1. INTRODUCTION

Antibiotics gained worldwide acclaim after the discovery of penicillin in 1941, revolutionizing the treatment of bacterial infections in humans and other animals. Antibiotics are effective against a variety of pathogens depending on their mode of action but their overuse, and prolonged exposure has encouraged the selection and replication of antibiotic-resistant microbial strains in the decades thereafter [1,2]. In due course of time, majority of infection causing microorganisms have developed resistance to most of the antibiotics they were once susceptible to. This is of great concern as more and more strains of microorganisms have become antibiotic resistant, and some have developed resistant to several different antibiotics and therapeutic agents, the phenomenon named as multidrug resistance (MDR). According to the WHO list of antibiotic-resistant “priority pathogens,” there are 12 families of bacteria that pose the highest risk to human health, Acinetobacter baumannii (carbapenem-resistant), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (carbapenem-resistant), Enterobacteriaceae (carbapenem-resistant), Enterococcus faecium (vancomycin-resistant), Staphylococcus aureus (methicillin-resistant), Helicobacter pylori (clarithromycin-resistant), Campylobacter spp., (fluoroquinolone-resistant), Salmonellae (fluoroquinolone-resistant), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (cephalosporin-resistant, fluoroquinolone-resistant) Streptococcus pneumoniae (penicillin-resistant), Haemophilus influenzae (ampicillin-resistant), and Shigella spp., (fluoroquinolone-resistant) [3]. In fact, virtually all major bacterial infections in the world are becoming resistant to the antibiotics of choice. According to the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, antibiotic-resistant is estimated to cause 2.8 million deaths in the United States each year [4]. About 70% of the bacteria that cause these infections are resistant to at least one of the widely used antibiotics to treat these infections. Alternative strategies to combat multidrug resistance are thus required to prevent multidrug resistance from spreading further. Bacteriocins offer an alternative to the conventional antibiotics. They possess great potential to substitute antibiotics against multidrug-resistant pathogens [5]. Bacteriocins are proteinaceous compounds with molecular weights ranging from 2 to 30 kDa. These are ribosomally synthesized, bactericidal active proteins released extracellularly by Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Unlike antibiotics, which have a broad spectrum of activity, bacteriocins are limited in their antibacterial action to strains of closely related or same species. Bacteriocins do not kill the bacteria that produce them due to unique self-immunity proteins that form a strong complex with the receptor proteins and the bacteriocin, thereby avoiding cell death [6]. Bacteriocins have been given the Generally Recognized as Safe designation by the US Food and Drug Administration, implying that they are safe for human consumption under the conditions of their type and usage.

Nisin and pediocin PA-1 are the most well-studied bacteriocins derived from lactic acid bacteria (LAB) that have been utilized effectively as food preservatives. Despite having the status of Qualified Presumption of Safety, they have a number of limitations, including vulnerability to proteolytic enzymes, a limited antibacterial spectrum, a high dosage requirement, and poor yield [7,8]. Different studies have recently been conducted to overcome these limitations of bacteriocins and to achieve improved antibacterial spectrum, stability, and shelf life [8-11]. This review focuses on the latest advances and developments carried out for enhancing and broadening the antibacterial properties of bacteriocins to combat antibiotic resistance and their high efficacy in food and health-care applications.

2. PROPERTIES OF BACTERIOCINS

Bacteriocins are used in a variety of sectors as they are colorless, odorless, and tasteless, and also have excellent high thermal and pH tolerance. Because of their proteinaceous composition, proteolytic enzymes destroy them rapidly. As a result, they do not last long in the human body, hence, lowering the chances of antibiotic fragments interacting with target strains [12]. Furthermore, because they are ribosomally produced proteins, it is possible to improve their properties to augment their activity and spectrum of action. Bacteriocins generated by Gram-positive bacteria, particularly LAB, are of special interest due to their widespread industrial use. LAB bacteria are Gram-positive, facultative anaerobes that have a coccus or rod shape and are commonly found in fermented foods and dairy products. They often produce low molecular weight bacteriocins which are susceptible to gastrointestinal tract proteases and undergo post-translational modifications. These have been reported to demonstrate antimicrobial activity against S. aureus, Bacillus cereus, Clostridium botulinum, and Listeria monocytogenes [13,14]. Bacteriocins are favored against conventional antibiotics as they are completely digested in the body, hence, are safe; they are 103 to 106 times more potent, and they are resistant to thermal treatments such as pasteurization or sterilization [15].

3. BACTERIOCIN CLASSIFICATION

Bacteriocins are classified according to their basic structures, molecular weights, post-translational modifications, and genetic features. Based on these properties, they are divided into three categories [12]:

3.1. Class I Bacteriocin

Class I bacteriocins, commonly known as lantibiotics, are produced by Gram-positive bacteria such as LAB, Bacillus, Enterococcus, Streptococcus, Micrococcus, Staphylococcus, and actinomycetes. They are composed of 19–50 amino acids which undergo extensive post-translational modification to produce unique amino acids such as lanthionine, β-methyllanthionine, and dehydrobutyrine. The numerous rings formed by these unique amino acids provide them structural stability against high temperatures, wide pH ranges, and proteolysis. Class I bacteriocins are further divided into three subclasses, i.e. Ia (lantibiotics), Ib (labyrinthopeptins), and Ic (sanctibiotics). The most common and studied lantibiotic are nisins (major nisin variants include nisin A, nisin Q, and nisin Z) which are produced by LAB such as Lactobacillus lactis and are used as a food preservative [16].

3.2. Class II Bacteriocins

Class II bacteriocins are small heat stable peptides produced by LAB. Unlike Class I bacteriocins, Class II bacteriocins do not undergo post-translational modification. Class II bacteriocins are divided into four groups: Class IIa (pediocin-like peptides), Class IIb (unmodified two-peptide peptides), Class IIc (cyclic peptides with N and C terminals joined by a peptide bond), and Class IId (single peptide, linear, unmodified, and non-pediocin-like). Pediocin-like bacteriocins are the most prevalent Class IIa bacteriocins. Bactofencin A belongs to the bacteriocin Class IId and possesses numerous unique characteristics. It is highly cationic and resembles antibacterial cationic peptides found in eukaryotes [17]. Another notable feature of bactofencin A is that it has dltB homologue-mediated immunity, which unlike specific immunity proteins, is suggested to reduce the negative charge of the cell wall, preventing bacteriocins from interacting with cells [18]. Acidocin B, produced by Lactobacillus acidophilus, is an example of a Class IIa bacteriocin [13].

3.3. Class III Bacteriocin

Class III bacteriocins are large and heat-labile bacteriocins with very limited information. The most common class III bacteriocin is colicin produced by Escherichia coli. Other than colicin, this class incudes helveticin M (produced by Lactobacillus crispatus), helveticin J (produced by Lactobacillus helveticus), and enterolysin A (produced by E. faecalis). Recently, helveticin M has been characterized and was found to exhibit antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria by disrupting and disordering the cell wall and outer membrane [19]. Some notable bacteriocins, their sources and targets are given in Table 1 [7,19-30].

