. 2004;134(11):3100-5.[CrossRef]

15. Andrès E, Loukili NH, Noel E, Kaltenbach G, Abdelgheni MB, Perrin AE, et al. Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency in elderly patients. CMAJ. 2004;171(3):251-9.[CrossRef]

16. Gominak C. Vitamin D deficiency changes the intestinal microbiome reducing B vitamin production in the gut. The resulting lack of pantothenic acid adversely affects the immune system, producing a “pro-inflammatory“state associated with atherosclerosis and autoimmunity. Med Hypotheses. 2016;94:103-7.[CrossRef]

17. Mayer EA, Savidge T, Shulman RJ. Brain-gut microbiome interactions and functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(6):1500-12.[CrossRef]

18. Staels B, Fonseca VA. Bile acids and metabolic regulation:Mechanisms and clinical responses to bile acid sequestration. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(Suppl 2):S237.[CrossRef]

19. Ridlon JM, Ikegawa S, Alves JM, Zhou B, Kobayashi A, Iida T, et al. Clostridium scindens:A human gut microbe with a high potential to convert glucocorticoids into androgens. J Lipid Res. 2013;54(9):2437-49.[CrossRef]

20. Ciccia F, Guggino G, Rizzo A, Alessandro R, Luchetti MM, Milling S, et al. Dysbiosis and zonulin upregulation alter gut epithelial and vascular barriers in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(6):1123-32.[CrossRef]

21. Cox LM, Weiner HL. Microbiota signaling pathways that influence neurologic disease. Neurotherapeutics. 2018;15(1):135-45.[CrossRef]

22. Makris AP, Karianaki M, Tsamis KI, Paschou SA. The role of the gut-brain axis in depression:Endocrine, neural, and immune pathways. Hormones (Athens). 2021;20(1):1-12.[CrossRef]

23. Twardowska A, Makaro A, Binienda A, Fichna J, Salaga M. Preventing bacterial translocation in patients with leaky gut syndrome:Nutrition and pharmacological treatment options. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(6):3204.[CrossRef]

24. Paone P, Cani PD. Mucus barrier, mucins and gut microbiota:The expected slimy partners?Gut. 2020;69(12):2232-43.[CrossRef]

25. Bischoff SC, Barbara G, Buurman W, Ockhuizen T, Schulzke JD, Serino M, et al. Intestinal permeability--a new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:189.[CrossRef]

26. Chen Y, Cui W, Li X, Yang H. Interaction between commensal bacteria, immune response and the intestinal barrier in inflammatory bowel disease. Front Immunol. 2021;12:761981.[CrossRef]

27. Zhao X, Zeng H, Lei L, Tong X, Yang L, Yang Y, et al. Tight junctions and their regulation by non-coding RNAs. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17(3):712.[CrossRef]

28. Molotla-Torres DE, Guzmán-Mejía F, Godínez-Victoria M, Drago-Serrano ME. Role of stress on driving the intestinal paracellular permeability. Curr Issues Mol Biol.2023;45(11):9284-305.[CrossRef]

29. France MM, Turner JR. The mucosal barrier at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2017;130(2):307-14.[CrossRef]

30. Durantez Á, Gómez S. Agujeros. Intestino Síndrome de Hipermeabilidad Intestinal;2018. 35. Available from: https://drdurantez.es/blog/2018/09/04/agujeros-en-el-intestino-sindrome-dehipermeabilidad-intestinal [Last accessed on 2025 Mar 10].

31. Iweala OI, Nagler CR. The microbiome and food allergy. Annu Rev Immunol. 2019;37(1):377-403.[CrossRef]

32. Nusrat A, Turner JR, Madara JL. Molecular physiology and pathophysiology of tight junctions. IV. Regulation of tight junctions by extracellular stimuli:Nutrients, cytokines, and immune cells. Am J Physiol. 2000;279(1):G851-7.[CrossRef]

33. Quiroz-Olguín G, Gutiérrez-Salmeán G, Posadas-Calleja JG, Padilla-Rubio MF, Serralde-Zúñiga AE. The effect of enteral stimulation on the immune response of the intestinal mucosa and its application in nutritional support. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2021;75(11):1533-9.

34. Li T, Wang C, Liu Y, Li B, Zhang W, Wang L, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps induce intestinal damage and thrombotic tendency in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn's Colitis. 2020;14(2):240-53. [CrossRef]

35. Adak A, Khan MR. An insight into gut microbiota and its functionalities. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019;76:473-93.[CrossRef]

36. Koboziev I, Reinoso Webb C, Furr KL, Grisham MB. Role of the enteric microbiota in intestinal homeostasis and inflammation. Free Radical Biol Med. 2014;68:122-33.[CrossRef]

37. Cani PD, Osto M, Geurts L, Everard A. Involvement of gut microbiota in the development of low-grade inflammation and type 2 diabetes associated with obesity. Gut Microbes 2012;3(4):279-88.[CrossRef]

38. Cui X, Cong Y. Role of Gut microbiota in the development of some autoimmune diseases. J Inflamm Res. 2025;18:4409-19.[CrossRef]

39. Belizário JE, Faintuch J. Microbiome and gut dysbiosis. Exp Suppl. 2018;109:459-76.[CrossRef]

40. Carabotti M, Scirocco A, Maselli MA, Severi C. The gut-brain axis:Interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28(2):203-9.

