1. INTRODUCTION

Food allergy incidence appears to be increasing in some parts of the world.In the United States, around 6 million children suffer from food allergies, with peanut and tree nut allergy affecting about 1%–2% of children [1,2].Peanut and tree nut allergies are usually a life-long problem and can cause severe life-threatening reactions [3]. Food allergy is a Type I hypersensitivity mediated by immunoglobulin E (IgE) binding and basophil/mast cell degranulation. Oral immunotherapy treatment for food allergy may provide sustained unresponsiveness for some patients, but the mechanism by which this occurs is not fully understood [4]. Studies focused on early introduction of peanuts into children’s diets have strongly hinted at a developmental window that predisposes the immune system towards a tolerant response to potential food allergens [5,6].

Peanuts and tree nuts contain three conserved seed storage proteins that commonly act as food allergens. These include the peanut proteins Ara h 1–3 and the cashew proteins Ana o 1–3 [7]. These proteins (1) are resistant to proteolytic digestion, (2) in some cases are classified as plant defensive proteins, and (3) may have sequence homology to protease inhibitors. Ara h 2 from peanut and Ana o 3 from cashew are 2S albumins that are considered immuno-dominant allergens and are resistant to digestion. The 2S albumins are members of the prolamin superfamily with homology to cereal alpha-amylase and protease inhibitors that may provide some resistance to pests by inhibiting digestive enzymes [7,8]. 2S albumins from the Brassicaceae species have been shown to inhibit fungal growth. Similarly, allergenic 2S albumins from the castor bean have been shown to inhibit insect larvae α-amylases and growth, and a 2S albumin from black mustard seed was isolated as a trypsin inhibitor. Likewise, 2S albumins have been shown to survive digestion by human proteases [9]. These and other studies suggest 2S albumins may function to protect plants from consumption.

Processing steps, such as heating, meant to make peanuts and tree nuts more suitable for consumption may modulate the allergenic potency of the proteins and create Maillard reaction products [7,10–12]. Mechanical, physical, and enzymatic processing of nut allergens have been demonstrated to lower IgE binding to nut allergens. For example, protease treatment of peanuts and peanut flour reduced IgE binding to peanut allergens [13], and pepsin treated cashew proteins have reduced IgE binding [9,14].

Over millions of years, fungi and other microorganisms have evolved effective measures to utilize plant seeds and nuts for sustenance. They have developed adaptive measures to compete effectively against plant defenses and can alter gene expression to induce specialized enzymes for invasion and digestion of plant material. These specialized enzymes have evolved to counteract plant defenses and enable more efficient utilization of plant resources for fungal growth. Enzymes from fungal species are used in many industrial and pharmaceutical applications [15–17]. Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus oryzae have been used for many years in the food and biopharmaceutical industry and are included in the United States Food and Drug Administrations’ generally regarded as safe list. Similarly, the Food and Agricultural Organization and the World Health Organization routinely accept native and recombinant enzyme preparations from these fungi for food and other human use applications.

Aspergillus species are opportunistic plant and animal pathogens and have evolved unique mechanisms to adapt to and avoid host defenses and utilize hard to get/metabolize nutrient sources. Growth conditions can drastically affect gene transcription and the metabolic enzymes utilized for growth. For example, growth of Aspergillus species on various media has demonstrated upregulation of various proteases and other hydrolytic enzymes [11,18,19]. These enzymes may have several applications as food processing enzymes, dietary aids, or therapeutic targets. For example, a solution of alpha-galactosidase from A. niger, marketed as “Beano®,” has been shown to reduce flatulence as a dietary supplement [20]. Similarly, the “Flavourzyme” preparation contains several proteolytic enzymes from A. oryzae [21]. Analogously, transcriptional profiling of the filamentous fungi Trichophyton rubrum, the major agent of all chronic and recurrent dermatophytoses, grown on elastin and keratin identified a large number of proteases including subtilisins and aminopeptidases when T. rubrum was grown in the presence of keratin [22]. These proteases may be useful as therapeutic targets.