Table 1: Different types of bacteriocins.

| Type of Bacteriocin | Example | Isolated from | Active against | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I (Modified; <5 kDa) | ||||

| Ia (lantibiotics or lanthipeptides) contain unusual amino acids such as lanthionine | Nisin | Lactobacillus lactis | Streptococcus suis, Staphylococcus aureus, Actinobacillus suis, Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae and Haemophilus parasuis | [7,20] |

| Nisin A | Lactobacillus lactis subsp. lactis | Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus intermedius, Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus dysgalactiae, Enterococcus faecalis and Escherichia coli | [20] | |

| Nisin, Lacticin 481, Lacticin 3147 | Lactococcus lactis | Listeria monocytogenes | [21] | |

| Lacticin 3147 | Lactobacillus lactis subsp. lactis DPC3147 | Streptococcus dysgalactiae M, Staphylococcus aureus 10 and Streptococcus uberis | [20] | |

| Macedocin ST91KM | Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. macedonicus ST91KM | Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus dysgalactiae, Streptococcus uberis, Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis | [20] | |

| Cytolysin | Enterococcus faecalis | Mammalian cells and Gram-positive bacteria | [22] | |

| Ib (labyrinthopeptins or head-to-tail cyclized peptides whose N- and C- terminals are linked by peptide bonds) | Carnocyclin A, AS-48; Garvicin ML | Carnobacterium maltaromaticum Lactococcus garvieae | Leuconostoc, Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Lactococcus, Enterococcus, Carnobacterium, Listeria Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Lactococcus, Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Listeria, Clostridium | [7,23] |

| Ic (sanctibiotics or sulfur-to-alpha-carbon containing peptides) | Subtilosin A | Bacillus subtilis | Enterococcus. faecalis, L. monocytogenes, P. gingivalis, K. rhizophila, Enterobacter aerogenes, Streptococcus pyogenes and Shigella sonnei | [7] |

| Thuricin CD; Thurincin H | Bacillus thuringiensis | Clostridium difficile | [7] | |

| Id [Linear azole (in) e-containing peptides or LAPs: contain combinations of heterocyclic rings of thiazole and (methyl) oxazole] | Streptolysin S | Streptococcus pyogenes | Staphylococcus aureus protoplasts Streptococcus faecalis protoplasts Bacillus megaterium protoplasts Escherichia coli spheroplasts | [7] |

| Microcin B17 | Escherichia coli | Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Pseudomonas and Klebsiella | [7] | |

| Micrococcin P1 | Staphylococcus equorum | Listeria monocytogenes | [21] | |

| Ie (Glycocins i.e., containing glycosylated residues) | Glycocin F | Lactobacillus plantarum | Bacillus subtilis, Enterococcus. Faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, Streptococcus pyogenes, Yersinia frederiksenii, | [7] |

| Enterocin F4-9 | Enterococcus faecium | Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus durans, Bacillus coagulans, Escherichia coli JM109 | [7] | |

| If (Lasso peptides: contain an amide bond between first amino acid in core peptide chain and a negatively charged residue at position+7 to+9, thus producing a ring like structure that embraces C-terminal linear part of the peptide) | Microcin J25 | Escherichia coli | Salmonella and Shigella species, and Escherichia coli | [7] |

| Capistruin | Burkholderia thailandensis | Burkholderia and Pseudomonas strains | [7] | |

| Lassomycin | LAB | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | [7] | |

| Class II (Unmodified; heat stable; <10 kDa) | ||||

| IIa (pediocin-like peptides) | Plantaricin 423 | Lactobacillus plantarum 423 | Food-borne pathogens such as Listeria monocytogenes (the deadliest bacteria for food poisoning), Bacillus cereus, Clostridium sporogenes, Entterococcus faecalis, Listeria spp., Staphylococcus spp., Clostridium perfringens | [24] |

| Mundticin ST4SA | Enterococcus mundtii ST4SA | Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Listeria monocytogenes | [24] | |

| Pediocin PA-1 | Pediococcus acidilactici | Listeria monocytogenes and Clostridium perfringens | [20,21] | |

| Pediocin PA-1 | Enterococcus faecium NCIM 5423 and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Acr2 | Listeria monocytogenes | [20] | |

| Pediocin 34 | Pediococcus pentosaceous 34 | Listeria monocytogenes | [20] | |

| Pediocin AcH | Lactobacillus plantarum | Listeria monocytogenes | [21] | |

| Lactococcin Q | Lactobacillus lactis QU 4 | Strains of Lactobacillus lactis only | [25] | |

| Lacticin Q | Lactobacillus lactis QU 5 | High antibacterial activity against a wide range of Gram-positive bacteria | [25] | |

| Lacticin Z | Lactobacillus lactis QU 14 | High antibacterial activity against a wide range of Gram-positive bacteria | [25] | |

| Leucocin A | Leuconostoc gelidum UAL187 | Listeria monocytogenes | [20] | |

| Leucocin K7 | Leuconostoc mensenteroides K7 | Listeria monocytogenes | [20] | |

| Leucocin B | Leuconostoc carnosum Ta11a | Listeria monocytogenes | [20] | |

| Lactococcin BZ | Lactobacillus lactis spp. (lactis BZ) | Listeria monocytogenes; Lactobacillus, Enterococcus, Leuconostocs, Listeria, Bacillus, Enterobacter, Escherichia, Rhodococcus, Salmonella, Yersinia, and Citrobacter spp. | [20,26] | |

| Carnobacteriocin BM1 (IIa) and Piscicolin 126 (IIa) | Carnobacterium maltaromaticum UAL307 | Escherichia coli DH5a, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 14207 and Salmonella typhimurium ATCC 23564 | [20] | |

| Sukacin | Lactobacillus sakei | Listeria monocytogenes | [20] | |

| Aureocin A70 | Staphylococcus aureus | Listeria monocytogenes | [20] | |

| Bacteriocins 7293A and 7293B | Weissella hellenica BCC 7239 | Psudomonas aeruginosa, Aeromonas hydrophila, Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli | [20] | |

| Enterocins A and B | Enterococcus faecium | Listeria monocytogenes | [21] | |

| Enterocin A | Lactobacillus lactis MG1614 | Listeria monocytogenes | [20] | |

| IIb (two-peptide bacteriocins) | Lactococcin G | Lactobacillus lactis | Lactococcus lactis strains | [7] |

| Thermophilin 13 | Streptococcus thermophilus | Streptococcus thermophilus, Enterococcus faecium, Listeria innocua, Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus carnosus | [7] | |

| Carnobacteriocin XY | Carnobacterium piscicola LV17B | - | [27] | |

| IIc (Leaderless bacteriocins; cyclic peptides with N and C terminals joined by a peptide bond) | Lactocyclicin Q (61 aa) | Lactococcus sp. strain QU 12 | High activity against a wide range of Gram-positive bacteria | [25] |

| Leucocyclicin Q (61 aa) | Leuconostoc mesenteroides TK41401 | High activity against a wide range of Gram-positive bacteria | [25] | |

| Enterocin L50 | Enterococcus faecium | Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium perfringens and Clostridium botulinum | [7] | |

| Garvicin KS | Lactococcus garvieae KS1546 | Acinetobacter baumannii and Staphylococcus aureus | [20] | |

| IId (single peptide, linear, unmodified, non-pediocin-like bacteriocins) | Lactococcin 972 | LAB | Closely related lactococci species | [7] |

| Lactococcin A | Strains of Lactobacillus lactis | Lactococci sp. | [28] | |

| Class III (Unmodified; heat labile; > 10 kDa) | ||||

| Class III | Helvecitin M | Lactobacillus crispatus | Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, and Enterobacter cloacae | [19] |

| Enterolysin A | LAB | Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Serratia marcescens, Klebsiella pneumoniae, MRSA | [7] | |

| Zoocin A | LAB | Other Streptococci | [7] | |

| Dysgalacticin | Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis strain W2580 | Streptococcus pyogenes | [7] | |

| Caseicin | Lactobacillus casei | Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus | [7] | |

| Helveticin J | Lactobacillus helveticus 481 | Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Enterobacter cloacae Gardnerella vaginalis, Streptococcus agalactia | [7] | |

| Linocin M18 | Brevibacterium linens | Listeria monocytogenes | [21,29] | |

| Bacteriocin CAMT2 | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens ZJHD3-06 | Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli and Vibrio parahaemolyticus | [20,30] | |

