1. INTRODUCTION

Aerides have a distinct growth pattern with numerous attractive leaves. The flowers are highly fragrant and the plants are average sized epi- and/or lithophytes with bright pink flowers. The epiphytic evolution process, which is unusual among experts in the 18th century, is referred to by the scientific word (gr. Aer = air, eides = emerges) [1]. Aerides odorata is a species of Orchidaceae family. It can be found in China’s forests (Yunnan, Guangdong), Himalayas, Bhutan, Assam, Bangladesh, and India (Manipur, Uttarakhand, West Bengal’s Darjeeling Himalayas, and Arunachal Pradesh), Nepal, Nicobar and Andaman Island, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Sumatra, Borneo, Java, Sulawesi, and Philippines (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A. odorata). A tropical or subtropical forest is its native habitat. More endangered species, such as the Aerides, require immediate and in situ preservation. Furthermore, because these species’ seeds lack endosperm and require fungal stimulation to germinate in the environment, their spread by sexual activity is slow; the mold is thought to boost glucose, auxin, and vitamin transport in the orchid. In a range of plants and settings, endophytic fungi have been researched. In addition, fungal endophytes release various enzymes, including cellulases, pectinase, and lipase, which penetrate and assist their colonization of host skins [2-4].

The loss of orchid value variety is a cause for concern, and conservation strategies such as hybridization as well as in vitro dissemination remain crucial. Hybridization of Aerides adds a new height to the floriculture sector by allowing for the continuing development of better kinds. Pollen is required for orchids to develop pods and genetic diversity in wild populations is heavily reliant on the opposite fertilization. Pollen ecosystems, on the other hand, are threatened by climate change and deforestation. Furthermore, Orchid metabolites have been shown to be beneficial against human ailments. They play a crucial role in cancer prevention and treatment. Fatty acids, the following alcohol, diketones, esters, and phenols are found in phytochemical examination of A. odorata species. These secondary metabolites might have a wide range of natural therapeutic plant properties. The majority of the compounds found in this plant’s ethyl acetate and methanol extracts are physiologically active [5]. The presence of a specific fungal species is required for the development of orchid seeds. However, the rate of vegetable distribution is slow, and environmental germination is low, ranging from 0.2 to 0.5%. Because microscopic seed-like dust has the capacity to grow into entire seedlings without the help of fungal spores, in vitro germination is a key step in the orchid’s replication and preservation process [6]. Commercial orchid horticulture, both commercially cultivated and cut flower production, has improved in several countries, with flower sales reaching millions of dollars. Orchid flowers command the greatest price on the international market due to its incredible range of size, shape, and gorgeous color combinations [7].

The review article’s main goal is to thoroughly examine 10-year land distribution data and indicators. A. odorata, current research methods and development process, including taxonomic methods for identification, seed germination and seedling development, hybridization methods, collaborative methods, the most versatile plant regeneration program, and endophytic variations, disease profile, various uses, and discussion of need, challenges, and future vision.

For the purpose of demonstrating the current study and assessing the possible insights in the literature on A. odorata research methodologies and process progress, endophytic variants, and disease profiles, the paper included articles from the previous 10 years. As a critical review, a list of essential keywords was selected, and a search of all available databases was performed (i.e., Scopus, Web of Knowledge, and Google Scholar). Using specific keywords and numbers, including A. odorata (810), global distribution (354), current research approaches and process advancement (244), fungal profile (43), disease profile (70), biological activity (278), and need, challenges, and future outlook, the available papers were evaluated critically (82). To catch up, essential data were extracted. The categorization of research and the creation of a database of publications were essential steps. In addition, the study evaluates the entire spectrum of current A. odorata research methodologies and process development, as well as their proven biological activities and disease profile. To aid plant biotechnologists and pathologists in utilizing the enormous bioresources and developing them into marketable products, the research is comprehensive.

