1. INTRODUCTION

India, endowed with rich biodiversity, boasts an array of wild fruits that have been an integral part of traditional diets and folk medicine for centuries. These fruits, sourced from diverse ecosystems across the subcontinent, not only contribute to culinary diversity but also harbor a rich source of bioactive compounds with potential health benefits. Incorporating Indian fruit varieties can have a variety of health benefits, including improved digestive health, heart health (lowering blood pressure and cholesterol), enhanced immunity (vitamin C-rich fruits), skin health, and blood sugar control. Fruits are also a rich source of antioxidants [1]. The exploration of antioxidant-rich fruits aligns with a global paradigm shift toward preventive healthcare and the recognition of dietary interventions as pivotal components of well-being.

Common Indian wild fruits, such as Phyllanthus emblica, Syzygium cumini, Ziziphus mauritiana, Punica granatum, Aegle marmelos, and Annona squamosa, have drawn significant scientific interest due to their rich phytochemical compositions. These fruits are replete with polyphenols, flavonoids, and other bioactive compounds, contributing to their antioxidant potential [2]. Traditional medicinal practices in India have long harnessed the therapeutic properties of these fruits, recognizing their ability to bolster the body’s defense against oxidative stress and associated ailments.

As India generally bears the burden of communicable and noncommunicable diseases, perceiving the antioxidant properties of common Indian wild fruits becomes paramount. This exploration not only sheds light on traditional wisdom but also provides a scientific basis for incorporating these fruits into modern dietary patterns and wellness strategies. In this context, this study aims to delve into the antioxidant properties and anticancer potential of wild cucumber fruit (C. pubescens), unraveling their phytochemical intricacies and potential health implications.

C. pubescens (fruit), colloquially known as the prickly cucumber or gooseberry cucumber, has been regarded as a subject in medicinal plant research. Although usually not cultivated, this plant commonly thrives as a weed amidst other crops. It tends to flourish in fields where sorghum, maize, and groundnut were cultivated, particularly in arid and infertile soils. Its growth is widespread across the drier regions of India. Characterized by a hairy stem, the plant produces yellow flowers, and its fruit skin displays various colors, including yellow, striped green, and brown. It is capturing attention owing to its promising health-promoting properties. Belonging to the Cucurbitaceae family, this fruit has a history of traditional medicinal uses across various cultures [3]. As the demand for natural remedies and functional foods continues to grow, exploring the therapeutic properties of C. pubescens has become essential. The interest in C. pubescens is driven by its composition of bioactive compounds, including polyphenols and flavonoids, known for their potential antioxidants. A variety of antioxidants contribute to reducing oxidative stress and are also associated with different diseases, especially cancer [4]. Oxidative stress happens when there is a disproportion between reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and the body’s capability to reduce their effect, followed by causing cellular damage and contributing to initiation of cancer-related diseases.

The relationship between antioxidant potential and anticancer properties has been discussed in biomedical research using various medicinal plants. Multiple scientific articles explore the interplay between cellular redox balance and carcinogenesis. Antioxidants, by nature, are capable of neutralizing ROS and moderate oxidative stress, play a pivotal role in maintaining cellular homeostasis, and prevent DNA damage [5]. Elevated levels of oxidative stress are characterized by an inequity between the production of ROS and the defense system of antioxidants, and they have been implicated in the initiation and progression of various cancers. Antioxidants, sourced from both endogenous cellular mechanisms and exogenous dietary components, act as frontline defenders against ROS-induced cellular damage. Importantly, the capacity of antioxidants to scavenge free radicals and oxidative stress is reduced. The exploration of their potential is used in cancer prevention and treatment. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that compounds with robust antioxidant potential, such as polyphenols and flavonoids found in various fruits and vegetables, exhibit anticancer activities by interfering with cancer cell proliferation, inducing apoptosis, and suppressing angiogenesis [6]. However, the intricate balance between pro-oxidant and antioxidant effects poses challenges in extrapolating these findings to clinical settings, highlighting the need for a detailed understanding of the role of antioxidants in cancer biology. While antioxidant-rich diets have shown promise in reducing cancer risk, the complex nature of cancer demands a robust approach that considers individual variability, the specific type of cancer, and the stage of its development [7]. Thus, elucidating the dynamic relationship between antioxidant potential and anticancer effects remains a crucial area of research, with implications for both preventive strategies and therapeutic interventions in the study of oncology.