4. MODE OF ACTION

Both antibiotics and bacteriocins have similar mechanisms of action, which include disrupting cell wall formation, inhibiting DNA replication and protein synthesis, and disrupting cell membrane integrity [Figure 1].

| Figure 1: Modes of action of bacteriocins. [Click here to view] |

4.1. Disruption in Cell Wall Synthesis

One of the common modes of action of bacteriocins is disruption of cell wall synthesis. For example: Nisin A is a bacteriocin produced by L. lactis and exhibits strong antimicrobial activity through bacteriostatic as well as bactericidal actions. The N-terminal domain of nisin is reported to bind to lipid II, a membrane-bound cell wall precursor, and blocks cell wall synthesis while the C-terminal is implicated in pore formation in the membrane, eventually leading to cell death due to intercellular chemical leakage. As a result, nisin A is employed in both food and pharmaceutical industries [16].

4.2. Inhibition of DNA Gyrase

Another mode of action of bacteriocins is inhibition of DNA gyrase, a class of topoisomerase. For example: Microcin B17 bacteriocin produced by E. coli strains possesses antibacterial properties. It specifically targets bacterial DNA gyrase and stabilizes gyrase-DNA covalent complexes, causing double-strand breaks and cell death. Microcin B17 works in a similar way as quinolone antibiotics. However, due to its low solubility and the limits imposed by its non-essential protein transporter-based absorption, microcin B17 is ineffective, making it relatively easy for bacteria to acquire transport-based resistance. Limitations in developing microcin-based antibacterial drugs can be resolved with a thorough understanding of its production process [31].

4.3. Inhibition of Protein Synthesis

Colicins are bacteriocins that inhibit protein synthesis at various stages by their explicit 16S rRNase activity. RNase domain of colicin E3 has been reported to bind to the A site in the 70S ribosome, triggering the cleavage of 16S rRNA. Bacteriocins, such as E3-E6 colicins and DF13 cloacin, demonstrate development of rRNase at 16S [20].

4.4. Endonuclease Activity

Furthermore, some colicins have been shown to exhibit endonuclease activity, cutting a specific nucleic acid at a specific place, for example, colicins E2, E7, E8, and E9 cleave DNA; colicins E3, E4, and E6 and cloacin DF13 cleave rRNA; and colicins D and E5 cleave tRNA. The most attractive feature of colicins is their specificity and wide range of interactions [32,33].

4.5. Inhibition of Septum Formation

Bacteriocins such as lactococcin 972 and garvicin A exhibit antibacterial properties by inhibiting the septum formation [27]. Septum formation occurs when the membrane pinches inward during bacterial cell division; the cytoplasm is divided down the center of the cell, resulting in two daughter cells. The cell cycle and cell division are halted as a result, leading to a variety of secondary effects such as cell enlargement, membrane rupture, and lysis [34].

5. BENEFITS AND DRAWBACKS OF BACTERIOCINS

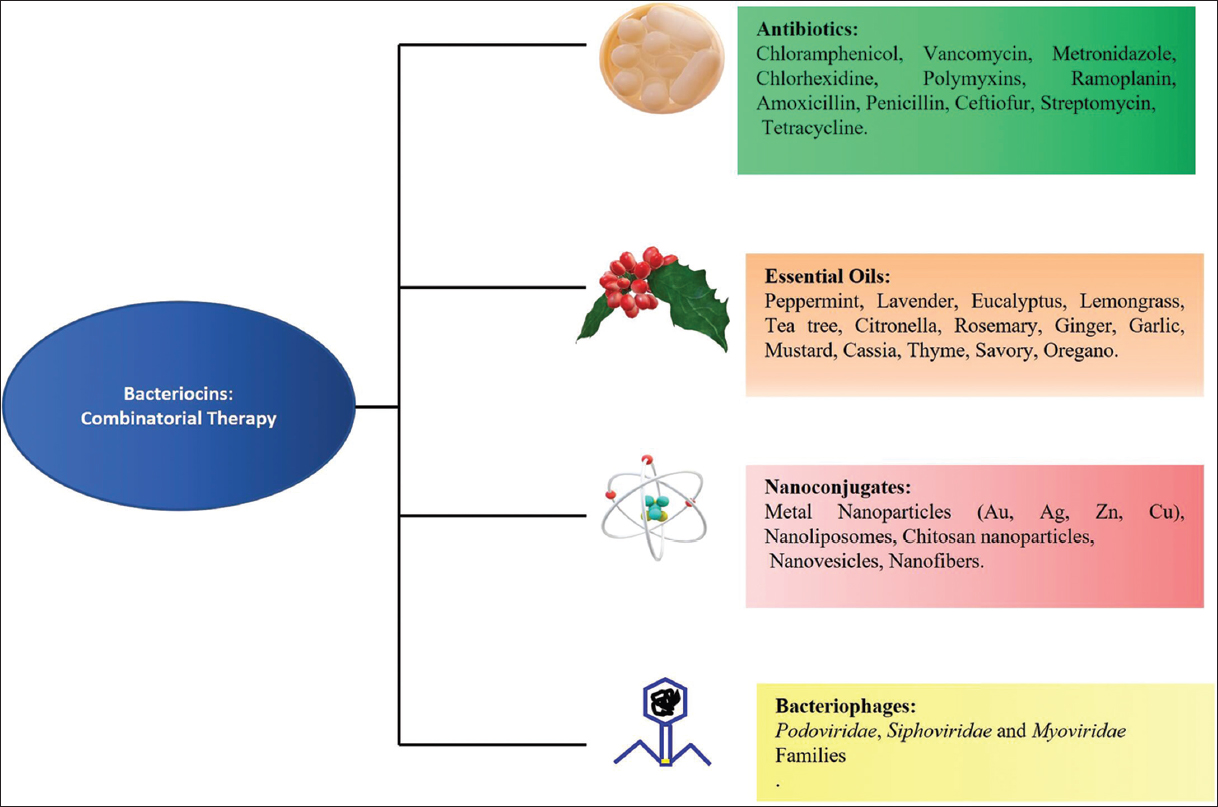

Bacteriocins have attracted a lot of attention in recent years as potential antibacterial agents due to a number of properties, including low toxicity to eukaryotic cells, low inhibitory concentrations against different bacterial strains (typically in the nanomolar range), and high temperature tolerance [13,35,36]. Although, bacteriocins are mostly employed as food preservatives in the food sector, they are increasingly gaining popularity as possible therapeutic antimicrobials and immune-modulating agents [37]. Although bacteriocins may offer a solution to the global problem of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, they have a number of drawbacks, including a limited antibacterial range, a high dose level for the suppression of multidrug-resistant bacteria, a high development cost, sensitivity to proteolytic enzymes, and a low yield due to insufficient purification recovery [8]. Furthermore, it has been observed that the usage of bacteriocins has resulted in the development of resistance in a variety of food spoilage and pathogenic bacteria [38,39]. It is a growing concern, especially in food industry, where bacteriocins are most frequently used. At present, there is limited information available on several aspects of bacteriocins including toxicity and immunogenicity. Various strains of Lactobacillus, Bacillus, Streptococcus, Listeria, Clostridium, and Staphylococcus have been found to have natural resistance to Class I bacteriocins [14]. Scientists are continuously seeking viable methods to counteract these drawbacks of bacteriocins. One of the most common approaches is combinatorial therapy, in which bacteriocins are coupled with other bioactive chemicals including antibiotics, nanoparticles (NPs), essential oils (EOs), and bacteriophages to enhance their antibacterial properties. Such combinations of bacteriocins have tremendous scope and potential to offer numerous benefits as they improve the antibacterial activity, stability, and solubility of bacteriocins while also protecting them from enzymatic degradation. Furthermore, one of the most significant advantages of these combinations is the reduced concentration of each component, which lowers their adverse effects. As a result, such combinations have a lot of potential in terms of expanding the usage of bacteriocins as antiviral and anticancer drugs.