2. GLOBAL DISTRIBUTION AND CHARACTERISTICS’ OF A. ODORATA

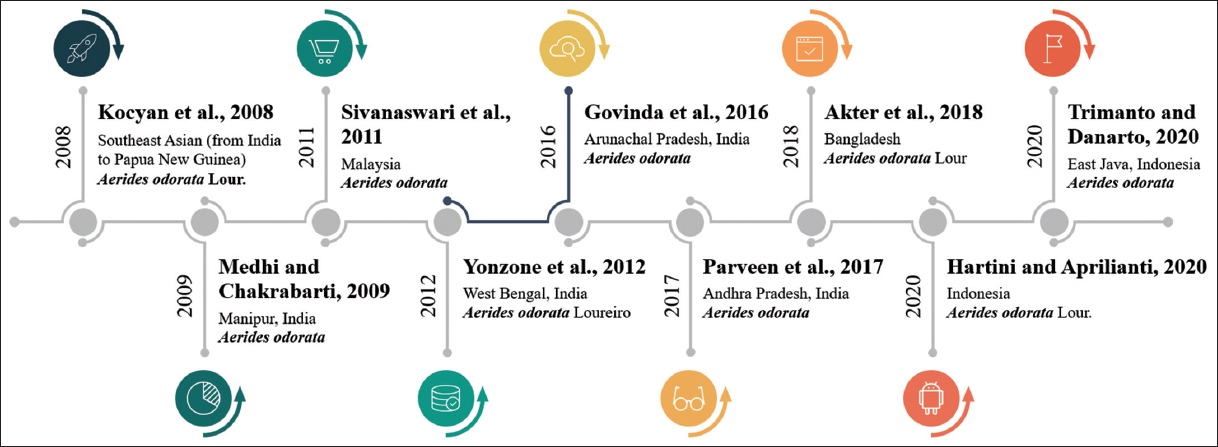

Aerides Lour. has roughly 21 species of orchids native to Southeast Asia, ranging from India to Papua New Guinea [1]. Manipur, in northeastern India, is known for its orchid diversity, ranking fourth in the world [8]. Aerides is a commercial and valuable medical orchid among the 251 species of wild orchids found in Manipur. A. odorata, A. odorata var. “Yellow,” Aerides flabellata, and Aerides quinquevulnera var. calayana are fragrant wild Aerides variants that are extensively dispersed in Malaysia [9]. One orchid species, A. odorata Lour is collected from Near Kaptai National Park in Rangamati, Bangladesh [10]. Other exploratory endeavors discovered C. Finlay sonianum and A. odorata Lour in Polali Mandar and Bantimurung Bulusaraung National Park, Indonesia [11]. The epiphytic pot originate in the Eastern area of Andhra Pradesh’s Vizianagaram region still contains A. odorata. A. odorata was discovered in Uttarakhand’s Dhunar Gaon [12]. At Bawean Island Nature Reserve and Wildlife Reserve in East Java, Indonesia, Aerides orders have been discovered [13]. A. odorata were obtained from the Tipi Orchid Research Center’ sat Arunachal Pradesh, India [3]. A. odorata Loureiro is also reported from the Darjeeling Himalayas of West Bengal, India [14]. Prasad et al. [15] investigated the epiphytic orchid A. odorata, which belongs to the Orchidaceae family and is found in tropical and subtropical climes. This plant is not native to India; yet, it has been recorded to grow in several locations of the country. The diversity of plant has reported and details presented in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1: Global distribution and characteristics of Aerides odorata.

| Year | Region | Diversity | Reported Disease | Phylogenetic identification tools | Key characteristics features | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

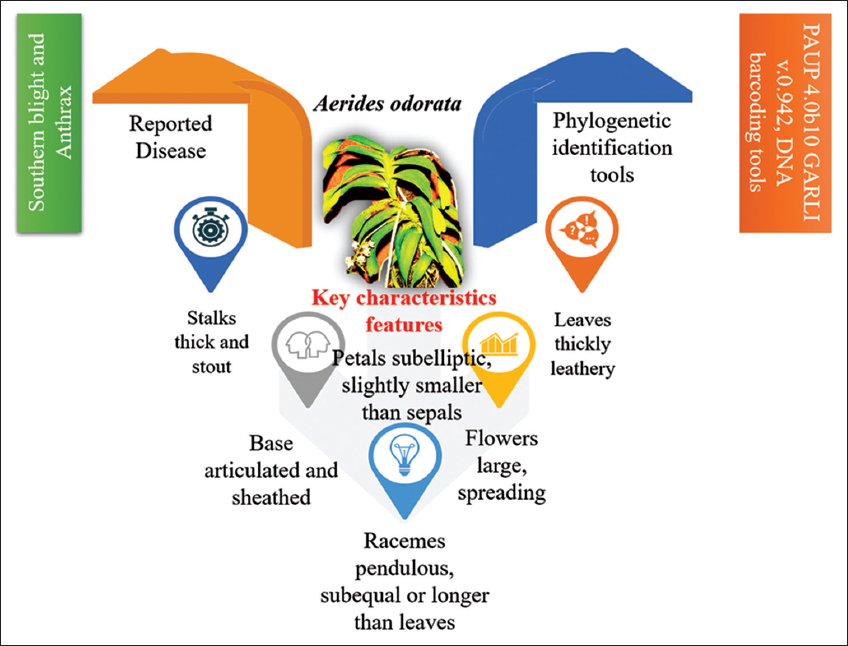

| 2008 | Southeast Asian (from India to Papua New Guinea) | Aerides odorata Lour. | Southern blight and Anthrax | Phylogenetic identification using the PAUP 4.0b10 GARLI v. 0.942, DNA barcoding tools | Staves that are thick and stocky, leaves that are densely leathery, broadly banded, 15–20 centimetres in length, 2.5–4.6 cm in width, apexes that are obtuse and 2-lobed unequally, and bases that are articulated and sheathed; Racemes that are pendulous and either subequal in length to the leaves or longer than they are; The flowers are huge, spreading, about 3 millimetres in diameter, fragrant, and white to pinkish in colour; Petals are subelliptic in shape, somewhat smaller than the sepals, obtuse at the apex, and thin at the base. | [1] |

| 2009 | North-east India, Manipur, India | Aerides odorata | [8] | |||

| 2011 | Malaysia | Aerides odorata | [9] | |||

| 2012 | West Bengal, India | Aerides odorata Loureiro | [14] | |||

| 2016 | Arunachal Pradesh, India | Aerides odorata | [3] | |||

| 2016 | India | Aerides odorata | [15] | |||

| 2017 | Andhra Pradesh, India | Aerides odorata | [12] | |||

| 2018 | Bangladesh | Aerides odorata Lour. | [10] | |||

| 2020 | Indonesia | Aerides odorata Lour. | [11] | |||

| 2020 | East Java, Indonesia | Aerides odorata | [13] |

| Figure 1: General characteristics features, diseases, and phylogenetic tools of Aerides odorata. [Click here to view] |