While preliminary investigations hint at the antioxidant potential of C. pubescens, a comprehensive elucidation of its bioactive constituents and their specific modes of action are paramount. This research endeavors to bridge existing knowledge gaps, delving into the molecular intricacies of how C. pubescens may mitigate oxidative stress and, consequently, contribute to the prevention or treatment of diseases, with a particular focus on cancer. By scrutinizing the fruit’s pharmacological attributes, this study seeks to understand the scientific need for the utilization of C. pubescens as a potential therapeutic agent, thus aligning with the global pursuit of effective and sustainable health interventions.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The antioxidant properties of C. pubescens (Fruit) were determined through enzymatic activity assays, including SOD, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase, along with the estimation of redox potential through the DPPH assay. The comparison was done to identify the antioxidant potential between standard and fruit extract. Notably, the C. pubescens fruit extract demonstrated exceptional performance, surpassing the standard in terms of % inhibition in all assays, except for the catalase assay, where it performed well. This observation was consistent across varying concentrations for each respective assay.

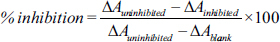

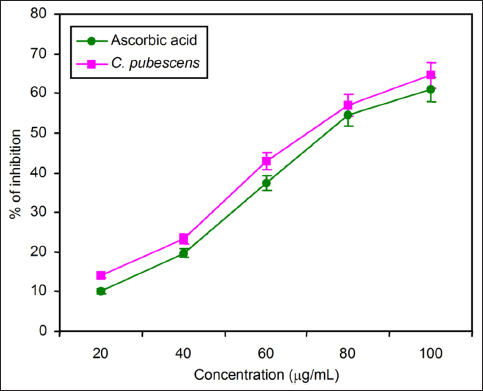

3.1. Superoxide Dismutase

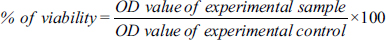

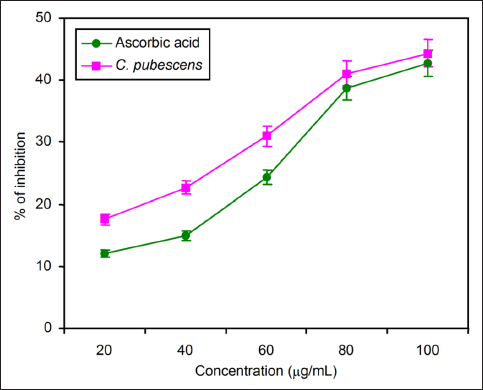

The SOD assay of the C. pubescens fruit extract showed various concentrations from 20 to 100 µg/mL, inferring that the activity increased when the concentration of the fruit extract increased. The results showed a gradual increase in the dosage of fruit extract concentration. The maximum SOD activity was observed in 100 µg/mL and the 44.30 ± 0.24 percentage of inhibition was recorded against the standard ascorbic acid [Figure 1].

| Figure 1: Comparison of the superoxide dismutase activity of standard ascorbic acid and C. pubescens fruit extract at different concentrations. All the values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation with three replicates.