Previously, secreted A. niger proteins identified by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and mass-spectrometry were characterized when A. niger was cultured on media containing defatted cashew nut flour [11]. To widen the scope of this strategy, we performed whole transcriptome analysis of A. niger that was cultured on peanut and cashew nut-flour based media. The objective of this study was to identify genes upregulated in response to growth on nut flour media. Several highly upregulated genes were identified encoding proteins that may serve as (1) targets for fungal control on peanuts or tree nuts, (2) be useful as future food/food allergen processing enzymes, or (3) act as dietary aids to assist in digestion and nutrient uptake.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Materials

Defatted peanut flour from light (14 minutes at 125°C followed by 14 minutes at 161°C) and dark (14 minutes at 125°C followed by 14 minutes at 174°C) roasted peanuts were generously donated by The Golden Peanut Company (Alpharetta, GA). Defatted cashew flour from dark roasted cashew (DRC) nuts was generated as described in Mattison et al. [23].

2.2. Media Preparation

Media for this study was prepared by adding 10 g of defatted nut flour, 0.2 g MgSO4 • H2O, and 0.2 ml of micronutrient solution (containing 700 mg Na2B4O7 • 10H2O, 500 mg (NH4)6Mo7O24 • 4H2O, 10g Fe2(SO4)3 • 6H2O, 300 mg CuSO4 • 5H2O, 110 mg MnSO4 • H2O, and 1.76 g ZnSO4 • 7H2O in 1 l of water pH (5.2) to 100 ml of water and mixing for 1 hour. Control media containing 10 g of glucose instead of nut flour was used as a control media. Media were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 12,000 × g to remove particulates and then pulled through 0.45 μM filter by vacuum. The resulting nut flour media were judged to be approximately equivalent in total protein content as evaluated by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining.

2.3. Aspergillus niger Culture

Fungal cultures (A. niger, SRRC 0530) were grown essentially as described in [11] with the following modifications. Spores (approximately 106/ml) were transferred to 1 l glucose minimal salts (GMS) broth; per liter: glucose, 50 g; (NH4)2 SO4, 3g; KH2PO4, 10g; MgSO4 ·7H2O, 2g; 1 ml micronutrient solution; pH 5.2) in a 2 l baffled Erlenmeyer flask and incubated in the dark at 30°C, 200 rpm for 18 hours. Mycelia were collected by vacuum filtration through sterile miracloth and washed 1× with sterile deionized water. Mycelia (1 g) were transferred to 50 ml nut flour broths containing either dark roast peanut (DRP), light roast peanut (LRP), or DRC nut flour per 100 ml: 0.5 g defatted flour; 0.2 g MgSO4·H2O; 0.1 ml micronutrient solution; pH 5.2) and to 50 ml GMS broths in 250 ml Erlenmeyer flasks (3 flasks of each). One aliquot of the cashew flour broth remained un-inoculated as a control. Cultures were incubated in the dark at 30°C with agitation at 200 rpm for 24 hours. Mycelia were collected by vacuum filtration through sterile miracloth, flash frozen with liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Broths (10 ml) were collected from each sample for protein analysis.

2.4. RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq)

RNA-Seq was conducted using an Illumina HiSeq 2500 with 100 bp single end reads. Three biological replicates for each condition were sequenced across two sequencing lanes, providing an average of 19.5 million reads per replicate. Sequencing reads were mapped to the A. niger ATCC 1015 (assembly v4.0, http://genome.jgi.doe.gov/Aspni7/Aspni7.home.html) reference sequence using GSNAP (version 2017-0503) [24,25]. Reads mapping to exons were counted using “featureCounts” (version 1.5.2) [26], followed by differential expression testing with DESeq2 [27]. Genes were considered differentially expressed if they had at least an 8-fold change and an adjusted p-value < 0.01. Gene ontology term enrichment was done using the GOSeq R Bioconductor package. KEGG annotation was produced through the BlastKOALA [28] service. The raw sequencing data from the transcriptome project is available at NCBI under accession number PRJNA553205 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/study/?acc=PRJNA553205).

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. RNA-Seq Identifies Unique Gene Expression Profiles in Response to Nut-Flour Based Media

