INTRODUCTION

Protease enzymes are essential for hydrolyzing peptide bonds within polypeptide chains composed of amino acids. They are ubiquitous across organisms, including plants, animals, and microorganisms, and are known for their specificity and selectivity in modifying proteins. Recent decades have seen revolutionary advancements in biocatalysis, integrating multidisciplinary technologies, and leveraging natural enzymatic reactions. Approximately one-third of the total enzyme production in industries worldwide is currently occupied by proteases. Approximately 60% of proteases used in industries are economically produced by microorganisms, including bacteria, molds, and yeasts that are responsible for generating around 40% of the chemicals used in various industries today [1-4] Proteases are engineered to function under physiological conditions and are frequently utilized to catalyze a wide range of organic transformations. However, in the context of biocatalysis, the focus is on employing proteases as effective process catalysts under specific and tailored environmental conditions.

In industry, the proteases isolated from thermophiles are much preferred as they tend to be stable at higher temperatures in industrial manufacturing processes. This leads to considerably accelerated reaction rates, increased solubility of non-gaseous reactants and products, and diminished susceptibility to microbial contamination by mesophiles [5]. Proteases used in industrial applications, such as in detergents and leather processing, must demonstrate stability at high temperatures. The broad-spectrum application of such enzymes in chemicals, food, pharmaceuticals, paper, textiles, and others primarily owes their resilience to denaturation and exceptional operational stability at elevated temperatures [6,7].

The industrial demand for enzymes that exhibit stability and activity in non-aqueous media is increasing more than ever, primarily due to their expanding utility in organic synthesis [8]. In the field of peptide synthesis, the application of proteases is currently limited due to their specificity and susceptibility in the presence of organic solvents, as numerous reactions occur in organic media [9]. The identification of microorganisms with thermostable and non-aqueous stable proteases also requires a focus on the optimization of microbial protease production [10]. Several factors include nutritional requirements and physical parameters, including pH, temperature, aeration, and agitation. These factors, when optimized for the culturing and cultivation processes, can lead to optimal protease production [11].

The present study aimed to identify suitable bacterial strains from soil samples that can deliver protease that is thermostable and possesses optimal activity in the presence of organic solvents and salt stress.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Isolation and Characterization of Protease-Producing Bacteria

The soil sampled from Malappuram District, Kerala, India, demonstrated loamy to clayey textures with notable gravel content [Figure 1A]. Employing sterile techniques, the soil underwent enrichment, serial dilutions, and subculturing on nutrient agar, resulting in the growth of eight distinct colonies with diverse morphological characteristics [Figures 1A,B].

| Figure 1: Isolation of potent protease producing bacteria from soil sample. (A) Soil sample, (B) 1X solution of the soil sample, (C) Colonies from different serial dilutions from soil sample solution, (D) Isolated pure colonies from serial dilution, (E) Gelatin hydrolysis of isolated samples, (F) Casein hydrolysis of isolated samples, (G) Mass production of potent protease producers.

[Click here to view] |

Enzymatic index (EI) analysis for gelatin and casein hydrolysis revealed significantly higher protein hydrolysis efficiency in isolates one, four, and seven compared to others [Figures 1C-F; Tables 1 and Figures 1E,G, Table 3].

Table 1: Hydrolysis results – Gelatin & Casein.

| Isolates | Gelatin hydrolysis | Casein hydrolysis |

|---|

| Diameter of zone of degradation (mm) | Enzymatic index (Diameter of zone of degradation (mm) / Colony diameter) | Diameter of zone of degradation (mm) | Enzymatic index (Diameter of zone of degradation (mm)/Colony diameter) |

|---|

| Isolate 1 | 16 mm | 2.28 | 17 mm | 2.125 |

| Isolate 2 | - | - | - | - |

| Isolate 3 | 14 mm | 1.75 | 19 mm | 1.58 |

| Isolate 4 | 19 mm | 2.11 | 18 mm | 1.38 |

| Isolate 5 | 15 mm | 1.25 | 17 mm | 1.54 |

| Isolate 6 | - | - | - | - |

| Isolate 7 | 17 mm | 1.88 | 16 mm | 1.6 |

| Isolate 8 | - | - | - | - |

Table 2: Proteolytic activity of the isolates.

| Isolates | Concentration of tyrosine released(mg/ml) | Enzyme activity (U/mL) |

| Isolate 1 | 20.030 ± 0.08 | 36.850 ± 0.08 |

| Isolate 4 | 15.056 ± 0.06 | 27.698 ± 0.08 |

| Isolate 7 | 13.025 ± 0.11 | 23.963 ± 0.09 |

Table 3: Biochemical characterization of the Isolate 1.