A. odorata has dense and robust stems. The leaves of A. odorata are thick, broad, 15–20 cm extended and 2.5–4.6 cm wide, with an obtuse apex and two unequal lobes, and a distinct and burnt base. The racemes are splendid, lasting as long as or longer than the leaves, which hold a lot of information; the blooms are huge, spreading, and about 3 cm wide. The petals are sub-subelliptic with an obtuse apex and a base less. A. odorata has a nice odor and a white blossom with a pinkish tinge [7]. In the months of May–July, A. odorata Lour., an epiphyte plant with a white-purple tint, blooms [16]. Other species are included as Aerides multiflora, A. odorata, Rhyncho stylisretusa, Dendrobium amoenum, Pholidata articulata, and Smitihandia micrantha [17] [Figure 2].

| Figure 2: Year-wise global distribution of Aerides odorata. [Click here to view] |

3. CURRENT RESEARCH APPROACHES AND PROCESS ADVANCEMENT

3.1. Phylogenetic Methods of Diagnosis

Phylogenetic cell investigations have been concentrated on various Aeridinae groupings, including leafless vandoids and phalaenopsis. Based on nrITS data, Carlsward et al. [18] identified Adenoncos and Vandopsis as near relatives of Aerides [1]. (phylogenetic analysis using parsimony) v4.0b10 for reconstruction of parsimony, (genetic algorithm for rapid likelihood inference) v.0.942 (genetic predisposition for rapid acquisition), and Bayes v3.1.2 for Bayesian analysis and preliminary calculations were used for phylogenetic analysis [1]. The species found in Thailand and Vietnam constituted a well-supported subclade within the Aerides clade (A. falcata var. Houlletiana, Amanita rubescens, A. odorata var. bicuspidate). Polymorphic sites were found in Aerides huttonii, A. odorata, A. odorata var. bicuspidata, single placements of Aerides leeana, A. multiflora, Aerides thibautiana, Aerides lawrenciae, Seidenfadenia mitrata, Vanda flabellata, and Vanda tricolour. The existence of five mutations and a 1 bpindel in the 5.8 S gene of all three species also supports consecutive nrITS clones of A. orthopaedic pseudogenes. A. leeana, A. lawrenciae, A. quinquevulnera, and A. odorata comprised a diversified group of creatures from the Philippines and Borneo in the family of Aerides [1]. Parveen et al. [12] examined the discriminatory capacity of the five types of loci, ITS matK, rbcL, rpoB, and rpoC1, in the context of DNA barcoding as a potential diagnostic tool.

3.2. Seed Germination and Seedling Development

Because A. odorata seeds are tiny and contain only one incomplete embryo, their germination capacity is poor. Furthermore, because the seed skin is difficult to engross water, it will not germinate using traditional sowing approaches. To provide nutrients for germination, the A. odorata fungus or artificial insemination are required. Fruit is best to choose non-destructive, which contains 75% alcohol afterward sterilization, take away seeds, add sodium hypochlorite (10%) for 5–10 min, extract with clean water, stir, and move to light which can create the first lamp. When the circumstances allow, tissue culture can be distributed in this manner. For the quick spread of A. odorata, Sarmah et al., [19] received several explants and employed 1/2 MS (Murashige and Skoog) medium, along with thidiazuron (TDZ), 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP), and leaf base. They used an average of 1.0 mg/L TDZ to create protocorm like bodies (PLBs) at the leaf’s base. The media containing 2 mg/L (NAA: 1-naphthaleneacetic acid) as well as direct shot stimulation with NAA (2 mg/L) and BAP (4 mg/L) had the highest frequency of calli intake from baseline screening after 60 days of culture. The most root implants were found in media containing and MS with 0.5 mg/L NAA [19].

When examining the influence of the controls growth, the young A. odorata protocorms were developed, as reported in Table 1. Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) was employed to produce roots, whereas NAA and BAP were used to produce new shoots. In 120 days of culture, protocorms in MS media without growth controls produced 2.66 (number per cutting) new shoots. In 180 days of culture, each new shoot produces 2.0 leaves and 1.66 root numbers (number per cutting). New shoots were formed when BAP and NAA were combined in a nutritive environment; the intermediate MS dose combining BAP 0.5 mg/L and NAA 1.0 mg/L resulted in a very high 5.0 number of new shoots. In comparison to MS media, shoots also produce more leaves and roots. The presence of IBA in the genetic region resulted in additional shoots, but the impacts were minimal. Each shoot developed 2.66 leaves and 3.33 roots thanks to growth regulators. The number of individual flowers (23), length spike (20.87), and peduncle length (8.61) of A. odorata plants were improved when nutrients were applied every 10 days of the NPK interval at 40:10:10 (initial burst) and 25:50:50 (improves flowering) compared to other treatments [20].

3.3. Hybridization Methods

The typical spread of disease, such as the emergence of plants, is a sluggish process. Furthermore, mycorrhizal organization is required for orchid seed dissemination to germinate. Seed germination with nutrient-rich fertilizers can thus be a quick tool. Orchid seeds can grow into light sugars with a medium outside the fungal organization, this method of growing was modified. Aerides odorota, A. odorota var. “Yellow,” A. quinquevulnera var. calayana, and A. flabellata are all wild species [9,21]. A. odorata as a female resulted in a 0–60% successful fall, while A. odorata as a male resulted in a 25–62 % successful fall. The morphology of an orchid flower is a little more complicated, with a stem structure called a column and an anther with pollen inside called a pollinarium in the apical region of the column. The sting is located in the rostellum, which is the lower apical column. When pollinarium can be inserted in a rostellum, pollination is successful [22].