[Click here to view] |

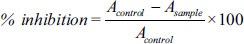

3.2. Catalase

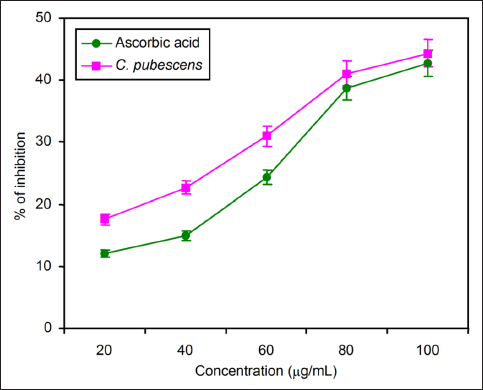

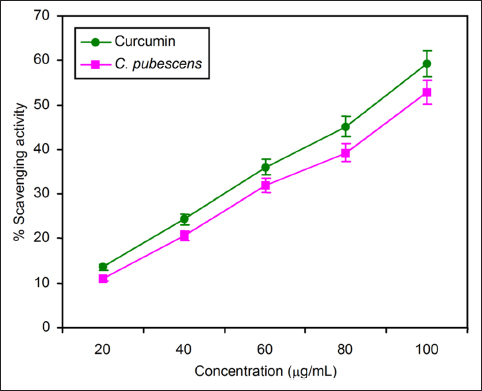

The catalase activity was reduced when the concentration of fruit extract increased. The maximum activity of catalase recorded in standard curcumin is as follows: 13.56 ± 0.64, 24.37 ± 0.23, 36.02 ± 0.46, 45.15 ± 0.71, and 59.24 ± 0.15. But in C. pubescens the catalase activity was reduced, and the percentage of inhibition was 11.03 ± 0.74, 2.62 ± 0.52, 31.89 ± 0.11, 39.22 ± 0.31, and 52.84 ± 0.42, respectively, from the concentration of 20–100 µg/mL of fruit extract [Figure 2].

| Figure 2: Comparison of the catalase activity of standard curcumin and C. pubescens fruit extract at different concentrations. All the values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation with three replicates.

[Click here to view] |

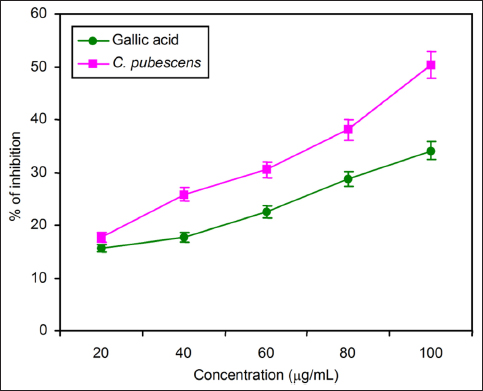

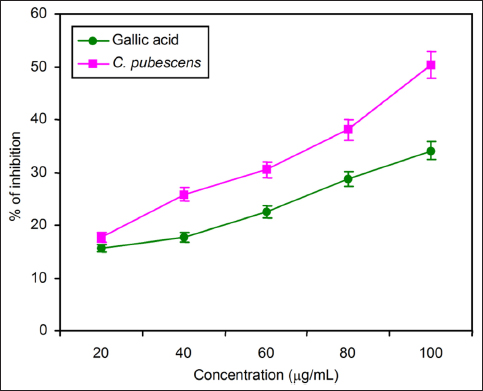

3.3. Glutothione Peroxidase

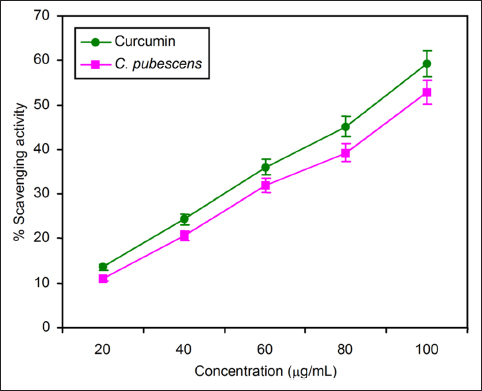

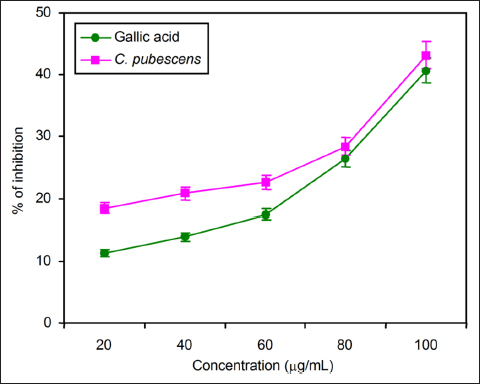

The C. pebescens fruit extract was subjected to glutothione peroxide analysis at the concentrations of 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µg/mL. When compared with the gallic acid used as a standard, the percentage of inhibition was 11.33 ± 0.43, 13.90 ± 0.67, 17.46 ± 0.7, 26.45 ± 0.32, and 40.66 ± 0.26. The fruit extract recorded 18.47 ± 0.43, 20.81 ± 0.68, 22.58 ± 0.22, 28.41 ± 0.85, and 43.18 ± 0.53 as percentages of inhibition. When increasing the concentration of fruit extract, the glutathione peroxidase activities also increased [Figure 3].

| Figure 3: Comparison of glutathione peroxidase activity of standard gallic acid and C. pubescens fruit extract at different concentrations. All the values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation with three replicates.