| Tests | Isolate 1 |

|---|

| Indole test | –ve |

| Methyl red test | –ve |

| Voges proskauer test | –ve |

| Citrate utilization test | +ve |

| Urease production test | –ve |

| Triple sugar iron agar test | K/K no H2S production |

| Sugar fermentation |

| Glucose | +ve |

| Lactose | –ve |

| Sucrose | +ve |

| Maltose | +ve |

| Oxidase test | –ve |

| Catalase test | +ve |

Morphological and microscopic examination of isolate one exhibited large, feathery, gray, granular, spreading, and opaque colonies with irregular margins [Figures 4B,C].

| Figure 2: Enzyme production study. (A) Standard curve for tyrosine used for calculating enzyme activity; Optimization of enzyme production, (B) incubation time, (C) temperature, and (D) pH.

[Click here to view] |

| Figure 3: Effect on protease production by, (A) Sodium chloride, (B) Standard curve for tyrosine estimation, (C) carbon sources, (D) nitrogen sources.

[Click here to view] |

| Figure 4: Biochemical characterization of bacterial isolates, (A) pure culture of isolate one, (B) Gram staining, (C) IMViC test, (D) Catalase test, (E) Oxidase test.

[Click here to view] |

Soil harbors a rich diversity of microorganisms, influenced by its composition and environmental conditions. Previous research worldwide has isolated various soil microorganisms with potential applications in antibacterial compounds, pigments, and industrial enzymes [16,17]. In our study, we isolated eight distinct bacterial strains from soil samples, each exhibiting unique morphological and biochemical characteristics. In contrast, a study conducted in Antarctica [18,19] successfully isolated seventy-five strains for alkaline protease production, highlighting the versatility of soil microorganisms across different environments. Identifying bacterial strains based on morphology alone can be challenging, as variations may arise from differential gene expression. Gene expression influences the synthesis of specific proteins, impacting cell structure and function, and leading to observable morphological differences.

Biochemical tests, including indole, methyl red, Voges Proskauer, Simmons citrate, catalase, oxidase, urease, and carbohydrate fermentation tests (glucose, sucrose, maltose, and lactose), aided in the preliminary identification of the isolated bacterial strain as belonging to the Bacillus species. Utilizing multivariate techniques [Figures 4D, E] offers a comprehensive approach to bacterial identification, with each method having its own strengths and weaknesses [20,26]. These tests evaluate metabolic activities such as substrate utilization and enzyme production, providing insights into the physiological characteristics of the bacterial isolates.

3.2. 16S rRNA Analysis

Isolate one, identified as Bacillus cereus, and was subjected to gene-based screening using 16S ribosomal RNA sequences with universal primers. Sanger sequencing of the 16S rRNA sequences revealed the highest identity (99.92%) with the P1 strain of B. cereus, ranging from 650 to 800 bases. The phylogenetic analysis included this strain along with nine other similar sequences [24]. The resulting phylogenetic tree [Figure 6C] displayed the P1 strain as the outgroup, indicating a more distantly related group. Two main clades branched from a common ancestor: rRNA strains A-D and E-H. Within these clades, A and B, as well as G and H, were closely related. Notably, strains I and H exhibited a distance of 0.016 (0.05 + 0.011) generic changes. Isolate one, identified as B. cereus, demonstrated superior enzyme activity in gelatin and casein degradation compared to other isolates.

| Figure 5: Protease purification and enzyme activity, (A) Bacterial biomass production media, ammonium sulfate precipitation of protease crude extract, and membrane dialysis purification, (B) Enzyme activity of various fractions of from sephadex G-100, (C) Enzyme activity of various fractions from DEAE-Sephadex A50 anion exchange column.

[Click here to view] |

| Figure 6: Protease purification validation by, (A) SDS-PAGE, and (B) Zymogram Assay, (C) Phylogenetic tree of the protease-producing bacteria based on 16S rRNA gene sequence blast and sequence alignment results.

[Click here to view] |

3.3. Optimization of Growth Conditions

Protease production from B. cereus was optimized across multiple growth parameters, as illustrated in Figure 3].

The isolates displayed varying strengths in protease production, with distinct enzymatic activities observed in each. Bacillus species’ bacterial isolates have shown effectiveness in extracellular protease production, consistent with previous studies by Alnahdi and Verma [21,22]. Notably, the isolate demonstrated a higher ratio of biomass production and alkaline protease activity, suggesting its potential for larger-scale commercial applications.