The crosses sought to develop the initial compounds utilized to explore the properties of kinetin concentration and BAP on the fraction of a germination. A. odorata, A. quinquevulnera var. calayana, A. quinquevulnera, A. odorata var. “Yellow,” A. odorata, A. flabellata and their retaliation were among the six crosses. A. odorata var. ‘Yellow’, A. quinquevulnera var. calayana had the largest proportion of successful crosses (80%), while A. flabellata, A. odorata had the lowest (25%). A. odorata, A. quinquevulnera var. calayana and its retaliation had 60 and 62%, respectively. A. quinquevulnera var. calayana, A. odorata var.’Yellow, A. quinquevulnera var. calayana pods ripened in 76 days, A. flabellate, A. odorata pods in 116 days, A. odorata, A. quinquevulnera var. calayana pods in 179 days, and A. odorata, A. quinquevulnera var. calayana pods in 184 days, A. flabellata and A. odorata had the largest pods, whereas A. odorata var. “Yellow” and A. quinquevulnera var. calayana had the smallest. There was a substantial variation in seed germination percentages between A. odorata and A. quinquevulnera var. calayana, with the greatest being 1.5 mg/L kinetin and the lowest being 2.0 mg/L BAP [9].

3.4. Co-culturing Approach

A. odorata requires mycorrhizal fungus to produce dust seeds, which supply carbon and mineral resources to stimulate protocorms and plant growth in the environment. Aerides seeds from blue and yellow tablets are currently being used for in vitro symbiotic germination. In the oat meal agar medium, which is the most often used substrate for evaluating symbiotic germination, they are made up of both (AM301 and AM302) fungal isolates. In cultures incorporating Ceratobasidium sp. (set AM301), the highest percentage of seed germination (87.00 ± 1.32) was found, while the lowest (74.28 ± 1.10) was controlled. When planted with Lasiodiplodia theobromae, 78.66 ± 2.10% of the seeds germinated (separating AM302). Both fungi’s fungal hyphae encircled and entered the seed’s general surface. By activating the rhizosphere soil nutrients, fungal endophytes can enhance Orchidaceae growth. The impact on changes in the number of SMs is also specified. Overall, the Orchidaceae should be protected from soil microbes by a living chemical source. Sustainable symbiotic orchid germination has become a common and significant method of propagating the seed, particularly, where species are required for the co-planting system’s renewal [4].

3.5. High-frequency Recovery System

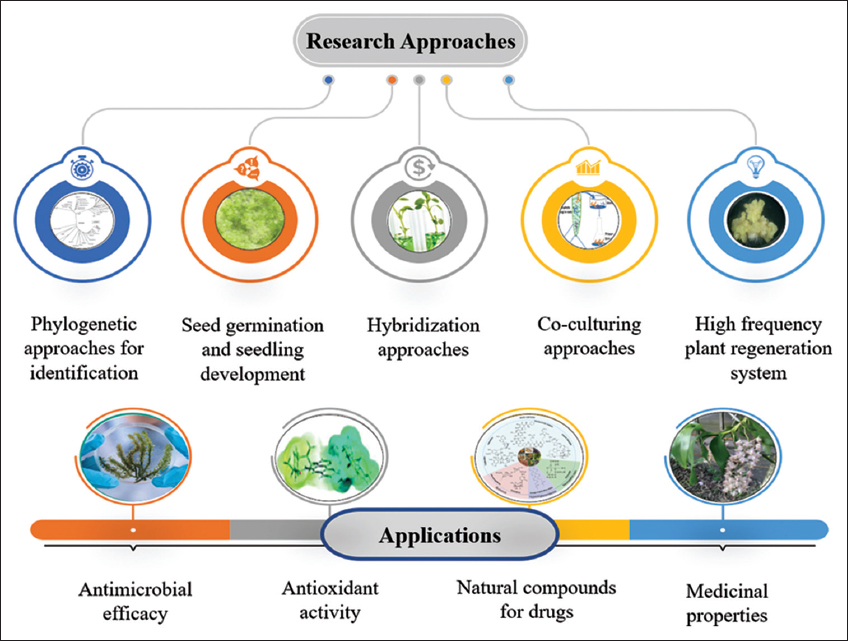

PLBs stimulation has been proven to be effective when cytokinins and auxins are coupled. Many orchid species, such as Aranda, Vanda, and Phalaenopsis, employ Vandas sps., Rhynchostylis gigantean, and NAA in combination with Benzyladenine (BA). The combination of NAA (1.0 mM) and BA (0.5 mM) resulted in complete regeneration of PLB in the current investigation; however, the effects were greatly reduced when compared to BA therapy alone. Many orchids have been effectively dispersed using liquid endosperm liquid. Protocorms and leaf extracts have reacted poorly to coconut liquid endosperm supplementation in recent investigations. The use of the protocol and leaf clusters to regenerate a large number of PLBs, and then the previous layers using the protocol and leaf clusters tried here, can aid in the widespread dispersion of decorative Aerides species [23]. During the experiment, useful techniques for mass distribution of A. odorata Lour. were developed. Statistical examination of shoot repetition in the MS medium using a variety of NAA, TDZ, and BAP combinations and filters revealed a very large (p 0.5) difference in the number of shoots produced by different medications [24]. In the strength of MS semisolid, medium injections of 1.0 mg/L NAA with 2.0 mg/L BAP in standard bottles with polypropylene lids, an A. odorata plant can thrive for up to 12 months. The cultures can be maintained for longer than 24 months if liquid culture media with the same nutritional content is added at regular intervals. This does not need the seedlings to be moved from one culture vessel to another; however, the development of successful storage methods allows the establishment of extensive basal collections with representative genetic diversity [24] [Figure 3].