[Click here to view] |

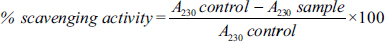

3.4. DPPH

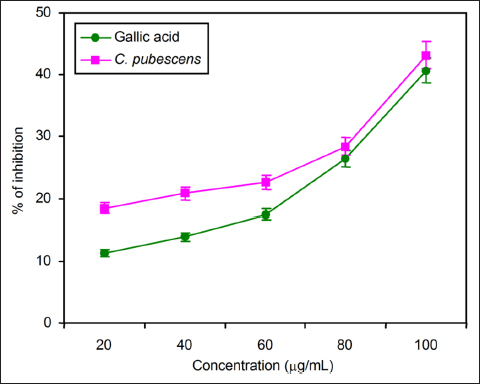

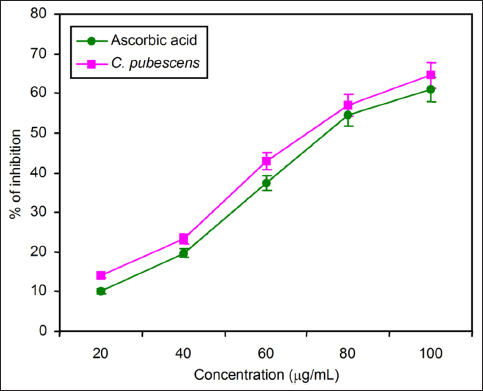

The results of the DPPH (α,α-diphenyl-B-picrylhydrazyl) assay also aligned with the trends observed in other methods for estimating antioxidant properties. The percentage of scavenging activity was shown in 100 µg/mL at its maximum when increasing the concentrations of fruit extract as 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µg/mL. When increasing the concentration of standard ascorbic acid and C. pubescens fruit extract, it increased the DPPH free radical scavenging activity [Figure 4].

| Figure 4: Comparison of redox potential of standard ascorbic acid and C. pubescens fruit extract by DPPH assay at different concentrations. All the values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation with three replicates.

[Click here to view] |

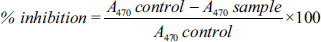

3.5. Glutothione S-Transferase

GST activity was measured by the biochemical method, and MTT assay was carried out by in vitro method. The C. pubescens fruit extract showed better inhibition potential when compared to its standard in GST assay as given in Figure 5. The effect of fruit extract in various concentrations ranging from 20 to 100 µg/mL. The maximum GST activity was recorded at 100 µg/mL, and the lowest percentage of inhibition was recorded at 20 µg/mL of fruit concentration against the standard gallic acid [Figure 5].

| Figure 5: Comparison of glutathione S-transferase activity of standard gallic acid and C. pubescens fruit extract at different concentrations. All the values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation with three replicates.