3.4. Enzyme Characterization

B. cereus was cultured in production media under optimized conditions, as described in section 3.4 [Figure 5A]. Following incubation, a crude enzyme unit was obtained, and subsequent downstream purification techniques were applied to isolate the protease enzyme. Evaluation of the crude enzyme’s protease activity using the Folin-Ciocalteau reagent at 660 nm revealed an activity of 72.212 ± 0.235 U/ml.

The purity of the isolated fractions was assessed through SDS-PAGE, which showed a single band corresponding to a 40 kDa protein weight, consistent with the standard protein marker. Zymogram staining confirmed proteolytic activity against a blue background, aligning with positions on the gel corresponding to the 40 kDa marker observed in SDS-PAGE [Figures 6A,B].

Peak protease activity of the eluted fractions from Sephadex-G 100 chromatography was observed in the range of 58 to 71 [Figure 5B]. These specific fractions (58 to 71) were collected and further eluted in a DEAE-Sephadex A-50 column. The protease activity of the eluted product was most prominent in fractions 37 to 54, with the 47th peak exhibiting the highest efficacy [Figure 5C].

Protein concentration was monitored at each purification step using Lowry’s method, demonstrating an increase in purification fold alongside enhanced enzyme activity (U/mL) [Table 5]. The DEAE-Sephadex A-50 column exhibited the highest enzyme activity, which was notably comparable to that of Sephadex-G 100.

Table 4: Identification of the potent isolate.

| Isolate | Sequence | Identity | Accession ID |

|---|

| 1 | GATTGGATTA AGAGCTTGCT CTTATGAAGT

TAGCGGCGGA CGGGTGAGTA ACACGTGGGT

AACCTGCCCA TAGGACTGGG ATAACTCCGG

GAAACCGGGG CTAATACCGG ATAACATTTT

GAACCGCATG GTTCGAAATT GAATGGCGGC

TTCGGCTGTC ACTTATGGAT GGACCCGCGT

CGCATTAGCT AGTTGGTGAG GTAA CGGCTC

ACGAAGGCAA CGATGCGTAG CCGACCTGAG

AGGGTGATCG GCCACACTGG GACTGAGACA

CGGCCCAGAC TCCTACGGGA GGCAGCAGTA

GGGAATCTTC CGCAATGGAC GAAAGTCTGA

CGGAGCAACG CCGCGTGAGT GATGAAGGCT

TTCGGGTCGT AAAACTCTGT TGTTAGGGAA

GAACAAGTGC TAGTTGAATA AGCTGGCACC

TTGACGGTAC CTAACCAGAA AGCCACGGCT

AACTACGTGC CAGCAGCCGC GGTAATACGT

AGGTGGCAAG CGTTATCCGG AATTATTGGG

CGTAAAGCGC GCGCAGGTGG TTTCTTAAGT

CTGATGTGAA AGCCCACGGC TGAACCGTGG

AGGGTCATTG GAAACTGGGA GACTTGAGTG

CAGAAGAGGA AAGTGGAATT CCATGTGTAG

CGGTGAAATG CGTAGAGATA TGGAGGAACA

CCAGTGGCGA AGGCGACTTT CTGGTCTGTA

ACTTACACTG AGGCGCGAAA GCGTGGGGAG

CAAACAGGAT TAGATACCCT GGTAGTCCAC

GCCGTAAACG ATGAGTGCTA AGTGTTAGAG

GGTTTCCGCC CTTTAGTGCT GAAGTTAACG

CATTAAGCAC TCCGCCTGGG GAGTACGGCC

GCAAGGCTGA AACTCAAAGG AATTGACGGG

GGCCCGCACA AGCGGTGGAG CATGTGGTTT

AATTCGAAGC AACGCGAAGA ACCTTACCAG

GTCTTGACAT CCTCTGAAAA CCCTAGAGAT

AGGGCTTCTC CTTCGGGAGC AGAGTGACAG

GTGGTGCATG GTTGTCGTCA GCTCGTGTCG

TGAGATGTTG GGTTAAGTCC CGCAACGAGC

GCAACCCTTG ATCTTAGTTG CCATCATTAA

GTTGGGCACT CTAAGGTGAC TGCCGGTGAC

AAACCGGAGG AAGGTGGGGA TGACGTCAAA

TCATCATGCC CCTTATGACC TGCGCTACAC

ACGTGCTACA ATGGACGGTA CAAAGAGCTG

CAAGACCGCG AGGTGGAGCT AATCTCATAA

AACCGTTCTC AGTTCGCATT GTAGGCTGCA

ACTCGCCTAC ATGAAGCTGG AATCGCTAGT

AATCGCGGA CAGCATGCCG

CGGTGAATAC | Bacillus cereus p1 | OP727433 |

Table 5: Purification table for enzyme extracted from isolate 1.