6. COMBINATION THERAPY FOR BOOSTING BACTERIOCIN ACTIVITY

Scientists are continuously seeking viable methods to counteract various drawbacks of bacteriocins. One of the most common approaches is combinatorial therapy, in which bacteriocins are coupled with other bioactive chemicals including antibiotics, NPs, EOs, and bacteriophages to enhance their antibacterial properties [Figure 2]. Such combinations of bacteriocins have tremendous scope and potential to offer numerous benefits as they improve the antibacterial activity, stability, and solubility of bacteriocins while also protecting them from enzymatic degradation. Furthermore, one of the most significant advantages of these combinations is the reduced concentration of each component, which lowers their adverse effects. As a result, such combinations have a lot of potential in terms of expanding the usage of bacteriocins as antiviral and anticancer drugs. Numerous studies conducted using bacteriocins in combination with various bioactive compounds and proved to be effective against a variety of infections have been summarized in Table 2 [40-71].

| Figure 2: Bacteriocins combinatorial therapy: Combining bacteriocins with other antimicrobials with distinct modes of action, such as antibiotics, essential oils, nanoparticles, and bacteriophage, can boost antimicrobial efficacy while limiting the risk of resistance. [Click here to view] |

Table 2: Combination Therapy: Bacteriocins combined with other bioactive molecules.

| Combinations | Effective Against | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics and Bacteriocins | ||

| Nisin with ramoplanin | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains | [40] |

| Nisin with chloramphenicol | MRSA strains | [40] |

| Nisin with chloramphenicol or penicillin | E. faecalis | [41] |

| Nisin Z with methicillin | MRSA | [42] |

| Nisin, lysozyme and lactoferrin | Bovine viral diarrhea virus | [40] |

| Thuricin CD with ramoplanin | Clostridium difficile strains | [43] |

| Subtilosin A with metronidazole and metronidazole | Gardnerella vaginalis | [44] |

| PsVP-10 with chlorhexidine | Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus | [45] |

| Bacteriocin from L. plantarum ST8SH with Vancomycin | Biofilm of Listeria monocytogenes strains | [46] |

| Lacticin 3147 with penicillin G or vancomycin | Corynebacterium xerosis, Cutibacterium acnes, Enterococcus faecium and MRSA strains | [42] |

| Enterocin CRL35 and Subtilosin | Herpes simplex virus 1(HSV-1) and Poliovirus (PV-1) | [40] |

| Essential oils (EO) and bacteriocins | ||

| Nisin with carvacrol; Nisin with mountain savory | Increase relative sensitivity of Salmonella Typhimurium and Listeria monocytogenes to g-irradiation treatment | [47] |

| Nisin with Origanum vulgare EO | Listeria monocytogenes | [48] |

| Nisin with T. vulgaris EO | Salmonella typhimurium | [48] |

| Nisin with Ocimum basilicum EO, Salvia officinalis EO and Trachysper mumammi EO | Escherichia coli | [49] |

| Nisin V in combination with carvacrol and cinnamaldehyde | Listeria monocytogenes strains | [50] |

| Nisin with carvacrol (a component of EO of Origanum vulgare) and EDTA | Salmonella Typhimurium | [51] |

| Pediocin with S. montagna EO | Escherichia coli O157: H7 | [48] |

| Nanoparticle-bacteriocin conjugates | ||

| Nisin with nanoliposomes and garlic extract | Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella enteritidis, Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus Aureus | [52,53] |

| Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with nisin | Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus Aureus, Listeria monocytogenes | [9,54-56] |

| Ag NPs and nisin conjugates | Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Aspergillus niger, and Fusarium moniliforme | [57] |

| Nisin and Au NPs | Bacillus cereus, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus and Micrococcus luteus | [58] |

| Nisin and Alginate–chitosan nanoparticles | Listeria monocytogenes | [59] |

| Nisin and Phosphotidylcholine (PC) liposomes coated with chitosan or chondroitin | Listeria monocytogenes | [60] |

| Nisin and Soluble soybean polysaccharide-based NPs | Listeria monocytogenes, Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus | [61] |

| Subtilosin loaded poly (vinyl alcohol) (PVOH) nanofiber | Herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) | [62] |

| Iron oxide nanoparticles and nisin | Alicyclobacillus spp | [63] |

| Nisin in nanofibers | Listeria monocytogenes | [64] |

| Enterocin with Ag NPs | Bacillus cereus, Listeria monocytogenes | [65] |

| Pediocin and Au NPs with listeria adhesion protein | Listeria monocytogenes | [10] |

| Bacteriocin CAMT2 and nanovesicles made up of soybean phosphatidylcholine | Listeria monocytogenes | [66] |

| Bac4463 and Bac22 from Lactobacillus spp. With Ag NPs | Staphylococcus aureus and Sh. Flexneri | [8] |

| Plantaricin and Ag NPs | Listeria monocytogenes and other food-borne pathogens | [67] |

| Combined Bacteriocins and Bacteriophages | ||

| Coagulin C23 with bacteriophage FWLLm1 | Listeria monocytogenes | [68] |

| Enterocin AS-48 with bacteriophage P100 | Listeria monocytogenes | [69] |

| Bacteriocin produced by S. hyointestinalis B19 strain and bacteriophages P4 and A3 | Clostridium perfringens | [70] |

| Bacteriocin from Lactococcus lactis and bacteriophage SAP84 | Staphylococcus aureus | [71] |