[Click here to view] |

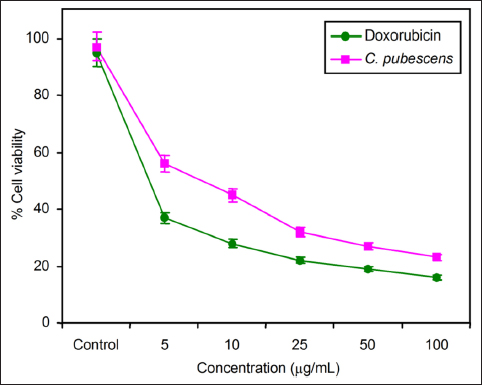

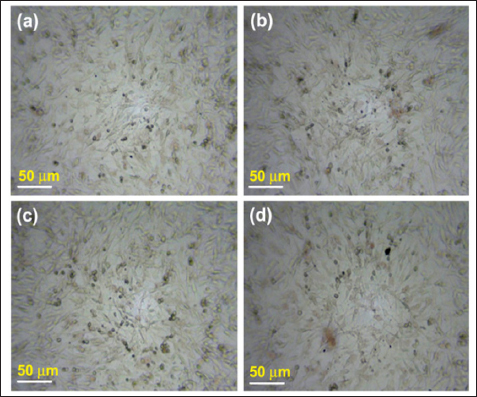

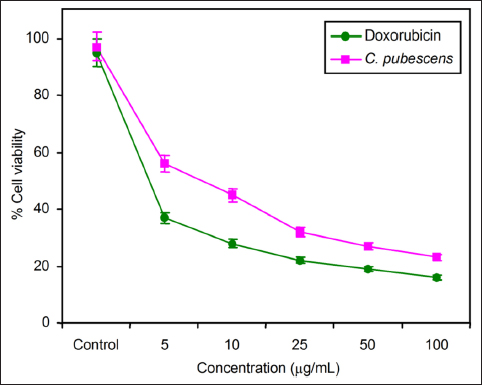

3.6. Cytotoxicity

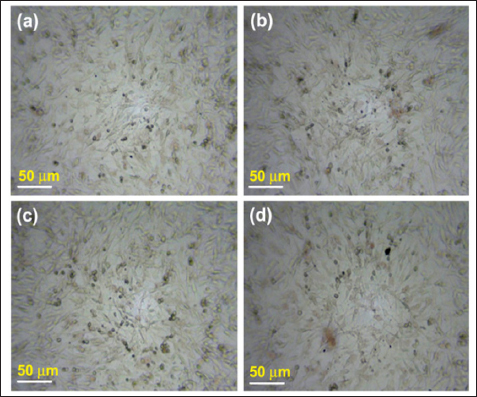

For anticancer potential assessment, both biochemical and in vitro methods were employed. In the in vitro analysis, a comprehensive assessment of cell morphology and cytotoxicity was conducted, with the detailed outcomes presented in Figures 6 and 7, and Table 1. Figure 6 clearly illustrates a dose-dependent response of the cells to the incremental addition of the fruit extract. Notably, the introduction of 50 µg/mL of the fruit extract resulted in a reduction of cells within the defined area compared to the control sample. Moreover, this concentration exhibited enhanced morphological features, showcasing well-defined cells with fairly regular shapes.

| Figure 6: 10× image of bright-field inverted light microscopy of A549 lung cancer cells with varying concentrations of C. pubescens fruit extract. (a) Control, (b) 10 µg/mL, (c) 25 µg/mL, and (d) 50 µg/mL.

[Click here to view] |

| Figure 7: Comparison of cell viability between C. pubescens fruit extract and doxorubicin (positive control) by MTT cell cytotoxicity assay.

[Click here to view] |

Table 1: Experimental results of cell viability analysis by MTT assay.

| Concentration (µg/mL) | Cucumis pubescens Fruit Extract % of Cell Viability | Doxorubicin Positive Control % of Cell Viability |

|---|

| 0 | 97 | 95 |

| 20 | 56 | 37 |

| 40 | 45 | 28 |

| 60 | 32 | 22 |

| 80 | 27 | 19 |

| 100 | 23 | 16 |

3.7. Cell Viability

The concentration-dependent impact on cell viability is evident in Figure 7, where an increase in the fruit extract concentration from 0 to 100 µg/mL is associated with a gradual decrease in cell viability. These findings are further elucidated and organized in Table 1, providing a comprehensive overview of the observed effects on cell morphology and viability in response to varying concentrations of the fruit extract. Table 2 shows that the IC50 value of the fruit extract was estimated to be 7.5 ± 1.5, in comparison to doxorubicin, employed as a positive control, which demonstrated an IC50 of 6 ± 0.5 over a 24-h time period.

Table 2: IC50 estimation by MTT assay.

| Sample Name | IC50 (µg/mL) |

|---|

| C. pubescens fruit extract | 7.5 ± 1.5 |

| Doxorubicin | 6 ± 0.5 |

C. pubescens, an Indian wild plant variety, has been relatively underexplored in prior research, resulting in limited available resources on its characteristics, uses, and potential medicinal benefits. While the existing literature is sparse, some sources suggest a synonymous relationship between C. pubescens and C. melo, the widely cultivated honeydew melon in India [17]. This relationship allows for meaningful comparisons to be drawn not only between these two distinct species but also with other members of the Cucumis genera. Exploring such associations provides a valuable foundation for understanding the unique features and potential applications of C. pubescens within the broader context of its plant family.