| Figure 3: Research approaches and applications of Aerides odorata. [Click here to view] |

4. FUNGAL PROFILE OF A. ODORATA

Endophytes are endosymbionts that live in harmony with bacteria, fungus, and actinomycetes within plants. Endophytic fungi are essential sources of active compounds, because they reside on healthy plant components such as leaves, stems, and roots [2]. Aerides leaves, stems, and roots separated a total of 52 endophytes. Fungal endophytes were detected in greater numbers in the leaves (27) than in the roots (17) or stem tissue (8) [2]. Endophytes are fungi that reside in the tissues of underground and underground plants and are invisible to the naked eye. Due to their ability to synthesize novel bioactive compounds and industrial enzymes, as well as their ability to relieve abiotic and biotic stress in the plants they live in, endophytes are less likely to be bioprospecting. Endophytes displayed tissue specificity, with a small overlap between the junction’s leaf and roots. Xylaria species were abundant, separated from roots and leaves of A. odorata species [3]. Xylaria spp. were found in both the leaves and the roots. The diversity of endophytes was higher in the leaves and tissue specificity was shown [25]. Species diversity and colonization frequency % of endophytes isolated from leaves of A. odorata orchid species are reported as Cladosporium sp. 3, Colletotrichum sp. 39, Fusarium sp. 1 1, Phomopsis sp. 1, Phyllosticta capitalensis 11, Xylaria sp. 112, and Xylaria sp. 33 [3].

The anamorphic Rhizoctonia is represented by a large range of fungi discovered in orchid mycorrhizae. Sebacina, Thanatephorus, and Tulasnella are teleomorphic species. Basidiomycetes, such as Armillaria, Coriolus, Favolaschia, Fomes, Hymenochaete, Marasmius, Thelephora, Tomentella, and Xerotus, are frequently paralyzed by chlorophyllous-free orchids. Many of these fungi are saprophytic, meaning they can decompose dead creatures and release them into the soil. Plant pathogens such as Armillaria mellea, Rhizoctonia solani, and Thanatephorus cucumeris are well-known, and some are ectomycorrhizal in the roots of particular plants [26]. Orchid mycorrhiza, in conjunction with a fungal companion, is a requirement for the emergence of orchid seeds. Most orchid mycorrhizal fungi belong to the Rhizoctonia genus, which includes R. repens, R.mucoroides, and R.languinosa. To find healthy food molecules, fungi constantly strive to penetrate the cytoplasm of orchid cells. Orchid cells, on the other hand, consume entering hyphae to slow down their growth and absorb nutrients. Antifungal compounds are hypothesized to be involved in the orchid’s ability to resist fungal development [27].

5. DISEASE PROFILE OF A. ODORATA

The wet season is when southern blight is most prone to occur. The base of the leaf is loaded with white mycelium during the start of the disease. The cause of southern blight is root rot. Farmers removed the fungal-infested soil, and use pentachloronitrobenzene powder or lime for the prevention and management of illness. The treatment approach has taken care to provide minimal air and light, as well as efficient basin drainage. Anthrax, on the other hand, is present all year and is most common, particularly in orchids. The spots appear are brown at first, then progressively develop and multiply, leaving many black spots, and eventually killing A. odorata all over in critical situations. The addition of 50% methyl tobujin powder wettable 800–1500 times for spray treatment, followed by the addition of 1% Bordeaux solution, sprayed continuously 3–5 times, has a significant impact on the effectiveness of preventative and control measures [28,29].

6. BROAD BIOLOGICAL ACTIVITY OF A. ODORATA

6.1. Antimicrobial Activity

Combining ancient expertise with cutting-edge research will aid in the development of new treatments that are more effective than synthetic drugs. A. odorata, have proven antibacterial activity against various bacterial species, according to the current study papers. Many natural compounds, such as pigments, enzymes, and bioactive chemicals, have been observed to dissolve in water, resulting in a considerably higher extraction yield. The concentrations of dissolving phytoconstituents vary depending on the solvent. The findings indicate that all three orchid species had excellent antibacterial activity against the three Escherichia coli strains studied [30]. Extractions of three different species of medicinal orchid plants, namely, Acampe papillosa, A. odorata, and Pholidota pallida, were carried out using ethanol, chloroform, petroleum ether, and methanolic extracts, respectively. These extracts were then tested for their ability to inhibit the growth of five different bacterial strains, namely, Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Salmonella typhi (Vibrio). Three extracts had antibacterial action against all of the species tested, including A. odorata Lour. and P. pallida Lindl. This activity was broad-spectrum in nature, which shown a significant amount of antibacterial activity [31]. In tests against Candida albicans, A. odorata demonstrated effective antifungal activity, with an inhibition zone measuring 14 mm. Methanolic extract of A. odorata demonstrated extremely considerable cytotoxicity in vitro against MCF-7 cell lines, and it was discovered to decrease more cell growth than HeLa cell line extract did [32].