6.1. Antibiotics and Bacteriocins

For decades, antibiotics have been widely used or misused. Antibiotic abuse has begun to restrict their efficacy as a result of the growth of multidrug-resistant and has resulted in emergence of plethora of deadly infectious diseases. Hence, it is imperative to develop different novel strategies to combat this worldwide problem. Using combination therapy, combining antibiotics with other antimicrobials like bacteriocins may allow antibiotics to be effective against these resistant bacteria [72,73]. The synergistic effect of these combinations enables these antimicrobial medicines to be used at much lower doses while still maintaining their efficacy [Table 2]. Combination of haloduracin and chloramphenicol has been reported to exhibit excellent synergy against a wide range of bacteria, including S. aureus, E. faecium, and several Streptococcus species [74]. Similarly, ramoplanin in combination with actagardine has been reported to exhibit a partial synergistic effect against 61.5 percent of target Clostridium difficile strains responsible for C. difficile associated diarrhea, frequently caused by disruptions in the intestinal microbiota caused by broad spectrum antibiotics [43]. Other lantibiotic actagardine-antibiotic combinations, such as vancomycin and metronidazole, have also been proven to be effective against various C. difficile strains [75]. Hanchi et al. (2017) [76] reported a synergistic effect of the bacteriocin durancin and vancomycin in the treatment of S. aureus, a bacterial human pathogen that has become increasingly difficult to treat due to the emergence of multi-drug resistant strains like methicillin-resistant S. aureus strains (MRSA). Durancin 61A and nisin bacteriocins have been shown to be effective against MRSA when used in combination with vancomycin/ramplanin [5]. Combining the bacteriocin PsVP-10 with the antibiotic chlorhexidine has been used to treat oral pathogens such as Streptococcus mutants and Streptococcus sobrinus [76]. E. faecalis, a hospital-acquired pathogen that causes infectious endocarditis, urinary tract infections, and other systemic infections has been found to be resistant to a wide range of antibiotic classes, including aminoglycosides, quinolones, macrolides, rifampicin, daptomycin, and β-lactams. In the presence of 200 U/ml nisin, the minimum inhibitory concentration and minimum bactericidal concentration of 18 different antibiotics against E. faecalis were observed to be reduced [40]. In addition, against three E. faecalis strains, synergistic interactions between and penicillin or chloramphenicol have been identified [75]. Bacteriocins like plantaricins have been demonstrated to have a synergistic effect with a range of antibiotics in the treatment of Candida albicans, the most common cause of fungal infections [77]. When used in combination with traditional antibiotics, bacteriocins (e.g., polymyxins and nisin) have been proven to be particularly effective in minimizing the development of biofilms formed by P. aeruginosa in the lungs of intensive care patients, even at extremely low doses [78]. This significant drop in concentrations has been attributed to nisin’s biofilm-penetrating potential, giving it a viable choice for the prevention of biofilm in medical devices and equipment. Similarly, using a combination of bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus plantarum ST8SH and nisin A with vancomycin has also been reported to prevent L. monocytogenes and multidrug-resistant S. aureus from forming biofilms [46,79]. Traditional antibiotics that were dying due to multidrug-resistant bacteria have been given new life by combinatorial therapies offered by bacteriocins and antibiotics. The synergistic effects of these combinations have great potential to eliminate key drawbacks and obstacles experienced in the treatment of infectious diseases by antibiotics alone, thereby changing the medical therapeutic paradigm.

6.2. EOs and Bacteriocins

The antimicrobial properties of EOs and their components have been recognized for a long time [80-82]. EOs are obtained by distilling various plant components and are formed of volatile molecules of a very complex combination (terpenes, flavonoids, phenolic acids, and aldehydes) produced as secondary metabolites of aromatic and medicinal plants. Only 300, of the almost 3000 EOs identified, are used commercially in food, perfume, pharmaceutical, and agriculture sectors, among others [83]. Antibacterial properties have been discovered in EOs such as peppermint, lavender, eucalyptus, lemongrass, and tea tree, among others, and they are being investigated as a natural alternative to chemical-based antimicrobials [81-84]. The production of strong odors and off-flavors is the two major drawbacks of employing EOs as antibacterial agents, restricting their use in large concentrations [85]. EOs can be used with other antibacterial drugs like bacteriocins to improve efficacy, reduce resistance, and minimize dosages. EOs from Rosmarinus officinalis, Origanum vulgare, Zingiber officinale, Cinnamomum cassia, Allium sativum, Brassica hirta, Thymus vulgaris, Satureja montagna, and Cymbopogon nardus, in combination with bacteriocins such as nisin and pediocin, have been reported to better control and inhibit a wide range of bacteria such as L. monocytogenes, B. cereus, Salmonella typhimurium, Aspergillus niger, E. coli, S. aureus, and Pseudomonas fluorescens [40,86-88]. The synergistic effect of combination of bacteriocin bacLP17 with EOs of T. vulgaris, Salvia officinalis has also been reported to effectively impair the biofilm produced by foodborne pathogen, L. monocytogenes [87]. Scanning electron microscopy examinations revealed higher damage to the cell wall and cell membrane when bacterial cells were treated with a combination of nisin and cinnamon EO than when treated with either of them alone [88]. When EOs and bacteriocins are used together, pores are formed in the bacterial cell membrane, resulting in altered membrane permeability, leakage of cellular components, and disruption of the pH gradient and membrane potential across the cell membrane, jeopardizing cellular metabolism and ultimately leading to cell death [40,85,89,90]. Hence, the combination of bacteriocins and EOs appears to be a promising and effective protective approach that warrants further investigation.

6.3. NP-Bacteriocin Conjugates

NPs have the potential to develop new materials in wide areas of applications such as energy, food, textiles, medical, and electronics [91-93]. NPs are ultrafine particles having a size of 1 to 100 nanometers with large surface area and other unique physicochemical properties. These properties of NPs are being exploited to overcome some of the limitations of traditional medicines and therapeutic agents [94-96]. Hence, their use is rapidly growing in medicine and pharmacology with exciting future prospects. Using NPs along with bacteriocins not only offers several benefits but also overcomes many different limitations of bacteriocins. NPs are reported to possess antibacterial properties, thus when combined with bacteriocin, they enhance the antimicrobial spectrum while also reducing the bacteriocin dose required [92]. NPs coat the bacteriocin molecules, preventing them from being degraded by proteolytic enzymes and allowing them to persist for longer periods of time. Bacteriocin-NP conjugates have been reported to possess improved efficacy against a variety of food-borne diseases as well as antibiotic-resistant bacteria [8]. According to Gomaa (2019) [96], bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus paracasei and silver NPs (AgNPs) conjugates have greater antibacterial activity against MDR pathogens such as S. aureus and Pseudomonas aeuroginosa due to increased cell membrane disruption, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and disrupted DNA replication and protein synthesis. Similarly, plantaricin, a bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus plantarum and coupled with AgNPs has shown to exhibit enhanced antibacterial activity against different foodborne pathogenic bacteria such as L. monocytogenes, Proteus mirabilis, E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, Salmonella Paratyphi A, Streptococcus faecalis, Shigella flexneri, and B. cereusi [67]. AgNPs-nisin, gold NPs (AuNPs)-nisin, and copper oxide NPs (CuONPs)-nisin conjugates are also known to display increased antibacterial properties against a large spectrum of pathogens like S. aureus, A. niger, E. coli, L. monocytogenes, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Micrococcus luteus, and Fusarium moniliforme [55,57,97]. Furthermore, other than metal oxide NPs, the nanocomposites like Ag-ZnO (AZO), chitosan NPs, nanoliposome encapsulated bacteriocins have also been reported to exhibit strong antibacterial activity against pathogenic and food spoiling bacteria [8,98]. Nanofibers, which are extremely fine threads with diameters in the nanometer range, due to large surface area and physical stability have been used as carriers and to encapsulate bacteriocins by electro-spinning them along with polymer solution [8,11]. For example, electro-spun nisin and nanofibers, used as wound dressing materials, have been shown to not only inhibit the growth of S. aureus strains over a prolonged period of time but also reduced the healing time [99]. Thus, combining bacteriocins with nanomaterials can not only have positive impact on their antibacterial properties and stability but can also overcome the ongoing problem of antibiotic resistance among bacteria.