| Purification step | Volume (ml) | Protein concentration (mg/ml) | Total protein (mg) | Enzyme activity (U/ml) | Total activity (U) | Specific activity (U/mg) | Yield (%) | Purification fold |

|---|

| Culture filtrate | 200 | 2.002 ± 0.020 | 400.342 | 60.009 ± 0.012 | 12001.8 | 29.979 | 100.00 | 1.000 |

| Dialysis | 100 | 1.146 ± 0.013 | 114.628 | 72.212 ± 0.009 | 7221.2 | 62.997 | 60.168 | 2.101 |

| Sephadex-100 | 20 | 0.898 ± 0.032 | 17.964 | 173.939 ± 0.022 | 3478.787 | 193.652 | 28.986 | 6.460 |

| DEAE-Sephadex A-50 | 10 | 0.838 ± 0.023 | 8.383 | 271.620 ± 0.017 | 2716.203 | 324.004 | 22.632 | 10.808 |

The crude enzyme was effectively inhibited by phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, 5 mM), indicating the presence of serine proteases in the strain’s enzyme. Conversely, EDTA, a metalloprotease inhibitor, did not inhibit enzyme activity, confirming the absence of metalloproteases. The enzyme retained activity levels of 265.09 U/mL when preincubated with 5 mM EDTA. Similar activity levels were observed with β-mercaptoethanol (278.26 U/mL) and aprotinin (238.753 U/mL), further supporting its classification as a serine protease [Table 6].

Table 6: Characterization of protease enzyme class.

| Class of protease | Inhibitor used | Enzyme activity (U/mL) |

|---|

| Serine protease | PMSF | 0.2633 ± 0.048 |

| Cysteine protease | β-mercaptoethanol | 278.26 ± 0.022 |

| Metalloprotease | EDTA | 265.09 ± 0.060 |

| Aspartate protease | Aprotinin | 238.75 ± 0.010 |

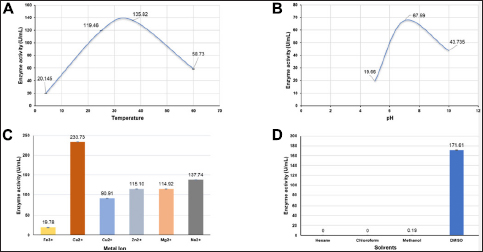

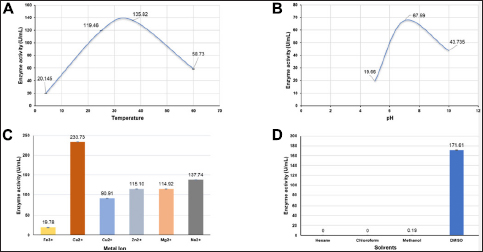

The isolated enzymes were tested for stability and activity under varying conditions of temperature, pH, metal ions, and organic solvents [Figure 8]. The maximum enzyme activity was observed at 37°C (135.825 ± 0.240 U/mL), decreasing significantly at 60°C (58.73 ± 0.522 U/mL). The optimal pH for enzyme activity was 7.0 (67.59 ± 0.0167 U/mL). Serine protease inhibitors (serpins) inhibit proteases through a conformational change.

| Figure 7: Stain Removal Test: Egg yolk stain (A-I), soy sauce stain (J-R) on white cotton, polyester and silk respectively. 500 µL and 300 µL detergent alone wash on egg yolk stain (B, E, and H) and soy sauce (K, N, and Q). Detergent and protease enzyme combination wash (500:500 µL and 300:300 µL) on egg yolk (C, F, and I) and soy sauce (L, O, and R). Microscopic surface image of all the test samples are labeled in their respective lowercases.

[Click here to view] |

| Figure 8: Effect of enzyme activity (U/mL) under varying conditions. (A) Temperature, (B) pH, (C) Presence of metal ions, (D) solvents.