41. De Goffau MC, Lager S, Sovio U, Gaccioli F, Cook E, Peacock SJ, et al. Human placenta has no microbiome but can contain potential pathogens. Nature. 2019;572(7769):329-34.[CrossRef]

42. Bokulich NA, Chung J, Battaglia T, Henderson N, Jay M, Li H, Blaser MJ. Antibiotics, birth mode, and diet shape microbiome maturation during early life. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(343):343ra82.[CrossRef]

43. La Rosa PS, Warner BB, Zhou Y, Weinstock GM, Sodergren E, Hall-Moore CM, et al. Patterned progression of bacterial populations in the premature infant gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111(34):12522-7.[CrossRef]

44. Koenig JE, Spor A, Scalfone N, Fricker AD, Stombaugh J, Knight R, et al. Succession of microbial consortia in the developing infant gut microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;108(Suppl 1):4578-85.[CrossRef]

45. Perez-Munoz ME, Arrieta MC, Ramer-Tait AE, Walter J. A critical assessment of the “sterile womb“and “in utero colonization“hypotheses:Implications for research on the pioneer infant microbiome. Microbiome. 2017;5(1):48.[CrossRef]

46. Bushman FD. De-discovery of the placenta microbiome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(3):213-4.[CrossRef]

47. Xie Z, Chen Z, Chai Y, Yao W, Ma G. Unveiling the placental bacterial microbiota:Implications for maternal and infant health. Front Physiol. 2025;1(16):1544216.[CrossRef]

48. Park JY, Yun H. Comprehensive characterization of maternal, fetal, and neonatal microbiomes supports prenatal colonization of the gastrointestinal tract. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):4652.[CrossRef]

49. Broens PM, Van Rooij IA, Bagci S, Brosens E, Tibboel D, De Klein A, et al. More than fetal urine:Enteral uptake of amniotic fluid as a major predictor for fetal growth during late gestation. Eur J Pediatr. 2016;175:825-31. [CrossRef]

50. Trahair J. Digestive system. In:Harding R, Bocking AD, editors. Fetal Growth and Development. Cambridge UK:Cambridge University Press;2001. 137-153.

51. Gitlin D, Kumate J, Morales C, Noriega L, Arévalo N. The turnover of amniotic fluid protein in the human conceptus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972;113:632-45.[CrossRef]

52. Stinson L. The Not-so-Sterile Womb:New Data to Challenge An Old Dogma. PhD Thesis Submitted to University of Western Australia.

53. Brown J, De Vos WM, DiStefano PS, DoréJ, Huttenhower C, Knight R, et al. Translating the human microbiome. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(4):304-8.[CrossRef]

54. Dunn AB, Jordan S, Baker BJ, Carlson NS. The maternal infant microbiome:Considerations for labor and birth. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2017;42(6):318-25.[CrossRef]

55. Walker RW, Clemente JC, Peter I, Loos RJ. The prenatal gut microbiome:Are we colonized with bacteria in utero?Pediatr Obes. 2017;12(Suppl 1):3-17.[CrossRef]

56. Kerr CA, Grice DM, Tran CD, Bauer DC, Li D, Hendry P, et al. Early life events influence whole-of-life metabolic health via gut microflora and gut permeability. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2015;41(3):326-40.[CrossRef]

57. Ma G, Chen Z, Xie Z, Liu J, Xiao X. Mechanisms underlying changes in intestinal permeability during pregnancy and their implications for maternal and infant health. J Reprod Immunol. 2025;168:104423.[CrossRef]

58. Amabebe E, Anumba DO. The vaginal microenvironment:The physiologic role of lactobacilli. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:181.[CrossRef]

59. Amir M, Brown JA, Rager SL, Sanidad KZ, Ananthanarayanan A, Zeng MY. Maternal microbiome and infections in pregnancy. Microorganisms. 2020;8(12):1996.[CrossRef]

60. Tang M, Weaver NE, Frank DN, Ir D, Robertson CE, Kemp JF, et al. Longitudinal Reduction in diversity of maternal gut microbiota during pregnancy is observed in multiple low-resource settings:Results from the women first trial. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:823757.[CrossRef]

61. Koren O, Goodrich JK, Cullender TC, Spor A, Laitinen K, Bäckhed HK, et al. Host remodeling of the gut microbiome and metabolic changes during pregnancy. Cell. 2012;150(3):470-480.[CrossRef]

62. Walters WA, Xu Z, Knight R. Meta-analyses of human gut microbes associated with obesity and IBD. FEBS Lett. 2014;588(22):4223-33.[CrossRef]

63. Edwards SM, Cunningham SA, Dunlop AL, Corwin EJ. The maternal gut microbiome during pregnancy. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2017;42(6):310-7.[CrossRef]