6.4. Combined Bacteriocins and Bacteriophages

Bacteriophages are viruses that infect bacterial cells and employ a lytic or lysogenic cycle to generate viral components. Bacteriophages continue to multiply after infecting a bacterial population until the infected bacteria is destroyed, implying that only a low phage count delivered once is sufficient to kill the pathogenic bacteria. Recently, the combined use of bacteriocin-bacteriophage combinations has been reported to significantly reduce the target pathogens such as Clostridium perfringens, S. aureus, and L. monocytogenes [40,100]. Kim et al. (2019) [71] reported the synergistic inhibition of S. aureus by bacteriocin isolated from Lactococcus lactis and SAP84 bacteriophage. The combined use of Class II bacteriocin, coagulin C23 with FWLLm1 and FWLLm3 bacteriophages, and phage P100 with pediocin PA-1 showed enhanced synergistic effect against the foodborne pathogen, L. monocytogenes [101,102]. Bacteriocins and bacteriophage are easy to isolate and characterize since they are natural organisms. One drawback of using these natural antimicrobials is their narrow-spectrum since they are very precise in killing and, hence, the target bacterium must be identified before therapy can begin [103]. However, this problem will be overcome with the help of specially engineered phage cocktails. Bacteriocin and bacteriophage combinations have excellent prospects for improving food safety and quality without the use of potentially harmful chemical preservatives.

7. CHALLENGES AND FUTURE NEEDS

Bacteriocins are useful as alternative therapies in the treatment of infectious diseases because of their wide variety and abundance. In the recent decade, these powerful antimicrobials have been widely researched, resulting in a variety of uses including food preservation, medicinal therapies, and personal care. However, to fully realize their immense potential as antimicrobials, a number of challenges must be solved. Because bacteriocins are narrow spectrum antimicrobials, the target bacteria must be identified prior to therapy, and only that species will be attacked, leaving the remainder of the microbiota unharmed [104]. The demand for speedy, precise, and sensitive diagnostic tests for the detection of bacterial pathogens is the most significant challenge posed by bacteriocin’s selective property. Furthermore, this property of bacteriocins aids in lowering the selected resistance pressure of bystander microbes. When bacteriocin-based antimicrobial therapies are recommended for clinical use, it is critical to address the issue of resistance development. In vitro studies have contributed significantly to our understanding of the potential for bacteriocin resistance development [105]. Several bacteriocins (Class II bacteriocins, nisin, and other lantipeptides) have been shown to be non-cytotoxic on a variety of eukaryotic cell lines, even at extremely high concentrations, assisting in the treatment of infectious diseases. However, bacteriocins produced by virulence bacteria can also be used as virulence factors to increase pathogenicity by suppressing normal defense mechanisms [5]. As a result, all bacteriocins intended for human use must address cytotoxicity. Bacteriocins are a possible antibiotic alternative due to their tiny size, non-immunogenic nature, biocompatibility, and biodegradability. However, a number of challenges must be overcome before bacteriocin can be employed in medicine, including solubility, pH stability, purification, and large-scale manufacture. Bacteriocins have a complex molecular structure that includes post-translational changes, which makes large-scale replication problematic. The administrative route is another aspect that must be carefully researched and optimized. In terms of food particle size, digestive enzymes, salts, spices, bile, and other factors, the circumstances in the human gut are very varied, all of which cause variations in bacteriocin production. When administering bacteriocins orally, half-life in the gastrointestinal tract, intestinal absorption and bioavailability, pH stability, interaction with food particles and other microorganisms in the gut, resistance to digestive enzymes, and renal clearance are all factors to take into account.

8. CONCLUSION

Bacteriocins are antibacterial peptides capable of inhibiting both food spoilage and pathogenic bacteria, making them a potential alternative to antibiotics. Despite their many benefits, bacteriocins have significant drawbacks, such as restricted antimicrobial spectrum, high dosage requirement, increased sensitivity to proteolytic enzyme, high production costs, and a low yield due to ineffective purification processes. To overcome these limitations and improve the efficacy of bacteriocins, combinatorial use of bacteriocins with other antibacterial molecules and compounds provide the best solution. Combination therapies have proven to have a synergistic impact and are more effective than the antibacterial properties of individual components. Furthermore, these combinations enhance the antimicrobial spectrum, stability, solubility, and availability of bacteriocins. Such combinations have the potential to revolutionize the use of bacteriocins as antibacterial agents in food and health industries once their safety and efficacy are thoroughly evaluated in vitro and in vivo.

9. ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Poonam Sharma and Meena Yadav acknowledge Gargi College, and Maitreyi College, University of Delhi, Delhi, India, respectively, for providing infrastructural support.

10. AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All the authors are eligible to be an author as per the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) requirements/guidelines.

11. FUNDING

There is no funding to report.

12. CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

13. ETHICAL APPROVALS

This study does not involve experiments on animals or human subjects.

14. DATA AVAILABILITY

All data generated and analyzed are included within this research article.

15. PUBLISHER’S NOTE

This journal remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliation.

REFERENCES

1. Soltani S, Hammami R, Cotter PD, Rebuffat S, Said LB, Gaudreau H,

2. Dadgostar P. Antimicrobial resistance:Implications and costs. Infect Drug Resist 2019;12:3903-10. [CrossRef]

3. WHO;2017. Available from:https://www.who.int/news/item/27-02-2017-who-publishes-list-of-bacteria-for-which-new-antibiotics-are-urgently-needed

4. CDC;2019. Available from:https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/biggest-threats.html

5. Pircalabioru GG, Popa LI, Marutescu L, Gheorghe I, Popa M, Czobor Barbu I,

6. Duquesne S, Destoumieux-Garzón D, Peduzzi J, Rebuffat S. Microcins, gene-encoded antibacterial peptides from

7. Alvarez-Sieiro P, Montalbán-López M, Mu D, Kuipers OP. Bacteriocins of lactic acid bacteria:Extending the family. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2016;100:2939-51. [CrossRef]

8. Sidhu PK, Nehra K. Bacteriocin-capped silver nanoparticles for enhanced antimicrobial efficacy against food pathogens. IET Nanobiotechnol 2020;14:245-52. [CrossRef]

9. Cui HY, Wu J, Li CZ, Lin L. Anti-listeria effects of chitosan-coated nisin-silica liposome on Cheddar cheese. J Dairy Sci 2016;99:?-606. [CrossRef]

10. Singh AK, Bai X, Amalaradjou MA, Bhunia AK. Antilisterial and antibiofilm activities of Pediocinand LAP functionalized gold nanoparticles. Front Sustain Food Syst 2018;2:74. [CrossRef]

11. Sulthana R, Archer AC.

12. Negash AW, Tsehai BA. Current applications of bacteriocin. Int J Microbiol 2020;2020:4374891. [CrossRef]

13. Mokoena MP. Lactic acid bacteria and their bacteriocins:Classification, biosynthesis and applications against uropathogens:A mini-review. Molecules 2017;22:1255. [CrossRef]

14. Simons A, Alhanout K, Duval RE. Bacteriocins, antimicrobial peptides from bacterial origin:Overview of their biology and their impact against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Microorganisms 2020;8:639. [CrossRef]

15. Bédard F, Hammami R., Zirah S, Rebuffat S, Fliss I, Biron E. Synthesis, antimicrobial activity and conformational analysis of the class IIa bacteriocin pediocin PA-1 and analogs thereof. Sci Rep 2018;8:9029. [CrossRef]