An extensive array of resources exist for comprehending the therapeutic potential of C. melo globally. Researchers in the study of food and pharmaceuticals have examined plant extracts from diverse parts of the C. melo plant, seeking therapeutic molecules and elucidating its potential mechanisms of action. Notably, investigations have highlighted the antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic properties inherent in the seeds of C. melo [18]. Traditional uses have attributed to its diuretic properties. The plant has garnered significant attention for its antioxidant potential, as evidenced by numerous studies [19]. In contrast, C. pubescens remains relatively unexplored, presenting a compelling avenue for exploration. It holds the potential to yield health benefits equal to or even surpassing those found in cultivated honeydew melons. Hence, a comprehensive investigation into C. pubescens is of paramount importance to understand its untapped therapeutic potential and contribute to our understanding of its health-promoting properties.

This investigation assessed both the antioxidant properties and anticancer potential of C. pubescens through a series of gauging tests. Given the straightforward nature of studying SOD as an enzyme for comprehending antioxidant potential, it is noteworthy that prior research has already established C. melo as a notable source of SOD enzyme [20]. Several common enzymes utilized to assess antioxidant potential include SOD, catalase, GPx, ascorbate peroxidase, ascorbate oxidase, guaiacol peroxidase, and glutathione reductase. Additionally, nonenzymatic methods, such as measurement of DPPH reduction, total phenolic content, flavonoids, saponins, ascorbic acids, anthocyanins, FRAP, and ABTS, constitute a diverse array of techniques available for comprehending antioxidant potential. It is not mandatory to employ all methods to establish the antioxidant properties of a sample. Simultaneously, not all methods measure similar substrates to elucidate antioxidant properties. Therefore, the choice of methods depends on the researcher’s discretion, laboratory capabilities, and the feasibility of conducting a specific assay to determine the antioxidant properties of a test substance. Being a wild variety rather than a cultivated one, C. pubescens exhibits a higher tolerance to both drought and salinity. Previous studies have identified the abundance of antioxidant enzymes, including SOD, catalase, and ascorbate peroxidase, in salinity-tolerant varieties of C. melo [21]. We possess substantial evidence indicating a correlation between antioxidant properties and the potential for anticancer effects. While cancer employs various mechanisms to invade normal cells, these mechanisms ultimately lead to the generation of free radicals. A robust antioxidant has the capacity to mitigate the damage caused by free radicals to a considerable extent, potentially counteracting the harmful effects of cancer cells [22]. The inherent qualities observed in C. pubescens make it a compelling candidate for further exploration in evaluating its potential anticancer properties. Similar results were reported for Limonia elephantum, which is commonly known as wood apple in Indian folk medicine [23,24].

The assessment of anticancer potential encompassed both biochemical and in vitro methods, with the evaluation of GST activity constituting the biochemical approach, while the MTT assay served as an in vitro method. Within the Cucumis genus, one noteworthy compound of interest is cucurbitacin, a secondary metabolite prevalent in the Cucurbitaceae family. Extensively studied for its anti-inflammatory properties, antitumor effects, and antidiabetic activity, cucurbitacin holds promise for various therapeutic applications [25]. It is important to note that the current study does not focus on isolating specific molecules responsible for anticancer properties. Instead, the objective is to utilize the crude extract of the whole fruit to explore potential therapeutic benefits.

The presence of GST in cucumber varieties has been documented, particularly in response to cold stress in plants [26]. This enzyme is involved in one of the most prevalent pathways crucial for the plant’s detoxification response, potentially playing a significant role in mitigating the impact of carcinogenic cells. Another mechanism under consideration involves the efficient elimination of xenobiotic substances post their interaction with GST. These mechanisms collectively highlight the multifaceted role of GST in contributing to the detoxification processes within cucumber varieties. The fruit extract also possesses neuroprotective activity in vivo using rat models [27].