RNA-Seq was used to characterize changes in A. niger gene expression due to growth on media containing peanut or cashew nut flour or a standard glucose control media. Reads were mapped to the A. niger ATCC 1015 reference genome and expression values were calculated (regularized log counts) for each annotated gene, with an average of 92% of the reads aligning to the reference, and 75% of all reads aligning to exons. Principle component analysis of A. niger gene expression for the cultures grown in each of the different media for 24 hours indicated three clearly discernable gene expression profiles (Fig. 1). The transcriptional responses of fungi grown on GMS and DRC were relatively more distinct, while cultures grown in both LRP and DRP were more similar. Transcriptome studies are a common strategy to characterize gene expression relevant to a given process or target organism. Similar studies have characterized the transcriptional response of Aspergillus species to growth on sugarcane bagasse for biomass processing [29,30]. Further, food grade enzymes from A. oryzae have been evaluated for use in wheat gluten detoxification as well as digestion of peanut and cashew allergen digestion [11,31,32]. This strategy has also been used to characterize several topics related to aflatoxin-producing Aspergillus species. For example, transcriptional studies have been used to characterize regulators of aflatoxin production [33,34] as well as growth response to water limitation and temperature fluctuation [35,36]. Conversely, the transcriptional response to Aspergillus flavus infection in peanut plants has been used to identify genes involved in the resistance mechanism to fungal infection and the interplay between fungus and plant during infection [31,37,38]. These types of studies provide useful information on genes that can be used to enhance host plant resistance to contamination by A. flavus using conventional breeding or transgenic approaches such as overexpression of resistance-associated genes or host-induced gene silencing strategies [39–41].

| Figure 1: Distinct gene expression patterns in response to defatted nut flour media. Principle component analysis of A. niger transcriptional response to growth on LRP (purple dots), DRP (green dots), DRC (peach dots), or GMS (blue dots). [Click here to view] |

3.2. Gene Expression Trends During Growth on Nut-Flour Based Media

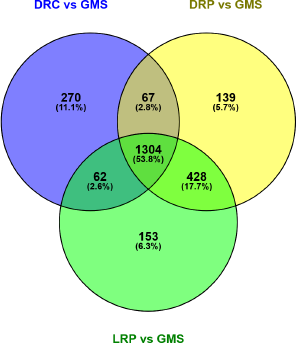

Analysis of differential gene expression indicated that there were 2,423 upregulated genes in response to A. niger cultures grown on at least one of the three nut flour containing media (LRP, DRP, and DRC) compared to the GMS media (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S1). There were 1,140 (or 47%) genes in this group encoding hypothetical proteins (based upon fungal blast results). Several of the genes encoding hypothetical proteins were among the most highly upregulated (~250-fold or more) in each of the nut flour-based media including gene_8295, gene_7693, gene_4060, gene_4515, and gene_10247.

Some general metabolic trends were observed for each of the nut flour-based media when compared to GMS. A number of fungal genes involved in protein metabolism were upregulated in the nut flour media that would be expected to aid in the breakdown and utilization of nut seed storage proteins, and the differential expression of several peptidases in the cultures grown in the nut flour-based media was observed, particularly in the DRP-based media (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table S1). Gene ontology analysis indicated greater than 60 genes encoding protein degradation related gene products among those differentially regulated in cultures grown on nut flour containing media, and at least 12 of these were involved in ubiquitin mediated proteolysis. There were several genes encoding predicted cysteine peptidases, aspartic peptidases, and serine carboxypeptidases. Some of these peptidases have been well-characterized, such as oryzin and aspergillopepsin, and are used in many industrial and food applications. For example, the oryzin protease (gene_324) was upregulated (~128-fold or more) in response to growth on each of the media containing nut flour. Likewise, the aspartic endopeptidase Aspergillopepsin (gene_1641) was upregulated (~90-fold or more) in response to growth on each of the nut flour media. Aspergillopepsin (gene_1641) has been reported to be a dominant protease in A. niger and is upregulated during growth in a wheat bran media when compared to a sugar beet pulp media [42]. In contrast, aspergillopepsin gene expression has been shown to be downregulated in response to stress such as the presence of hydrogen peroxide [43]. Proteomic analysis of A. flavus during growth on culture broths made from starch- or corn kernel-based media also indicated upregulated production of aspergillopepsin and oryzin [18]. Consistent with the observations in this report, aspergillopepsin was also identified in a previous proteomic analysis of proteins upregulated in response to fungal growth on cashew nut flour [11]. Several other enzymes involved in proteolysis were highly upregulated in cultures grown in nut flour containing media; the S28 family serine peptidase (gene_724), the A4 family peptidase (gene_920), and the S15 dipeptidyl peptidase (gene_5765) were all upregulated 20-fold or more. Other peptidases including gene_8133 and gene_11421 (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table S1) encoding putative cysteine-type endopeptidases and several serine-type peptidases, gene_724, gene_5441, and gene_3557 were also upregulated—but are not as well studied. Perhaps a more in-depth focus on the proteins that these genes encode will lead to new enzymatic options for hard to digest nut allergens such as the Ara h 2, Ara h 6, and Ara h 7 peanut allergens, the Ana o 3 cashew allergen as well as other 2S albumin proteins. The proteins encoded by the peptidase genes observed in this study may one day enable novel processes for industrial processing of nuts, nut allergens, or as protein engineering targets to develop digestive aids for degradation of digestion-resistant allergens.