[Click here to view] |

Protease activity was notably influenced by the presence of divalent metal ions [Figure 8C]. Calcium ions (Ca2+) significantly enhanced protease activity, as indicated by the highest concentration of released tyrosine and enzyme activity. Magnesium (Mg2+) and sodium (Na2+) also increased protease activity, albeit to a lesser extent. Conversely, zinc (Zn2+), copper (Cu2+), and iron (Fe2+) resulted in lower enzyme activity compared to calcium, magnesium, and sodium. These results suggest that specific divalent metal ions, particularly calcium, positively influence protease activity under the tested conditions.

In both hexane and chloroform, the tyrosine release and enzyme activity were zero, indicating that these nonpolar solvents do not support protease activity [Figure 8D]. This lack of activity suggests that proteases are not stable or active in nonpolar environments. Conversely, methanol, a polar solvent, showed minimal protease activity. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), a polar aprotic solvent, exhibited higher tyrosine release and enzyme activity, suggesting that DMSO supports protease activity better than the other solvents tested.

The purified enzymes combined with detergent effectively removed egg yolk and soy sauce stains, as demonstrated by stain washing and microscopic imaging [Figure 7]. The enzyme-detergent combination showed superior stain removal efficacy compared to detergent alone. Reflectivity studies indicated that the enzyme-detergent combination significantly reduced residual stains on and between the fibers, resulting in smoother and looser fiber arrangements. In contrast, detergent alone left some stain residues.

The effectiveness of enzyme-detergent mixtures in stain removal aligns with previous studies showing that alkaline proteases from Bacillus species excel in stain removal and have potential in the enzyme-detergent market as effective cleaning agents. The demand for organic solvent-tolerant proteases in the industrial sector is high due to their application in organic solvent-based reactions. The thermostability of these proteases further enhances their suitability for industrial applications, particularly in laundry detergent formulations.

Overall, the present study establishes the higher attributes of the isolated B. cereus serine protease in comparison to prevalent microbial proteases, specifically emphasizing its thermostability, pH stability, catalytic efficiency, inhibitor and solvent resistance, and production yield. Particularly noteworthy is the exceptional thermostability of our protease, which sustains high activity levels (72.212±0.235 U/mL) even under elevated temperatures, presenting a significant advantage for industrial processes operating at high temperatures [11]. This characteristic contrasts with the common observation of reduced stability in many Bacillus proteases under similar conditions [6-8]. Furthermore, our protease exhibits sustained high activity across a wide pH range, outperforming the narrower pH tolerances of other Bacillus proteases, thus rendering it applicable across diverse industrial sectors such as wastewater treatment and food processing [6]. Additionally, our enzyme displays elevated specific activity and efficient hydrolysis (62.997 U/mg), resulting in diminished enzyme requirements in comparison to other Bacillus proteases [19, 23, 27, 28]. Its resilience against inhibitors and compatibility with polar solvents like DMSO further augment its utility in industrial contexts where enzyme inhibition poses a prevalent challenge. Moreover, the substantial production yield of our protease facilitates scalable production, rendering it economically viable and significantly amplifying detergent efficacy on various fabric substrates, thereby conclusively establishing its superiority over extant microbial proteases.

REFERENCES

1. Sloma A, Rudolph CF, Rufo GA, Sullivan BJ, Theriault KA, Ally D, et al. Gene encoding a novel extracellular metalloprotease in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1024-9. [CrossRef]

2. Rao MB, Tanksale AM, Ghatge MS, Deshpande VV. Molecular and biotechnological aspects of microbial proteases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:597-635. [CrossRef]

3. Adinarayana K, Ellaiah P, Prasad DS. Purification and partial characterization of thermostable serine alkaline protease from a newly isolated Bacillus subtilis PE-11. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2003;4:E56. [CrossRef]

4. Subba Rao C, Sathish T, Ravichandra P, Prakasham RS. Characterization of thermo- and detergent stable serine protease from isolated Bacillus circulans and evaluation of eco-friendly applications. Process Biochem. 2009;44:262-8. [CrossRef]

5. Do Nascimento WCA, Leal Martins ML. Production and properties of an extracellular protease from thermophilic Bacillus sp. Brazilian J Microbiol. 2004;35:91-6. [CrossRef]

6. Raveendran S, Parameswaran B, Ummalyma SB, Abraham A, Mathew AK, Madhavan A, et al. Applications of microbial enzymes in food industry. Food Technol Biotechnol. 2018;56:16-30. [CrossRef]

7. Naveed M, Nadeem F, Mehmood T, Bilal M, Anwar Z, Amjad F. Protease—a versatile and ecofriendly biocatalyst with multi-industrial applications: an updated review. Catal Lett. 2021;151:307-23. [CrossRef]