16. Shin JM, Gwak JW, Kamarajan P, Fenno JC, Rickard AH, Kapila YL. Biomedical applications of nisin. J Appl Microbiol 2016;120:1449-65. [CrossRef]

17. O'Connor PM, O'Shea EF, Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. The potency of the broad spectrum bacteriocin, bactofencin A, against staphylococci is highly dependent on primary structure, N-terminal charge and disulphide formation. Sci Rep 2018;8:11833. [CrossRef]

18. O'Shea EF, O'Connor PM, O'Sullivan O, Cotter PD, Ross RP, Hill C. Bactofencin A, a new type of cationic bacteriocin with unusual immunity. mBio 2013;4:e00498-13. [CrossRef]

19. Sun Z, Wang X, Zhang X, Wu H, Zou Y, Li P,

20. Ng ZJ, Zarin MA, Lee CK, Tan JS. Application of bacteriocins in food preservation and infectious disease treatment for humans and livestock:A review. RSC Adv 2020;10:38937-64. [CrossRef]

21. Mounier J, Coton M, Irlinger F, Landaud S, Bonnarme P. Smear-ripened cheeses. In:Cheese, Chemistry, Physics and Microbiology. 4th ed. United States:Academic Press;2017. [CrossRef]

22. Rahman IR, Sanchez A, Tang W, van der Donk WA. Structure-activity relationships of the enterococcal cytolysin. ACS Infect Dis 2021;7:2445-54. [CrossRef]

23. Gabrielsen C, Brede DA, Nes IF, Diep DB. Circular bacteriocins:Biosynthesis and mode of action. Appl Environ Microbiol 2014;80:6854-62. [CrossRef]

24. Vermeulen RR, Van Staden AD, Dicks L. Heterologous expression of the class iia bacteriocins, plantaricin 423 and mundticin ST4SA, in

25. Zendo T. Screening and characterization of novel bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2013;77:893-9. [CrossRef]

26. ?ahingil D, ??lero?lu H, Y?ld?r?m Z, Akçelik M, Y?ld?r?m M. Characterization of lactococcin BZ produced by

27. Acedo JZ, Towle KM, Lohans CT, Miskolzie M, McKay RT, Doerksen TA,

28. Holo H, Nilssen O, Nes IF. Lactococcin A, a new bacteriocin from

29. Valdés-Stauber N, Scherer S. Isolation and characterization of Linocin M18, a bacteriocin produced by Brevibacterium linens. Appl Environ Microbiol 1994;60:3809-14. [CrossRef]

30. An J, Zhu W, Liu Y, Zhang X, Sun L, Hong P,

31. Collin F, Maxwell A. The microbial toxin microcin B17:Prospects for the development of new antibacterial agents. J Mol Biol 2019;431:3400-26. [CrossRef]

32. Cascales E, Buchanan SK, DuchéD, Kleanthous C, Lloubès R, Postle K,

33. Brown CL, Smith K, McCaughey L, Walker D. Colicin-like bacteriocins as novel therapeutic agents for the treatment of chronic biofilm-mediated infection. Biochem Soc Trans 2012;40:1549-52. [CrossRef]

34. Maldonado-Barragán A, Caballero-Guerrero B, Lucena-Padrós H, Ruiz-Barba JL. Induction of bacteriocin production by coculture is widespread among plantaricin-producing

35. Chikindas ML, Weeks R, Drider D, Chistyakov VA, Dicks LM. Functions and emerging applications of bacteriocins. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2018;49:23-8. [CrossRef]

36. Preciado GM, Michel MM, Villarreal-Morales SL, Flores-Gallegos AC, Aguirre-Joya J, Morlett-Chávez J,

37. Sahoo TK, Jena PK, Prajapati B, Gehlot L, Patel AK, Seshadri S.

38. do Carmo de Freire Bastos M, Coelho ML, da Silva Santos OC. Resistance to bacteriocins produced by Gram-positive bacteria. Microbiology (Reading, England) 2015;161:683-700. [CrossRef]

39. Kumariya R, Garsa AK, Rajput YS, Sood SK, Akhtar N, Patel S. Bacteriocins:Classification, synthesis, mechanism of action and resistance development in food spoilage causing bacteria. Microb Pathog 2019;128:171-7. [CrossRef]

40. Zgheib H, Drider D, Belguesmia Y. Broadening and enhancing bacteriocins activities by association with bioactive substances. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:7835. [CrossRef]

41. Tong Z, Zhang Y, Ling J, Ma J, Huang L, Zhang L. An

42. Ellis JC, Ross RP, Hill C. Nisin Z and lacticin 3147 improve efficacy of antibiotics against clinically significant bacteria. Fut Microbiol 2020;14:18. [CrossRef]

43. Mathur H, O'Connor PM, Hill C, Cotter PD, Ross RP. Analysis of anti-

44. Cavera VL, Volski A, Chikindas ML. The natural antimicrobial subtilosin a synergizes with lauramide arginine ethyl ester (LAE), e-Poly-L-lysine (polylysine), clindamycin phosphate and metronidazole, against the vaginal pathogen

45. Lobos O, Padilla A, Padilla C.

46. Todorov SD, de Paula OA, Camargo AC, Lopes DA, Nero LA. Combined effect of bacteriocin produced by

47. Ndoti-Nembe A, Vu KD, Doucet N, Lacroix M. Effect of combination of essential oils and bacteriocins on the efficacy of gamma radiation against

48. Turgis M, Vu KD, Dupont C, Lacroix M. Combined antimicrobial effect of essential oils and bacteriocins against foodborne pathogens and food spoilage bacteria. Food Res Int 2012;48:696-702. [CrossRef]

49. Mehdizadeh T, Hashemzadeh MS, Nazarizadeh A, Neyriz-Naghadehi M, Tat M, Ghalavand M,

50. Field D, Daly K, O'Connor PM, Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. Efficacies of nisin A and nisin V semipurified preparations alone and in combination with plant essential oils for controlling

51. Ay Z, Tuncer Y. Combined antimicrobial effect of Nisin, Carvacrol and EDTA against

52. Pinilla CM, Brandelli A. Antimicrobial activity of nanoliposomes co-encapsulating nisin and garlic extract against Grampositive and Gram-negative bacteria in milk. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol 2016;36:287-93. [CrossRef]

53. Zou Y, Lee HY, Seo YC, Ahn J. Enhanced antimicrobial activity of nisin-loaded liposomal nanoparticles against foodborne pathogens. J Food Sci 2012;77:M165-70. [CrossRef]

54. Alishahi A. Antibacterial effect of chitosan nanoparticle loaded with nisin for the prolonged effect. J Food Saf 2014;34:111-8. [CrossRef]

55. Naskar A, Kim KS. Potential novel food-related and biomedical applications of nanomaterials combined with bacteriocins. Pharmaceutics 2021;13:86. [CrossRef]

56. Zohri M, Alavidjeh MS, Haririan I, Ardestani MS, Ebrahimi SE, Sani HT,

57. Pandit R, Rai M, Santos CA. Enhanced antimicrobial activity of the food-protecting nisin peptide by bioconjugation with silver nanoparticles. Environ Chem Lett 2017;15:443-52. [CrossRef]

58. Thirumurugan A, Ramachandran S, ShiamalaGowri A. Combined effect of bacteriocin with gold nanoparticles against food spoiling bacteria-an approach for food packaging material preparation. Int Food Res J 2013;20:1909-12.