6.2. Antioxidant Activity

Methanolic extracts of A. odorata stems and leaves were examined for full polyphenol, flavonoid, and antioxidant activity. Antioxidant activity was measured using 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH). In biological systems, free radicals are constantly being produced as a consequence of a variety of endogenous (such as normal cellular metabolism) or exogenous (such as irradiation) activities [33]. A significant amount of phenols and flavonoids may be obtained by processing the stem of the A. odorata plant. The flavonoids, reducing power, and radical scavenging assays were used to determine the degree, to which the various plant sections contributed to the overall antioxidant activity of the plant. The present study found that micro propagated plantlets had higher levels of antioxidant activity, and this was confirmed by the simultaneous estimation of phenolic acids and flavonoids in the various parts of the plant. This was accomplished with the assistance of a reversed phase high pressure liquid chromatography system that utilized a photodiode array detector and gradient elution [15]. On the other hand, the leaf extract of in vitro regenerated plantlets of A. odorata had greater levels of phenolics and antioxidants than those found in the wild species. There is a possibility that the variances are the consequence of changes in the conditions of the media and the elements of the media, the inclusion of activated charcoal (which may have decreased hazardous chemicals), and differences in the meteorological circumstances (for the field grown plant). In addition, the study demonstrated that the basal medium may have a part to play in the process of elevating the levels of antioxidants found in plants [34]. The stem of the Aerides odoratum plant was shown to have a significant capacity for scavenging radicals. Due to this, it is possible that this species possesses significant levels of antioxidant activities; hence, more study work should be carried out in terms of the characterization and assessment of secondary metabolites.

6.3. Medicinal Activities of Metabolites

Dragendroff’s reagent has revealed a high alkaloid presence in A. odorata, When Hager’s reagent (H) was tested on A. odorata, the presence of alkaloids was found to be greater. Wagner’s reagent (W) was also used to examine the quality of alkaloids using A. odorata. demonstrated on the quality of Tannin, Terpinoids, Steroids, Quinine, and Cumarin which revealed that A. odorata found the most potent orchid therapeutics [10]. Anti-cancer action has been found in A. odorata phytocompounds such as Xanthorrhizol [2-Methyl-5- (1,2,2-Trimethy cyclopentyl)] phenol. It has anticancer, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antihypertensive properties. The methyl ester of 9,12,15-octadecatrienoic acid has been demonstrated to have anticancer, hypocholesterolemic, antibacterial, and antioxidant properties. In addition to the chemicals mentioned, such as Phenyl (piperidin-3-yl) methanone, (E)-5-Methylundec-4-ene, 2-O-(2-Ethylhexyl)1-O- pentadecyl oxalate, and squalene Ethyl-D-glucopyranoside, Methyl (2E) - 3-phenyl - 2-propeonate 3,7,11-trimethyl-1,6,10-dodecatrien-3-ol (2E,6E)-3,7,11-trimethyldodeca-2,6,10-trien-1-ol is also shown anticancer activities. Squalene has anticancer properties and functions as a preventive agent against various diseases that affect humans and animals. 1,3 propanediol, for example, has an inclusive choice of applications. It is used as an adhesive, grease, antifreeze, and medication, among other things. Hexadecan-1-ol is an oily alcohol that is commonly used in skin creams and lotions as an emulsifier [5].

A. odorata Lour’s therapeutic characteristics include anticancer effects. Epilepsy, pneumonia, dyspepsia, paralysis, inflammation, hip, and fractures are all treated with it. A. odorata is thought to be utilized to alleviate joint discomfort, inflammation, tuberculosis (TB), and wound healing, according to the literature [10]. A. odorata is used ethnobotanically to cure a variety of maladies in different parts of the world, including chest and abdominal pain, skin disorders, TB, cuts and wounds, ear and nose abscesses, pneumonia, inflammation, and so on. The natural phytochemical structure of these ethnomedicinal plants is responsible for many of their pharmacological actions. The phytochemical investigation of A. odorata could lead to new bioactive chemical compounds [11]. A. odorata (leaf) can be used to treat TB [35], rheumatoid arthritis (root, combined with Azadirachta indica bark and Saracaasoca root), wounds (leaf), and abscesses [35]. The anticancer investigation found that increasing the amount of filter A. odorata leaf extract enhances the death rate of MCF-7 and HeLa cell lines. Non-toxic plant extracts with an IC50 more than 1000 g/ml are not hazardous, whereas toxic plant extracts with an IC50 <1000 g/ml are poisonous. Methanolic leaf extraction found the lowest quantity of IC50 26.211 g/ml in MCF-7 cell lines. It reveals that methanol emission has a strong inhibitory effect [5] [Figure 3]. Other extracts of orchids, such as those from the leaves of A. odorata, have been shown to be beneficial against breast cancer (MCF-7). It is postulated that the synergistic effect of the phytoconstituents that are present in these species is the cause of the cytotoxic activity. Epilepsy, influenza, dyspepsia, paralysis, inflammation, waist discomfort, and fractures are only some of the conditions that can be treated with the A. odorata leaf. In addition, it is utilized in the treatment of wounds, TB, swollen joints, and discomfort in the joints [36].