Cell cytotoxicity assays conducted on cancer cell lines serve as a crucial method for assessing the potential anticancer activity of the molecules or extracts under investigation. Numerous studies have explored the anticancer effects of various Indian fruits, employing cancer cell lines such as A549, HepG2, MDA-MB-231, among others [28,29]. Remarkably, some of the most effective anticancer drugs have been derived from common Indian fruits and vegetables. This underscores the significance of investigating natural sources for potential therapeutic agents in the fight against cancer. Cucurbitacins elicit arrest of cell growth and induce apoptosis in a diversity of cancer cells. This action occurs through the suppression of Akt phosphorylation, subsequently leading to the modulation of p21/cyclin signal, activation of mitochondria-dominated caspase pathways, and interference with signaling pathways associated with the migration of cancer cells and invasion [30,31]. Moringa concanensis is active against anticancer properties by using HepG2 cell lines. The plant is reported to be a novel and natural phytomedicine against various diseases [32]. Nevertheless, a comprehensive study is essential for the isolation and characterization of the specific molecules responsible for the anticancer effects observed in C. pubescens fruits. This necessitates the utilization of robust and systematic methods, including in vivo studies, to firmly establish the research findings. Such an investigation holds the potential to create a market for this fruit, paving the way for the utilization of naturally derived substances for medical purposes.

REFERENCES

1. Sharifi-Rad M, Anil Kumar NV, Zucca P, Varoni EM, Dini L, Panzarini E, et al. Lifestyle, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: back and forth in the pathophysiology of chronic diseases. Front Physiol. 2020;11:694. [CrossRef]

2. Sidhu J, Zafar T. Fruits of the Indian subcontinent and their health benefits. In: Sen S, Chakraborty R, editors. Her Med India. Singapore: Springer; 2020. p. 451–78.

3. Mukherjee PK, Nema NK, Maity N, Sarkar BK. Phytochemical and therapeutic potential of cucumber. Fitoterapia. 2013;84:227–36. [CrossRef]

4. Insanu M, Rizaldy D, Silviani V, Fidrianny I. Chemical compounds and pharmacological activities of Cucumis genus. Biointerface Res App Chem. 2022;12(1):1324–34.

5. Pizzino G, Irrera N, Cucinotta M, Pallio G, Mannino F, Arcoraci V, et al. Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:8416763. [CrossRef]

6. Ullah A, Munir S, Badshah SL, Khan N, Ghani L, Poulson BG, et al. Important flavonoids and their role as a therapeutic agent. Molecules. 2020;25(22):5243. [CrossRef]

7. Aghajanpour M, Nazer MR, Obeidavi Z, Akbari M, Ezati P, Kor NM. Functional foods and their role in cancer prevention and health promotion: a comprehensive review. Am J Cancer Res. 2017;7(4):740–69. PMID: 28469951

8. Gamble JS. Flora of the presidency of madras. Calcutta: Botanical Survey of India; 1935.

9. Henry AN, Kumari GR. Chitra V. Flora of Tamil Nadu India. Series 1: Analysis. Vol. 2. Coimbatore: Botanical Survey of India; 1987.

10. Lester GE, Hodges DM, Meyer RD, Munro KD. Pre-extraction preparation (fresh, frozen, freeze-dried, or acetone powdered) and long-term storage of fruit and vegetable tissues: effects on antioxidant enzyme activity. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52(8):2167–73. [CrossRef]

11. Lester GE, Jifon JL, Crosby KM. Superoxide dismutase activity in mesocarp tissue from divergent Cucumis melo L. genotypes. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2009;64(3):205–11. [CrossRef]

12. Haida Z, Hakiman M. A comprehensive review on the determination of enzymatic assay and nonenzymatic antioxidant activities. Food Sci Nutr. 2019;7(5):1555–63. [CrossRef]

13. Gnanamangai BM, Saranya S, Ponmurugan P, Kavitha S, Pitchaimuthu S, Divya P. Analysis of antioxidants and nutritional assessment of date palm fruits. In: Naushad M, Lichtfouse E, editors. Sustainable Agriculture Reviews. Vol. 34. Cham: Springer. 2019; p. 19–40.