8. Gupta A, Khare SK. Enhanced production and characterization of a solvent stable protease from solvent tolerant pseudomonas aeruginosa PseA. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2007;42:11-6. [CrossRef]

9. Kumar D, Bhalla TC. Microbial proteases in peptide synthesis: approaches and applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;68:726-36. [CrossRef]

10. Sellami-Kamoun A, Haddar A, Ali NEH, Ghorbel-Frikha B, Kanoun S, Nasri M. Stability of thermostable alkaline protease from Bacillus licheniformis RP1 in commercial solid laundry detergent formulations. Microbiol Res. 2008;163:299-306. [CrossRef]

11. Abusham RA, Rahman RNZRA, Salleh A, Basri M. Optimization of physical factors affecting the production of thermo-stable organic solvent-tolerant protease from a newly isolated halo tolerant Bacillus subtilis strain Rand. Microb Cell Fact. 2009;8:1-9. [CrossRef]

12. Weisburg WG, Barns SM, Pelletier DA, Lane DJ. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:697-703. [CrossRef]

13. Schumann P. E. Stackebrandt and M. Goodfellow (Editors), Nucleic Acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematics (Modern Microbiological Methods). J Basic Microbiol. 1991;31:479–80. [CrossRef]

14. Voytek MA, Ward BB. Detection of ammonium-oxidizing bacteria of the beta-subclass of the class Proteobacteria in aquatic samples with the PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2811. [CrossRef]

15. Shen C-H. Quantification and analysis of proteins. In Shen C-H, ed. Diagnostic Molecular Biology. Academic Press;2023:231-57. [CrossRef]

16. Luang-In V, Yotchaisarn M, Saengha W, Udomwong P, Deeseenthum S, Maneewan K. Protease-producing bacteria from soil in Nasinuan Community Forest, Mahasarakham Province, Thailand. Biomed Pharmacol J. 2019;12:587-95. [CrossRef]

17. Gaete A, Mandakovic D, González M. Isolation and identification of soil bacteria from extreme environments of chile and their plant beneficial characteristics. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1213. [CrossRef]

18. Wery N, Gerike U, Sharman A, Chaudhuri JB, Hough DW, Danson MJ. Use of a packed-column bioreactor for isolation of diverse protease-producing bacteria from Antarctic soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:1457-64. [CrossRef]

19. Masi C, Parthasarathi N. Production and process optimization of protease using various bacterial species-a review. Recent Trends Biotechnol Chem Eng. 2014;6:4268-75.

20. Franco-Duarte R, Cernáková L, Kadam S, Kaushik KS, Salehi B, Bevilacqua A, et al. Advances in chemical and biological methods to identify microorganisms—from past to present. Microorganisms. 2019;7:130. [CrossRef]

21. Alnahdi HS. Isolation and screening of extracellular proteases produced by new Isolated Bacillus sp. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2012;2:2915. [CrossRef]

22. Verma A, Singh H, Anwar MS, Kumar S, Ansari MW, Agrawal S. Production of thermostable organic solvent tolerant keratinolytic protease from Thermoactinomyces sp. RM4: IAA production and plant growth promotion. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1189. [CrossRef]

23. Williams CM, Richter CS, MacKenzie JM, Shih JCH. Isolation, identification, and characterization of a feather-degrading bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1509. [CrossRef]

24. Chen L, Cai Y, Zhou G, Shi X, Su J, Chen G, et al. Rapid sanger sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene for identification of some common pathogens. PLoS One. 2014;9:88886. [CrossRef]

25. He F. Laemmli-SDS-PAGE. Bio-Protocol. 2011;1:e80. [CrossRef]

26. Mazotto AM, Lage Cedrola SM, Lins U, Rosado AS, Silva KT, Chaves JQ, et al. Keratinolytic activity of Bacillus subtilis AMR using human hair. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2010;50:89-96. [CrossRef]

27. Keshapaga UR, Jathoth K, Singh SS, Gogada R, Burgula S. Characterization of high-yield Bacillus subtilis cysteine protease for diverse industrial applications. Braz J Microbiol. 2023;54:739-52. [CrossRef]

28. Marathe SK, Vashistht MA, Prashanth A, Parveen N, Chakraborty S, Nair SS. Isolation, partial purification, biochemical characterization and detergent compatibility of alkaline protease produced by Bacillus subtilis, Alcaligenes faecalis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa obtained from sea water samples. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2018;16:39-46. [CrossRef]