| Figure 2: Overlapping and distinct gene expression patterns in response to defatted nut flour media. Venn diagram showing the overlapping upregulated genes between A. niger grown on LRP, DRP, and DRC when compared to growth on GMS. [Click here to view] |

Several genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism pathways were significantly altered in cultures grown in the nut flour containing media, which likely reflects the more complex make-up of the sugars contained within the nut flours. For example, several genes encoding proteins involved in pentose and glucuronate interconversions, including pectate lyase (gene_5667, gene_1008, gene_10052, gene_7013, and gene_7109), polygalacturonase (gene_2958, gene_9636, and gene_2622), D-xylose reductase (gene_1973), and D-xylulose reductase (gene_2974, gene_4484, gene_12076, and gene_3367), were upregulated in at least one nut-flour (LRP, DRP, and DRC) containing media compared to GMS media (Fig. 4). Many of the genes involved in galactose metabolism, including alpha-galactosidase (gene_780, gene_36, gene_6660, gene_10241, and gene_1095), two inulinase genes (gene_9975 and gene_3851), an alpha-xylosidase (gene_287), an alpha-glucosidase gene (gene_1552), and a D-galactonate dehydratase (gene_9088), were upregulated in at least one nut flour media when compared to the GMS media (Fig. 4).

| Figure 3: Peptidase gene expression, including the alkaline proteinase oryzin (gene_324), the aspartic proteinase aspergillopepsin (gene_1641), an S28 family serine peptidase (gene_724), and a hypothetical cysteine-type endopeptidase (gene_8133), is upregulated during growth on nut flour media. Heat map showing scaled rlog expression values of the peptidase genes in A. niger during growth on nut flour media in comparison to glucose as the carbon source. Gene transcripts were compared between LRP, DRP, DRC, and GMS media. Dark blue indicates −;2 and dark red indicates +2 scaled relative gene expression. Gene designations are indicated at the right of the plot. [Click here to view] |

The nut flours used for media preparation were all defatted; however, the defatting process was not complete, and some lipid content likely remained in these media. The upregulation of genes involved in fatty acid metabolism, including long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase (gene_4281), acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (gene_9730), enoyl-CoA hydratase (gene_4815 and gene_2178), and NRPS-like enzyme (gene_5750), was observed when cultures were grown in a nut flour based media compared to GMS (Fig. 4).

3.3. Peanut Specific Gene Expression Changes

Many of the genes upregulated in response to LRP and DRP were shared. There were 428 differentially regulated genes that were uniquely shared between LRP and DRP when compared to GMS media (Fig. 2). Nearly half (44%) of these, or 187 genes, encoded hypothetical proteins, and 345 (81%) were upregulated genes. Among the upregulated genes were several involved in fructose and mannose metabolism, pentose and glucuronate interconversions, and other carbohydrate metabolism including cellobiohydrolases, glucanases, xylanases, and pectate lyases. Among the carbohydrate metabolism genes that were observed to be most highly upregulated in both LRP and DRP were; extracellular cellobiohydrolase (gene_3174), endoglucanase-4 (gene_3546), endo-beta-1,4-glucanase B (gene_5519), rhamnogalacturonate lyase A (gene_725), endo-1,4-beta-xylanase A (gene_1662), endo-1,4-beta-xylanase F1 (gene_8320), and pectate lyase plyB (gene_7109). There was also a glutathione S-transferase (GST) Ure2-like protein (gene_12393) that was upregulated approximately 16-fold during growth in both LRP and DRP compared to GMS media.

| Figure 4: Volcano plots of differential gene expression responses comparing LRP, DRP, and DRC to GMS media, DRP to LRP, and DRC to DRP. Genes present in the pentose and glucuronate interconversion pathway enzymes (A), galactose metabolism pathway enzymes (B), fructose and mannose metabolism pathway enzymes (C), and fatty acid degradation (D) are highlighted in red. KEGG pathways are labeled at the right of each plot, log2 fold change indicated on the x-axis, and the absolute log10 adjusted pvalue on the y-axis. [Click here to view] |

There were 153 differentially regulated genes unique to LRP, while 139 genes were unique to DRP when compared to growth on GMS media (Fig. 2). Of these, 121 were upregulated in LRP and 87 in DRP (Supplementary Table S1). Many of these genes, 65 (42%) in LRP and 87 (63%) in DRP, encoded hypothetical proteins. Further, in both cases, several of the most highly upregulated genes (50-fold or more) unique to the LRP or DRP media encoded hypothetical proteins.