64. Liang X, Wang R, Luo H, Liao Y, Chen X, Xiao X,et al. The interplay between the gut microbiota and metabolism during the third trimester of pregnancy. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:1059227.[CrossRef]

65. Neuman H, Koren O. The pregnancy microbiome. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2017;88:1-9.[CrossRef]

66. Vijay-Kumar M, Aitken JD, Carvalho FA, Cullender TC, Mwangi S, Srinivasan S, et al. Metabolic syndrome and altered gut microbiota in mice lacking Toll-like receptor 5. Science. 2010;328(5975):228-31.[CrossRef]

67. Tilg H, Moschen AR. Adipocytokines:Mediators linking adipose tissue, inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(10):772-83.[CrossRef]

68. Huang B, Fettweis JM, Brooks JP, Jefferson KK, Buck GA. The changing landscape of the vaginal microbiome. Clin Lab Med. 2014;34(4):747-61.[CrossRef]

69. Biasucci G, Rubini M, Riboni S, Morelli L, Bessi E, Retetangos C. Mode of delivery affects the bacterial community in the Newborn gut. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86(Supp 1):13-15.[CrossRef]

70. Penders J, Thijs C, Vink C, Stelma FF, Snijders B, Kummeling I, et al. Factors influencing the composition of the intestinal microbiota in early infancy. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):511-21.[CrossRef]

71. Pivrncova E, Kotaskova I, Thon V. Neonatal diet and gut microbiome development after C-section during the first three months after birth:A systematic review. Front Nutr. 2022;9:941549.[CrossRef]

72. Shao Y, Forster SC, Tsaliki E, Vervier K, Strang A, Simpson N, et al. Stunted microbiota and opportunistic pathogen colonization in caesarean-section birth. Nature. 2019;574(7776):117-21.[CrossRef]

73. Guaraldi F, Salvatori G. Effect of breast and formula feeding on gut microbiota shaping in newborns. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:94.[CrossRef]

74. Walker WA, Iyengar RS. Breast milk, microbiota, and intestinal immune homeostasis. Pediatr Res. 2015;77:220-8.[CrossRef]

75. Palmer C, Bik EM, DiGiulio DB, Relman DA, Brown PO. Development of the human infant intestinal microbiota. PLoS Biol. 2007;5(7):177.[CrossRef]

76. McCann A, Ryan FJ, Stockdale SR, Dalmasso M, BlakeT, Ryan CA, et al. Viromes of one year old infants reveal the impact of birth mode on microbiome diversity. PeerJ. 2016;6:4694.[CrossRef]

77. Shennon I, Wilson BC, Behling AH, Portlock T, Haque R, Forrester T, et al. The infant gut microbiome and cognitive development in malnutrition. Clin Nutr. 2024;43(5):1181-9.[CrossRef]

78. Zhou L, Qiu W, Wang J, Zhao A, Zhou C, Sun T, et al. Effects of vaginal microbiota transfer on the neurodevelopment and microbiome of cesarean-born infants:A blinded randomized controlled trial. Cell Host Microbe. 2023;31(7):1232-47.[CrossRef]

79. Rodríguez JM, Murphy K, Stanton C, Ross RP, Kober OI, et al. The composition of the gut microbiota throughout life, with an emphasis on early life. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2015;26:26050.[CrossRef]

80. Claesson MJ, Cusack S, O'Sullivan O, Greene-Diniz R, De Weerd H, Flannery E, et al. Composition, variability, and temporal stability of the intestinal microbiota of the elderly. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4586-591.[CrossRef]

81. Odamaki T, Kato K, Sugahara H, Hashikura N, Takahashi S, Xiao JZ, et al. Age-related changes in gut microbiota composition from newborn to centenarian:A cross-sectional study. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16:90.[CrossRef]

82. Salazar N, Arboleya S, Valdés, L, Stanton C, Ross P, Ruiz L, et al. The human intestinal microbiome at extreme ages of life. Dietary intervention as a way to counteract alterations. Front Genet. 2014;5:406.[CrossRef]

83. Jackson MA, Jeffery IB, Beaumont M, Bell JT, Clark AG, Ley RE, et al. Signatures of early frailty in the gut microbiota. Genome Med. 2016;8:8.[CrossRef]

84. Zhang D, Huang Y, Ye D. Intestinal dysbiosis:An emerging cause of pregnancy complications? Med Hypotheses. 2015;84(3):223-26.[CrossRef]

85. Zmora N, Suez J, Elinav E. You are what you eat:Diet, health and the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:35-56.[CrossRef]

86. Planer JD, Peng Y, Kau AL, Blanton LV, Ndao IM, Tarr PI, et al. Development of the gut microbiota and mucosal IgA responses in twins and gnotobiotic mice. Nature. 2016;534(7606):263-6.[CrossRef]

87. Mkilima T. Engineering artificial microbial consortia for personalized gut microbiome modulation and disease treatment. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2025;1548(1):29-55.[CrossRef]