7. NEED, CHALLENGES, AND FUTURE OUTLOOK

The emergence of a defined seed quality is far from over, and there is an exciting development in the works to meet the market’s shifting needs. Hybrid seed production necessitates a certain set of circumstances, both in terms of skilled labor and agricultural settings. The seasonal variances between male and female maize seeds, for example, necessitate specialized climatic circumstances; hybrid vegetable cultivation necessitates low-cost skilled labor. Flowers, sprays, and natural components are produced from a variety of common orchid species. Growing additional orchids for testing and testing are a big problem for these investigations. Both crops are slow to develop and costly. Fungi and bacteria are the main causes of orchid illnesses. Leaf spots, flowers in bloom, and root, stem, and pseudobulb rots, which are all very sensitive, are the ones to look out for. Orchids provide conservation issues due to their complex biology, particularly their interactions with pathogenic and nonpathogenic bacteria, and this is compounded by unsustainable and often illegal collections in agriculture, medicine, food, and climate change [4]. In the last 5–10 years, however, no substantial critical assessments have been written on this issue. Due to declining wildlife numbers and rising demand for natural chemical stocks, wild collections are becoming increasingly rare; there are no books available on natural chemicals produced by cooperative cultures; the relationship between the host plant and its endophytic fungi is still unknown; natural compounds synthesis path is still unknown.

The A. odorata is one of the most financially complex orchid plant. The evolutionary relationships given here serve as a foundation for further systematic and taxonomic research on the Indian subcontinent. This investigation discovered some unexpected correlations, and the possible morphological synapomorphies of these relationships are unknown. To establish robust phylogenetic theories for the subtribe, more phylogenetic study using several cell markers and a large sample of tissue is necessary [37]. As natural producers of the metabolite, Orchidaceae fungal endophytes (OFEs) offer many future biotechnological opportunities and should be addressed when developing future plans to conserve endangered Aerides. Through the employment of biotechnological technologies focusing on the Aerides variety in the near future, OFEs can be identified as a valuable source of natural metabolites. Fungal elicitors produced from Orchidaceae-fungal endophytes could be exploited as a stimulant in A. odorata in vitro propagation in the future, and most of these identified natural chemicals could be evaluated for their effects on Aerides growth. Novel and new potential fungal endophytes and their active natural elements will provide a new dimension of understanding the role and function of endophytes and their elicitors in plant structure and products for industrial and pharmaceutical applications as advanced biotechnological advances are made. Aerides with their own microbiome structure could be a future trend. The biomarker for these microbiome chemicals should be biodiversity. The activity of natural regulators that affect the microbiome, as well as the utilization of microbial consortia, can be used to produce the many features associated with Aerides. Natural consortia-specific vegetation can be pooled with selected biocontrol experts in this case [38-43].

8. CONCLUSIONS

Finally, recent breakthroughs in conservation biology through biotechnological technologies have opened up opportunities to safeguard A. odorata biodiversity, but there has been little attempt to grow commercially accessible odorata, putting extra pressure on it. As a result, in addition to encouraging artificial insemination, the collecting of A. odorata from the wild should be restricted at all levels, and public awareness should be raised to ensure effective preservation. A biotechnological approach for A. odorata was developed, promising a future anticancer and antioxidant product. A better A. odorata in vitro distribution protocol could result in high-quality pharmaceutical building materials. The significance of their role in the economy is more known than the contribution that they provide to medicine. Research on the Aerides plant has made significant strides in the recent past; nevertheless, the therapeutic potential of A. odorata has not been thoroughly investigated. In terms of its phytochemistry, A. odorata has been shown to possess alkaloids and other naturally occurring chemicals with a wide variety of antibacterial, antioxidant, and anticancer activities.

9. ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are grateful to the Mansarovar Global University, Sehore, Madhya Pradesh, India and CES Analytical and Research Services India Pvt. Ltd. (Formerly known as Creative Enviro Services), Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, and India for their support and cooperation. We are also thankful to our laboratory colleagues and research staff members for their constructive advice and help.

10. AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All the authors are eligible to be an author as per the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) requirements/guidelines.

11. FUNDING

There is no specific funding received from any agency for this review article.

12. CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no financial or any other conflicts of interest in this work.

13. ETHICAL APPROVALS

Essentially this study does not require any ethical approval.

14. DATA AVAILABILITY

The data will be provided and made available as per the genuine interest and as per the journal policy.

15. PUBLISHER’S NOTE

This journal remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliation.

REFERENCES

1. Kocyan A, Vogel EF, Conti E, Gravendeel B. Molecular phylogeny of

2. Sopalun K, Iamtham S. Isolation and screening of extracellular enzymatic activity of endophytic fungi isolated from Thai orchids. S Afr J Bot 2020;134:273-9. [CrossRef]

3. Govinda RM, Suryanarayanan TS, Tangjang S. Endophytic fungi of orchids of Arunachal Pradesh, North Eastern India. Curr Res Environ Appl Mycol 2016;6:293-9. [CrossRef]

4. Sarsaiya S, Shi J, Chen J. Bioengineering tools for the production of pharmaceuticals:Current perspective and future outlook. Bioengineered 2019;10:469-92. [CrossRef]

5. Katta J, Rampilla V, Khasim SM. A Study on phytochemical and anticancer activities of epiphytic Orchid

6. Paudel M, Pradhan S Pant B.

7. Al-Faruque MA, Sultana KS, Rahman MA, Ghose AK, Al-Amin HM. Variabilities, correlation and morphological characteristics of different local orchids. Ecofriendly Agril J 2015;8:62-6.

8. Medhi RP, Chakrabarti S. Traditional knowledge of NE people on conservation of wild orchids. Indian J Tradit Knowl 2009;8:11-6.

9. Sivanaswari C, Thohirah LA, Fadelah AA, Abdullah NA. Hybridization of several Aerides species and

10. Akter M, Huda MK, Hoque MM. Investigation of secondary metabolites of nine medicinally important orchids of Bangladesh. J Pharmacogn Phytochem 2018;7:602-6.