3.4. Cashew Flour Specific Gene Expression Changes

The transcriptional response to DRC media was markedly distinct from the peanut flour-based media. There were 270 differentially expressed genes unique to growth in the DRC media (Fig. 2). Of these, 133 (or 49%) encoded hypothetical proteins and several of these were among the most highly upregulated including gene_10310, gene_10311 (over 350-fold) and gene_3193 and gene_12324 (over 35 fold). Other genes that were observed to be upregulated during growth in DRC media included cytochrome p450s (gene_3049, gene_7091), and several integral membrane proteins, some of which are involved in transporter activities (gene_3020, gene_2392, gene_3041, gene_2876, and gene_175).

3.5. Dark Roasted Nut Flour Specific Gene Expression Changes

Heating foods can drive the formation of chemicals including Maillard reaction products, acrylamide, or other potentially harmful compounds. There were 67 genes differentially expressed in both the DRP and DRC media. Twenty-five were upregulated suggesting that they may encode proteins involved in break-down and/or detoxification of heating induced compound formation. Of these, 11 (44%) encoded hypothetical proteins. For example, gene_7759 and gene_6743 were upregulated (over 12-fold) in both media and may encode enzymes capable of modifying—or aid in metabolizing—the types of heating-induced byproducts mentioned above. Several genes involved in drug/xenobiotic metabolism (p450 enzymes), as well as genes involved in organic/aromatic compound, cyanoamino acid, chlorocyclohexane, chlorobenzene, and aminobenzoate metabolism, were upregulated in both the DRP and DRC media. For example, gene_8260 encodes a hypothetical protein with predicted monooxygenase activity and those encoding cytochrome p450 enzymes (gene_169 and gene_1638) were upregulated at least 8-fold. In addition, several genes encoding lipid metabolism enzymes and detoxifying or xenobiotic metabolism genes (p450s) were upregulated during growth on nut flour media.

While not specific to the dark roasted nut flour media (DRP and DRC), a number of monooxygenase, cytochrome p450, and disulfide oxidoreductase genes that may be involved in detoxification steps were upregulated during growth on all three of the nut flour based media. Gene ontology term enrichment analysis identified 112 upregulated genes encoding monooxygenases, 72 p450 enzymes and also identified 8 upregulated genes encoding proteins with predicted glutathione transferase activity. For example, a putative glutathione S-transferase (GST) II-like protein (gene_12053) was upregulated approximately 250-fold, while a glutathione S-transferase (gene_7959) and another gene (gene_10900) encoding a glutathione S-transferase Ure2-like protein were upregulated at least 8-fold. Gene_3130, encoding a hypothetical protein with predicted carbon-sulfur lyase activity, was upregulated over 50-fold. Another gene encoding a protein with predicted carbon-sulfur lyase activity (gene_5689) was upregulated at least 20-fold.

Heating can alter protein solubility, and it can induce structural and chemical changes in food proteins that can create advanced glycation endproducts, heterocyclic amines, acrylamide, and polycylic aromatic hydrocarbons [44–46]. Heating-induced generation of xenobiotic compounds may lead to upregulation of genes encoding detoxification enzymes that could be used for their metabolism. Several genes involved in various aspects of xenobiotic compound metabolism were observed to be upregulated. Further, despite intensive processing during preparation for consumers, cashew nuts have been demonstrated to contain residual anacardic acid content [47]. Anacardic acids are phenolic compounds present in cashews that can cause severe skin irritation, but that have also been associated with anti-microbial, histone acetyltransferase inhibition, anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory pharmacological activities [48,49]. Plant compounds remaining in the peanut and cashew nut-flour based media could also be responsible for upregulation of detoxifying enzymes. There were several glutathione S-transferase type genes that may function to detoxify exogenous compounds that were upregulated in response to growth on nut flour media. These observations are consistent with previously published work demonstrating the upregulation of a GST protein in the guts of Helicoverpa zea larvae that had been fed a cashew nut flour diet [50]. There were 25 upregulated genes that were uniquely shared between DRP and DRC, suggesting some of these may be in response to the dark-roasted nature of the nut flours for these media and may encode proteins useful for metabolizing heating-induced byproducts that may be toxic or other modifications to food components that render them potentially harmful. The observations presented in this work could enable the development of detoxifying enzymes that may find medically related or industrial food processing applications.