59. Zimet P, MombrúÁW, Faccio R, Brugnini G, Miraballes I, Rufo C,

60. da Silva IM, Boelter JF, da Silveira NP, Brandelli A. Phosphatidylcholine nanovesicles coated with chitosan or chondroitin sulfate as novel devices for bacteriocin delivery. J Nanoparticle Res 2014;16:2479. [CrossRef]

61. Luo L, Wu Y, Liu C, Huang L, Zou Y, Shen Y,

62. Torres NI, Noll KS, Xu S, Li J, Huang Q, Sinko PJ,

63. Song Z, Yuan Y, Niu C, Dai L, Wei J, Yue T. Iron oxide nanoparticles functionalized with nisin for rapid inhibition and separation of

64. Cui H, Wu J, Li C, Lin L. Improving anti-listeria activity of cheese packaging via nanofiber containing nisin-loaded nanoparticles. LWT Food Sci Technol 2017;81:233-42. [CrossRef]

65. Sharma TK, Sapra M, Chopra A, Sharma R, Patil SD, Malik RK,

66. Jiao D, Liu Y, Liu Y, Zeng R, Hou X, Nie G,

67. Amer SA, Abushady HM, Refay RM, Mailam MA. Enhancement of the antibacterial potential of plantaricin by incorporation into silver nanoparticles. J Genet Eng Biotechnol 2021;19:13. [CrossRef]

68. Rodríguez-Rubio L, García P, Rodríguez A, Billington C, Hudson JA, Martínez B. Listeriaphages and coagulin C23 act synergistically to kill

69. Baños A, García-López JD, Núñez C, Martínez-Bueno M, Maqueda M, Valdivia E. Biocontrol of

70. Heo S, Kim MG, Kwon M, Lee HS, Kim GB. Inhibition of

71. Kim SG, Lee YD, Park JH, Moon GS. Synergistic inhibition by bacteriocin and bacteriophage against

72. Montalbán-López M, Cebrián R, Galera R, Mingorance L, Martín-Platero AM, Valdivia E,

73. Kranjec C, Kristensen SS, Bartkiewicz KT, Brønner M, Cavanagh JP, Srikantam A,

74. Danesh A, Ljungh Å, Mattiasson B, Mamo G. Synergistic effect of haloduracin and chloramphenicol against clinically important Gram-positive bacteria. Biotechnol Rep (Amst) 2016;13:37-41. [CrossRef]

75. Mathur H, Field D, Rea MC, Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. Bacteriocin-antimicrobial synergy:A medical and food perspective. Front Microbiol 2017;8:1205. [CrossRef]

76. Hanchi H, Hammami R, Gingras H, Kourda R, Bergeron MG, Ben Hamida J,

77. Sharma A, Srivastava S. Anti-candida activity of two-peptide bacteriocins, plantaricins (Pln E/F and J/K) and their mode of action. Fungal Biol 2014;118:264-75. [CrossRef]

78. Field D, Seisling N, Cotter PD, Ross RP, Hill C. Synergistic nisin-polymyxin combinations for the control of

79. Angelopoulou A, Field D, Pérez-Ibarreche M, Warda AK, Hill C, Ross RP. Vancomycin and nisin A are effective against biofilms of multi-drug resistant

80. Abers M, Schroeder S, Goelz L, Sulser A, St Rose T, Puchalski K,

81. Man A, Santacroce L, Jacob R, Mare A, Man L. Antimicrobial activity of six essential oils against a group of human pathogens:A comparative study. Pathogens 2019;8:15. [CrossRef]

82. Tanhaeian A, Sekhavati MH, Moghaddam M. Antimicrobial activity of some plant essential oils and an antimicrobial-peptide against some clinically isolated pathogens. Chem Biol Technol Agric 2020;7:9. [CrossRef]

83. Ni ZJ, Wang X, Shen Y, Thakur K, Han J, Zhang JG,

84. Wi?ska K, M?czka W, ?yczko J, Grabarczyk M, Czubaszek A, Szumny A. Essential oils as antimicrobial agents-myth or real alternative?Molecules 2019;24:2130. [CrossRef]

85. Pietrysiak E, Smith S, Ganjyal GM. Food safety interventions to control

86. Bag A, Chattopadhyay RR. Synergistic antibacterial and antibiofilm efficacy of nisin in combination with p-coumaric acid against food-borne bacteria

87. Iseppi R, Camellini S, Sabia C, Messi P. Combined antimicrobial use of essential oils and bacteriocin bacLP17 as seafood biopreservative to control

88. Shi C, Zhang X, Zhao X, Meng R, Liu Z, Chen X,

89. Hao K, Xu B, Zhang G, Lv F, Wang Y, Ma M,

90. Yap PS, Yusoff K, Lim SE, Chong C, Lai K. Membrane disruption properties of essential oils-a double-edged sword?Processes 2021;9:595. [CrossRef]

91. Lugani Y, Sooch BS, Singh P, Kumar S. Nanobiotechnology applications in food sector and future innovations. Microbial Biotechnol Food Health 2021:197-225. [CrossRef]

92. Sharma P. Characterization and bacterial toxicity of titanium dioxide NPs. Int J Sci Res 2021;10:9-11. [CrossRef]

93. Sim S, Wong NK. Nanotechnology and its use in imaging and drug delivery (Review). Biomed Rep 2021;14:42. [CrossRef]

94. Cheng Z, Li M, Dey R, Chen Y. Nanomaterials for cancer therapy:Current progress and perspectives. J Hematol Oncol 2021;14:85. [CrossRef]

95. Gavas S, Quazi S, Karpi?ski TM. Nanoparticles for cancer therapy:Current progress and challenges. Nanoscale Res Lett 2021;16:173. [CrossRef]

96. Gomaa EZ. Synergistic antibacterial efficiency of bacteriocin and silver nanoparticles produced by probiotic

97. Mirhosseini M, Marvasti SH. Antibacterial activities of copper oxide (CuO) nanoparticles in combination with nisin and ultrasound against foodborne pathogens. Iran J Med Microbiol 2017;11:125-35.

98. Lee EH, Khan I, Oh DH. Evaluation of the efficacy of nisin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles against foodborne pathogens in orange juice. J Food Sci Technol 2018;55:1127-33. [CrossRef]

99. Fahim HA, Khairalla AS, El-Gendy AO. Nanotechnology:A valuable strategy to improve bacteriocin formulations. Front Microbiol 2016;7:1385. [CrossRef]

100. Walsh L, Johnson CN, Hill C, Ross RP. Efficacy of phage-and bacteriocin-based therapies in combatting nosocomial MRSA infections. Front Mol Biosci 2021;8:654038. [CrossRef]

101. Gutiérrez D, Fernández L, Rodríguez A, García P. Role of bacteriophages in the implementation of a sustainable dairy chain. Front Microbiol 2019;10:12. [CrossRef]

102. Komora N, Maciel C, Pinto CA, Ferreira V, Brandão T, Saraiva J,

103. Mills S, Ross RP, Hill C. Bacteriocins and bacteriophage;a narrow-minded approach to food and gut microbiology. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2017;41:S129-53. [CrossRef]

104. Melander RJ, Zurawski DV, Melander C. Narrow-spectrum antibacterial agents. Medchemcomm 2018;9:12-21. [CrossRef]

105. Cotter PD, Ross RP, Hill C. Bacteriocins-a viable alternative to antibiotics?Nat Rev Microbiol 2013;11:95-105. [CrossRef]