11. Hartini S, Aprilianti P. Orchid exploration in Tanjung Peropa wildlife reserves for kendari botanic gardens collection, Indonesia 2020;21:2244-50. [CrossRef]

12. Parveen I, Singh HK, Malik S, Raghuvanshi S, Babbar SB. Evaluating five different loci (rbcL, rpoB, rpoC1, matK, and ITS) for DNA barcoding of Indian orchids. Genome 2017;60:665-71. [CrossRef]

13. Trimanto SA. Diversity of Epiphytic Orchids, Hoya,

14. Yonzone R, Bhujel RB, Rai S. Genetic resources, current ecological status and altitude wise distribution of medicinal plants diversity of Darjeeling Himalaya of West Bengal, India. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2012;S439-45. [CrossRef]

15. Prasad G, Mao AA, Vijayan D, Mandal S, Chaudhuri K, Seal T. Comparative HPLC fingerprinting and antioxidant activities of

16. Sangmaand LB, Chaurasiya AK. Indigenous orchids and zingiberaceous taxa of Garo Hills, Meghalaya. J Indian Bot Soc 2021;101:66-7. [CrossRef]

17. Jyoti TL. An account of epiphytic orchids of nainital in relation to their host specificity. J Biol Chem Chron 2020;6:1-4. [CrossRef]

18. Carlsward BS, Whitten WM, Williams NH, Bytebier B. Molecular phylogenetics of vandeae (

19. Sarmah D, Kolukunde S, Sutradhar M, Singh BK, Mandal T, Mandal N. A review on:

20. Final Report. National Agricultural Innovation Project (Indian Council of Agricultural Research) A Value Chain on Selected Aromatic Plants of North East India. Vol. 18. College of Agricultural Engineering and Post Harvest Technology Ranipool, Sikkim February;2014. Available from:https://naip.icar.gov.in/download/79347/207301.pdf/207301.pdf [Last accessed on 2022 Jan 31].

21. Jitsopakul N, Chunthaworn A, Pongket U, Thammasiri K. Interspecific and intergeneric hybrids of

22. Hartati S, Nandariyah YA, Djoar DW. Hybridization technique of black orchid (

23. Hasnu S, Deka K, Saikia D, Lahkar L, Tanti B. Morpho-taxonomical and phytochemical analysis of

24. Devi HS, Devi SI, Singh TD. High frequency plant regeneration system of

25. Grabka R, d'Entremont TW, Adams SJ, Walker AK, Tanney JB, Abbasi PA,

26. Manoharachary C. Orchids mycorrhizae. J Orchid Soc India 2019;33:23-9.

27. Pant B. Medicinal orchids and their uses:Tissue culture a potential alternative for conservation. Afr J Pelant Sci 2013;7:448-67. [CrossRef]

28. Smitamana P, McGovern RJ. Diseases of orchid. In:McGovern R, Elmer W, editors. Handbook of Florists'Crops Diseases, Handbook of Plant Disease Management. Cham:Springer;2018. 633-62. [CrossRef]

29. Maggie. Aerides Odorata Profile;2021. Available from:https://www.rayagarden.com/garden-plants/aerides-odorata-profile.html [Last accessed on 2022 Jan 31].

30. Paul P, Chowdhury A, Nath D, Bhattacharjee MK. Antimicrobial efficacy of orchid extracts as potential inhibitors of antibiotic resistant strains of

31. Hoque MM, Khaleda L, Al-Forkan M. Evaluation of pharmaceutical properties on microbial activities of some important medicinal orchids of Bangladesh. J Pharmacogn Phytochem 2016;5:265-9.

32. Lalrosangpuii, Lalrokimi. A review on the phytochemical properties of five selected genera of orchids. Sci Vision 2021;2:50-8. [CrossRef]

33. Rahman M, Huda MK. Exploration of phytochemical, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory efficacy of the ethnomedicinal uses of ten orchids of Bangladesh. Adv Med Plant Res 2021;9:30-9.

34. Onyeulo QN, Okafor CU, Okezie CEA. Antioxidant capabilities of three varieties of

35. Nurfadilah S. Utilization of orchids of Wallacea Region and implication for conservation. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2020;473:012063. [CrossRef]

36. ?liwi?ski T, Kowalczyk T, Sitarek P, Kolanowska M. Orchidaceae derived anticancer agents:A review. Cancers 2022;14:754. [CrossRef]

37. Hidayat T, Weston PH, Yukawa T, Ito M, Rice R. Phylogeny of subtribe

38. Jain A, Sarsaiya S, Chen J, Wu Q, Lu Y, Shi J. Changes in global Orchidaceae disease geographical research trends:Recent incidences, distributions, treatment, and challenges. Bioengineered 2021;12:13-29. [CrossRef]

39. Bhatti SK, Verma J, Sembi JK, Pathak P. Symbiotic seed germination of

40. Adit A, Singh VK, Koul M and Tandon R. Breeding system and response of the pollinator to floral larceny and florivory define the reproductive success in

41. Gogoi K. An annotated checklist of orchids of Dhemaji district of Assam (India) with an addition of one rare orchid for the flora of Assam. Richardiana 2022;6:55-72.

42. Ramasoot S, Weerapong M, Keawsaard Y, Ritchuay S, Rotduang P. Enhance efficiency propagation and conservation of toothbrush orchid

43. Adit A, Koul M, Kapoor R, Tandon R. Topological analysis of orchid-fungal endophyte interaction shows lack of phylogenetic preference. S Afr J Bot 2022;149:339-46. [CrossRef]