4. CONCLUSION

Many nut flour specific gene expression changes were observed in the analysis presented here; indicating clear metabolic shifts to adjust for components of each nut flour-based media. Characterization of peptidases such as gene_8419, gene_6678, gene_724, and gene_920 may enable improved allergen metabolism. In addition, several genes encoding lipid metabolism enzymes and detoxifying or xenobiotic metabolism genes (p450s) were upregulated during growth on nut flour media. There were a large number of genes encoding hypothetical proteins of unknown function that were also observed to be upregulated. It could be useful to determine the functional roles of the proteins encoded by many of these highly differentially expressed hypothetical genes. Continued exploration of the genes highlighted in this work will serve as a resource for enzymes involved in the degradation of plant seed storage proteins and carbohydrate metabolism for genetic engineering of enzymes with improved activity and engineered strain improvements.

5. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Greg Thyssen, Matt Lebar, Yvette Bren-Mattison, and Michael Santiago for helpful discussion and critical evaluation of the material presented in this report.

6. AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

CPM, BM, and JWC conceived the project. CPM and JWC performed the experimental and laboratory work. BM and CPM analyzed and interpreted the data regarding fermentation. CPM authored the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors consent to publication.

7. ETHICAL APPROVAL

This study does not involve the use of animals or human subjects.

8. CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

9. FUNDING

This research was supported by funds from the U.S. Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or companies in this article is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

REFERENCES

1. Gupta RS, Warren CM, Smith BM, Jiang J, Blumenstock JA, Davis MM, et al. Prevalence and severity of food allergies among US adults. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2(1):e185630. CrossRef

2. Gupta RS, Warren CM, Smith BM, Blumenstock JA, Jiang J, Davis MM, et al. The public health impact of parent-reported childhood food allergies in the United States. Pediatrics 2018;142(6):e20181235. CrossRef

3. Ochfeld EN, Pongracic JA, Food allergy: diagnosis and treatment. Allergy Asthma Proc 2019;40(6):446–9. CrossRef

4. Ponce M, Diesner SC, Szepfalusi Z, Eiwegger T. Markers of tolerance development to food allergens. Allergy 2016;71(10):1393–404. CrossRef

5. Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, Bahnson HT, Radulovic S, Santos AF, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med 2015;372(9):803–13. CrossRef

6. Du Toit G, Sayre PH, Roberts G, Sever ML, Lawson K, Bahnson HT, et al. Effect of avoidance on peanut allergy after early peanut consumption. N Engl J Med 2016;374(15):1435–43. CrossRef

7. Costa J, Bavaro SL, Benede S, Diaz-Perales A, Bueno-Diaz C, Gelencser E, et al. Are physicochemical properties shaping the allergenic potency of plant allergens? Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2020. doi: 10.1007/s12016-020-08810-9 CrossRef

8. Souza PFN. The forgotten 2S albumin proteins: Importance, structure, and biotechnological application in agriculture and human health. Int J Biol Macromol 2020; 164:4638–49. CrossRef

9. Mattison CP, Grimm CC, Wasserman RL. In vitro digestion of soluble cashew proteins and characterization of surviving IgE-reactive peptides. Mol Nutr Food Res 2014;58(4):884–93. CrossRef

10. Palladino C, Breiteneder H, Peanut allergens. Mol Immunol 2018;100:58–70. CrossRef

11. DeFreece CB, Cary JW, Grimm CC, Wasserman RL, Mattison CP. Treatment of cashew extracts with aspergillopepsin reduces IgE binding to cashew allergens. J Appl Biol Biotechnol 2016;4(2):001–10.