14. Gokçe B. Some anticancer agents as effective glutathione S-transferase (GST) inhibitors. Open Chem. 2023;21(1):20230159.

15. Lee SH, Jaganath IB, Wang SM, Sekaran SD. Antimetastatic effects of Phyllanthus on human lung (A549) and breast (MCF-7) cancer cell lines. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20994. [CrossRef]

16. Farshori NN, Al-Sheddi ES, Al-Oqail MM, Musarrat J, Al-Khedhairy AA, Siddiqui MA. Cytotoxicity assessments of Portulaca oleracea and Petroselinum sativum seed extracts on human hepatocellular carcinoma cells (HepG2). Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(16):6633–8. [CrossRef]

17. Renner SS, Pandey AK. The Cucurbitaceae of India: accepted names, synonyms, geographic distribution, and information on images and DNA sequences. PhytoKeys. 2013;(20):53–118. [CrossRef]

18. Gill NS, Bajwa J, Dhiman K, Sharma P, Sood S, Sharma PD, et al. Evaluation of therapeutic potential of traditionally consumed Cucumis melo seeds. Asian J Plant Sci. 2011;10:86–91.

19. Asif HM, Rehman SU, Akram M, Akhtar N, Sultana S, Rehman JU. Medicinal properties of Cucumis melo Linn. J Pharm Pharma Sci. 2014;2(1):58–62.

20. Vouldoukis I, Lacan D, Kamate C, Coste P, Calenda A, Mazier D, et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of a Cucumis melo LC. extract rich in superoxide dismutase activity. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;94(1):67–75. [CrossRef]

21. Furtana GB, Tipirdamas R. Physiological and antioxidant response of three cultivars of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) to salinity. Tur J Biol. 2010;34(3):8.

22. Liaudanskas M, Žvikas V, Petrikaite V. The potential of dietary antioxidants from a series of plant extracts as anticancer agents against melanoma, glioblastoma, and breast cancer. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021;10(7):1115. [CrossRef]

23. Kamalakkannan K, Balakrishnan V. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective activity of ethanolic and aqueous extracts of Limonia elephantum corr. Leaves. Ban J Pharma. 2014;9:383–8.

24. Kamalakkannan K, Balakrishnan V. Hypoglycemic activity of aqueous leaf extract of Limonia elephantum Corr.in normal and alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Ban J Pharma. 2014;9:443–6.

25. Kaushik U, Aeri V, Mir SR. Cucurbitacins - an insight into medicinal leads from nature. Pharmacogn Rev. 2015;9(17):12–8. [CrossRef]

26. Duan X, Yu X, Wang Y, Fu W, Cao R, Yang L, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of glutathione S-transferase gene family to reveal their role in cold stress response in cucumber. Front Genet. 2022;13:1009883. [CrossRef]

27. Kumar H, Sharma S, Vasudeva N. Evaluation of nephroprotective and antioxidant potential of Cucumis pubescens in rats. J Med Pharma Alli Sci. 2021;10(5):3517–20.

28. Hanif A, Ibrahim AH, Ismail S, Al-Rawi SS, Ahmad JN, Hameed M, et al. Cytotoxicity against A549 human lung cancer cell line via the mitochondrial membrane potential and nuclear condensation effects of Nepeta paulsenii Briq., a perennial herb. Molecules. 2023;28(6):2812. [CrossRef]

29. Garg M, Lata K, Satija S. Cytotoxic potential of few Indian fruit peels through 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay on HepG2 cells. Indian J Pharmacol. 2016;48(1):64–8. [CrossRef]

30. Kalebar VU, Hoskeri JH, Hiremath SV. In-vitro cytotoxic effects of Solanum macranthum fruit. Dunal extract with antioxidant potential. Clin Phytosci. 2020;6:24.

31. Wu D, Wang Z, Lin M, Shang Y, Wang F, Zhou J, et al. In Vitro and In Vivo antitumor activity of Cucurbitacin C, a novel natural product from cucumber. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1287. [CrossRef]

32. Balamurugan V, Balakrishnan V, Philip Robinson J, Ramakrishnan M. Anticancer and apoptosis-inducing effects of Moringa concanensis using HepG-2 cell lines. Ban J Pharm 2014; 9 (4) 604-609.