12. Mattison CP, Grimm CC, Li Y, Chial HJ, McCaslin DR, Chung SY. et al. Identification and characterization of Ana o 3 modifications on arginine-111 residue in heated cashew nuts. J Agric Food Chem 2017; 65(2):411–20. CrossRef

13. Mikiashvili N, Yu J. Changes in immunoreactivity of allergen-reduced peanuts due to post-enzyme treatment roasting. Food Chem 2018;256:188–94. CrossRef

14. Kulis M, Macqueen I, Li Y, Guo R, Zhong XP, Burks AW. Pepsinized cashew proteins are hypoallergenic and immunogenic and provide effective immunotherapy in mice with cashew allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;130(3):716–23. CrossRef

15. Adrio JL, Demain AL. Microbial enzymes: tools for biotechnological processes. Biomolecules 2014; 4(1):117–39. CrossRef

16. Chandra P, Enespa, Singh R, Arora PK. Microbial lipases and their industrial applications: a comprehensive review. Microb Cell Fact 2020;19(1):169. CrossRef

17. Singh R, Kumar M, Mittal A, Mehta PK. Microbial enzymes: industrial progress in 21st century. 3 Biotech 2016;6(2):174. CrossRef

18. Duran RM, Gregersen S, Smith TD, Bhetariya PJ, Cary JW, Harris-Coward PY, et al. The role of Aspergillus flavus veA in the production of extracellular proteins during growth on starch substrates. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2014;98(11):5081–94. CrossRef

19. Jin FJ, Hu S, Wang BT, Jin L. Advances in genetic engineering technology and its application in the industrial fungus Aspergillus oryzae. Front Microbiol 2021; 12:644404. CrossRef

20. Ganiats TG, Norcross WA, Halverson AL, Buford PA, Palinkas LA. Does Beano prevent gas?: a double-blind crossover study of oral alpha-galactosidase to treat dietary oligosaccharide intolerance. J Fam Pract 1994;39(5):441–5.

21. Merz M, Eisele T, Berends P, Appel D, Rabe S, Blank I, et al. Flavourzyme, an enzyme preparation with industrial relevance: automated nine-step purification and partial characterization of eight enzymes. J Agric Food Chem 2015;63(23):5682–93. CrossRef

22. Bitencourt TA, Macedo C, Franco ME, Assis AF, Komoto TT, Stehling EG. et al. Transcription profile of Trichophyton rubrum conidia grown on keratin reveals the induction of an adhesin-like protein gene with a tandem repeat pattern. BMC Genomics 2016;17:249. CrossRef

23. Mattison CP, Desormeaux WA, Wasserman RL, Yoshioka-Tarver M, Condon B, Grimm CC. Decreased immunoglobulin E (IgE) binding to cashew allergens following sodium sulfite treatment and heating. J Agric Food Chem 2014;62(28):6746–55. CrossRef

24. Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ. et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol 2010;28(5):511–5. CrossRef

25. Wu TD, Reeder J, Lawrence M, Becker G, Brauer MJ. GMAP and GSNAP for genomic sequence alignment: enhancements to speed, accuracy, and functionality. Methods Mol Biol 2016;1418:283–334. CrossRef

26. Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014;30(7):923–30. CrossRef

27. Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014;15(12):550. CrossRef

28. Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Morishima K. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG tools for functional characterization of genome and metagenome sequences. J Mol Biol 2016;428(4):726–31. CrossRef

29. Midorikawa GEO, Correa CL, Noronha EF, Filho EXF, Togawa RC, Costa M, et al. Analysis of the transcriptome in Aspergillus tamarii during enzymatic degradation of sugarcane bagasse. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2018;6:123. CrossRef

30. de Gouvea PF, Bernardi AV, Gerolamo LE, de Souza Santos E, Riano-Pachon DM, Uyemura SA, et al. Transcriptome and secretome analysis of Aspergillus fumigatus in the presence of sugarcane bagasse. BMC genomics 2018;19(1):232. CrossRef

31. Korani W, Chu Y, Holbrook CC, Ozias-Akins P. Insight into genes regulating postharvest aflatoxin contamination of tetraploid peanut from transcriptional profiling. Genetics 2018;209(1):143–56. CrossRef

32. Shi X, Guo R, White BL, Yancey A, Sanders TH, Davis JP, et al. Allergenic properties of enzymatically hydrolyzed peanut flour extracts. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2013;162(2):123–30. CrossRef

33. Gilbert MK, Mack BM, Wei Q, Bland JM, Bhatnagar D, et al. RNA sequencing of an nsdC mutant reveals global regulation of secondary metabolic gene clusters in Aspergillus flavus. Microbiol Res 2016;182:150–61. CrossRef

34. Cary JW, Entwistle S, Satterlee T, Mack BM, Gilbert MK, Chang PK. et al. The transcriptional regulator Hbx1 affects the expression of thousands of genes in the aflatoxin-producing fungus Aspergillus flavus. G3 (Bethesda) 2019;9(1):167–78. CrossRef

35. Medina A, Gilbert MK, Mack BM, OBrian GR, Rodriguez A, Bhatnagar D, et al. Interactions between water activity and temperature on the Aspergillus flavus transcriptome and aflatoxin B1 production. Int J Food Microbiol 2017;256:36–44. CrossRef

36. Gilbert MK, Medina A, Mack BM, Lebar MD, Rodriguez A, Bhatnagar D, et al. Carbon dioxide mediates the response to temperature and water activity levels in Aspergillus flavus during infection of maize kernels. Toxins 2017;10:(1):5. CrossRef

37. Nayak SN, Agarwal G, Pandey MK, Sudini HK, Jayale AS, Purohit S, et al. Aspergillus flavus infection triggered immune responses and host-pathogen cross-talks in groundnut during in-vitro seed colonization. Sci Rep 2017;7(1):9659. CrossRef

38. Wang H, Lei Y, Yan L, Wan L, Ren X, Chen S, et al. Functional genomic analysis of Aspergillus flavus interacting with resistant and susceptible peanut. Toxins 2016;8(2):46. CrossRef

39. Gilbert MK, Majumdar R, Rajasekaran K, Chen ZY, Wei Q, Sickler CM, et al. RNA interference-based silencing of the alpha-amylase (amy1) gene in Aspergillus flavus decreases fungal growth and aflatoxin production in maize kernels. Planta 2018;247(6):1465–73. CrossRef

40. Power IL, Dang PM, Sobolev VS, Orner VA, Powell JL, Lamb MC, et al. Characterization of small RNA populations in non-transgenic and aflatoxin-reducing-transformed peanut. Plant Sci 2017;257:106–25. CrossRef

41. Majumdar R, Rajasekaran K, Sickler C, Lebar M, Musungu BM, Fakhoury AM, et al. The pathogenesis-related maize seed (PRms) gene plays a role in resistance to Aspergillus flavus infection and aflatoxin contamination. Front Plant Sci 2017;8:1758. CrossRef

42. Budak SO, Zhou M, Brouwer C, Wiebenga A, Benoit I, Di Falco M, et al. A genomic survey of proteases in Aspergilli. BMC genomics 2014;15:523. CrossRef

43. Fountain JC, Bajaj P, Nayak SN, Yang L, Pandey MK, Kumar V, et al. Responses of Aspergillus flavus to oxidative stress are related to fungal development regulator, antioxidant enzyme, and secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene expression. Front Microbiol 2016;7:2048. CrossRef

44. ALjahdali N, Carbonero F. Impact of Maillard reaction products on nutrition and health: current knowledge and need to understand their fate in the human digestive system. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2019;59(3):474–87. CrossRef

45. Alaejos MS, Afonso AM. Factors that affect the content of heterocyclic aromatic amines in foods. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2011;10(2):52–108. CrossRef

46. De Paola EL, Montevecchi G, Masino F, Garbini D, Barbanera M, Antonelli A. Determination of acrylamide in dried fruits and edible seeds using QuEChERS extraction and LC separation with MS detection. Food Chem 2017;217:191–5. CrossRef

47. Mattison CP, Malveira Cavalcante J, Izabel Gallao M, Sousa de Brito E. Effects of industrial cashew nut processing on anacardic acid content and allergen recognition by IgE. Food Chem 2018;240:370–6. CrossRef

48. Suo M, Isao H, Ishida Y, Shimano Y, Bi C, Kato H, et al. Phenolic lipid ingredients from cashew nuts. J Nat Med 2012;66:133–9. CrossRef

49. Hemshekhar M, Sebastin Santhosh M, Kemparaju K, Girish KS. Emerging roles of anacardic acid and its derivatives: a pharmacological overview. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2012;110(2):122–32. CrossRef

50. Mattison CP, Dowd PF, Tarver MR, Grimm CC. Induction of glutathione S-transferase in Helicoverpa zea fed cashew flour. Entomol Appl Sci Lett 2014;1(4):60–9.